* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download 09_chapter 2

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

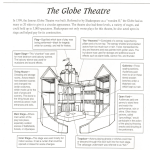

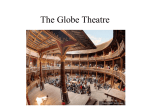

CHAPTER - II SHAKESPEAR'S THEATER The theatre of Shakespeare‟s day was the culminated of a long development and the amalgation of many desperate influences. It was also known as the accurate mirror of the diversity of Elizabethan period‟s life.”1 The expanding intellectual horizons of the Elizabethans were evident in the materials of the playwrights. Geography, history, mechanics, recent inventions, popular science, legislation, preventive medicine, as honomy, natural history, civic affairs, and gossip all found their way into the theatre, to be consumed with avid interest by the audiences. In addition to its capacity for welcoming all lands of information the Elizabethan audiences- like perhaps no other was merald by its devotion to the spoken word. Listening was easier than reading and the audience was quick to respond to oratory or repartee.”2 LONDON BECOMES THE CENTRE: The Sixteenth century Englishmen could see dramatic performances throughout the kingdom, but playhouses were built only in London. Some nameless businessmen of vision aware of the growing popularity of the plays rented a few of the large inns in London and made them permanent playing places, erecting permanent stages in the Innyards, this development permitted very much better staging, the use of more properties and a measure of 1 2 On stage- A History of theatre by Vera Mowry Roberts published by Harper and Row, New York Evaston Page-138. ALB RIGHT, VICTOR E., The Shakespearian Stage, Columbia University Press, New York, 1909. Page-158. security for the acting companies."1 London now had real playhouses and the drama was even more for the natural amusement. The eight public playhouses including the hope, were in the order of erection: (i) The Theater (ii) The Curtain (iii) The Rose (iv) The Swan (v) The Globe (vi) The Hope (Vii) The Fortune (viii) The Red Bull"2 (i) THE THEATER:- The property was leased on April 13,1576 by Giles Allen to James Burbage of the Carl of Leucister company who spent, according to a statement made in legal papers, 600 pounds in constructing a play house. It was built of wood and was probably round in form with gallery about the plot in the center, like the other public play houses, but no picture of it survive" 3. Stockwood in his sermon at Paul's cross, august 1578, calls it ''The gorgeous playing place' erected in the fields when the base expired in 1597, are dispute arose between Allen and Cuthbert and Richard, the son of John Burbage renewel. During the dispute, 1597-98 the Burbage still remained as tenants, but the finally took advantage of their rights in the base and in December to January 1598-99, they pull 1 2 3 Adams, Joseph Quincy, A life of William Shakespeare, constable and company, Ltd; London, 1923. Page-74. A short discourse of English Stage, 1664, reprinted by Spingarn, critical Essays of the Seventeenth Century. Page-92. Baker, George PTERCE THE DEVELOPMENT of Shakespeare as a Dramatist, front piece of London in 1610. Page-160 down the theatre and carried the timber to the bank side where they used this material in erecting the GLOBE''1 (ii) THE CURTAIN:- Within a few months of the building of the theater in 1576, the Curtain was built close by probably on the south side of Holywell Lane. Both the playhouses are very small but clearly round in shape' and it was doubtless very like the theater and the letter Swan and GLOBE. The name, curiously enough, has nothing to do with a theatrical curtain, but had long been applied to the land on which the curtain was built. It was in control of Henry Laneman in 1585, when he entered into an arrangement of Burbage of the theater to share equally the profits of the two play houses for seven years. Various companies occupied the playhouses during the Elizabeth's regin."2 (iii) THE ROSE:- The rose is the first theater known to have been built on bank side, but the exact date is not certain. In 1585, the lease of the property, known as the Little Rose, north of maiden lane on the corner of Rose alley, was assigned to Shilip Henslowe and on January 10, 1857, he formed a partnership with John Cholmley looking towards the erection of a playhouse on a parcel of this, ninety five feet square and already containing a small tenement. Probably the playhouse 1 2 As above. Page-161. C.W. Wallace, "First London Theatre," University of Nehraska Studies 1913, P-149. was built immediately; at all events the Lord strange's men were acting there on February 19, 1592, when Henslowe opened his account with them in his diary; a book destined to be one of our main fouru's for the stage history of its period. There are building accounts in the dairy dated 1592 but in the opinion of Mr. Greg, these referred to extensive repairs rather than to the original building from them. We get only slight information about the house, which was of wood, round and opened to the sky in the middle, but with a thatched roof over the galleries. In addition to the galleries, there was tiring room in the rare of the stage, a ceiled room over the tiring room (probably the balcony at the near of the stage but possibly a hut like those of the Swan and GLOBE) a lords room or box ceiled and are most for the flag. Later repairs in 1595 include making the throne in the heavens and seem to imply considerable alteration about the ceiled room. Henslowe's diary given an extensive, though not complied, account of plays and accompanies at the rows until 1603. In 1605, Henslowe's lease expired and we don't know what arrangement was made in regend to the theater. Henslowe's sonin-law, Alleyn, paid tithes on the property in 1622 and it was used for prize fright after 1620."1 1 ADAMS, JOSEPH QUINCY, A Life of William Shakespeare, Constable and company Ltd, London 1923, Page-120. (iv) THE SWAN:- The Swan was built about 1594 by Francis Alangley, a well to do property holders. From Vicher's view and the map published by Rendle it appears to have been a twelve sided building similar in the external appearance to the other's theater on the surrey side. It was doubtless used for plays, 1595-97 and was occupied during parts of 1597-98 by the Lord Pembroke's men"1. Hentzner, another traveler declared in 1598 that all the theater were of wood."2 Again, it seems impossible that the Swan could have held three thousand persons; one half that number would have been the maximum. If the description is inaccurate, how about the picture? That rests on no very authentic evidence. It is of uncertain date, based on hearsay evidence, drawn forms description and not forms any direct observation. The drawing indeed represents things which could not be seen at the same time from any single point of view. It is, moreover, self contradictory, for, while the stage is evidently removable, it sustains the pillars which support the heavy superstructure. Further there is no sign of curtains such as appear in the pictures of Elizabethan stage; and such as appear in their pictures of Elizabethan stages and such as are known to have existed in most, if not all of the theatres. The drawing, however, presents the leading features common to Elizabethan theaters. The circular interior, the three tiers of galleries, the stage extending into the pit, the 1 2 C.W. Wallace, " The Swan Theatre and Carl of Pem broke's servants", English she Studies,1911, New York Press, Page-152. The Universal review, June 1888, Quote in Ordesh-268. balcony in the near, the two doors, the hut overhead, the flag and the trumpeter, the heavens or shadow supported by pillars - were all the usual accessories of the public theaters. The hangings curtains" of the Swan are alluded to in a letter of 1602, but it is possible that there were curtains in 1596. The movable stage confirms other evidence that the playhouses was used mainly for non-dramatic entertainments and lesson the importance of the Swan as a representative theater."1 (v) THE GLOBE:- Directly east of the Hope and on the North side of Marden Lane. The Globe was built in 1599 by the Burbages, in part from the timber of the theater. It was round, with a thatched roof over the galleries; and its general construction is known to us, because the fortune, built in the succeeding year, was according to its contract, in most respect modeled after the Globe. In 1613, during a performance of a new play, "All is true". Set forth with many extraordinary circumstances of pamp and majesty, even to the matting on the stage, it caught fire and burned to the ground, the actors and audience escaping in the difficulty through its two narrow doors. It was at once rebuilt, octagonal in form with a tiled roof more substantial construct`ion and a more ornamental interior. The first Globe, the home of Shakespeare's company had been at the time it was built the finest public theater in London, and the new Globe reasserted this primary. Though the King's men now used the Blackfriars as their winter theater, they continued to 1 Chamberlains letters,Camden stc.,-163 act in the Globe during the summers until the civil war. It remained the home of drama long after the other playhouses on the Bankside has been given up to the other purposes. In 1632 Donna Hollandir, looking forth from her fortress - one of the Stews-beheld the dying Swanne, hanging down her head, seeming to say her own dirge" and the Hope, which "wild beasts and gladiators did most posses"; but the Globe was still the continent of the world, because half the year a world of beauties, and have spirits resorted unto it." The house was pulled to the ground on April 15, 1644."1 (vi) THE HOPE:- The hope, built in 1614 for Philip Henslowe, was according to Vischer's view an octagonal structure. The building contract required that it should but closely modeled on the Swan. It had external staircases leading to the galleries, a removable stage supported by the main structure and not by pillars as in the Swan, foundations of brick, and a tile roof. It was designed for bear baiting as well as the drama. The lady Elizabeth's men acted there certain days of the work for a year or two; but no plays, so far as we know, were given after 1616. It was standing in 1632 and was used for prize fights and bull baiting as late as 1682."2 (vii) THE FORTUNE:- The building contract for the fortune given us the fullest details which we posses in regard to the construction of any Elizabethan 1 2 Collier, Life of Shakespeare, CC Xiii, C.W.Wallace, London Times, April 30May,1914. W.W. Greg; H.D. "66-68 for contract, henslowepaper, mun-149 theater. It was square measuring 80 feet each way on the outside; and 55 feet on the inside, the difference allowing for large galleries. The framework was wood, the foundations of brick, the three stories 12, 11 and 9 feet in height, the two upper stories overhanging ten inches and the galleries were 12 feet 6 inches in depth. Four divisions were made for the gentlemen's rooms and others for the two penny rooms but the locations are not specified. The galleries and rooms were provided with seats; the rooms had ceilings; and the homework of the whole interior was lathed and plastered. The galleries and stage were roofed with tiles, paled with oak and floored with deal. A shadow or heaven over the stage is not described; so we cannot tell whether it was supported by pillars or not. A tiring room was provided in the near of the stage, taking the place of the gallery and perhaps built out in the rear. The width of the stage is specified as 43 feet, and it extended to the middle of the yard - 27 1/2 feet deep to the gallery 40 feet to the rear wall. This gave a space in the pit of six feet between the stage and the gallery on other side. In all points unspecified the building was to be like the Globe; except that all the chief supports were to be square, "wrought pilaster wise with" carved proporeons called satiers"; referring probably ; to the pillars supporting the galleries. Alleyn's memorandum book states the expenses of the property as L240 for the lease, L520 for building the playhouse, L440 for obtaining freehold of the land, L120 for other buildings, making a total of L1320. The fortune was occupied immediately after its erection by the Lord Admiral's men, who became the Prince's men at the accession of Jamist and long continued one of the chief companies. On December 9, 1621, the fortune was burned. The new theater, completed in 1623, was round and of brick. Wilkinson reported that the building was still standing in the first years of the Kitain century; and published in his "Londina illustrater" a picture that has often been reproduced. But this cannot have any resemblance to the round fortune of 1623, though it is barely possible as Wilkinson asserted that portions of the galleries of the old playhouse were still recognizable in the interior of the building of 1811. In 1650, the people of St Giles petitioned for permission to use the dismantled theater as a place of worship, with that result we do not know. In 1661, the whole property was advertised for sale."1 (viii) THE RED BULL:- The Red Bull Theater was located in Clerken well on the upper end of St John's Street, but the exact state of its building is not known. There was a performance of a puppet show in St John's Street (on August 23, 1599) during which the house fell and two persons were killed; and there was some sort of a building perhaps an inn, known as the red Bull, prior to the building of the playhouse, for in that year, it was leased by the builder, Aaron Holland, to share holders, including some of the Queen's men. The patent to the Queen's men 1 Lawrence,William J.,"The Elizabethan playhouse and other studies, Shakespeare Head press, Stratford on AVON,1912 page- 157-158. dated 15, 1609, authorizes them to act "at their usual houses of the curtain and Red Bull". As the proceeding patent of 1603 mentions the Boar's Head Innyard as the second house it is probable that the Red Bull was built between 1603 and 1605 and first continued there. In 1633, it had, according to Prynne, been Lately, "reedefied and enlarged." The picture published in Kirkman's "wits" (1672) and often republished as "the interior of the Red Bull theater," has no authenticity". We learn from Howes that the Red Bull was a public theater; hence it was probably like the Globe and the Fortune in general construction. It sought patronage of more vulgar audiences than the Globe, Fortune, or the private theaters, and was the constant objects of girds at the vulgar and sensational character of its plays and acting. During the Protectorate there were varies attempts in 1648,49,54 and 55 to reopen this house. Inspite of orders commanding the offers to "pull down and demdish all stage galleries, seats, and Boxes, esected and used such stage plays", it survived until after the Destoration. According to wright's "Historia Historionica, the a king's players acted publicly at the Red Bull, after 1660; but by 1663, according to Davenant, "the house was standing open for fencing, no tenants but old spiders."1 In addition to those public playhouses which were not typical of the period, there were Sundry roofed in theatre called, for no clear reason, " Private". Such 1 Lawrence William J,. Old Theatre days and ways, George G Harrap and Co,Ltd., London, 1935. page-72. was black Friars. Shakespeare's troupe finally installed a "men's company" in the house in 1608.blackfriars had been converted from the original "great hall", assumed to be across one end of the narrow dimensions, since by this time, Italinate scenery was in use in court theatricals. It had benches for the whole audiences."1 Other private theatres were Whitefriars, salisbury court, the Phoenix in Drury have and the co-depit-in-court; the Lalter designed by Indigo Jones, used a permanent architectural setting in the Italian mode."2 1 Lawrence, William J., "Pre Restoration stage, Studies Harvard university press, Cambridge Mass 1927, Page-96. JONES, INIGO, Designs by Inigo Jones for Masques for the Walpole and Malone Societies, University press, Oxford 1924, Page - 185. 2 Evolution of the platform and tiring house: first level. Theatre(1576) and Globe(1599) plans compared. (From Adams, The Globe Playhouse. Courtesy of Dr. John Cranford Adams and Harvard University Press.) ARCHITECTURAL PLAN OF THE GLOBE: Globe stage met all the requirements of Shakespeare's theatrical performers persisted in Globe in a modified form. The major part of the acting area consisted of a platform stage jutting out into the auditorium round three sides of which the audience could gather. In the wall behind the stage, a certain number of spectators could be seated in balcony of the second level of the building. Later on this audience area, known as the lords-room was incorporated into acting area. The lords and upper society elite used to sit on the either side of the stage. The ground floor of this theatre was elongated, horse-shoe shaped constituted the auditorium with stage across the end. In case illusion became an indispensable element in dramatic presentation, then the less identity of actor was designed by make-up. This was realized in the classical theatre of Greek and Rome. This principle is responsible for the adoption of masks for the actors. But even then leading actor become an increasingly important figure in his own right. Today the star system actually publicizes the personal life, traits of character and idiosyncrasies of the personality of the leading actor foster in interest in the actor which far exceeds the role the actor plays. However for the need of certain amount of illusion there is a need to prevent the mingling of audience and actor in the theatre itself. Hence the stage doors were Evolution of tiring house: second level. theatre(1576), Rose(1592-1595), and …….(……-1599) plans compared. From Adams, The globe Playhouses. Courtesy of Dr. John Cranford Adams and Harvard University PRESS) carefully guarded and the audience were separated from stage by an arch pit. The doors of the auditorium were also helpful in collecting the entry money from the audience. In this way audience used to pass in a single file without creating any disturbance for the actors."1In the Globe 2 Burbage made two separate doors on the either side of auditorium for the exist of the audience and one more door at the back of the stage for the exist of the actors. Later on box-office was added to collect entry money. A visibility focal-length was kept in view for the audience who used to stand in a pit in front of the stage, for those who used to sit at the rear of the auditorium or in upper tiers. Consequently the level of the auditorium was raised for row-seaters. The side galleries of the in yards influenced Burbage. He constructed side galleries in the auditorium which offered greater safety and comfort to the audience. He made the auditorium multitier. The second gallery was added for nobility, while maintaining the visual focal length. The first gallery was two and a half feet above from the floor of the Hall. Hall space below gallery was called yard. "It is possible that in the yard itself the amphi-theatre survived in a modified form. It sloped down to the stage from all the three sides, thus allowing the gallery seaters to see above the heads of pennyseaters." 1 GILMAN, ROGER, Great styles of Interior Architecture with their Decoration and Furniture, Harper & Brothers , New York, 1924, Page-28. Reconstructed plan of the Globe: second level. (From Adams, The globe playhouses Courtesy of Dr. John Cranford Adams and Harvard University Press) The Theatre and then Globe were in octagonal from. This pattern was followed by Burbage to have more acting area, tiring rooms, as well as to accommodate the elite-audience in the circular galleries. Shakespeare preferred "Octagonal instead of quadrangular, and in this he was probably influenced by the amphi-theatres used for baiting of bulls and bears; but in the main his pattern was the inn-yards and the building that he erected as practically an inyard without the inn. The fact is that Burbage had seen and had studied every place of performance. He finalized the Globe keeping in view where the performers were comfortable and could perform smoothly. His design was a land mark in the art of theatre architecture which assimilated the ancient and the requisite contemporary theatre."19 Both Shakespeare and Burbage were unable to find adequate finances from the theatre. Therefore they jointed hands with leading actors of Lord Chamberlain's Company which, later, was known as King's Men and formed a syndicate. With smooth flow of finances the theatre was provided with all that which theatrical production demanded. Therefore Stages were made by constructing the Globe. The areas of Inner Stage, rear stage on the first level and the chamber on the second level were enlarged to accommodate scenes pertaining to wars, supernatural effects and storms. This area was doubted with better light and improved sight line. Now there was more space for realistic wall hangings, windows were added to the rear stage. It became easier to set climatic scenes. This unit of stage survived to modern age and has helped to point the way to the proscenium stage with its changeable Reconstructed plan of the Globe: third level. (From Adams, The Globe Playhouse Courtesy of Dr. john Cranford Adams and Harvard University Press.) settings. In the very next year If the completion of Globe an other theatre following its architecture came into being named Fortune. Stage: The first permanent stage was constructed in the theatre in 1576 and Later on with more provisions in the Globe in 1599. This stage 43 feet wide, 29 feet deep and 4 feet 5 inches in height. It was projected half way into the yard. Traps In Elizabethan theatrical productions machinery was used for raising and lowering demoniac personages. There was as many as five traps in platform stage, one in each of the four corners of the stage and the fifth was one long narrow trap at the rear or inner stage which could bear eight persons. There used to be usually noise while 'lowering' and 'raising' performers with the help of the machines. This noise was encountered with the help of 'music' or 'thunder' sounds. Traps exist in the modern British stage. Entrance – Exit doors and Background The first background of stage was used in Dionysus theatre. The background stage was a wooden Hut, which was later on replaced by decorated 'skene'. In the Elizabethan period Burbage was familiar with carved wood beautiful screen put on background of stage in the Inns of Court and the University Hall. This background had two doors one on each side known as stage doors. This pattern was adopted in the Globe. These doors are still in use of British and European stage. Curtained Alcove The scenes in medieval English plays were of two types. One localized, the specific just like a shop, house, place, court and the second unlocalized just as the road, street, grave-yard etc. These scenes were separated by curtains. Unlocalized scenes usually took place at the arc platform of the stage. The stage was closed from behind with curtains. The localized scenes were performed on the main stage with the help of curtain alcove, that space formed by setting of curtains. Generally localized scenes were performed at the middle stage with curtains. All parts of stage were covered with curtains. Even stage was divided into two parts with help of the curtains. The inner stage or any other part of the stage could be used alone or in combination. Each could be exposed to review, after having set in advance with distinctive properties and hangings behind closed curtains. It could be revealed again in different location. Here-in lay the means by which Shakespearean drama achieved its uninterrupted flow of action; when one group of actors brought a scene or sequence to its end at one stage unit, another group stood ready to pick up the action without pause in another unit, "the click of the completed rhyme of an exist tag was still audible, perhaps, as a new group took up its discourse."21 Inner Stage Inner stage was 20 to 25 feet wide, 10 to 21 feet deep and 12 feet high. This had two doors and one window. It was closer to the audience in galleries. It has curtained alcove. The inner and the front stage in combination was called double stage. The ballroom scenes in "Romeo and Juliet", " Much Ado About Nothing" and then trial scene in "The Merchant of Venice" were exhibited on this inner stage. In the floor of the inner stage there was a long narrow trap-door known as the 'grave' which could be used for ghosty apparitions rising besides beds. Sometimes it was used as vault or prison also. However this platform which was 12 feet high; therefore to save performers from an accidental fall "A guard rail was imperative to remind actors of the 12 foot drop to the platform below and to prevent their accidently falling off."22 Reconstructed plan of the Globe: Superstructure.(From Adams, The globe playhouses. Courtesy of Dr. John Cranford Adams and Harvard university Press ) Balcony Stage Action taking place of two or more levels, separately or simultaneously was provided on Greco-Roman stage. Three levels were also used in Church drama. There is a description of cycle-plays and pageant shows having "hell's mouth" on stage beneath an upper stage. In the Innyards the second floor with its gallery was above the back of the platform stage. The framework of the Elizabethan theatre with its three floor levels, which continued around the entire building, gave three levels to the background of the stage. It was since long that acting was performed on different stage levels. Balcony stage was frequently used in chronicle plays. It served to present 'castle', 'battles' 'city walls' and 'public buildings'. It was sometimes used as 'bedroom' and sometimes as 'prison' 'upper deck of ship', 'private room of "tavern" and 'upper halls of palace". The use of upper stage was stopped in Restoration period but again it has been revived in modern period in 1930s. These upper stages provide continuity to the action of the play. In "King Lear" action shifts between France and far off heathen lands. It was exhibited with the help of multi-tier stage. Sometimes one actor has to take part in two consecutive scenes. The scholars have marked it as law of Re-entry. This ensures that two sets will be ready on different stages. The same actor will quit first stage at least before the 10 – line dialogue is spoken in the previous scene and re-enters when just 10 lines are spoken in second set or the curtain is opened with appropriate music and sound effects. "If any character appears in two consecutive scenes which occur at places presumed to be at some distance from one another, he must, in order to make his remove seen in a scheme of dramatic time, either make his exist from the stage at least ten lines before the close of the earlier scene or delays his entrance to the later scene by at least ten lines. This law was seen when in "The Merchant in Venice" Portia and Nerissa re-enter after a change for court scene as Doctor of Law and his clerk."23 Window Stage The slanting sides of the Globe, having doors, permitted two other units in the acting area. These were by bay windows on the second level immediately over the doors. When these windows were open, one or two actors could stand in the bay and could be seen, down to the waist line at least. With curtains at the back, these days formed small stages in themselves. Jutting out above the doors and supported by slender columns, they formed penthouses or porches below, giving the effect of a very convincing house unit for such house as used in Jessica's elopement in "The Merchant of Venice". If the wing curtains on one side of the balcony stage were open, this window stage could then be a window-recess, extension of the balcony stage. The windows were used in balcony-bedroom scenes as in "Romeo and Juliet". The Tarras The Globe playhouse had four acting areas on the second level : a curtained inner stage, immediately below it lower stage, shallow balcony, window stages and rear stage. Shakespeare used the word Tarras (modern terrace) only once in stagedirection in "Henry VI" Act IV scene ix "Enter King, Queene and Somerset on the Tarras. "The tarras usually served to represent an elevated area out of doors. Its traditional and most frequent use was, of course, as the top of a defensive wall. It was so used by Shakespeare again and again, particularly in the early plays. Five times it served as castle or city walls in "Henry VI" once in "Titus Andonicus" "Richard II", "Coriolanus", "Timon of Athens" ............. Brutus and Marc Antony addressed the Roman populace ............ from Tarras."24 Gallery for Musicians The third level of the structured plan of the Globe carved yet another stage unit as Musicians' Gallery. It was tradition to place musicians and choristers high up on battements in castles. The highest place in the theatre then was obviously the place for the musicians, who, stationed in this small window gallery behind opaque curtains, could furnish the play with incidental music. John Cranford Adams has given a lovely description of Prespero "directing the actors and musicians in the apparition scene in the musicians' gallery to be not only theatrical effective, but most advantageous for the management of a very complicated scene. The music came from a point aloft but the musicians were unseen. Their concealment by curtains seems to have to been thought necessray both, because of a visible human source of celestial music would be dis-illusioning and inartistic, and secondly because they were "frequently called upon to descend singly or in groups to provide an incidental music or an accompaniment for songs in one of the lower stages as in "The Merchant of Venice" V(1), "Much Ado about Nothing" (iii) "Cymbeline" II (iii) "Othello" III (i), and "The Two Gentlemen of Verona" IV(ii)." The musicians usually moved down to a window-stage so that their music might be heard more clearly by the audience as well as by actors."25 2.4 Miscellaneous Stage Areas Weather conditions in open-air theatres have always been major problems as the audience and actors have to a be provided shelter against rain and sun. The ceiling line of the third level of the tiring house uptominstrel's gallery to half over the platform stage was a shelter for the actors known as "shadowe." This was supported by two stout pillars above. These pillars resembled marble columns. These pillars were sometimes painted in accordance with the locale of the play. The ceiling of the structure which would be visible from the below was often painted to resemble star-spangled sky. It was referred to as 'heaven.' The 'shadowe' was a tiring house for the actors. This was half-way down the platform stage and was sometimes used for entrance of the actors playing minor roles. Even cosmetics and costumes needed for immediate change were stored in this 'shadowe.' Huts Machinery for lowering of actors from above together with "clouds", "birds" had been a feature since earliest times. Such machinery, in order to maintain some essential dramatic illusion, was to be kept invisible, a superstructure was constructed above shadowe or tiring room. On this super-structure the hand worked heavy machinery was placed. Heavy properties were placed on the stage with such-machines. This machinery was covered under the "huts". Heavy properties included double throne, and huge beds. The huts also provided storage for sound-effect properties; for cannons and fire-works and battle properties. The hut was lowered upto the inner-stage and rarely at middle stage. One could stand on this super structure and used to sound trumpet to announce the commencement of the play. Hut seemed to have had two gables forming a wide spread 'M' like figure with two windows in each gable."26 Bell Tower View of the London" 1616 shows the Globe as having two rectangular 'huts' with a tower rising above them"16. This tower apart from being an excellent place on which to mount the flag-staff, also served to house one of the most effective properties used in Shakespeare's plays-the big bell whose tolling, clashing and chiming must have been heard across the Thames in the city itself. Property Room The backstage area of the Globe was very extensive. There was excavated "Hell", there were plenty of rooms as dressing rooms and property rooms. There was tiring house facade behind the gentleman's rooms on the first and second floors, and over the gentleman's rooms on the third floor."27 2.5 Staging Shakespeare's Plays John Cranford Adams has re-structured the plans of original Globe Playhouse. He has given all measurements of the stage and has studied where the scenes of various Shakespeare's dramas were performed. His study of "The Globe Playhouse " has been corroborated by the Joseph W. Scott the Technical Director of the Illini Theatre Guild, University of IIIinois. In accordance with it the facade of the stage is constructed in standard units. The fore-stage is extended out over the orchestra pit and the first rows of seats. When the action is performed on fore-stage the next scene if required is set on middle or rear stage. The standard setting of stage helps for quick setting of scenes. Each scene was set at the minimum cost so that the production proves commercially viable. Fore- Stage All unlocated scenes that take place in streets, on plains or in forests are played at fore-stage. Just as the scenes of "Henry VI" Act V scene 2-5, "As you Like It" Act III scenes 2-5 " Othello" Act 1 scene 2, were played on fore –stage. These scenes did not require any background. Only "supposedly" building is required around such scenes. Siloloquies were also delivered at Fore-stage. Middle Stage “The Taming of the Shrew” Act II scene 1 & III, “Hamlet” Act II (2) Act IV (3) were played on middle stage as the consecutive scene-setting was required. These are semi-located places such as court yards, inside of castle, front of the house. In addition to it back-ground was needed which was put as screen. Inner Stage In the scenes of battles, pageantry, crowds both inner and middle stages were used as in “ Romeo & Juliet” I (scene 3), II (scene 3) “ Henry VIII” II (Scene 3) and “ Much Ado About Nothing” Act I (Scene 2). Some of the interior scene requiring second floor like castles and palaces are exhibited on inner stage only. Balcony Stage Scenes played by one or more persons on the second level who talk to others standing below will use window stage or balcony stage “Romeo and Juliet” Act III (Scene 5)IV (scene 3) “ Hamlet” Act III (scene 4) Tarras Stage All out-of- door scenes that occur at an elevation on city walls, on bettlements, or in an ante-chamber adjacent to an upstair apartments; take place on tarras. “Winter‟s Tale” Act II (scene 2), “Richard III” Act III (scene 5) and all scenes and on city walls and battlements take place on Tarras Stage. To manage the more complicated scenes several times the combined stages were used. The flow of action continued uninterrupted and secondly more space was available to the actors. Middle and Fore-Stage “ The Merchant of Venice” Act IV (scene 1), “ The Winter‟s Tale” III (scene 2), “Othello” Act 1(scene 3) “A Mid Summer Night‟s Dream” Act 1(scene 1). Middle and Inner Stage “The Merchant of Venice” Act II (scene 7,9) “A Mid Summer Night‟s Dream” Act II (scene 2). Middle and Balcony Stage “Rome and Juliet” IV (scene 5). The Nurse, by Julie‟s bed on the balcony, was joined by Copulet and Lady Copulet. Friar Lawrence and paris arrive below and then go up to the balcony, leaving peter and the Musicians belo “Antony and Cleopatra” Act IV (scene 4, 13), “Hamlet” Act III (scene 1). Middle Stage and Tarras The demarcation and use of such stage helps a production: one; action is uninterrupted; two; complicated scenes are managed easily and the theatrical action flows smoothly; three, aesthetic fitness of the scene is maintained; four, more space is available for acting area, audibility and visibility remains proper and adequate. Flow of music in all directions is spontaneous."28 THE PHYSICAL STAGE Plan of the lower stage, showing also the relative posi-tion of the “hut” and shade. Broken lines indicate the “hut,” dotted lines the shade, and waved lines the curtain. jj are the stage posts, xx the proscenium doors, dce the curtain, yyyy the „„wings,‟‟ higedf the outer stage, deut the inner, rjjs the „„hut,‟‟ and jopj the shade. The distance from h to i is 15 feet, f to g 39 feet, GROUND PLAN OF A SHAKESPEAREAN STAGE a to c 26 5/6 feet, j to j 20 feet, j to o 6 feet, j to r 20 feet, d to e 25 feet, and b to c 10 feet. 1. Plan of the upper stage, showing also the relative posi-tion of the projecting „„hut‟‟ and shade. The line marking is the same as in I. ww are the balcony window, deut the gallery, dce the gallery curtain, and zz the gallery doors. The distance from d to e is 25 feet, and d to t 10 feet. Plan of the „„heavens.‟‟ This represents one plane formed by the base of the „„hut ‟‟ and the ceiling of the gallery and shade. The broken line indicates the connection of the „„hut‟‟ and shade, and the waved line the suspended gallery curtain. The dimensions of the „„hut‟‟ and shade been given in I, and the gallery in II."29 MINOR FEATURES OF THE STAGE The various minor features of the stage may be enumerated. (1).The proscenium doors must have varied somewhat in their position in the different theatres; thus existence is inferred from the numerous stage directions which make it clear that they must have been placed on either side of curtain. (2)The windows and balconies over the doors are not shown in any picture, but their existence is suggested by many scenes, especially in seventeenth century plays, A person in one of these balconies could see the inner stage, or be seen from it. Moreover, the person so located would be clearly visible to the spectators in the theatre. These windows over the doors consequently proved more serviceable than the rear balcony. (3) The balcony at the rear, over the inner stage, seems to have been less used in later than in earlier plays, and it appears in Restoration. In the earlier plays, it appears frequently as the wall of the city or tower; but when not required by the action of the play it seems to have been used for spectators or perhaps musicians. (4) The hut shown in the drawings of exteriors of the public theatres must have been replaced by an upper room in the private theatres. In all spectacular plays there is a good deal of ascending and descending, and the upper room or hut will be frequently employed. (5) Trapdoors seems to have been located in several places in the front stage, on the inner stage and in the balcony. (6) Besides, the main curtains, others were employed for specific purposes, the gallery was curtained and used as a place of concealment; beds were provided with curtains, finally, there were occasionally traverses, or curtains running at right angles with the rear of the stage. (7) Of the dressing or tiring room, little is known small space was required in comparison with a modern theatre; but it seems probable that in the later private houses more room was provided than is indicated in our diagram. From the terms of the contracts, one might suspect an addition in the rear of the stage of the fortune and hope."30 A few other details may complete the picture. The pit was without seats in the public theatre, but was provided with benches in BlackFriars and the later indoor theatres. The floor was not build on an incline, so far as we know, although possibly. The later theatres may have had sloping stages, as did some of the Masques. The private as well as the public theatres had galleries. Foot lights were not used, but in the private theatres the artificial lights was then considered brilliant. The candles were of wax."31 STAGE PRESENTATION The outer stage, with the curtains closed, was without scenery, settings, or properties, and was used for unlocalized scenes. Not only scenes in a street, open place, or before a house could be represented here, but any kind of place in which there no properties re-quired, or else where they were so few and simple that they could be easily brought on and off. The inner stage, shut off by the rear curtain, was used for definitely localized scenes requiring heavy properties. When the curtains were drawn, the setting, e.g. for temple, shop, bedroom, or forest, was disclosed at the rear. If the inner stage represented a temple or shop, the outer stage became a place before the temple or shop; if the inner stage was occupied by a bench with judges or a throne for the king, the outer stage became court-room, or presence chamber. If the inner was bedroom, the outer became a hall or anteroom. Indeed, any exact separation of the two stages became impossible, when the curtains were once opened. The inner stage then became an integral part of the outer stage, or rather the outer stage now embraced the inner."32 Action was by no means necessarily confined to the inner stage, and might readily overrun its boundaries, inevitably seeking the front of the stage If the scene was a bedroom, the whole stage might be regarded as the bedroom; if a forest, the trees and banks set in the rear stage served to convert the whole inner-outer stage into a forest. The inner stage, while it might serve for a specific and limited space as a cave, shop, cell, might also serve as a sort of back-ground for the outer stage. Doors to right and left of the inner stage served for entrances and exits to the other stage, and could be regarded as entrances to houses, cities, prisons, or whatever places might be imagined within. There were also entrances to the inner stage, so that persons or properties might be brought on and off without traversing the outer plat-form. Over the inner stage was fa balcony- in some cases hung with curtains, and serving to indicate any localized place above the level of the main stage, - tower,city walls, upper room etc. Over the doors there were windows or balcony. as windows of houses. The hut above and various trapdoors in the floors of the , main stage, inner stage. and balcony, were chiefly used in spectacular plays requiring gods, devils, and transformations."33 THE PROBLEM OF THE INNER-OUTER STAGE The chief problem in understanding Elizabethan staging is that of the outerinner stage. It is here that the English professional stage developed a procedure different from those on the continent. In Paris, when the professional actors came to succeed the confreres at the Hotel Bourgogne, they continued the methods and even some of the sets of that stage, thus adopting a simplified from of the simultaneous setting. Curtains might be used to conceal or discover properties but the stage would usually provide for a number of different localities, as e. g. a bedchamber, a fortress by the sea, a cemetery, a shop In Spain the simultaneous set did not continue in the public theaters, which presented a bare stage. Curtains were here employed to conceal and discover properties in rear ; but the fact that the stages of Madrid and Seville were recesses and not projections would seem to have prevented such a development of the inner stage for a background as took place on the projecting platform in London."34 No one now thinks that the English stage had a system of multiple setting like that of the Hotel de Bourgogne, although students differ as to the extent to which multiple sets were used on the London stage. was merely a bare platform: every one admits the existence of a curtained inner stage. On the issue, however, of the use of this inner stage, scholars have differed diametrically, and even now, after years of investigation and discussion. little has been done to harmonize the two opposing theories. Each of these theories is based on unquestioned facts of stage presentation, and can be supported by much evidence and argument, and both in their extreme form are demonstrably wrong and incosistent with general practice. One group of scholars has emphasized the importance of the bare outer stage and minimized the employment of the inner stage They have insisted on the rapid changing of scene, the absence of properties, the incongruity of setting. They have found plays where the scene changes with actors on the stage, where faustus before the eyes of the audience passes at once from his study to a pleasant green; and others where several places seem represented at once. They have found other plays where the scene chaches from forest to palace and then to street, and then back to forest, and have inferred that trees and other necssary properties of the forest remained before the spectators' eyes all of the time. They gave in consequence celed Shakespeare's stage medieval, plastic, symboic, incongruous, and they have elevated its occasional incongruity into a sort of principle of procedure. The opposing theory or attitude has rightly made much of the inner stage as a place for setting properties and indicating a change of scene by drawing and closing the curtains; but it has tended to exaggerate the usefulness of this part of the stage and its followers have exeted the change or alternation of sanes from outer to inner stage into a fixed procedure of staging. They have indeed made it a principle of dramatic composition and imagined the dramatists constructing their plays as series of alt series of the alternating inner and outer scenes. The use of the inner stage must be discussed at length in this chapter, but it may be remarked at the start, that the alternation theory is not only without sufficient evidence, but rests on the mis-conception that a large minority of scenes in Eliza-bethan drama were definitely localized either on the stage or in the mind of their authors. THE EVIDENCE FOR METHODS OF STAGING The plays are rarely divide into acts, and still more rarely into scenes, except by an „„exeunt omnes.‟‟ On the modern stage, the fall of curtair makes plain the division between scenes and marks an interval for an imaginary change of place or time. Or the Elizabethan stage, this break is indicated merely by an empty stage. Yet the scene is a manifest unit in the constriction. In the early days, a single scene sometimes covers a long lapse of time and moves from place to place. But as the technic grows more certain, a scene is confined to one place and an interval of time not much longer than the action. Lapses of time and changes of place are to be imagined in the intervals between the scenes. Indeed if a lapse of time is indicated, the persons who exeunt at the close of the scene rarely return immediately to the stage on the beginning of the next scene. A speech or even a scene intervenes before their reentry. This practice, which has been formulated by Prolss into a law, has various exceptions, out is a natural result of an effort clarity in con-struction. There is, however, no tendency to limit the number of scenes. Sometimes a scene occupies an entire act, and in authors seeking to approximate to the unities of time and place, the number of scenes is reduced; but in general a single play includes many scenes. And there is no running on of scenes, except in so far as this is accomplished by use of the inner stage."37 Is announced as „„a room in the palace‟‟ or „„the sea-shore,‟‟ and one accepts the designation in spite of oneself. A great number of scenes are not localized in any way whatever. There is no indication where the actors are, how they came, or in what way they will depart. They may be indoors or outdoors, on a ship or in the air, for anything that the text discloses. A second class of scenes is only vaguely localized. They require no properties, offer no business that will give us a clue, but we infer by the conversation or action that they are in the neighborhood of the palace or else within it, or that they are on a street or that they are within doors. The distinction between outdoor and indoor scenes is rarely certain unless some properties are introduced."38 Scenery, lightening, Properties: There was certain amount of built and painted scenery, flat and three dimensional pieces on the Elizabethan Stage, but the scenery used at it had been in the medieval period, rather than it is in modern times. The frame stage, which is entirely concealed by a front curtain when the curtain is drawn up, it as if the wall of a room has been removed, allowing us an intimate view of the going on inside. The scenery in the modern theatre usually represented a definite place at a definite time, a scene change being a major operation accomplished behind a lowered curtain. the Elizabethan theatre, like the medieval, had no front curtain and the platform stage was unlocalized; this is it was neutral ground that night represent a public square, a forest, a street, or a seacoast, in rapid succession. this feat was performed by a stagehand who, in full view of the audience carried on and off such simple set pieces and properties as a rock, a tree, or a gate. In addition to these significant and movable items, the lines of the play would indicate the localand the time of day or night at the opening of each scene it was up to the audience to exercise its imagination and supply the missing details in the décor. On this type of stage, different times and places could. Succeed each other as rapidly as stagehands and actors came and went."39 The inner stage and the chamber above it were curtained off, as has been said so that it was possible for these areas to be furnished to represent definite places- a bedroom, a prison, or a throne room. Painted canvas or tapestries were hung in the alcoves to help suggest locale; if a tragedy was being performed, taperies were black. Very often the inner stage and the platform were combined into single set; the curtain would open and disclose, for instance, that the inner stage was a throne room-king and queen would be seated on a two large guilded chairs and courtiers stood about. As the scene progressed, the actors would move out of the alcove on to the platform, thus giving the Elizabethan stage enormous flexibility, Variety and interest."40 The Elizabethan play took two and one half to three hours to perform and was presented in the afternoon from three to six in the summer and from two to fifth in the winter. In this open air theatre, general illumination was provided by natural daylight; the platform always had enough light upon it and even the alcoves, under the "heavens", were amply lit. But many scenes were supposed to take place at night or in the darknessof the caves and cells and this provided the opportunity for the use of torches, cressets, candles, and Lanterns. Macbeth, which was called in its entirely "a thing of night", has scene after scene in which special lightning is obligatory; cressets affixed to walls to cast flickering lights on bloody daggers or bloody hands. Sad fluttering candles for the sleep walking scene and lurid, miasmic flames for the cauldron of the witches. The fact that of all these things were going on in broad daylight did not dislurts the Elizabethan spectators. It was one of the conventions of his theatre which he accepted. There were innumerable hand properties- daggers and swords, fans, hander kerchief globlets, musical instruments, and in the senecan melodramas such as Titus Andronicus, several Heads and hands- but all of these freshly strewn for the text."41 THE ACTORS: Three classes of persons were connected with the theatres, sharers, hirelings and servants. The 'Sharers' were the most important actors, who actually made up the "company" and who divided among themselves. the money taken in each day at the door; according to their importance some received whole shares, others half shares. The "hirings" were actors of lower rank who did not share in the large profits of the theatre but were engaged by the company at a fixed and rather small salary. The "servants" were employed by the company as prompters, stagehands, property keepers, money gathers and caretakers of the buildings ."42 The actor in the Elizabethan theatre were all male, women were not permitted to appear upon the stage. The stage parts of young women were played by boys , those of old women or of hags, like the witches in Macbeth, were built, a travelling company of players would consist of four or five men and one or two boys. The plays often contained as many as twenty or thirty characters, so that each actor was required to play several parts. This produce of developed into a high art in Shakespeare's company, which at its peak employed only twelve men and six boys. Yet the cast of Macbeth less twenty eight characters and requires, in Addition, Apparitions, Lords, Gentleman Officers, Soldiers, Murderers, Attendants and Messengers. An analysis of the play will show that only Macbeth and Lady Macbeth while the other characters make brief appearance. Each actor in Shakespeare's company, particularly the stars or sharers, had his specialty."43 Richard Burbage was the leading man; he created the roles of Richard III, Romeo, Hamlet, Othello, Macbeth, and King Lear; Will Kempe, a low comedian, played such parts as Dogberry in Much Ado about Nothing and Bow tom in A Midsummer Night‟s Dream; his place in the company was later taken by a more subtle and refined comedian, Robert Armin, who acted the First Grave digger in Hamlet and the Fool in King Lear; John Heminges specialized in old men: Polonius in Hamlet and Brabantio in Othello; while Augustine Phillips and Thomas Pope may have played the fickle lovers or the bragging soldiers. The actors were trained, as in other Elizabethan professions, under an apprenticeship system. A boy would start at the age of ten and be required to pay a sum of money to the master for whom he would work for seven years without receiving a salary; in return he would be given board and lodging and taught his trade thoroughly. The experienced actor would teach the boy in his care to play women‟s parts and also the type of part in which the older actor specialized that his apprentice mighty become his successor. It is believed that the boys we hired in pairs; two who were about ten years of age, two about twelve to for teen, and two between fifteen and eighteen. The eldest would serve as leading ladies as long as their voices and bodily development allowed, then they would graduate into adult roles, at which point a new pair of ten -year-olds would be taken on. An effort would be made to select a serious, blond, blue-eyed boy along with a boy who was small and dark for comedy; these types are paired in man of Shakespeare‟s plays. Some of these boys, such as Nathaniel Field and Richard Robirson, went on to become celebrated actors and writers and sharers in the company. Sir Laurence Olivier, in modern times, began his acting career at fifteen by playing Katharine in The Taming of the Shrew at Stratford on Aven . In acting the women‟s parts, the boy played with great simplicity, directness and restraint; Shakespeare, in fact, underemphasized sex in these roles. In man of the comedies, furthermore, the heroines disguised themselves as boys. It is more difficult of attempt to describe the acting style of the adults it could not have been as naturalistic as that of our own day, principally became the dialogue was dialogue was written in verse. It must to some extent have been stylized and declamatory, although we know from Hamlet‟s advice to the Players that shakespeare deplored ranting and bombast and broad, empty gestures. We deduce from Hamlet‟s speech the following set of rules for the actor: The speeches we to be spoken rapidly but intelligibly; the body movements and gestures were to be natural; the energy and emotions were to be under control at all times the actor was to identify himself closely not only with the character he was plays but also with the customs and conventions of his day; and finally, the actor ...cot to play down to his audience and be satisfied with cheap effects, but was to ......for the approval of the serious and discerning playgoer, rare as he might be . COSTUMES All Elizabethan plays were done, so to speak, in modern dress; that is, the costumer of the actors were the last word in contemporary fashion, The women wore wide spreading Farthingale of satin, velvet, taffeta, cloth of gold, silver ,copper, and the ruff of stiff lawn. The persons was ornamented with gold and silver jewelry, precious stones, and strings of pearls. The men wore doublet and hose made of rich and contrasting materials, trimmed with lace of gold, silver, or thread; the jacket and cloak were made of silk or velvet; the ruffs, of stiff lawn the shoes of fine, soft leather; and the outer robes were heavily furred. the actors, like the fops and ladies of the period, were also interested in the high styles of foreign countries and so appeared in German trunks, French hose, Spanish hats, and Italian cloaks confusingly mixed. The satirists of the day ridiculed these fashions, and clowns appeared on the stage in exaggerated paro-dies of then. In The Merchant of Venice (I, 2), Portia remarks of a young English nobleman: „„How oddly he is suited! I think he bought his doublet in Italy, his round hose in france, „bonnet in Germany. . . .‟‟ The colors too were dazzling and symbolic. One gown was white, gold, silver, red, and green another was black, purple, crimson, and white; and there were dresses of such delicate tines as coral pink, silver, and gray. These, among many others, were the colors of the nobility and the courtiers, while servants were limited to dark blue or mustard-colored garments. Green sleeves, which became celebrated in song, were the mark of the courtesan. In addition to their secular garments, the actors wore elaborate robes of state, impressive ecclesiasteal vestments, the various military and civic uniforms of the day. Elizabethan stage costumes were undoubtedly magnificent and costly; they represented, in fact, the most expensive item in the production budget. One producer paid a dramatist 8 pounds for a play, then spent 20 pounds on a gown for the leading lady; another garment cost more than spent theater took in a week. But there was obviously a need for this spectacular display to offset the paucity of scenery and satisfy the demand of the audience for eye-filling splendor and pageantry. It did not in the least disturb the playgoer that Timon of Athens, Julius Caesar of Rome, and Cleopatra of Egypt all wore Elizabethan costumes. Nor did he appear to be bothered by the fact that ancient and contemporary costumes were worn side by side, a man in medieval armor talking to one in a fashionable dou-blet, with the occasional intermixture such foreign items as a Moor‟s robe, a Turkish turban,or Shylock‟s Jewish gaberdine.‟‟ No attempt was made to achieve complete historical accuracy of costume until the nineteenth century. A number of fantastic costumes were in for fairies, devils, and clowns, but these were patterned mainly on traditional representations which had come down from the medieval mystery and miracle plays, The devils wore tails, cloven hoofs, and horns, the clowns were dressed like country yokels or wore the red and yellow motley of the fool; ghosts usually wore sheets, though that of Hamlet‟s father appeared in full armor; the witches in Macbeth wore ugly masks and fright wigs. The costumes were acquired in various ways and might belong to the company jointly or to the individual actors. Some new garments were bought but these were so expensive as to be almost prohibitive; an effort was therefore made to get hold of secondhand clothing. Many courtiers, either because they were in need or because they did not wish to be seen too frequently in the same outfits, sold their finery to the players. Upon the deaths of some noblemen them in turn to the actors. After the death of Mary of Scotland her wardrobe was turned over to Queen Elizabeth who presented these beautiful gowns to actors in lieu of a fee. if a theatrical company failed, its costumes were sold to active competitors. Some theater owners rented their costumes to other companies; and each company had at least one or two tailors in regular employ who busily altered or renovated the costumes on hand. We may gain some notion of the magnitude of the problem faced in costuming the players when we realize that successful companies produced as forty plays in a season. MUSIC AND DANCE The Elizabethan age was a highly musical one; instrumental and vocal music in solo or concert enlivened all public and private occasions. The Elizabethan play was accompanied almost throughout by music that either served an integral dramatic purpose or was merely incidental to the action. There were four basic types of music used in the plays: military and ceremonial music, songs sung either with or without instrumental accompaniment, incidental instrumental music played as an accompaniment to dancing, action, or speech, and unmotivated background music used to create a special mood or atmosphere. In addition, many sound effects were employed to heighten the aural appeal of he plays by arousing tensions and simulating reality. In A Midsummer Night‟s Dream, the musicians may actually have appeared on the stage, but usually the music emanated from the Music Room on the second gallery above the stage. The military and ceremonial music was used most frequently in the chronicle history plays, but was also employed in the tragedies. Such directions in the text as „„alarums and excursions‟‟ called for the .......of trumpets, cymbals, and roll of drums. Charges and retreats .............,as did fanfares or flourishes which announeed the entry of royal or noble persons. The hautboy, forerunner of the oboe, was another instrument much used in military scenes. Many songs found their way into the plays. Shakespeare composed a number of original ones; others were popular songs of the day, or old traditional airs. The clown Feste, in Twelfth Night, sings an ancient ballad „„Come Away, Death‟‟ accompanied by instrumentalists who are on stage. But the old drinking song, „„And let me the canikin clink,‟‟ sung in the tavern scene in Othello, was unaccompanied except by the banging of tankards. From the Music Room came the background, or „„still,‟‟ music, as it was eailed which helped to intensify the terrifying atmosphere and eerie mood of the Ap-parition and Witch scenes in Macbeth. A thunderclap is heard as each Apparition appears and his passage across the stage must been accompanied by strange unearthly sound; the dance of the witches, too which was frenzied and frightening most have done to music. Sound effects were closely related to musical effectsand were frequently called thunder plays. Thunder, the clashing of metal and clanking of chains, the tolling of bells and winding of hunding horns are only a few of the sounds which the Elizabethan stagehands had to produce. Dancin000.g like music, was immensely popular in the social life of the time and palyed an equally dances were the allemande, the courate, the galliard,, the lavolta and the pavan; while the most celebrated country dances were sellenger's round and the Hay. Each dance , had its own traditional music. Many of the comedies ended with the playing of these advance the plots of the serious plays. Shakespeare