* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download EFFECTS OF PROOFREADING ON SPELLING

German orthography reform of 1996 wikipedia , lookup

Scripps National Spelling Bee wikipedia , lookup

Spelling of Shakespeare's name wikipedia , lookup

Spelling reform wikipedia , lookup

English orthography wikipedia , lookup

English-language spelling reform wikipedia , lookup

American and British English spelling differences wikipedia , lookup

Journal of Reading Behavior

1992, Volume XXIV, No. 4

EFFECTS OF PROOFREADING ON SPELLING:

HOW READING MISSPELLED AND CORRECTLY SPELLED

WORDS AFFECTS SPELLING ACCURACY

John M. Bradley

University of Arizona

Priscilla Vacca King

Mammoth-San Manuel School District

ABSTRACT

The effects of proofreading on the spelling accuracy of fifth-grade students were

studied by having them read and detect errors in text containing misspelled words.

The treatment involved an error detection task requiring a decision as to whether

an underlined stimulus word embedded in a sentence was correctly spelled or

misspelled. Serving as their own controls, the students were exposed to three

spelling exposure frequency conditions during the proofreading treatment: (a) four

exposures to a misspelling, (b) two exposures to a misspelling and two exposures

to the correct spelling, and (c) four exposures to the correct spelling. The students

proofread two types of spelling words in terms of sound-spelling correspondence;

half were predictable and half were unpredictable. The major finding was that

exposure to correctly spelled words did improve spelling accuracy for immediate

and delayed posttests. Exposure to misspelled words did not significantly affect

the spelling accuracy of the sample as a whole, but the accuracy of a few outliers

was substantially impaired. Unpredictable words were found more difficult to spell

than predictable words. No interaction was found between spelling ability and

spelling accuracy improvement as the result of proofreading correctly spelled

words; poor spellers improved as much as average and good spellers.

Goodman (1984) has suggested that people read texts for a variety of purposes,

and that with the exception of some forms of ritualistic reading, all forms of reading

involve an attempt by the reader to make sense of the text. Proofreading is a form

of reading that is typically associated with either the revision process of writing or

spelling assessment and instruction. Although proofreading for spelling errors in a

413

Downloaded from jlr.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on May 11, 2016

414

. Journal of Reading Behavior

text is a special type of reading with a relatively specific purpose, it shares with

other forms of reading the necessity of text comprehension.

When proofreading is done as part of the writing revision process, the proofreader reads a preliminary draft of a text to identify and correct errors of spelling,

punctuation, and syntax so that the text may be amended into a final draft suitable

for the writer's intended audience (Calkins, 1986; Graves, 1983). Proofreading

may also be done as a part of formal spelling assessment and basal spelling instruction (Wilde, 1992).

The widespread use of standardized tests in state assessment programs has

pressured many teachers to prepare their students for assessment by teaching directly to the tests (Shepard, 1991). Because of the perceived necessity for this

preparation, the contents and formats of the tests can shape instruction (National

Commission on Testing and Public Policy, 1990). Since standardized achievement

tests typically assess spelling with error detection items, many teachers feel compelled to have their students engage in practice exercises identifying deliberately

misspelled words embedded in sentences or word lists (Smith, 1989; Wilde, 1992).

Test publishers also advise teachers to prepare their students for the assessment

process. For example, the teacher's guide for the Iowa Test of Basic Skills contains

the following suggestion: "Develop sensitivity to spelling errors. Give pupils practice in proofreading their own and other written work, lists of words, and printed

or typed words misspelled in context" (Hieronymus, Hoover, & Lindquist, 1988,

p. 55).

Students may also be required to engage in proofreading tasks as a part of

formal spelling instruction. A survey of five spelling programs [Basic Goals in

Spelling (Kottmeyer & Claus, 1980), HBJ Spelling (Madden & Carlson, 1963),

Macmillan Spelling Series (Smith, 1983), The World of Spelling (Thomas, Thomas,

& Lutkus, 1978), and Spelling (Valmont & Valmont, 1980)] indicated that proofreading activities required the detection of misspellings in both lists of words and

sentences. Wilde (1992) has also reported that most basal spelling programs include

proofreading exercises and has condemned their use because these exercises require

students to detect artificial misspellings, a visual memory task that Wilde contended

is likely to contribute to subsequent student spelling confusion.

Proofreading activities have also been found to be commonly used by special

education teachers as a part of their spelling instruction. A survey study by

Vallecorsa, Zigmond, and Henderson (1985) reported regular use of proofreading

activities by 74% of the special education teachers who responded.

Although there is a dearth of research on proofreading as a practice to improve

spelling accuracy, several studies have supported its usefulness as a means of

studying the reading process. Supramanian (1983) investigated proofreading as a

measure of reading ability with British primary-grade students. He had good and

poor readers read two passages of varying difficulty and circle embedded misspellings. Supramanian employed misspellings in his experimental proofreading task

Downloaded from jlr.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on May 11, 2016

Effects of Proofreading

415

that had been detected successfully by both the poor and good readers on a prior

proofreading-type spelling test. He found that the proofreading task differentiated

good and poor readers and concluded that " . . . proofreading ability is a function

of the degree of exposure to the correct forms of misspelled words" (Supramanian,

1983, p. 77). Niemi and Virjamo (1986) investigated differences in the reading of

function and content words by having Finnish university students circle misspelled

words embedded in an expository passage. The misspelled words differed from

their correct versions by the substitution of a single letter. The Finnish language

was used to make it possible to compare function and content words while simultaneously controlling word length and frequency, a phenomenon not possible in

English. Niemi and Virjamo found that misspellings were most difficult to detect

in short function words and long content words.

Research has also been conducted regarding the validity of a proofreading

format for formal spelling assessment. Because proofreading or error recognition

items are used in most standardized spelling tests (Shores & Yee, 1973), several

investigators have examined the relationship between multiple-choice proofreading

spelling tests and their dictation counterparts involving written spellings as responses. Allen and Ager (1965) found factor analytic evidence suggesting that

spelling ability is a unitary skill and reported high intercorrelations among four

methods of testing spelling, one of which was proofreading. Allred (1984), comparing a proofreading spelling test with a dictation spelling test, reported correlations

ranging from .63 to .85. He also found that the proofreading recognition test was

easier for younger students than the written dictation test, but that the difference

between students' abilities to recognize misspellings and produce correct spellings

decreased with age.

There are two commonly advocated applications of proofreading for instructional purposes; proofreading as part of an editing process to improve writing, or

proofreading to scan for misspellings as a means of increasing spelling knowledge.

Personke and Knight (1967) observed that spelling errors in written compositions

may be left uncorrected by students because they lack motivation to proofread their

work, lack time to make corrections, and lack skills needed to locate correct spellings in the dictionary. They found that some students can reduce the incidence of

spelling error in written work if given instruction on proofreading, and they suggested that it may be helpful for students to practice proofreading skills.

Despite the evidence that editing for spelling accuracy is a useful part of the

writing process, effective writing also depends in part on prior knowledge of correct

spellings. Prior spelling knowledge allows the writing process to continue without

interruptions to ascertain correct spellings. To that end, spelling is taught as an

independent subject, and proofreading exercises are often presented as a means of

increasing spelling knowledge.

Although proofreading has been ignored in some scholarly reviews of spelling

instruction practices, it has been favorably regarded when considered. Graham and

Downloaded from jlr.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on May 11, 2016

416

Journal of Reading Behavior

Miller (1979) listed proofreading among spelling instruction practices supported by

research, and recommended specific activities such as having students identify

incorrect spellings in short lists of words and asking students to search for misspellings in compositions. The authors checked the articles cited by Graham and Miller

in support of their proofreading suggestions and found that the research-based

papers tended to be methodologically unsound, whereas the others were wisdom

pieces.

Some research has suggested that proofreading activities may not increase

spelling knowledge and may even interfere with accurate spelling. Caisley (1982)

incorporated weekly proofreading exercises into the spelling curriculum of students

in Grades K through 7 in one school in Canada. She found that students in the

proofreading program did no better on a recognition spelling test than control group

students, whereas their performance was worse on a dictated written spelling test.

However, Caisley reported that her findings were less conclusive for the poorer

spellers in her sample who improved their scores somewhat on the recognition

spelling test. Jacoby (1983) used an error detection task to study recall processes

and observed that spelling response time was speeded or slowed depending on

whether a recently read word was spelled correctly or incorrectly. He also found

that viewing a correctly spelled word increased the probability of a subsequent

correct spelling of the word on a posttest, whereas viewing an incorrectly spelled

word increased the probability of a misspelling.

Brown (1988) conducted three investigations of the effects of exposure to

misspellings on subsequent spelling performance of undergraduate college students.

Brown limited the data analysis in his three studies to decrement scores only; he

did not investigate the possibility of spelling improvement related to exposure to

correct spellings. In the first study, Brown found that a treatment involving student

generated misspellings for a list of words spelled correctly on a pretest resulted in

an increased number of spelling errors on a posttesting of those words. In the

second study, Brown exposed his student participants to two different misspellings

for each word in a spelling list, had them rate how closely the misspellings resembled the correct versions, and then gave them either a dictated test or a proofreading

recognition test of the listed words. Brown found that exposure to presented misspellings adversely affected spelling accuracy on both types of spelling tests, and

that more errors were made on the recognition test. However, the treatment was

not found to interact with test type. In the third study, Brown failed to show that

exposure to repeated misspellings adversely affected subsequent spelling accuracy

on either a recognition test or a dictation test. Brown concluded that his findings

brought into question assessment and instruction practices that involve exposing

students to misspellings.

Three instructional situations typically involve student exposure to misspellings. First, students are exposed to misspelled words when they are required to

complete proofreading exercises designed to prepare them to take standardized

Downloaded from jlr.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on May 11, 2016

Effects of Proofreading

417

spelling tests or as part of their basal spelling program. Second, students are also

exposed to misspellings due to classroom practices that stem from research regarding invented spelling (Chomsky, 1971a, 1971b; Read, 1971, 1975). Proponents of

invented spelling suggest that a teacher's acceptance of a student's idiosyncratic

spellings will facilitate the development of the student's overall writing ability.

Invented spelling methodology has been suggested as an alternative to basal spelling

programs (Wilde, 1990). Third, students are exposed to self- or peer-generated

invented spellings (misspellings) as a result of the composition process. Wilde

(1992) suggested that students be encouraged to use spelling strategies that promote

greatest writing fluency. These student spelling strategies can involve the use of

placeholder words (a student's deliberate misspellings to facilitate uninterrupted

composition) and invented spellings (a student's own spellings stemming from

linguistic knowledge).

Calkins (1986) and Graves (1983) have also recommended practices that would

result in both peer- and self-generated misspellings. They have both advised teachers to encourage students to attend to content during preliminary draft efforts, while

putting off editing for spelling until they are ready to produce a final draft, if one

is desired. Calkins (1986) and Graves (1983) also have suggested that students help

each other with draft revision. Wilde (1992) has advised that teachers of beginning

writers require them to proofread and correct only a few of their invented spellings

during the final draft process, leaving the majority of their invented spellings uncorrected. Calkins (1986) and Wilde (1992) have also recommended that teachers

display their students' rough drafts containing invented spellings as a sign of acceptance and pride.

The findings of Caisley (1982), Jacoby (1983), and Brown (1988) suggest that

exposure to misspelled words as part of a proofreading task can adversely affect

subsequent spelling accuracy. The following study was designed to investigate the

effects of proofreading on spelling accuracy. The major purpose of the study was

to investigate the effects of repeated exposures to misspelled words and correctly

spelled words as part of a proofreading task on spelling accuracy. The treatment

involved proofreading exercises that required students to decide whether underlined

stimulus words embedded in sentences were correctly spelled or misspelled. The

participants were elementary school children. Spelling accuracy, the dependent

variable, was measured with dictated tests consisting of the words used in the

proofreading treatment.

The study was designed to accomplish several ancillary purposes. An investigation was made of the effects of the proofreading treatment in terms of two types

of words (predictable and unpredictable sound/spelling correspondence) on spelling

accuracy. In addition, the interaction between student spelling ability and the proofreading treatment on spelling accuracy was investigated. The sample was divided

into three ability groups in terms of their pretest spelling scores, and the treatment

effects on posttest spelling accuracy were ascertained for each group. Lastly, a

Downloaded from jlr.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on May 11, 2016

418

Journal of Reading Behavior

study was made of spelling accuracy pretest/posttest improvement and decrement

scores.

METHOD

Subjects

Ninety-one fifth-grade students from five elementary schools in an urban,

Southwestern United States school district participated in the study. The sample

consisted of 54 females and 37 males with a mean age of 11.0 years. The ethnic

composition of the sample was 52% Anglo, 31% Hispanic, 10% African American,

and 7% other groups, including Native American and Asian American. Although

107 students were present for the pretest, 16 were excluded from the study because

they failed to attend all the testing and treatment sessions. No significant difference

was obtained between the mean error scores for the retained participants

(M= 32.38) and the excluded children (M = 32.20).

Materials

Ninety experimental spelling words were randomly selected from a list of 400

words in a widely used elementary school spelling program, the Macmillan Spelling

Series (Smith, 1983). The 90 experimental spelling words consisted of 45 predictable and 45 unpredictable words. Predictable words had consistent sound-spelling

correspondence to the extent that their correct spellings were predicted by the

algorithm devised by Hanna, Hanna, Hodges, and Rudorf (1966); unpredictable

words were those misspelled by the algorithm. The predictable and unpredictable

words were matched for difficulty on the basis of frequency of occurrence in print

according to the Standard Frequency Index (Carroll, Davies, & Richman, 1971).

The 90 experimental words were taken from Macmillan Spelling Series third

through sixth spellers with a majority of the words from the fifth speller. The

resulting 90-word spelling list was used to construct the pretest, the proofreading

treatment materials, and the two posttests.

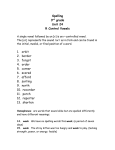

Three sets of proofreading exercises were developed for each of four days of

treatment. The sets of proofreading treatment exercises were color coded as White,

Blue, and Green. For each treatment day, the three sets consisted of 90 sentences

containing the 90 experimental words (one experimental stimulus word per sentence). The experimental spelling words were presented in context to provide syntactic and semantic information to eliminate homophone confusions as sources of

error. Each stimulus word was underlined to differentiate it from the remaining

words in its sentence. Each underlined stimulus word was either correctly spelled

or misspelled depending on the exercise set. To illustrate, the following sentence

Downloaded from jlr.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on May 11, 2016

Effects of Proofreading

419

Table 1

Latin Square Design Used to Control for Word Difficulty Across

Exposures Conditions

Words

Group A

Group B

Group C

N Students

White

Exercise Set

Blue

Green

Always Misspelled

Twice Misspelled

Never Misspelled

Never Misspelled

Always Misspelled

Twice Misspelled

Twice Misspelled

Never Misspelled

Always Misspelled

31

31

29

Note. Always Misspelled = 4 exposures to misspelled word, Never Misspelled = 4 exposures to correctly

spelled word, Twice Misspelled = 2 exposures to misspelled word and 2 exposures to correctly spelled

word.

was used on the first treatment day for the experimental spelling word uncle (misspelled version = unkel), "My aunt and uncle (or unkel) came for dinner." The 90

treatment sentences in an exercise set contained either correct or incorrect spellings

of the 90 experimental words. A different order of presentation and a different set

of sentences was used for the 90 experimental words on each treatment day. For

example, the sentence used for uncle on the second treatment day was, "My uncle

is a pilot."

Within each color-coded exercise set a third of the words were misspelled four

times, a third were misspelled twice and correctly spelled twice, and a third were

correctly spelled four times. Thus, the three color-coded proofreading exercise

sets contained three treatment conditions in terms of frequency of exposure to

misspellings: always misspelled, twice misspelled, and never misspelled. Ninety

words were used to provide adequate test length (n = 15 words) for each of the six

conditions studied (predictable versus unpredictable words by always, twice, and

never misspelled exposure frequency conditions).

A Latin square was used to counterbalance for word difficulty across the three

misspelling exposure frequency conditions. The 90 experimental words were randomly assigned to one of three word groups, designated A words, B words, and

C words. Each of the three groups of 30 words consisted of 15 predictable and 15

unpredictable words. The three word groups were then assigned different misspelling exposure conditions for each of three sets of color-coded exercises. Each participant was randomly assigned to one of the three color-coded exercise sets. During

the 4 days of treatment, students assigned to a particular color-coded exercise set

were given each of the three misspelling exposure conditions by word group.

Following the Latin square methodology (see Table 1), the students assigned to

Downloaded from jlr.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on May 11, 2016

420

Journal of Reading Behavior

the White exercise set saw the 30 A-group words misspelled four times, the 30

B-group words misspelled twice and correctly spelled twice, and the 30 C-group

words correctly spelled four times; students assigned to the Blue set saw the 30

A-group words correctly spelled four times, the 30 B-group words misspelled four

times, and the 30 C-group words misspelled twice and correctly spelled twice;

students assigned to the Green set saw the 30 A-group words misspelled twice and

correctly spelled twice, the 30 B-group words correctly spelled four times, and the

30 C-group words misspelled four times. Word predictability and proofreading

exposure frequency were within-student repeated measures. Color-coded exercise

set was a between-student variable; 31 students completed the White set, 31 completed the Blue set, and 29 completed the Green set.

On any given proofreading exercise set, half of the words were misspelled and

half of the words were spelled correctly. One misspelling was consistently used

for each experimental word across all treatment materials. The misspellings were

chosen from lists of reasonable misspellings suggested by six students enrolled in

a graduate level reading diagnosis course. The six graduate students had experience

teaching reading and spelling in regular elementary school classrooms, Chapter I

classes, and/or special education classes. The location of errors within words (beginning, middle, end) was balanced as much as possible, and a variety of error

types (omissions, insertions, substitutions, and transpositions of letters) was represented in the list of 90 experimental word misspellings. Table 2 provides the list

of experimental spelling words together with their respective misspellings.

Separate answer sheets were prepared to accompany the treatment exercise

sets. The separate answer sheets included a written set of directions, and a means

to respond to the 90 treatment items. The provided written directions instructed the

students to read each sentence silently as it was being read aloud to them, look at

the underlined word in the sentence, decide whether it was correctly spelled or

misspelled, match the number of the sentence with the number on the separate

answer sheet, and fill in the appropriate bubble on the answer sheet. Two columns

of bubbles were provided for response with one column under the heading correct

and the other column under misspelled.

Three dictation spelling tests (the pretest and two posttests) were constructed

using the 90 experimental words. The three tests were identical in format and

content except for item order. The order of the spelling words was determined

separately for each test by random assignment. The dictation tests were similar to

those used to assess spelling in most commercially published elementary school

spelling progams. The examiner's copy listed the 90 experimental spelling words

together with their respective stimulus sentences. Stimulus sentences were used

to reduce student phone discrimination confusions and to eliminate homophone

confusions as sources of error. The students were provided with answer sheets

consisting of 90 numbered underlined spaces to use to write the 90 dictated experimental spelling words.

Downloaded from jlr.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on May 11, 2016

Table 2

Correct and Misspelled Versions of Predictable and Unpredictable Experimental

Spelling Words

Correct

Predictable Words

Misspelled

able

about

chocolate

dime

dull

early

empty

entertainment .

entire

expect

explain

fear

fence

finger

force

fresh

frost

glad

had

hero

institution

kitchen

left

this

mouse

middle

napkin

next

plant

political

proof

pumpkin

puzzle

prize

rock

tomato

trip

section

spend

storm

strong

teeth

usual

vacation

whisper

abel

abaut

choclate

dyme

dul

earley

emty

entertanement

intire

espect

explane

feer

fense

fingur

forse

fersh

frawst

gladd

hed

herow

institusion

kichen

lift

thiz

mowse

middel

napken

nekst

palant

politick

pruf

pumken

puzzel

prise

roc

tomatoe

trep

sektion

spind

Strom

stron

teethe

uzual

vacasion

wisper

Unpredictable Words

Correct

Misspelled

accident

address

although

awful

between

bicycle

braid

breakfast

build

campaign

chicken

community

electricity

enough

eraser

everyone

feather

freight

fountain

governor

island

juice

knife

knowledge

ladder

library

many

medicine

myself

music

necessary

often

pardon

pencil

raise

ready

scissors

soap

straight

stream

sugar

terrible

tomorrow

toward

uncle

Downloaded from jlr.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on May 11, 2016

axcidant

adress

allthough

awfull

betwene

bycicle

brade

brekfast

bild

campain

chiken

comunity

electrisity

anough

eraiser

evryone

fether

frate

fountin

governer

islend

juise

nife

knowlege

laddir

liberry

meny

medasin

mysself

muzic

nesessary

ofen

parden

pensul

rayse

reddy

sissers

sope

strate

streeme

shuger

terrable

tommorrow

toard

unkel

422

Journal of Reading Behavior

Procedure

The tests and treatments were presented in the participants' regular classroom

by the researchers. The participating students were tested and given the proofreading treatment over an eight day cycle. The students were given the spelling dictation

pretest on the first day of the cycle, Monday. On Tuesday through Friday, the

students were given one set of proofreading exercises per day until four sets were

completed. On Friday after the students had finished the fourth proofreading exercise, they were allowed a short break and then were given the first dictated spelling

posttest to measure immediate treatment effects. The second dictated spelling posttest was administered on the following Monday to measure delayed treatment effects. Each of three dictated 90-word spelling tests took approximately 30 minutes

to administer. Within classes, the researchers gave the tests and treatments at the

same time during each of the six days of testing and treatment. Across classes, the

researchers collected data at various times during the morning and afternoon with

the schedules set to meet the needs of the participating teachers.

The same procedure was followed for each of the four proofreading treatment

sessions. At the beginning of each daily exercise, the examiner read aloud the

answer sheet directions instructing the students to silently read the 90 sentences,

proofread the embedded underlined stimulus words for spelling correctness, and

mark on the answer sheet whether each underlined word was correct or misspelled.

As the students worked through the exercises, the researcher read each of the 90

exercise sentences aloud and repeated the underlined stimulus word to insure that

potential reading problems did not confound the treatment. For example, the treatment sentence, "We read the entire book before lunch," was read aloud as "We

read the entire book before lunch . . . entire." After the examiner read aloud each

sentence, she/he paused briefly before reading the next sentence to allow the students time to mark their separate answer sheets. Students were not given feedback

regarding the correctness of their responses to the proofreading exercises. Completion of the proofreading exercises required approximately 30 minutes of class time

per day.

The same procedure was followed on the three dictation spelling tests: the

students listened as the researcher pronounced the spelling word, read aloud a

sentence containing the word, and pronounced the word again. The students responded by writing each dictated word on their answer sheets. The same stimulus

sentences were used for the 90 spelling words across the three tests. Spelling error

scores were obtained for each of the three spelling dictation tests by identifying

and counting student responses that deviated from conventional American English

spelling.

This method resulted in a 3 x 2 x 3 within-subject factorial design: 3 proofreading spelling exposure frequencies (4, 2, and 0 misspellings) X 2 spelling word

Downloaded from jlr.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on May 11, 2016

Effects of Proofreading

423

types (predictable and unpredictable) X 3 testing times (pretest, immediate posttest, and delayed posttest).

RESULTS

A mixed factorial ANOVA was used to analyze pretest spelling error scores

for differences attributable to word predictability or student spelling ability. The

results indicate that the main effect of word predictability was significant, F ( l ,

88) = 291.7, p<.0001, meaning that unpredictable words were misspelled more

frequently than predictable words. Pretest spelling error scores for students assigned

to the three color-coded excercise sets did not differ significantly, indicating that

random assignment had effectively controlled differences among students prior to

exposure to the proofreading treatments.

Proofreading misspelled words was expected to increase spelling errors during

posttesting, and the effects of the proofreading treatments were first tested using a

mixed factorial ANOVA for repeated measures. As expected, the main effects for

testing time (pretest, immediate posttest, and delayed posttest), and for exposure

frequency (always misspelled, twice misspelled, and never misspelled) were significant: F(2, 176) = 57.9,p<.0001, andF(2, 176)= 106.4,/?<.0001. The interaction of testing time and exposure condition was also significant, F(4, 352) = 54.4,

/j<.0001. Thus, there were changes in spelling error scores following the proofreading treatments, and the changes were related to the number of exposures to

misspellings of the experimental words.

However, inspection of the mean spelling error scores for the different exposure frequency conditions indicated that the treatment effects were somewhat different than originally expected (see Table 3). Exposure to misspellings had negligible

effects while exposure to correct spellings had substantial effects. There was only

a very slight increase in the number of spelling errors on the immediate posttest

for both predictable and unpredictable words that were always misspelled in the

proofreading exercises. The delayed posttest results for the always misspelled exposure frequency condition were insignificant and contradictory for word type. Although students made a few more delayed posttest spelling errors on unpredictable

words, they made a few less delayed posttest errors on predictable words. But the

mean spelling error score differences between the pretest and the two posttests

following treatment exposure to correct spellings were substantially larger. Student

mean spelling error scores decreased for words (both predictable and unpredictable)

that were spelled correctly in the proofreading exercises, even when the correct

spellings were only presented twice and accompanied by two misspelling presentations during the treatment. Students made even fewer posttest spelling errors on

words that were always spelled correctly in the proofreading treatment exercises.

For words that were twice misspelled (twice correctly spelled) and never misspelled

Downloaded from jlr.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on May 11, 2016

Journal of Reading Behavior

424

Table 3

Means and (Standard Deviations) of Spelling Error Scores for Predictable and

Unpredictable Words by Exposure Condition

Always

Misspelled

Exposure Condition

Twice

Misspelled

Never

Misspelled

Predictable Words

Pretest

1st Posttest

2nd Posttest

4.1 (3.3)

4.5 (3.1)

3.9 (3.0)

4.0 (3.6)

2.9 (2.7)

3.2 (2.8)

4.0 (3.3)

2.4 (2.5)

2.6 (2.8)

Unpredictable Words

Pretest

1st Posttest

2nd Posttest

6.8 (3.7)

7.2 (3.6)

7.0 (3.6)

6.6 (4.1)

5.2 (3.4)

5.3 (3.6)

6.8 (4.0)

4.6 (3.5)

4.7 (3.4)

Word Type

(always correctly spelled), mean spelling error scores for the delayed posttest did

not differ significantly from those for the immediate posttest, indicating that improvements in spelling accuracy attributable to exposures to correct words endured

over the 3-day interval between posttests.

Caisley (1982) suggested that students differing in spelling ability might respond differently to proofreading lessons, and she recommended further investigation of the relationship between ability and learning from proofreading. More specifically, Caisley thought proofreading might have benefits for poorer spellers but

not for students of better ability. Her suggestions seemed especially interesting in

light of earlier studies by Gilbert (1934, 1935) that indicated poorer spellers were

less able to learn spellings from reading than were better spellers.

It was assumed that a student's error score on the pretest was a reasonable

estimate of spelling ability, and an additional ANOVA was done to determine

whether the effects of the proofreading treatments used in this study would support

either Caisley's predictions or Gilbert's. In other words, would students who misspelled more words on the pretest improve more or less following the proofreading

treatments than those who misspelled fewer words on the pretest?

Since spelling errors for predictable and unpredictable words were significantly

correlated (r=.92, p<.001), the number of incorrect pretest spellings of all 90

experimental words was used to establish three ability groups of good, average,

and poor spellers. The good spellers (« = 30, M= 11.0) misspelled 3 to 21 words

on the pretest; the average spellers (n = 30, M=30.5) misspelled 22 to 37 words;

the poor spellers (n = 31, M=54.3) misspelled 38 to 76 words.

The analysis was again a mixed factorial ANOVA for repeated measures. The

Downloaded from jlr.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on May 11, 2016

Effects of Proofreading

425

Table 4

Means and (Standard Deviations) of Spelling Error Scores for the Three Student

Spelling Ability Groups by Exposure Condition

Ability Group

Always

Misspelled

Exposure Condition

Twice

Misspelled

Good Spellers

Pretest

1st Posttest

2nd Posttest

3.9 (2.8)

5.5 (3.4)

5.2 (3.3)

3.4 (2.6)

2.7 (2.3)

2.9 (2.2)

3.7 (3.2)

2.0 (2.2)

2.1 (1.8)

Average Spellers

Pretest

1st Posttest

2nd Posttest

10.5 (3.5)

10.9 (3.2)

10.1 (3.7)

9.4 (3.6)

7.0 (2.9)

7.7 (3.1)

10.6 (3.9)

6.2 (2.8)

6.3 (3.5)

Poor Spellers

Pretest

1st Posttest

2nd Posttest

18.0 (4.8)

18.4 (5.1)

17.4 (5.2)

18.5 (5.9)

14.3 (5.3)

14.6 (5.7)

17.9 (5.6)

12.4 (5.9)

13.2 (5.9)

Never

Misspelled

main effects for ability group (good, average, and poor), for test time (pretest,

immediate posttest, delayed posttest), and for exposure frequency (always misspelled, twice misspelled, and never misspelled) were all significant: F{2,

88)= 162.0, p<.0001, F(2, 176) = 73.7, /><.0001, and F(2, 176) = 87.1,

p<.0001. But the result of most interest was that the interaction of ability by

exposure frequency was not significant. Thus, although spellers of all three ability

levels decreased spelling errors following exposure to correct spellings in the proofreading treatment exercises, the decrease was not related to spelling accuracy on

the pretest. This result did not support Caisley's report that poorer spellers gained

more from proofreading. But neither did it support Gilbert's conclusion that poorer

spellers gained less from reading than better spellers. The mean spelling error

scores for good, average, and poor spellers are presented in Table 4.

Exposure to misspelled words during the treatment did not significantly affect

the spelling accuracy of the students in the sample. However, an inspection of the

data revealed that the students in the sample varied from each other in terms of the

extent to which their spelling accuracy was increased or reduced by the three

experimental exposure conditions. Given this information, it was felt that even

though exposure to misspellings may not have had a general effect on the entire

sample of students, it was possible that it might have affected a subgroup of

outlier students. Therefore, an analysis of this student score variation was made by

Downloaded from jlr.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on May 11, 2016

426

Journal of Reading Behavior

Table 5

Number of Students Obtaining CI and IC Difference Scores for Always

Misspelled and Never Misspelled Exposure Conditions

Size of Difference

Exposure Condition

Always Misspelled

Never Misspelled

CI

CI

IC

IC

18

17

21

15

12

2

6

7

8

9

10

11

13

7

12

17

20

17

10

3

3

0

2

0

0

0

Total N Students

91

0

1

2

3

4

5

2

2

2

0

0

0

0

35

34

16

3

2

1

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

6

7

8

11

15

8

11

91

91

91

5

6

5

4

3

2

Note. CI = Correct spelling on the pretest and incorrect spelling on the immediate posttest; IC = Incorrect

spelling on the pretest and correct spelling on the immediate posttest.

computing difference scores between the pretest and the immediate posttest for two

of the three exposure conditions, always misspelled and never misspelled. The data

were tallied in terms of the two possible types of difference scores, decrement or

CI scores (CI = correct on the pretest, incorrect on the posttest), and improvement

or IC scores (incorrect on the pretest, correct on the posttest). An inspection of

Table 5 reveals several distinct patterns.

The students had greater difficulty maintaining their level of spelling accuracy

under the always misspelled exposure condition than under the never misspelled

condition. Only 7 students were able show no decrement (CI = 0) under the always

misspelled condition, whereas 35 of them showed no decrement under the never

misspelled condition.

Some of the students obtained rather extreme decrement scores and these, too,

were related to the spelling exposure condition. CI scores of 5 or greater were

obtained by 18 of the students under the always misspelled condition, whereas only

1 student had a decrement of 5 and none scored greater than 5 under the never

misspelled condition. Extreme CI scores were obtained by a few of the students

under the always misspelled condition, with 3 students misspelling 7 words on the

Downloaded from jlr.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on May 11, 2016

Effects of Proofreading

All

posttest that they had previously spelled correctly, and another 2 students misspelling 9 words that they had previously spelled correctly.

Most of the students showed some improvement under both exposure conditions, but the students obtained IC scores of greater magnitude under the never

misspelled condition than under the always misspelled condition. Eighteen students

showed no improvement under the always misspelled condition, whereas only 6

showed no improvement under the never misspelled condition. IC scores of 5 or

greater were obtained by only 8 of the students under the always misspelled condition, whereas 44 of them improved their spelling accuracy by 5 or more words

under the never misspelled condition. Although none of the students under the

always misspelled condition were able to obtain IC scores of 9 or greater, 14 of

them under the never misspelled condition improved their accuracy by 9 or more

words, with 3 of them improving by 11 words and another 2 improving by 13

words.

DISCUSSION

The proofreading (misspelling detection) exercises used in the present study

provided a means for investigating the instructional effects of proofreading exercises similar to those commonly used in classrooms. The one difference between

the procedure used in this study and normal classroom practice was the number of

times students were exposed to the misspelled words. Students were exposed to as

many as four misspellings of the same words across four treatment days in this

study. In the typical spelling curriculum, students may be asked to study lists or

sentences with embedded misspellings to locate errors no more than once a week.

Furthermore, misspellings of words are seldom repeated in published spelling instructional materials. A second deviation from typical classroom practice was that

the experimental proofreading exercises were read aloud by the researchers to

the participating students as they followed along and attempted the experimental

proofreading task. In contrast, most classroom proofreading tasks are attempted

independently by students with no listening component. A third limitation was the

underlining of the stimulus words in the proofreading treatment sentences.

Several other limitations should be mentioned regarding this study. The sample

of experimental spelling words was intended to represent the population of spelling

words commonly taught by fifth grade, but there may have been some bias in the

word selection process. Only one of the many commercial spelling series was used

in developing the initial word pool, and selection from that series was restricted

by the decision to choose word pairs consisting of a predictable word and an

unpredictable word on the basis of frequency of appearance in print (Hanna, Hanna,

Hodges, & Rudorf, 1966). Furthermore, even though the two types of words

selected (predictable and unpredictable) were equivalent in terms of frequency of

Downloaded from jlr.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on May 11, 2016

428

Journal of Reading Behavior

use, the predictable words were much easier for the students to spell. As a result,

effects of exposure to correct spellings were attenuated for predictable words.

The most significant finding of this study is that exposure to correct spellings

had a significant positive effect on spelling accuracy. Average spellers typically

learned the correct spellings of one or two predictable words and two or three

unpredictable words as a result of their exposure to the correct spellings of those

words during the experimental proofreading tasks. The delayed posttest results

indicated that those gains in spelling accuracy were durable.

Improvements in spelling accuracy were directly related to the number of times

the experimental words were spelled correctly in the exercises. The amount of gain

was related to the number of times (0, 2, or 4) a correctly spelled word was

proofread. Similar trends were observed for good, average, and poor spellers,

although the rate of improvement in spelling predictable words was less for good

and average spellers than poor spellers. This may partly be attributed to an error

score floor effect for the average and good spellers because their pretest scores

revealed that they already knew how to spell most of the predictable words.

Caisley (1982) found that her subjects did worse on written spelling tests when

they were given additional proofreading exercises. Jacoby's (1983) observations

and Brown's (1988) findings suggest that viewing misspellings can interfere with

subsequent ability to produce correct spellings. The findings of Caisley (1982),

Jacoby (1983), and Brown (1988) have possible implications for (a) spelling instruction that involves proofreading exercises with embedded misspellings and (b)

composition and spelling practices that insure multiple exposures to student spelling

inventions.

Therefore, it was encouraging to discover that the proofreading tasks used in

this study did not have significant detrimental effects on the spelling accuracy. It

was found that repeated exposures to misspellings neither helped nor harmed spelling accuracy of most of the children who participated in this study. This should be

considered to be a fairly robust finding because the participating students viewed

a misspelling of a word as many as four times during a 1-week interval, an experience with repeated misspellings likely to exceed anything they might encounter in

a typical classroom.

Although the student sample as a whole was not significantly affected by

repeated exposures to misspellings during the experimental proofreading task, a few

students exhibited substantial loss of spelling accuracy following those experiences.

Eight of the 91 students had decrement scores of 6 or more words under the always

misspelled condition, and 2 of those 8 students missed 9 words on the posttest that

they spelled correctly on the pretest. It may be that students similar to these outliers

require special consideration during spelling and composition instruction.

Fernald (1943) may have had students similar to these outliers in mind when

she recommended that, " . . .the original (student) paper with the misspelled words

Downloaded from jlr.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on May 11, 2016

Effects of Proofreading

429

should not be given back to the pupil unless these words are completely blacked

out and the correct forms written in their place" (p. 204). Despite Clay's (1975)

pioneer contribution regarding the role of invented spelling in a child's development

of writing competence, she later advocated a practice similar to Fernald's for

beginning reading students with high potential for failure. Clay (1985) suggested

that a spelling error occurring during the writing component of a Reading Recovery

lesson be masked, and that the teacher have the child " . . . get a correct attempt

under way with help" (p. 64). It should also be noted that both Fernald (1943)

and Clay (1985) advocated prompt exposure of a word's correct spelling after

removal of the misspelled version. This practice is consistent with the major finding

of this study, exposure to correct spellings facilitates spelling accuracy.

An inspection of the students' pretest and posttest responses suggests there

was some tendency toward misspellings that conformed to the experimental misspellings. For example, one student correctly wrote SPEND on the pretest, then

wrote SPIND (the experimental misspelling) on the immediate posttest, and then

reverted again to SPEND on the delayed posttest. In some cases, the provided

misspelled stimulus words gave partial information regarding spelling accuracy.

For example, a student wrote BREDFUST on the pretest, but BREKFAST (the

experimental misspelling of breakfast) on both posttests. This student actually

profited from repeated exposures to the provided misspelled stimulus word (brekfast) as it enabled her to subsequently produce a response on the posttests, (BREKFAST) that was closer to the correct spelling (one letter omitted) than her original

response (BREDFUST = two letters substituted and one omitted).

Exposure to a misspelled exercise stimulus word during the proofreading treatment occasionally facilitated subsequent spelling accuracy. To illustrate, one student spelled electricity as ELECTRECITY on the pretest. After being exposed to

the stimulus misspelling electrisity four times during the 4 days of treatment, the

student subsequently spelled the word correctly on the two posttests. The portion

of the word that this student had missed originally on the pretest was correct in the

provided misspelled stimulus word during the treatment. It appears that this student

profited from this proofreading experience, learning that the third vowel in electricity is an i rather than an e. In addition, this student appeared to choose to ignore

the substitution of s for c in the misspelled stimulus word electrisity. In such cases

as these, the provided misspelled stimulus words actually contained clues as to

how to correct previously misspelled words.

Gains in spelling accuracy appeared to be a function of word difficulty and

spelling ability. Because the 90 experimental words varied in difficulty, poor spellers had the opportunity to improve their spellings of easy words, whereas better

spellers could improve their spelling of more difficult words. The range of difficulty

that defined the experimental words allowed most of the students in the sample to

perform at their own spelling instructional levels. And at the level where learning

and improvement occurred for a particular student, that child was able to ignore

Downloaded from jlr.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on May 11, 2016

430

Journal of Reading Behavior

misspellings and attend to correct spellings. These observations suggest that it is

likely that some level of prior knowledge about how a word looks may determine

the ease of learning to spell that word.

The results of this study raise doubt regarding the efficacy of using proofreading exercises for the teaching of spelling. Given that standardized tests often use

proofreading-type items to test spelling knowledge, it might be argued that students

should be given proofreading exercises in preparation for testing. Yet, Caisley

(1982) found that most students given proofreading practice did no better on a

recognition spelling test than students who did not have that practice. The low

achieving students in Caisley's sample who were able to somewhat improve their

recognition spelling test scores showed no improvement in written spelling accuracy. Thus, proofreading appears to be a dubious method of improving spelling

performance even as a preparation for standardized testing.

Future Directions

This study raises several questions that can serve to stimulate future research

regarding how students learn to spell and the relationship between reading and

spelling. While most of the students in this study were relatively unaffected by

exposure to misspellings, a few outliers were dramatically affected. It appears

warranted to conduct research to find out why the spelling accuracy of some students is impaired by exposure to misspellings whereas that of others is not.

Smith's (1982) notions regarding the interrelationship between reading and

writing were supported by this study's finding that the proofreading of correctly

spelled words improved spelling accuracy. Krashen (1989) has proposed an Input

Hypothesis regarding vocabulary and spelling acquisition which proposes that extent of reading experience improves spelling accuracy. Although this study did not

investigate incidental learning due to reading experience, its finding that spelling

accuracy was increased due to exposure of correct spellings during proofreading

was consistent with Krashen's Input Hypothesis. In addition, Supramanian (1983)

found proofreading to be related to reading ability and suggested that this relationship was probably due to reading experience involving the correct forms of the

words. Therefore, additional research regarding the relationship between proofreading and spelling may offer one way to help us better understand the nature of the

reading and writing connection.

It appears appropriate to conduct proofreading/spelling research connected

with invented spelling methodology. Wilde (1992) has suggested that invented

spellings should have no adverse effect on subsequent spelling accuracy because

children are aware that " . . . their invented spellings are different from standard

spellings and don't put any energy (conscious or unconscious) into remembering

them" (p. 157). On the other hand, Wilde condemned using basal spelling program

proofreading exercises because the misspellings seen in print might cause future

Downloaded from jlr.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on May 11, 2016

Effects of Proofreading

431

confusion. Research regarding the effects of exposure to contrived misspellings

versus invented spellings on spelling accuracy seems appropriate.

Calkins (1986), Graves (1983), and Wilde (1992) suggest that students edit

their own first draft efforts as well as those of their peers for spelling and other

factors. It appears that proofreading/spelling research should be conducted within

the context of composition instruction.

REFERENCES

Allen, D., & Ager, J. (1965). A factor analytic study of the ability to spell. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 25, 153-161.

Allred, R. A. (1984). Spelling trends, content, and methods: What research says to the teacher. West

Haven, CT: National Education Association.

Brown, A. S. (1988). Encountering misspellings and spelling performance: Why wrong isn't right.

Journal of Educational Psychology, 80, 488-494.

Caisley, K. (1982). Evaluation of implementing proofreading into the school spelling program. Educational Research Institute of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 221 880)

Calkins, L. M. (1986). The art of teaching writing. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Carroll, J. B., Davies, P., & Richman, B. (1971). American heritage word frequency book. Boston:

Houghton-Mifflin.

Chomsky, C. (1971a). Invented spelling in the open classroom. Word, 27, 499-551.

Chomsky, C. (1971b). Write first, read later. Childhood Education, 47, 296-299.

Clay, M. M. (1975). What did I write? Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Clay, M. M. (1985). The early detection of reading difficulties. Aukland, New Zealand: Heinemann.

Fernald, G. (1943). Remedial techniques in basic school subjects. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Gilbert, L. C. (1934). The effect of reading on spelling in the secondary schools. California Quarterly

of Secondary Education, 9, 269-275.

Gilbert, L. C. (1935). A study of the effect of reading on spelling. Journal of Educational Research,

28, 570-576.

Goodman, K. S. (1984). Unity in reading. In A. C. Purves & O. Niles (Eds.), Becoming readers in a

complex society. Eighty-third Yearbook of the National Society for the Study of Education (pp.70113). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Graham, S., & Miller, L. (1979). Spelling research and practice. Focus on Exceptional Children,

12, 1-16.

Graves, D. H. (1983). Writing: Teachers and children at work. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Hanna, P. R., Hanna, J. S., Hodges, R. E., & Rudorf, E. H. (1966). Phoneme-grapheme correspondences as cues to spelling improvement (Department of Health, Education, and Welfare; Publication No. OE-32008). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Hieronymus, A. N., Hoover, H. D., & Lindquist, E. F. (1988). Teachers guide: Iowa tests of basic

skills, Multi-level Battery, Form J, Levels 9-14. Chicago: Riverside.

Jacoby, L. L. (1983, November). Effects of recent prior experience on spelling. Paper presented at the

Twenty-fourth Meeting of the Psychonomic Society, San Diego, CA.

Kottmeyer, W., & Claus, A. (1980). Basic goals in spelling. New York: Webster Division,

McGraw-Hill.

Krashen, S. (1989). We acquire vocabulary and spelling by reading: Additional evidence for the Input

Hypothesis. The Modern Language Journal, 73, 440-464.

Downloaded from jlr.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on May 11, 2016

432

Journal of Reading Behavior

Madden, R., & Carlson, T. (1963). HBJ spelling. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

National Commission on Testing & Public Policy (1990). From gatekeeper to gateway: Transforming

testing in America. Chestnut Hill, MA: National Commission on Testing & Public Policy, Boston

College.

Niemi, P., & Virjamo, M. (1986). Proofreading: Visual, phonological, syntactic or all of these? Journal

of Research in Reading, 9, 31-38.

Personke, C., & Knight, L. (1967). Proofreading and spelling: A report and a program. Elementary

English, 44, 768-774.

Read, C. (1971). Pre-school children's knowledge of English phonology. Harvard Educational Review,

41, 1-34.

Read, C. (1975). Children's categorizations of speech sounds in English. Urbana, IL.: National Council

of Teachers of English.

Shepard, L. A. (1991). Will national tests improve student learning? Kappan, 73, 232-238.

Shores, J. H., & Yee, A. H. (1973). Spelling achievement tests: What is available and needed? Journal

of Special Education. 7, 301-309.

Smith, C. (1983). Macmillan spelling series. Riverside, NJ: Macmillan.

Smith, F. (1982). Writing and the writer. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

Smith, M. L. (1989). The role of external testing in elementary schools. Los Angeles: Center for

Research on Evaluation, Standards, and Student Testing, UCLA.

Supramanian, S. (1983). Proofreading errors in good and poor readers. Journal of Experimental Child

Psychology, 36, 68-80.

Thomas, O., Thomas, I. D., & Lutkus, A. (1978). The world of spelling. Lexington, MA: D. C. Heath.

Vallecorsa, A. L., Zigmond, N., & Henderson, L. M. (1985). Spelling instruction in special education

classrooms: A survey of practices. Exceptional Children, 52, 19-24.

Valmont, W. I., & Valmont, R. W. (1980). Spelling. New York: American Book.

Wilde, S. (1990). A proposal for a new spelling curriculum. The Elementary School Journal, 90,

275-289.

Wilde, S. (1992). You kan red this.' Spelling and punctuation for whole language classrooms, K-6.

Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Downloaded from jlr.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on May 11, 2016