* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

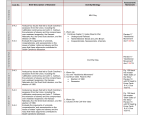

Download Three Southwest Georgia Counties during the Secession Crisis

Missouri secession wikipedia , lookup

Alabama in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Origins of the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Virginia in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Union (American Civil War) wikipedia , lookup

Border states (American Civil War) wikipedia , lookup

Mississippi in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Tennessee in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Secession in the United States wikipedia , lookup

South Carolina in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Issues of the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

United States presidential election, 1860 wikipedia , lookup