* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Physiological bases of behavior emotions

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

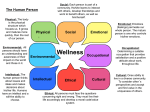

Physiological bases of behavior: emotions Emotion • Emotion is a reaction, both psychological and physical, subjectively experienced as strong feelings, many of which prepare the body for immediate action. • In contrast to moods, which are generally longerlasting, emotions are transitory, with relatively well-defined beginnings and endings. They also have valence, meaning that they are either positive or negative. • Subjectively, emotions are experienced as passive phenomena. Emotional experience • Areas of the brain that play an important role in the production of emotions include the reticular formation, the limbic system, and the cerebral cortex. Nervous structures and emotional reactions • The reticular formation, within the brain stem, receives and filters sensory information before passing it on the limbic system and cortex. The reticular formation • The limbic system includes the hypothalamus, which produces most of the peripheral responses to emotion through its control of the endocrine and autonomic nervous systems; the amygdala, the hippocampus; and parts of the thalamus. • The frontal lobes of the cerebral cortex receive nerve impulses from the thalamus and play an active role in the experience and expression of emotions. The limbic system The brain and emotional learning • The amygdala, a structure of the limbic system (the behavioral center of the brain) located near the brainstem, is thought to be responsible for emotional learning and emotional memory. • Studies have shown that damage to the amygdala can impair the ability to judge fear and other emotions in facial expressions (to “read” the emotions of others), a skill which is critical to effective social interaction. The amygdala serves as an emotional scrapbook that the brain refers to in interpreting and reacting to new experiences. It is also associated with emotional arousal. The prefrontal cortex • The ability to understand the thoughts and feelings of others is also regulated by the prefrontal cortex of the brain, sometimes called “the executive center.” This brain structure and its components store emotional memories that an individual draws on when interacting socially. • Research studies have demonstrated that individuals with brain lesions in the prefrontal cortex area have difficulties in social interactions and problem-solving and tend to make poor choices, probably because they have lost the ability to access past experiences and emotions. The physiological changes associated with emotions • While the physiological changes associated with emotions are triggered by the brain, they are carried out by the endocrine and autonomic nervous systems. • In response to fear or anger, for example, the brain signals the pituitary gland to release a hormone called ACTH, which in turn causes the adrenal glands to secrete cortisol, another hormone that triggers what is known as the fight-or-flight response, a combination of physical changes that prepare the body for action in dangerous situations. The autonomic response to emotional excitation • The heart beats faster, respiration is more rapid, the liver releases glucose into the bloodstream to supply added energy, fuels are mobilized from the body’s stored fat, and the body generally goes into a state of high arousal. The pupils dilate, perspiration increases while secretion of saliva and mucous decreases, hairs on the body become erect, causing “goose pimples,” and the digestive system slows down as blood is diverted to the brain and skeletal muscles. • These changes are carried out with the aid of the sympathetic nervous system, one of two divisions of the autonomic nervous system. When the crisis is over, the parasympathetic nervous system, which conserves the body’s energy and resources, returns things to their normal state. Autonomic reaction to ideferent information Autonomic reaction to important information Ways of expressing emotions • Ways of expressing emotion may be either innate or culturally acquired. Certain facial expressions, such as smiling, have been found to be universal, even among blind persons, who have no means of imitating them. Other expressions vary across cultures. • In addition to the ways of communicating various emotions, people within a culture also learn certain unwritten codes governing emotional expression itself—what emotions can be openly expressed and under what circumstances. Cultural forces also influence how people describe and categorize what they are feeling. • An emotion that is commonly recognized in one society may be subsumed under another emotion in a different one. Some cultures, for example, do not distinguish between anger and sadness. Tahitians, who have no word for either sadness or guilt, have 46 words for various types of anger. Importance of emotions for bechavior • In daily life, emotional arousal may have beneficial or disruptive effects, depending on the situation and the intensity of the emotion. Moderate levels of arousal increase efficiency levels by making people more alert. • However, intense emotions—either positive or egative— interfere with performance because central nervous system responses are channeled in too many directions at once. The effects of arousal on performance also depend on the difficulty of the task at hand; emotions interfere less with simple tasks than with more complicated ones. Negative emotions Emotional intelligence • Emotional intelligence is the ability to perceive and constructively act on both one’s own emotions and the feelings of others. • Emotional intelligence (EI) is sometimes referred to as emotional quotient or emotional literacy. Individuals with emotional intelligence are able to relate to others with compassion and empathy, have well-developed social skills, and use this emotional awareness to direct their actions and behavior. Applications • The concept of emotional intelligence has found a number of different applications outside of the psychological research and therapy arenas. • Professional, educational, and community institutions have integrated different aspects of the emotional intelligence philosophy into their organizations to promote more productive working relationships, better outcomes, and enhanced personal satisfaction. • In the workplace and in other organizational settings, the concept of emotional intelligence has spawned an entire industry of EI consultants, testing materials, and workshops. The four areas of emotional intelligence, as identified by Mayer and Salovey, are as follows: • Identifying emotions. The ability to recognize one’s own feelings and the feelings of those around them. • Using emotions. The ability to access an emotion and reason with it (use it to assist thought and decisions). • Understanding emotions. Emotional knowledge; the ability to identify and comprehend what Mayer and Salovey term “emotional chains”—the transition of one emotion to another. • Managing emotions. The ability to self-regulate emotions and manage them in others. Tests or assessments • A number of tests or assessments have been developed to “measure” emotional intelligence, although their validity is questioned by some researchers. • These include the Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test (MSCEIT), the Multifactor Emotional Intelligence Scale (MEIS), the Emotional Competence Inventory 360 (ECI 360), the Work Profile Questionnaire-emotional intelligence version (WPQ-ei), and the Baron Emotional Quotient Inventory (EQ-i). Other psychometric measures, or tests, such as the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, Revised (WISC-R), a standard intelligence test, are sometimes useful in measuring the social aptitude features of emotional intelligence. Emotional development • Emotional development is the process by which infants and children begin developing the capacity to experience, express, and interpret emotions. • To formulate theories about the development of human emotions, researchers focus on observable display of emotion, such as facial expressions and public behavior. Emotional development • Between six and ten weeks, a social smile emerges, usually accompanied by other pleasureindicative actions and sounds, including cooing and mouthing. • During the last half of the first year, infants begin expressing fear, disgust, and anger because of the maturation of cognitive abilities. • Caregivers supply infants with a secure base from which to explore their world. • During the second year, infants express emotions of shame or embarrassment and pride. During this stage of development, toddlers acquire language and are learning to verbally express their feelings. This ability, is the first step in the development of emotional self-regulation skills. Toddlerhood (1-2 years) Emotional expressivity • In toddlerhood,children begin to develop skills to regulate their emotions with the emergence of language providing an important tool to assist in this process. • Empathy, a complex emotional response to a situation, also appears in toddlerhood, usually by age two. • The development of empathy requires that children read others’ emotional cues, understand that other people are entities distinct from themselves, and take the respective of another person (put themselves in the position of another). Preschool (3-6 years) Emotional expressivity • Parents help preschoolers acquire skills to cope with negative emotional states by teaching and modeling use of verbal reasoning and explanation. • Beginning at about age four, children acquire the ability to alter their emotional expressions. For example, in Western culture, we teach children that they should smile and say thankyou when receiving a gift, even if they really do not like the present. • It is thought that in the preschool years, parents are the primary socializing force, teaching appropriate emotional expression in children. Middle childhood (7-11 years) • Children ages seven to eleven display a wider variety of self-regulation skills. Sophistication in understanding and enacting cultural display rules has increased dramatically by this stage, such that by now children begin to know when to control emotional expressivity as well as have a sufficient repertoire of behavioral regulation skills allowing them to effectively mask emotions in socially appropriate ways. • During middle childhood, children begin to understand that the emotional states of others are not as simple as they imagined in earlier years, and that they are often the result of complex causes, some of which are not externally obvious. Adolescence (12-18 years) • Adolescents have become sophisticated at regulating their emotions. They have developed a wide vocabulary with which to discuss, and thus influence, emotional states of themselves and others. • Research in this area has found that in early adolescence, children begin breaking the emotionally intimate ties with their parents and begin forming them with peers. Another factor that plays a significant role in the ways adolescents regulate emotional displays is their heightened sensitivity to others’ evaluations of them, a sensitivity which can result in acute selfawareness and self-consciousness as they try to blend into the dominant social structure. Coping With Stress CBS News Online • http://www.cbsnews.com/secti ons/i_video/main500251.shtml? id=2379111n • Coping With Stress CBS News Online • How Your Brain Handles Stress Stress • Stress is the physiological and psychological responses to situations or events that disturb the equilibrium of an organism. • Stress results when demands placed on an organism cause unusual physical, psychological, or emotional responses. In humans, stress originates from a multitude of sources and causes a wide variety of responses, both positive and negative. • Despite its negative connotation, many experts believe some level of stress is essential for wellbeing and mental health. Person’s needs Stressors • Stressors—events or situations that cause stress— can range from everyday hassles such as traffic jams to chronic sources such as the threat of nuclear war or overpopulation. • Much research has studied how people respond to the stresses of major life changes. The Life Events Scale lists these events as the top ten stressors: death of spouse, divorce, marital separation, jail term, death of close family member, personal injury or illness, marriage, loss of job through firing, marital reconciliation, and retirement. • It is obvious from this list that even good things—marriage, retirement, and marital reconciliation— can cause substantial stress. Fazes of stress reaction TOP TEN STRESSFUL EVENTS • • • • • • • • • • Death of spouse Divorce Marital separation Jail term or death of close family member Personal injury or illness Marriage Loss of job due to termination Marital reconciliation or retirement Pregnancy Change in financial state Reactions to stress • Reactions to stress vary by individual and the perceived threat presented by it. • Psychological responses may include cognitive impairment—as in test anxiety, feelings of anxiety, anger, apathy, depression, and aggression. • Behavioral responses may include a change in eating or drinking habits. • The “fight or flight” response involves a complex pattern of innate responses that occur in reaction to emergency situations. The body prepares to handle the emergency by releasing extra sugar for quick energy; heart rate, blood pressure, and breathing increase; muscles tense; infection-preventing systems activate; and hormones are secreted to assist in garnering energy. The hypothalamus, often called the stress center of the brain, controls these emergency responses to perceived lifethreatening situations. Stress and pathology • A relatively new area of behavioral medicine, psychoimmunology, has been developed to study how the body’s immune system is affected by psychological causes like stress. • While it is widely recognized that heart disease and ulcers may result from excess stress, psychoimmunologists believe many other types of illness also result from impaired immune capabilities due to stress. Cancer, allergies, and arthritis all may result from the body’s weakened ability to defend itself because of stress. Coping with stress • Coping with stress is a subject of great interest and is the subject of many popular books and media coverage. • One method focuses on eliminating or mitigating the effects of the stressor itself. For example, people who experience extreme stress when they encounter daily traffic jams along their route to work may decide to change their route to avoid the traffic, or change their schedule to less busy hours. • Instead of trying to modify their response to the stressor, they attempt to alleviate the problem itself. Generally, this problem-focused strategy is considered the most effective way to battle stress. Biological feedback for coping stress Emotion-focused methods • Another method, dealing with the effects of the stressor, is used most often in cases in which the stress is serious and difficult to change. Major illnesses, deaths, and catastrophes like hurricanes or airplane crashes cannot be changed, so people use emotion-focused methods in their attempts to cope. Examples of emotion-focused coping include exercise, drinking, and seeking support from emotional confidants. • Defense mechanisms are unconscious coping methods that help to bury, but not cure, the stress. Sigmund Freud considered repression— pushing the source of stress to the unconscious— one way of coping with stress. Rationalization and denial are other common emotional responses to stress. Discovering of stress in experiment