* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Patrick Wright. Iron Curtain: From Stage to Cold War. New York

Western betrayal wikipedia , lookup

1960 U-2 incident wikipedia , lookup

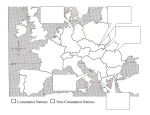

Containment wikipedia , lookup

Consequences of Nazism wikipedia , lookup

Origins of the Cold War wikipedia , lookup

Cuba–Soviet Union relations wikipedia , lookup

Aftermath of World War II wikipedia , lookup

Operation Anadyr wikipedia , lookup

Cold War (1962–1979) wikipedia , lookup

Cold War (1947–1953) wikipedia , lookup

Cold War (1953–1962) wikipedia , lookup

1130 Reviews of Books emphasizes the post-Stalin Soviet leaders’ preoccupation with sorting out their own power positions and dealing with the serious repercussions of Stalin’s domestic Cold War of purges, xenophobic isolationism, and antisemitism (pp. 50–61). On the critical issue of whether or not Moscow would have accepted a united, neutral Germany, Zubok depicts Soviet diplomatic demarches from the Kremlin in 1953–1955 as maneuvers to hinder U.S. plans to integrate West Germany into the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) rather than as a meaningful attempt to negotiate a compromise. Leffler illuminates well the multiple pressures and spreading global competition that worked against a lasting détente. In his review of Khrushchev and Kennedy’s negotiations of a limited nuclear test ban, Leffler emphasizes that the constraints on both sides were very substantial (pp. 187–201). Zubok offers a more critical perspective on Khrushchev than Timothy Naftali and Aleksandr Fursenko in their recent study, Khrushchev’s Cold War: The Inside Story of an American Adversary (2006). Zubok rejects their thesis that Khrushchev had a grand strategy for détente. Instead, he suggests that Khrushchev’s reliance on “nuclear brinkmanship was exceptionally crude and aggressive, reckless and ideology-driven” and that he “relied more on his instincts than on strategic calculations” as “his ideological beliefs, coupled with his emotional vacillations between insecurity and overconfidence, made him a failure as a negotiator (pp. 153, 338). There was little room for more than limited agreements, as Khrushchev stepped up competition in the Middle East, Africa, and Cuba, and Washington more than matched the Kremlin in these areas and the conflict in Vietnam escalated. Leffler and Zubok highlight the efforts of Carter and Brezhnev to continue détente after 1976, even though it had been fatally weakened by actions and inactions on both sides, as well as by the decline of Brezhnev’s health after 1972 and his gradual loss of control of Soviet policy and initiatives. Nevertheless, Leffler points out Carter’s persistent effort to keep détente alive with Brezhnev, and Zubok emphasizes Brezhnev’s efforts to maintain détente in order to avoid the risks of war that Khrushchev had encouraged. In relying extensively on memoirs by and interviews with Brezhnev’s advisers, Zubok minimizes the overall destructive impact of the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968 on both détente and on the Soviet Union’s relationship with Eastern Europe. Furthermore, the Kremlin’s offensive in Africa was at least as unsuccessful in exporting its model of socialist modernization as the United States was in exporting democratic capitalism, a point that is convincingly demonstrated in Odd Arne Westad’s The Global Cold War: Third World Interventions and the Making of Our Times (2005). In their assessments of Reagan and Gorbachev and the end of the Cold War, Leffler and Zubok reaffirm their central consensus on the nature of the conflict, why it lasted as long as it did, and why it ended the way it did. Both authors give significant credit to Reagan, AMERICAN HISTORICAL REVIEW but not to his revitalized containment strategy. Instead, they emphasize the importance of Reagan’s willingness to negotiate with Soviet leaders, especially Gorbachev, and to reassure him that the U.S. did not threaten Soviet security and was prepared to negotiate on most arms control issues (Leffler, pp. 449– 450, 462– 466; Zubok, pp. 285–289, 343). Leffler and Zubok also assign to Gorbachev primary credit for making the most significant changes concerning Soviet ideological preconceptions, views of international relations, and policy orientation toward external involvements from Central America to Afghanistan. In effect, Gorbachev abandoned the “struggle for the soul of mankind” that the authors emphasize as the core of the Cold War conflict. Leffler and Zubok give different emphases to the final stage of the conflict, the collapse of the Soviet empire, and the Soviet Union itself. Gorbachev is Leffler’s favorite Soviet leader, and he approves of Gorbachev’s unwillingness to defend communist regimes in Eastern Europe, including East Germany. Zubok, however, criticizes Gorbachev for replacing the revolutionaryimperial paradigm with “new thinking,” a radical transformation of Soviet ideology and political and economic systems, which included opening the country to the West and the world. Zubok would have preferred a cautious, gradualist approach based on a systematic strategy that insisted on negotiations and concessions from the West for major Soviet actions, such as agreeing to the unification of Germany within NATO. In short, Zubok endorses Stalin and Brezhnev as superior strategists and negotiators over Khrushchev and Gorbachev. THOMAS R. MADDUX California State University, Northridge PATRICK WRIGHT. Iron Curtain: From Stage to Cold War. New York: Oxford University Press. 2007. Pp. xvi, 488. $34.95. It is rare to find a historian willing to explore, in any systematic way, the relationship between politics and language. After all, the popularity of political history owes much to the easy complicity with which we accept the conventional modes of human communication, leaving terminological issues to the philosophers, or to occasional scolds like George Orwell. But Orwell is long gone and the philosophers today seem rather disinterested. Individual words often carry a lot of dangerous freight. Mischievous hybrids (“Islamo-fascism” would surely be one current example) flourish provocatively in the media. And academic as well as public discourse is littered with emotion-laden images and truth-obscuring metaphors. All credit then to Patrick Wright for inquiring into the origins of the “iron curtain,” a ubiquitous metaphor of the Cold War era. The term is indelibly associated with Winston Churchill, who made it the central image of his famous speech at Westminster College in Fulton, Missouri, on March 5, 1946, sounding the alarm about OCTOBER 2008 Comparative/World Soviet postwar expansionist ambitions in and around Europe. Churchill was perfectly happy to leave undisturbed the general impression that this was yet another of his imaginative coinages. Actually, Joseph Goebbels, similarly drawing attention to the Soviet threat, had used the phrase earlier in 1944. Now Wright takes us further back to the aptly named “iron curtain” devised in the nineteenth century to provide some metallic security against the many deadly infernos caused in London theaters by the use of candles, oil lamps, lighted chandeliers, and highly inflammable special effects, including fireworks. The iron curtain protected the audience, if not the less-enraptured actors and stage hands on the other side. The transition to political imagery was made, appropriately, by the playwright and pacifist/internationalist Vernon Lee. Shocked by the advent and experience of world war in 1914, she lamented “the moment when war’s cruelties and recrimination, war’s monstrous iron curtain, cut us off so utterly from one another” (p. 80). A variety of references to the “iron curtain” surfaced during the turbulent 1914 –1920 period, although it seems not to have become a stock phrase. Internationalists in Lee’s circle used it to express their anguish over the breakdown of European civilization. Queen Elisabeth of the Belgians employed it in 1915 to condemn the high tension electricity wires with which the occupying Germans closed the Belgo-Dutch frontier. A postwar French prime minister warned against “lowering an iron curtain on the frontier of unoccupied Germany” (p. 222). It fell to the British leftist Ethel Snowden— who, upon her arrival in the postwar Soviet state as part of a supportive delegation, noted “We were behind the iron curtain at last” (p. 152)—to pioneer the henceforth more exclusive focus of the image upon the Red specter. However, despite a good deal of venomous East/West imagery in the interwar years, actual references to the “iron curtain” appear to have been rare and, as Wright acknowledges, “the phrase fell into comparative disuse during the 1930s.” In the end then, although this book is very well written, interesting, and full of stimulating digressions, the results of the quest, insofar as it relates to the metallic phrase itself, are rather thin. One senses a certain unacknowledged disappointment in the author, who begins, as the small well of quotable usages dries up after World War I, to use the phrase to describe various political tensions and ruptures in interwar Europe, especially with regard to the Soviet Union. The assumption seems to be that if people were not using this particular metaphor, they were nonetheless thinking along the lines it had been coined to suggest. But that is not quite the same thing, and the constant reiteration of the phrase leads to a confused thesis. One cannot help but wish that Wright, once he saw the limits of a subject confined in this way to the odyssey of a single phrase, had adopted a different strategy focusing not, as is the case here, on the many misguided pilgrims to the new socialist state (whose illusions have been exhaustively unmasked by many unsympathetic AMERICAN HISTORICAL REVIEW 1131 writers). Instead, he might have focused on the iron curtain, not as an exclusive mental construct but as one of a number of similarly striking, strongly suggestive, and surely related metaphors that have been devised repeatedly and with profound effect since 1914 to serve particular interests and to shape public responses to the tensions and divisions of European power politics. The “cordon sanitaire” is one obvious example of a similar image that could have been creatively linked (it receives only a brief treatment here) with the “iron curtain,” which in its familiar Churchillian form was perhaps its lineal descendant, and one that then led in its turn to the enduring “containment” images of the mature Cold War. That would be a subject worthy of the literary and forensic talents impressively on display here. FRASER J. HARBUTT Emory University MICHAEL CRESWELL. A Question of Balance: How France and the United States Created Cold War Europe. (Harvard Historical Studies, number 153.) Cambridge: Harvard University Press. 2006. Pp. xvi, 238. $49.95. In the crucial year 1950, Western powers were on the defensive in the global context of the Cold War. A communist government had gained control of mainland China. France found itself bogged down in a colonial war in Indochina. The Korean War erupted, stretching thin the resources of the United States. And, despite the signing of the NATO alliance the year before, Western Europe’s security seemed precarious in the face of substantial Soviet conventional forces in Eastern Europe. To further strengthen the defense of Western Europe, given French colonial preoccupations and the U.S.-led engagement in Korea, the Truman administration decided that West Germany, now rebuilding its industrial economy, would need to be rearmed. There were risks involved. The Soviets would oppose; the British would consent; but would the French be willing to have Germans in uniform five years after the defeat of the Nazi regime? An older historical narrative has France accepting German rearmament reluctantly and only as the result of high-handed pressure from the United States—a French Caliban yielding to the material might of an American Prospero. Recent scholarship has challenged this story of American omnipotence and French dependency. The revision argues that the United States did not always get what it wanted from the French, despite the weaknesses of the Fourth Republic and the asymmetrical power relationship between the two countries. Michael Creswell’s extensively researched monograph makes a significant contribution to this revisionist trend and carries the assessment of France’s role in the Cold War a step further by arguing that French statesmen feared the Soviet threat to French security more than they dreaded a revived German militarism. The same statesmen understood, however, the psychology of the French electorate. Germany was the historical enemy and thus the Soviet Union, at least for a sub- OCTOBER 2008