* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Baron de Montesquieu (1689

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

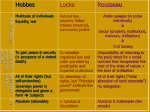

Jean Jacques Rousseau 1712-1778 Themes, Arguments, and Ideas The Necessity of Freedom In his work, Rousseau addresses freedom more than any other problem of political philosophy and aims to explain how man in the state of nature is blessed with an enviable total freedom. This freedom is total for two reasons. First, natural man is physically free because he is not constrained by a repressive state apparatus or dominated by his fellow men. Second, he is psychologically and spiritually free because he is not enslaved to any of the artificial needs that characterize modern society. This second sense of freedom, the freedom from need, makes up a particularly insightful and revolutionary component of Rousseau’s philosophy. Rousseau believed modern man’s enslavement to his own needs was responsible for all sorts of societal ills, from exploitation and domination of others to poor self-esteem and depression. Rousseau believed that good government must have the freedom of all its citizens as its most fundamental objective. The Social Contract in particular is Rousseau’s attempt to imagine the form of government that best affirms the individual freedom of all its citizens, with certain constraints inherent to a complex, modern, civil society. Rousseau acknowledged that as long as property and laws exist, people can never be as entirely free in modern society as they are in the state of nature, a point later echoed by Marx and many other Communist and anarchist social philosophers. Nonetheless, Rousseau strongly believed in the existence of certain principles of government that, if enacted, can afford the members of society a level of freedom that at least approximates the freedom enjoyed in the state of nature. In The Social Contract and his other works of political philosophy, Rousseau is devoted to outlining these principles and how they may be given expression in a functional modern state. Defining the Natural and the State of Nature For Rousseau to succeed in determining which societal institutions and structures contradict man’s natural goodness and freedom, he must first define the ”natural”. Rousseau strips away all the ideas that centuries of development have imposed on the true nature of man and concludes that many of the ideas we take for granted, such as property, law, and moral inequality, actually have no basis in nature. For Rousseau, modern society generally compares unfavorably to the ”state of nature.” As Rousseau discusses in the Discourse on Inequality and The Social Contract, the state of nature is the hypothetical, prehistoric place and time where human beings live uncorrupted by society. The most important characteristic of the state of nature is that people have complete physical freedom and are at liberty to do essentially as they wish. That said, the state of nature also carries the drawback that human beings have not yet discovered rationality or morality. In different works, Rousseau alternately emphasizes the benefits and shortfalls of the state of nature, but by and large he reveres it for the physical freedom it grants people, allowing them to be unencumbered by the coercive influence of the state and society. In this regard, Rousseau’s conception of the state of nature is entirely more positive than Hobbes’s conception of the same idea, as Hobbes, who originated the term, viewed the state of nature as essentially a state of war and savagery. This difference in definition indicates the two philosophers’ differing views of human nature, which Rousseau viewed as essentially good and Hobbes as essentially base and brutal. Finally, Rousseau acknowledged that although we can never return to the state of nature, understanding it is essential for society’s members to more fully realize their natural goodness. The Danger of Need Rousseau includes an analysis of human need as one element in his comparison of modern society and the state of nature. According to Rousseau, “needs” result from the passions, which make people desire an object or activity. In the state of nature, human needs are strictly limited to those things that ensure survival and reproduction, including food, sleep, and sex. By contrast, as cooperation and division of labor develop in modern society, the needs of men multiply to include many nonessential things, such as friends, entertainment, and luxury goods. As time goes by and these sorts of needs increasingly become a part of everyday life, they become necessities. Although many of these needs are initially pleasurable and even good for human beings, men in modern society eventually become slaves to these superfluous needs, and the whole of society is bound together and shaped by their pursuit. As such, unnecessary needs are the foundation of modern “moral inequality,” in that the pursuit of needs inevitably means that some will be forced to work to fulfill the needs of others and some will dominate their fellows when in a position to do so. The Possibility of Authenticity in Modern Life Linked to Rousseau’s general attempt to understand how modern life differs from life in the state of nature is his particular focus on the question of how authentic the life of man is in modern society. By authentic, Rousseau essentially means how closely the life of modern man reflects the positive attributes of his natural self. Not surprisingly, Rousseau feels that people in modern society generally live quite inauthentic lives. In the state of nature, man is free to simply attend to his own natural needs and has few occasions to interact with other people. He can simply “be,” while modern man must often “appear” as much as “be” so as to deviously realize his ridiculous needs. The entire system of artificial needs that governs the life of civil society makes authenticity or truth in the dealings of people with one another almost impossible. Since individuals are always trying to deceive and/or dominate their fellow citizens to realize their own individual needs, they rarely act in an authentic way toward their fellow human beings. Even more damningly, the fact that modern people organize their lives around artificial needs means that they are inauthentic and untrue to themselves as well. To Rousseau’s mind, the origin of civil society itself can be traced to an act of deception, when one man invented the notion of private property by enclosing a piece of land and convincing his simple neighbors “this is mine,” while having no truthful basis whatsoever to do so. Given this fact, the modern society that has sprung forth from this act can be nothing but inauthentic to the core. The Unnaturalness of Inequality For Rousseau, the questions of why and how human beings are naturally equal and unequal, if they are unequal at all, are fundamental to his larger philosophical enquiry. To form his critique of modern society’s problems, he must show that many of the forms of inequality endemic to society are in fact not natural and can therefore be remedied. His conclusions and larger line of reasoning in this argument are laid out in the Discourse on Inequality, but the basic thrust of his argument is that human inequality as we know it does not exist in the state of nature. In fact, the only kind of natural inequality, according to Rousseau, is the physical inequality that exists among men in the state of nature who may be more or less able to provide for themselves according to their physical attributes. Accordingly, all the inequalities we recognize in modern society are characterized by the existence of different classes or the domination and exploitation of some people by others. Rousseau terms these kinds of inequalities moral inequalities, and he devotes much of his political philosophy to identifying the ways in which a just government can seek to overturn them. In general, Rousseau’s meditations on inequality, as well as his radical assertion of the notion that all men are by-and-large equal in their natural state, were important inspirations for both the American and French Revolutions. The General Will and the Common Good Perhaps the most difficult and quasi-metaphysical concept in Rousseau’s political philosophy is the principle of the general will. As Rousseau explains, the general will is the will of the sovereign, or all the people together, that aims at the common good—what is best for the state as a whole. Although each individual may have his or her own particular will that expresses what is good for him or her, in a healthy state, where people correctly value the collective good of all over their own personal good, the amalgamation of all particular wills, the “will of all,” is equivalent to the general will. In a state where the vulgarities of private interest prevail over the common interests of the collective, the will of all can be something quite different from the general will. The most concrete manifestation of the general will in a healthy state comes in the form of law. To Rousseau, laws should always record what the people collectively desire (the general will) and should always be universally applicable to all members of the state. Further, they should exist to ensure that people’s individual freedom is upheld, thereby guaranteeing that people remain loyal to the sovereign at all times. Discourse on Inequality Rousseau’s project in the Discourse on Inequality is to describe all the sorts of inequality that exist among human beings and to determine which sorts of inequality are “natural” and which “unnatural” (and therefore preventable). Rousseau begins by discussing man in his state of nature. For Rousseau, man in his state of nature is essentially an animal like any other, driven by two key motivating principles: pity and self-preservation. In the state of nature, which is more a hypothetical idea than an actual historical epoch, man exists without reason or the concept of good and evil, has few needs, and is essentially happy. The only thing that separates him from the beasts is some sense of unrealized perfectability. This notion of perfectability is what allows human beings to change with time, and according to Rousseau it becomes important the moment an isolated human being is forced to adapt to his environment and allows himself to be shaped by it. When natural disasters force people to move from one place to another, make contact with other people, and form small groups or elementary societies, new needs are created, and men begin to move out of the state of nature toward something very different. Rousseau writes that as individuals have more contact with one another and small groupings begin to form, the human mind develops language, which in turn contributes to the development of reason. Life in the collective state also precipitates the development of a new, negative motivating principle for human actions. Rousseau calls this principle amour propre, and it drives men to compare themselves to others. This drive toward comparison to others is not rooted only in the desire to preserve the self and pity others. Rather, comparison drives men to seek domination over their fellow human beings as a way of augmenting their own happiness. Rousseau states that with the development of amour propre and more complex human societies, private property is invented, and the labor necessary for human survival is divided among different individuals to provide for the whole. This division of labor and the beginning of private property allow the property owners and nonlaborers to dominate and exploit the poor. Rousseau observes that this state of affairs is resented by the poor, who will naturally seek war against the rich to end their unfair domination. In Rousseau’s history, when the rich recognize this fact, they deceive the poor into joining a political society that purports to grant them the equality they seek. Instead of granting equality, however, it sanctifies their oppression and makes an unnatural moral inequality a permanent feature of civil society. Rousseau’s argument in the Discourse is that the only natural inequality among men is the inequality that results from differences in physical strength, for this is the only sort of inequality that exists in the state of nature. As Rousseau explains, however, in modern societies the creation of laws and property have corrupted natural men and created new forms of inequality that are not in accordance with natural law. Rousseau calls these unjustifiable, unacceptable forms of inequality moral inequality, and he concludes by making clear that this sort of inequality must be contested. Although Rousseau would later develop many of the Discourse main points more expansively, it is significant as the first work to contain all the central elements of his philosophy. In the moral and political realm, the fundamental concept here is moral inequality, or unnatural forms of inequality that are created by human beings. Rousseau is clear that all such forms of inequality are morally wrong and as such must be done away with. The means by which moral inequality is to be banished is not a topic Rousseau broaches here, though this is a question that was hotly debated during the French Revolution and subsequent revolutions in the centuries since. In the Discourse on Inequality, Rousseau uses Hobbes’s concept of the state of nature but describes it in a very different way. Whereas Hobbes described the state of nature as a state of constant war populated by violent, self-interested brutes, Rousseau holds that the state of nature is generally a peaceful, happy place made up of free, independent men. To Rousseau, the sort of war Hobbes describes is not reached until man leaves the state of nature and enters civil society, when property and law create a conflict between rich and poor. Aside from foreshadowing the work of Marx and later theorists of class relations and societal inequality, Rousseau’s conception of natural man is a key principle in all his work: man is naturally good and is corrupted only by his own delusions of perfectability and the harmful elements of his capacity for reason. The means by which human beings are corrupted and the circumstances under which man agrees to leave the state of nature and enter human civil society are the focal points of Rousseau’s masterpiece, The Social Contract. The Social Contract Rousseau begins The Social Contract with the most famous words he ever wrote: “Men are born free, yet everywhere are in chains.” From this provocative opening, Rousseau goes on to describe the myriad ways in which the “chains” of civil society suppress the natural birthright of man to physical freedom. He states that the civil society does nothing to enforce the equality and individual liberty that were promised to man when he entered into that society. For Rousseau, the only legitimate political authority is the authority consented to by all the people, who have agreed to such government by entering into a social contract for the sake of their mutual preservation. Rousseau describes the ideal form of this social contract and also explains its philosophical underpinnings. To Rousseau, the collective grouping of all people who by their consent enter into a civil society is called the sovereign, and this sovereign may be thought of, metaphorically at least, as an individual person with a unified will. This principle is important, for while actual individuals may naturally hold different opinions and wants according to their individual circumstances, the sovereign as a whole expresses the general will of all the people. Rousseau defines this general will as the collective need of all to provide for the common good of all. For Rousseau, the most important function of the general will is to inform the creation of the laws of the state. These laws, though codified by an impartial, noncitizen “lawgiver,” must in their essence express the general will. Accordingly, though all laws must uphold the rights of equality among citizens and individual freedom, Rousseau states that their particulars can be made according to local circumstances. Although laws owe their existence to the general will of the sovereign, or the collective of all people, some form of government is necessary to carry out the executive function of enforcing laws and overseeing the day-to-day functioning of the state. Rousseau writes that this government may take different forms, including monarchy, aristocracy, and democracy, according to the size and characteristics of the state, and that all these forms carry different virtues and drawbacks. He claims that monarchy is always the strongest, is particularly suitable to hot climates, and may be necessary in all states in times of crisis. He claims that aristocracy, or rule by the few, is most stable, however, and in most states is the preferable form. Rousseau acknowledges that the sovereign and the government will often have a frictional relationship, as the government is sometimes liable to go against the general will of the people. Rousseau states that to maintain awareness of the general will, the sovereign must convene in regular, periodic assemblies to determine the general will, at which point it is imperative that individual citizens vote not according to their own personal interests but according to their conception of the general will of all the people at that moment. As such, in a healthy state, virtually all assembly votes should approach unanimity, as the people will all recognize their common interests. Furthermore, Rousseau explains, it is crucial that all the people exercise their sovereignty by attending such assemblies, for whenever people stop doing so, or elect representatives to do so in their place, their sovereignty is lost. Foreseeing that the conflict between the sovereign and the government may at times be contentious, Rousseau also advocates for the existence of a tribunate, or court, to mediate in all conflicts between the sovereign and the government or in conflicts between individual people. Rousseau’s central argument in The Social Contract is that government attains its right to exist and to govern by “the consent of the governed.” Today this may not seem too extreme an idea, but it was a radical position when The Social Contract was published. Rousseau discusses numerous forms of government that may not look very democratic to modern eyes, but his focus was always on figuring out how to ensure that the general will of all the people could be expressed as truly as possible in their government. He always aimed to figure out how to make society as democratic as possible. At one point in The Social Contract, Rousseau admiringly cites the example of the Roman republic’s comitia to prove that even large states composed of many people can hold assemblies of all their citizens. Just as he did in his Discourse on Inequality, Rousseau borrows ideas from the most influential political philosophers of his day, though he often comes to very different conclusions. For example, though his conception of society as being akin to an individual person resonates with Hobbes’s conception of the Leviathan Rousseau’s labeling of this metaphorical individual as the sovereign departs strongly from Hobbes, whose own idea of the sovereign was of the central power that held dominion over all the people. Rousseau, of course, believed the sovereign to be the people and to always express their will. In his discussion of the tribunate, or the court that mediates in disputes between governmental branches or among people, Rousseau echoes ideas about government earlier expressed by Locke. Both Locke’s and Rousseau’s discussions of these institutions influenced the system of checks and balances enshrined in the founding documents of the United States. The Social Contract is one of the single most important declarations of the natural rights of man in the history of Western political philosophy. It introduced in new and powerful ways the notion of the “consent of the governed” and the inalienable sovereignty of the people, as opposed to the sovereignty of the state or its ruler(s). It has been acknowledged repeatedly as a foundational text in the development of the modern principles of human rights that underlie contemporary conceptions of democracy. SparkNotes Editors. “SparkNote on Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778).” SparkNotes.com. SparkNotes LLC. 2005. Web. 2 Oct. 2012. Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679) The Materialist View of Human Nature Hobbes believed that all phenomena in the universe, without exception, can be explained in terms of the motions and interactions of material bodies. He did not believe in the soul, or in the mind as separate from the body, or in any of the other incorporeal and metaphysical entities in which other writers have believed. Instead, he saw human beings as essentially machines, with even their thoughts and emotions operating according to physical laws and chains of cause and effect, action and reaction. As machines, human beings pursue their own self-interest relentlessly, mechanically avoiding pain and pursuing pleasure. Hobbes saw the commonwealth, or society, as a similar machine, larger than the human body and artificial but nevertheless operating according to the laws governing motion and collision. In putting together this materialist view of the world, Hobbes was influenced by his contemporaries Galileo and Kepler, who had discovered laws governing planetary motion, thereby discrediting much of the Aristotelian worldview. Hobbes hoped to establish similar laws of motion to explain the behavior of human beings, but he was more impressed by Galileo and Kepler’s mathematical precision than by their use of empirical data and observation. Hobbes hoped to arrive at his laws of motion deductively, in the manner of geometrical proofs. It is important to note that Hobbes was not in any position to prove that all of human experience can be explained in terms of physical and mechanical processes. That task would have required scientific knowledge far beyond that possessed by the seventeenth century. Even today, science is nowhere near being able to fully explain human experience in physical terms, even though most people tend to believe that science will one day be able to do just that. In the absence of such a detailed explanation, the image of the human being as a machine in Hobbes’s writing remains more of a metaphor than a philosophical proof. The Inadequacy of Observation as a Foundation of Knowledge Hobbes rejected what we now know as the scientific method because he believed that the observation of nature itself is too subjective a basis on which to ground philosophy and science. Hobbes contested the scientific systems of the natural philosophers Francis Bacon and Robert Boyle. These major figures in the Scientific Revolution in England base their natural philosophy on a process of inductive reasoning, making inferences and conclusions based on the observation of nature and the manipulation of nature through experimentation. For Hobbes, the chief aim of philosophy is to create a totalizing system of truth that bases all its claims on a set of foundational principles and is universally demonstrable through the logic of language. He rejects the observation of nature as a means of ascertaining truth because individual humans are capable of seeing the world in vastly different ways. He rejects inductive reasoning, arguing that the results of contrived experiments carried out by a few scientists can never be universally demonstrable outside of the laboratory. Accordingly, Hobbes holds that geometry is the branch of knowledge that best approximates the reasoning that should form the basis of a true philosophy. He calls for a philosophy based on universally agreed-upon first principles that form the foundation for subsequent assertions. Fear as the Determining Factor in Human Life Hobbes maintained that the constant back-and-forth mediation between the emotion of fear and the emotion of hope is the defining principle of all human actions. Either fear or hope is present at all times in all people. In a famous passage of Leviathan, Hobbes states that the worst aspect of the state of nature is the “continual fear and danger of violent death.” In the state of nature, as Hobbes depicts it, humans intuitively desire to obtain as much power and “good” as they can, and there are no laws preventing them from harming or killing others to attain what they desire. Thus, the state of nature is a state of constant war, wherein humans live in perpetual fear of one another. This fear, in combination with their faculties of reason, impels men to follow the fundamental law of nature and seek peace among each other. Peace is attained only by coming together to forge a social contract, whereby men consent to being ruled in a commonwealth governed by one supreme authority. Fear creates the chaos endemic to the state of nature, and fear upholds the peaceful order of the civil commonwealth. The contract that creates the commonwealth is forged because of people’s fear, and it is enforced by fear. Because the sovereign at the commonwealth’s head holds the power to bodily punish anyone who breaks the contract, the natural fear of such harm compels subjects to uphold the contract and submit to the sovereign’s will. Good and Evil as Appetite and Aversion Hobbes believed that in man’s natural state, moral ideas do not exist. Thus, in speaking of human nature, he defines good simply as that which people desire and evil as that which they avoid, at least in the state of nature. Hobbes uses these definitions as bases for explaining a variety of emotions and behaviors. For example, hope is the prospect of attaining some apparent good, whereas fear is the recognition that some apparent good may not be attainable. Hobbes admits, however, that this definition is only tenable as long as we consider men outside of the constraints of law and society. In the state of nature, when the only sense of good and evil derives from individuals’ appetites and desires, general rules about whether actions are good or evil do not exist. Hobbes believes that moral judgments about good and evil cannot exist until they are decreed by a society’s central authority. This position leads directly to Hobbes’s belief in an autocratic and absolutist form of government. Absolute Monarchy as the Best Form of Government Hobbes promoted that monarchy is the best form of government and the only one that can guarantee peace. In some of his early works, he only says that there must be a supreme sovereign power of some kind in society, without stating definitively which sort of sovereign power is best. In Leviathan, however, Hobbes unequivocally argues that absolutist monarchy is the only right form of government. In general, Hobbes seeks to define the rational bases upon which a civil society could be constructed that would not be subject to destruction from within. Accordingly, he delineates how best to minimize discord, disagreement, and factionalism within society—whether between state and church, between rival governments, or between different contending philosophies. Hobbes believes that any such conflict leads to civil war. He holds that any form of ordered government is preferable to civil war. Thus he advocates that all members of society submit to one absolute, central authority for the sake of maintaining the common peace. In Hobbes’s system, obedience to the sovereign is directly tied to peace in all realms. The sovereign is empowered to run the government, to determine all laws, to be in charge of the church, to determine first principles, and to adjudicate in philosophical disputes. For Hobbes, this is the only sure means of maintaining a civil, peaceful polity and preventing the dissolution of society into civil war. SparkNotes Editors. “SparkNote on Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679).” SparkNotes.com. SparkNotes LLC. 2005. Web. 3 Oct. 2012. John Locke Locke's Second Treatise on Civil Government The Second Treatise of Government places sovereignty into the hands of the people. Locke's fundamental argument is that people are equal and invested with natural rights in a state of nature in which they live free from outside rule. In the state of nature, natural law governs behavior, and each person has license to execute that law against someone who wrongs them by infringing on their rights. People take what they need from the earth, but hoard just enough to cover their needs. Eventually, people begin to trade their excess goods with each other, until they develop a common currency for barter, or money. Money eliminates limits on the amount of property they can obtain (unlike food, money does not spoil), and they begin to gather estates around themselves and their families. People then exchange some of their natural rights to enter into society with other people, and be protected by common laws and a common executive power to enforce the laws. People need executive power to protect their property and defend their liberty. The civil state is beholden to the people, and has power over the people only insofar as it exists to protect and preserve their welfare. Locke describes a state with a separate judicial, legislative, and executive branch--the legislative branch being the most important of the three, since it determines the laws that govern civil society. People have the right to dissolve their government, if that government ceases to work solely in their best interest. The government has no sovereignty of its own--it exists to serve the people. To sum up, Locke's model consists of a civil state, built upon the natural rights common to a people who need and welcome an executive power to protect their property and liberties; the government exists for the people's benefit and can be replaced or overthrown if it ceases to function toward that primary end. Overall Analysis The Second Treatise of Government remains a cornerstone of Western political philosophy. Locke's theory of government based on the sovereignty of the people has been extraordinarily influential since its publication in 1690--the concept of the modern liberal-democratic state is rooted in Locke's writings. Locke's Second Treatise starts with a liberal premise of a community of free, equal individuals, all possessed of natural rights. Since these individuals will want to acquire goods and will come into inevitable conflict, Locke invokes a natural law of morality to govern them before they enter into society. Locke presumes people will understand that, in order to best protect themselves and their property, they must come together into some sort of body politic and agree to adhere to certain standards of behavior. Thus, they relinquish some of their natural rights to enter into a social compact. In this civil society, the people submit natural freedoms to the common laws of the society; in return, they receive the protection of the government. By coming together, the people create an executive power to enforce the laws and punish offenders. The people entrust these laws and the executive power with authority. When, either through an abuse of power or an impermissible change, these governing bodies cease to represent the people and instead represent either themselves or some foreign power, the people may--and indeed should-rebel against their government and replace it with one that will remember its trust. This is perhaps the most pressing concern of Locke's Second Treatise, given his motivation in writing the work (justifying opposition to Charles II) and publishing it (justifying the revolution of King William)--to explain the conditions in which a people has the right to replace one government with another. Locke links his abstract ideals to a deductive theory of unlimited personal property wholly protected from governmental invention; in fact, in some cases Locke places the sanctity of property over the sanctity of life (since one can relinquish one's life by engaging in war, but cannot relinquish one's property, to which others might have ownership rights). This joining of ideas--consensual, limited government based upon natural human rights and dignity, and unlimited personal property, based on those same rights, makes the Second Treatise a perfectly-constructed argument against absolutism and unjust governments. It appeals both to abstract moral notions and to a more grounded view of the self-interest that leads people to form societies and governments. SparkNotes Editors. “SparkNote on Locke's Second Treatise on Civil Government.” SparkNotes.com. SparkNotes LLC. n.d.. Web. 2 Oct. 2012. Baron de Montesquieu (1689-1755) One of the leading political thinkers of the French Enlightenment, the Baron de Montesquieu (1689–1755), drew great influence from the works of Locke. Montesquieu’s most critical work, The Spirit of Laws (1748), tackled and elaborated on many of the ideas that Locke had introduced. He stressed the importance of a separation of powers and was one of the first proponents of the idea of a system of checks and balances in government. The Spirit of the Laws Montesquieu's aim in The Spirit of the Laws is to explain human laws and social institutions. . . . Laws should be adapted "to the people for whom they are framed..., to the nature and principle of each government, ... to the Understanding why we have the laws we do is important in itself. However, it also serves practical purposes. Most importantly, it will discourage misguided attempts at reform. Montesquieu believes that to live under a stable, non-despotic government that leaves its law-abiding citizens more or less free to live their lives is a great good, and that no such government should be lightly tampered with. . . . Understanding our laws will also help us to see which aspects of them are genuinely in need of reform, and how these reforms might be accomplished. For instance, Montesquieu believes that the laws of many countries can be made be more liberal and more humane, and that they can often be applied less arbitrarily, with less scope for the unpredictable and oppressive use of state power. Likewise, religious persecution and slavery can be abolished, and commerce can be encouraged. These reforms would generally strengthen monarchical governments, since they enhance the freedom and dignity of citizens. If lawmakers understand the relations between laws on the one hand and conditions of their countries and the principles of their governments on the other, they will be in a better position to carry out such reforms without undermining the governments they seek to improve. Montesquieu on Democracy In a democracy, the people are sovereign. They may govern through ministers, or be advised by a senate, but they must have the power of choosing their ministers and senators for themselves. The principle of democracy is political virtue, by which Montesquieu means "the love of the laws and of our country" (SL 4.5), including its democratic constitution. The form of a democratic government makes the laws governing suffrage and voting fundamental. The need to protect its principle, however, imposes far more extensive requirements. The virtue required by a functioning democracy is not natural. It requires "a constant preference of public to private interest" (SL 4.5); it "limits ambition to the sole desire, to the sole happiness, of doing greater services to our country than the rest of our fellow citizens" (SL 5.3); and it "is a self-renunciation, which is ever arduous and painful" (SL 4.5). . . . A democracy must educate its citizens to identify their interests with the interests of their country, and should have censors. It should seek to establish frugality by law, so as to prevent its citizens from being tempted to advance their own private interests at the expense of the public good; for the same reason, the laws by which property is transferred should aim to preserve an equal distribution of property among citizens. Its territory should be small, so that it is easy for citizens to identify with it, and more difficult for extensive private interests to emerge. Democracies can be corrupted in two ways: by what Montesquieu calls "the spirit of inequality" and "the spirit of extreme equality" (SL 8.2). The spirit of inequality arises when citizens no longer identify their interests with the interests of their country, and therefore seek both to advance their own private interests at the expense of their fellow citizens, and to acquire political power over them. The spirit of extreme equality arises when the people are no longer content to be equal as citizens, but want to be equal in every respect. In a functioning democracy, the people choose magistrates to exercise executive power, and they respect and obey the magistrates they have chosen. If those magistrates forfeit their respect, they replace them. When the spirit of extreme equality takes root, however, the citizens neither respect nor obey any magistrate. They "want to manage everything themselves, to debate for the senate, to execute for the magistrate, and to decide for the judges" (SL 8.2). Eventually the government will cease to function, the last remnants of virtue will disappear, and democracy will be replaced by despotism. . . . Montesquieu on Liberty According to Montesquieu, political liberty is "a tranquility of mind arising from the opinion each person has of his safety" (SL 11.6). Liberty is not the freedom to do whatever we want: if we have the freedom to harm others, for instance, others will also have the freedom to harm us, and we will have no confidence in our own safety. Liberty involves living under laws that protect us from harm while leaving us free to do as much as possible, and that enable us to feel the greatest possible confidence that if we obey those laws, the power of the state will not be directed against us. If it is to provide its citizens with the greatest possible liberty, a government must have certain features. First, since "constant experience shows us that every man invested with power is apt to abuse it ... it is necessary from the very nature of things that power should be a check to power" (SL 11.4). This is achieved through the separation of the executive, legislative, and judicial powers of government. If different persons or bodies exercise these powers, then each can check the others if they try to abuse their powers. But if one person or body holds several or all of these powers, then nothing prevents that person or body from acting tyrannically; and the people will have no confidence in their own security. Certain arrangements make it easier for the three powers to check one another. Montesquieu argues that the legislative power alone should have the power to tax, since it can then deprive the executive of funding if the latter attempts to impose its will arbitrarily. Likewise, the executive power should have the right to veto acts of the legislature, and the legislature should be composed of two houses, each of which can prevent acts of the other from becoming law. The judiciary should be independent of both the legislature and the executive, and should restrict itself to applying the laws to particular cases in a fixed and consistent manner, so that "the judicial power, so terrible to mankind, … becomes, as it were, invisible", and people "fear the office, but not the magistrate" (SL 11.6). Liberty also requires that the laws concern only threats to public order and security, since such laws will protect us from harm while leaving us free to do as many other things as possible. They should not prohibit what they do not need to prohibit: "all punishment which is not derived from necessity is tyrannical. The laws should be constructed to make it as easy as possible for citizens to protect themselves from punishment by not committing crimes. They should not be vague, since if they were, we might never be sure whether or not some particular action was a crime. Finally, the laws should make it as easy as possible for an innocent person to prove his or her innocence. They should concern outward conduct, not (for instance) our thoughts and dreams, since while we can try to prove that we did not perform some action, we cannot prove that we never had some thought. http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/montesquieu/#4.1 Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy