* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download View/Open - MARS - George Mason University

Roman army of the late Republic wikipedia , lookup

Alpine regiments of the Roman army wikipedia , lookup

Food and dining in the Roman Empire wikipedia , lookup

Education in ancient Rome wikipedia , lookup

Promagistrate wikipedia , lookup

Switzerland in the Roman era wikipedia , lookup

Romanization of Hispania wikipedia , lookup

Roman funerary practices wikipedia , lookup

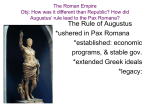

Constitutional reforms of Augustus wikipedia , lookup

Roman economy wikipedia , lookup

Demography of the Roman Empire wikipedia , lookup

Early Roman army wikipedia , lookup

Culture of ancient Rome wikipedia , lookup

History of the Constitution of the Roman Empire wikipedia , lookup

Roman agriculture wikipedia , lookup