* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download MODULE 1: APPROACHES TO CANADIAN ECONOMIC HISTORY

Economic planning wikipedia , lookup

Economic democracy wikipedia , lookup

Steady-state economy wikipedia , lookup

Economics of fascism wikipedia , lookup

Non-monetary economy wikipedia , lookup

Business cycle wikipedia , lookup

Ragnar Nurkse's balanced growth theory wikipedia , lookup

Economic growth wikipedia , lookup

Chinese economic reform wikipedia , lookup

Production for use wikipedia , lookup

Economic calculation problem wikipedia , lookup

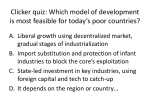

MODULE #1 APPROACHES TO CANADIAN ECONOMIC HISTORY - We will look at section 1.2 to examine the early staples economies in MODULE 2 - look at section 1.3 before studying MODULE 3 and section 1.4 to 1.9 before examining MODULE 5 1.1 Approaches to studying the relationship between economic theory, institutions and history. Text: Intro. pp IX-XII First Generation of Canadian Economic Historians (1888 to 1920). - used economic history as a means to comprehend the economic development of Canada as a new nation - prominent academics included: I. Adam Shortt at Queens (appointed in 1888) II. O.D. Skeleton – a younger colleague III. James Mayor at U. of T. (appointed in 1893) IV. Stephen Leacock at McGill (appointed in 1903) - a multi-volume series Canada and It’s Provinces was published in 1914 Second Generation of Canadian Economic Historians (1920 – 1963). - identified with the staples thesis - staples are commodities that have a high natural resource content produced for export and they completely dominate other activities - school of economic thought was established by: I. Harold Innis (U. of T.) 1 - influenced first text books II. W.A. Mackintosh* (Queens) III. Easterbrook and Aitken (Textbook 1956) * Inspired by G. Callender and the frontier thesis Third Generation of Canadian Economic Historians (1963 – Present) - often referred to as the ‘new’ (or neoclassical) economic history - they believe that the principal theme or ‘story’ of Canadian economic development must be guided by economic theory - textbooks include: I. Marr and Patterson (1980) II. Pomfret (1981) III. Our textbook - we will examine this approach in more detail after we look at MODULE 2. 2 1.2 Innis Staple Thesis of Pervasive and Persistent Influences Classic Studies I. The Fur Trade in Canada II. The Cod Fisheries: The History of an International Economy General Features - focuses on the creation of distinctive social, economic and political institutions that take root in natural resources ‘abundant’ regions of European ‘settlement’. - Innis stressed that the ‘character’ of each staple created a ‘bias’ in the pattern of growth and development and the establishment of ‘distinct societies’. Assumption in Classic Studies - Innis appears to assume certain conditions were prevalent in early staples economies and were persistent for a very long period of time Abundant natural resources endowments Shortage of local labour Static technology Small ‘domestic’ markets versus large international markets centred in ‘metropolitan’ Europe - Innis observed that technological change was relatively insignificant so growth was dependent on demand - The sparse population in the ‘hinterland’ provided little opportunity for the growth of local markets for input and output markets - Innis was strongly influenced by the ‘old’ institutional school of thought in the U.S. - Habits and rules are essential to understand human action and both are essential in the analysis of new institutions in staple producing economies 3 Importance of Spread Effects I. II. Transportation and Communication Location – specific activities (non-tradables) Interpretation of the Staples Thesis by the Authors of our Textbook (Introduction in earlier edition) Strength of the Staples Thesis 1) Consistent framework applied to different historical phenomena over very long periods of time (ie the longue duree of the Annales School).* 2) Comprehensive approach that draws on all areas of the social sciences * Amerindian societies on the Canadian Shield, fisheries off Newfoundland Limitations of the Staples Thesis 1) Rarely uses data and never uses a well defined or rigorous theory to test empirically 2) Decreasing relevance as the natural resource sector declines in relative size of economy 3) Important sectors are ignored and even whole regions are ignored or disappear from history 4) Breadth of analysis results in situations where I. Relationships between cause and effect are not clearly established II. Correlation is often used to imply causation III. Qualitative conclusions are made when quantitative ones would be more insightful 5) Focus on staple export sector overlooks the internal, domestic economy 4 1.3 MacKintosh Staples Theory of Emerging Internal Dynamics - influenced by American economic historians G.S. Callender and Gras - pioneered the staples approach with his 1923 article ‘Economic Factors in Canadian History’. - most enduring work was his ‘Economic Background to Dominion – Provincial Relations’ – part of a Royal Commission reporting in 1940 - also made a contribution to historical geography with his ‘Prairie Settlement: The Geographical Setting’ (1934). 5 1.4 Neoclassical Interpretation of the Staples Approach For Regions of European Settlement I) Staples theory of progressive development II) Neoclassical theory of export-led growth in newly settled regions 1.41 Watkins Staple Theory of Progressive Development - seminal article in the CJEPS (1963) makes an attempt to interpret the original ‘paradigm’ into a neoclassical framework - draws on earlier studies by R. Baldwin and D.C. North - makes a distinction between economic growth and development - also stresses the existence of the unique ‘character’ of the aggregate production function in early staple economies Definition of a Staple - those products (which are a bundle of goods and services) that have a ‘high’ natural resources content and large demand in external markets - they do not require any elaborate processing at the initial stages of production in the staple producing region - the value added content for primary manufacturing is relatively low - labour skills are often indigenous to the staple producing region - external prices in metropolitan markets must be high enough to bear transportation charges to international markets - factor proportions have a high natural resource (R) to labour-capital ratio Unique Factors That Establish New Staples 1) Discovery – Purposeful or accidental 6 2) Demand – strong demand in the metropolitan areas to induce producers to shift productive resources to the hinterland or to new areas of settlement 3) Technology – state of current technology must have the capacity to adapt to new economic environment and be innovative 4) Socio-Cultural Setting – entrepreneurs willing to undertake unknown risks and operate in an environment of greater uncertainty Growth in Early Staples Economies - staple exports are the leading sector and set the pace for extensive growth that is not accompanied by any technological or structural changes Modern Growth and Progressive Development - sustained increases in per capita output occur because of technical change, spillover effects and improvements in social and business organizations - technical change is driven by advances in science and technology - a transformation of social and business relationships stimulates entrepreneurship, innovation and productivity advances - spillover effects from a dynamic staple sector lead to: I. a process of diversification around the export base II. agglomeration economies that lower input costs via external economies Direct Impact of the Staples Sector - measured with the sectors own production function and transfer function which emerge within the context of historically specific institutional forms Resource Specific Production Function of the Staples sector Q = f (A, K, L, I, R) 7 Q = f (A, E, R) Q = (gross) output at producer prices of staples A = technology or productivity index E = Effort (bundle of K,L,I) R = Land inputs for Resource Sector only Staples Transfer Function in the Sphere of Physical Distribution and Exchange - the production function defines the creation of form utility for resource intensive commodities - the staples sector is the sphere of production while this defines the Sphere of Physical Distribution - transportation and storage - communications - utilities (no electrical generation) Sphere of Exchange - wholesale trade - retail trade - commercial banking (circulating capital) Character of Staples Aggregate Production and Transfer Functions - define the overall direct impact of staples activities which include: 1. Techniques of production, physical distribution and exchange which determine the factor proportion of inputs 2. Demand for factor inputs that add value in the staples sector a. Land – natural resources (or natural capital) b. Labour – workforce 8 c. (Real) Capital – investment in the replacement of older reproducible and additional new (net) investment d. Entrepreneurship 3. Distribution of income between factors employed directly in the staples sector 4. Demand for intermediate inputs 5. Possibilities for further processing Indirect Impact of the Staples Sector - the spread effects of staple activities are best illustrated using the concept of staple activities are best illustrated using the concept of demand – and supply – oriented inducements for growth outside the staples sector I. Demand Induced Expansion in Non-Staple Activities - growth of new sectors that are related to the success of the leading export sectors and result in diversification - best illustrated with the concept of linkages A. Backward Linkage Activities - sectors producing intermediate inputs of goods and services used by the staples sector - gross (i.e. replacement and net) investment of domestically produced capital goods - the transfer function of these sectors B. Forward Linkage Activities - those industries use staples as an intermediate input in ‘downstream’ activities 9 - they are induced, processing activities that add value to the staple and are partly dependent on technological considerations C. Final Demand Linkages - domestically produced consumer goods and services that are purchased by the owners of factor inputs in the staple sector - it is influenced by: absolute size of the workforce residence of the owners of capital and land distribution of income D. Fiscal Linkages - expenditures on physical and social infrastructure roads, schools, hospitals justice system - depends on public revenues from resource rents and the and the direct and indirect taxes flowing from the staples sector E. Lateral Linkages - non-staple activities that are not location-specific but grow because of the ‘prosperity’ generated by staples sector or the infrastructure of the transfer functions - ‘footloose’ activities that develop because of the indivisible nature of infrastructure for staples sector II. Supply Side Inducements in Non-Staple Activities A. Entrepreneurship 10 - depends on the opportunity of the staples sector and its ability to promote enterprise throughout the economy via: The development of new organizational designs and structures Foster the creation of new products and market opportunities The introduction of appropriate new technologies B. Workforce - the size and quality of the workforce is influenced by Demographic transitions o Fertility rate o Mortality rate Education and training Immigration C. Public policy Growth Path of a Staples Economy I. Factor Input Markets and Favourable Factor Properties - the pre-existence of an abundance of natural resources lays the foundations for a regions comparative advantage in both the domestic and international economy - expansion is initially the demand-led growth for staple exports followed by spread effects via linkages - the resulting increase in demand for factor-inputs leads to ‘surplus’ income in the form of high labour income economic profits from real capital economic rents from natural resources 11 II. Capacity to Transform - Watkins draws on Kindleberger - Sustained growth requires an ability to shift resources as markets evolve - Requires an absence of inhibiting traditions that foster an ‘export mentality’ and eventually a ‘staple trap’ - Institutions and values must be formed anew based on the distinct conditions of newly settled regions Simple Model of Staples Economy Sectors include: Resources (original staples sector) Transformation Transportation, Communication and Trade – sphere of physical distribution and exchange Other Private Sector Services Public Sector Services Tableau of Product Flows 4B See the TABLEAU OF PRODUCT OUTPUT AND FACTOR INPUT FLOWS APPENDIX TO MODULE 1.42 Simple Ricardian “Corn” Model (1) Stage of Economic Development 12 - mature, agrarian economy - primitive accumulation - state of autarky - no technological change - ong-run equilibrium (2) Institutional Setting - there are three (3) distinct classes that contribute “factors of production”: (I) Free labour -provide work effort and receive subsistence income (II) Capitalists - provide working capital* inputs at the beginning of each season - a “dose” of inputs is made up of 20 tonnes of wheat and 20 sheep (III) Landlords - exclusive owners of land that has various fertility on their estates * Equivalent to free or circulating capital that depreciates after one year and/or intermediate inputs (3) Technology - fixed factors and diminishing returns - a “dose” of labour and working capital is applied to 10 hectares until land rents fall to zero See graphs Agriculture & Household Mfg. Consumption Investment Labour Capitalist Landlord Agriculture & Household Mfg Wages 500 Gross Profit 300 Rent 200 Value Added 1,000 (GDP) 500 100* Total Output (Corn Seed) 200 200 *Net Profit 13 1,000 Real Factor Inputs Labour: 10 person-years Working Capital: 20 units * 10 = 200 where 20 units = 20 c\nt corn seed 20 sheep Land: 1,000 hectares Simple Ricardian “Corn” Model with Technological Change -upward shift in TP, MP and AP curves now creates a new “surplus” over traditional subsistence and creates an opportunity to I) develop an industrial and service sector II) trade with other economies that are willing to export industrial products in exchange for agricultural products See graphs and charts 1.42 McCallum Staple Theory of Progressive Development - works within the Watkins framework but adds a perspective from economic geography and the new institutional economics - staple activities that exploit new endowments of natural resources create both linkage and wealth benefits 14 - the groups and owners of factor inputs who capture linkage effects depend on a complex interaction between the rules and laws that govern trade, government policies and institutions - study compares the contrasting patterns of growth and development stemming from the wheat economy in Ontario and the Prairies - linkage appropriation and wealth benefits derived from staple activities will flow to those regions that have a higher endowment of accumulation of population productive capacity financial capacity entrepreneurial class technology and know-how political power 1.5 Critics of the Staples Approach - does not place enough emphasis on domestic supply side factors that help explain the growth and development of economics such as Ontario - Buckley believed that the staples approach was no longer relevant past the 1820’s due to the growing complexity of the emerging industrial and urban economy 15 - Institutionalists such as Easterbrook would see this approach as too analytical and does not place enough emphasis on distinctive socio-cultural developments and the role of state enterprise - Business historians would view the role at entrepreneurship as superficial to the analysis instead of the key factor in the Schumpeter tradition - Neoclassical growth theorists would have the same view with regard to the role of technological change as highlighted by Chambers and Gordon - The authors of the 3rd edition of our textbook contend that the effects of exportled growth are temporary and geographically limited as ‘Canada’s growth has been episodic and regional in nature’ (pp XVIII) - A single minded staples approach is inappropriate to defining Canada’s overall growth and development - This view is highlighted in their interpretation of the political evolution of the country and the formation of public policy initiatives 1.7 Neo-Classical Growth - the growth accounting frame-work developed by Solow is illustrated by an aggregate production function and exogenous technological change Q = f (A, K, L, R, T) Q = GDP at factor cost A = technology or productivity index (not ‘T’ as before) 16 K = (reproducible) capital inputs L = workforce R = natural resource inputs or land t = 1, 2, 3, ……in periods of time Note: the model is for a closed economy and does not include intermediate inputs (I) - the Cobb Douglas form is Qt = At Kta Ltb Rtc Where a = capitals share at GDP (=MPK) b = labour share at GDP (=MPL) c = lands share at GDP (= MPR) - the growth accounting equation is derived as follows 1.8 Institutional School of Economics “Old” Institutionalism - offers a radically different perspective on the nature of human agency based on the concept of habit - habits and rules are seen as essential for human action; and both are crucial for the analysis of institutions. 17 Basis of Microeconomic Price Theory (I) Neoclassical – emphasis on rational economic man. - relies on the universal concepts of supply, demand and marginal utility (II) Institutionalists - prices are social conventions that are reinforced by habits and embedded in specific institutions - such conventions are varied and reflect the different types of commodity institution, mode of calculation and pricing process - have no general theory of price but a set of guidelines approaches to specific problem that lead to historically and institutionally specific studies Macroeconomic Analysis (I) Contemporary – focus on equilibrium conditions of interdependent markets (II) Institutionalists – examine the structure of the macroeconomic system see below - focus on the patterns and regularities of human behaviour that contains a great deal of imitation; inertia and cumulative causation Other Features of “Old” Institutionalism Hodgson page 173-74 (1) stress the real causal linkages involved rather than more correlation between variables. General Features of an Institution & Organizations - based on the way of thought or action of some prevalence and permanence which is imbedded in the habits of a group or the reactions of a people 18 - refers to the complex of socially learned and shared values, norms, beliefs, meanings, symbols, customs and standards that delineate the rate of expected and accepted behaviours in a particular context. - institutional structure and behavioural habit are mutually intertwined and mutually reinforcing. - an organization may be defined as a special subset of institutions, involving deliberate coordination and recognized principles of sovereignty and control Common Characteristics of Institutions and Organizations Hodgson page 179-80 Critique of other Institutional Approaches 1) Cultural Determinists (?) -place too much emphasis on the molding of individuals by institutions. 2) Neoclassical Institutionalism -see Williamson figure on page 597 -seeks to explain the emergence of institution by reference to a model of rational individual behaviour, tracing out the unintended consequences in terms o human interactions - it assumes an initial institution free state of nature and the explanatory movement is from individuals to institutions, taking individuals as given Hodgson Figure 1, page 176 Douglas North has proposed that institutions are “the rules of the game” that determine how and why markets and individuals behave as they do - what is required is a theory of process, evolution and learning rather than a theory that proceeds from an original, institution free “state of nature” 19 - a detailed analysis of the evolution of specific habits and rules – including the pecuniary rationality of “economic man” in a market economy – should be installed at the core of economics and social theory - at its foundation; institutional economics has grater generality and encompasses neoclassical economics as a special case. First, there is a degree of emphasis on institutional and cultural factors that is not found in mainstream economic theory. Second, the analysis is openly inter-disciplinary, in recognizing insights from politics, sociology, psychology, and other sciences. Third, there is no recourse to the model of the rational, utility-maximizing agent. Inasmuch as a conception of the individual agent is involved, it is one which emphasizes both the prevalence of habit and the possibility of capricious novelty. Fourth, mathematical and statistical techniques are recognized as the servants of, rather than the essence of, economic theory. Fifth, the analysis does not start by building mathematical models: it starts from stylized facts and theoretical conjectures concerning causal mechanisms. Sixth, extensive use is made of historical and comparative empirical material concerning socio-economic institutions. In several of these respects, institutional economics is at variance with much of modern mainstream economic theory. Common characteristics: All institutions involve the interaction of agents, with crucial information feedbacks. All institutions have a number of characteristic and common conceptions and routines Institutions sustain, and are sustained by, shared conceptions and expectations. Although they are neither immutable nor immortal, institutions have relatively durable, self-reinforcing, and persistent qualities Institutions incorporate values, and processes of normative evaluation. In particular, institutions reinforce their own moral legitimation: that which endures is often-rightly or wrongly-seen as morally just. New Institutional Economics 20 - neoclassical growth theory has not succeeded as a complete explanation for growth processes - it predicts that if products and inputs are mobile between countries then per capita GDP should converge - explanations for dramatic and persistent differences in per capita GDP across countries are: 1) LDC’s have fewer key economic resources - especially modern technology 2) Political boundaries define the spatial borders of public policies and institutions of nation states - initial ‘endowments must include the institutional structures that societies inherit or adopt - the capacity of institutions to improve and adapt are also important Canada’s Rank in Real GDP Per Person 1870 1913 1950 1973 12 5 6 3 Source: Textbook (3rd edition) ppXXVI Approaches to Micro Price Theory I. Neoclassical - emphasis on rational decision making that takes utility functions as given - relies on universal concepts of supply, demand and marginal utility II. New Institutionalists - prices represent social conventions that are rein forced by habits and embodied in specific institutions 21 - such conventions are varied and reflect the different types of institutions, commodities, modes of calculations and pricing processes Approaches to Macro Analysis I. Contemporary - focus on equilibrium of interdependent markets II. New Institutionalists - examine the structure of an economic system and stress the real caused linkages rather than the correlation between variables - focus on the system of socially learned and shared values, norms. beliefs, meaning, symbols, customs and standards that define the range of expected and accepted behavior in a particular context - an organization may be defined as a special subset of institutions (i.e. Chandler approach in business history) 1.8 Synthesis of Approaches 22 Staples Approach of Second Generation of Economic Historians - narratives of how the stages of colonial development depended on a succession of staples whose characteristics set the pattern for the economic, social, culture and political evolution of newly settled regions Neoclassical Economic History (1960’s to Present) - called the ‘new’ economic history in the 1960’s and 1970’s - it stresses model building, quantification and hypothesis testing - the role of simplification and abstraction is required to examine economic events and activities - concepts such as the production possibility frontier require an understanding of opportunity cost, economic efficiency and potential comparative advantage - the new empirical emphasis permits one to draw powerful inferences from very little data using economic theory - general equilibrium models permit one to go beyond simple assertion and define a complete set of behavioral and technological relationships - traditional and new endogenous growth models stress the role of technological change in accounting for increases in per capita income - permit us to identify long-term shifts in the structure and performance of the economy and the ‘real’ forces that influence this transformation over time Strengths of Neoclassical Economic History 1) Rigorous 2) Models described economic relationships precisely 3) Causality is explicit 4) Quantitative analysis provides an accurate measure of absolute and relative importance 23 5) Counterfactual tests permit one to measure true economic costs and benefits of alternative decisions, policies etc. Weaknesses of Neoclassical Economic History 1) Rigour comes at the expense of over simplification and narrowness of analysis 2) Topics are examined because of the existence, estimation or generation of ‘relevant’ data and not because of their historical importance Norrie Synthesis of Approaches - this is best articulated in the first edition of our textbook where he states that the frame work adapted is sufficiently formal to structure the presentation of the historical material, yet sufficiently general not to distort the presentation of events. We present, first, an accounting framework, designed to capture the various interdependencies of the economy and to relate them to economy-wide aggregates such as gross national product. Here, we do nothing more than make more of the formal links and interdependencies that are very much the stuff of traditional economic history. The second addition is a set of simple behavioural relationships for economic agents, customized to represent a small open economy. Put simply, we introduce the general notion that economic decisions represent the outcome of conscious maximizing calculations by consumers, firms, exporters, migrants, and international investors, subject to all the political, social, and economic constraints they face. This approach represents the spirit, if not the specific techniques, of the new economic history. Ever since the Nobel Prize-winning work of the American economist W. Leontief, it has been standard practice to represent an economy by means of a simple input-output framework such as that depicted in Figure 1.1 below. The figure is best understood by looking first at the individual blocks numbered 1 through 4 and then at the figure as a whole.’ Source: Textbook (1st edition), pp 7 24 - Figure 1.1 has four (4) blocks Block 1 - the interindustry matrix which represents transactions between producers (i.e. business to business sales) - across a row, the entries record the value of outputs that are used as intermediate inputs in other sectors - down a column, the entries record the value of output that is purchased by a single sector from other sectors Block 2 - expenditure on goods and services in final form - represents the total final demand or aggregate demand (AD) for each sectors output Block 3 - records the contribution of primary factor inputs in the production process Block 4 Gross Domestic Product = Gross National Expenditure Other Features of an I/O Table The behaviour of economic agents and the determination of various outcomes of their general equilibrium approach are also stated 25 Overall, an idealized economy of this type is really a collection of numerous separate but interconnected markets. Individuals make purchases in one market with an eye to what might be obtained elsewhere, and firms hire an input only after considering what substitutes are available. Sellers of goods or of factors of production look at conditions in their current markets, considering all the while whether it might be profitable to shift production or labour services or investment elsewhere. Changes in demand or in supply on one market spill over into others, and these induced effects, in turn, flow back into the first one. Nor are the interdependencies limited to product markets. Output decisions in product markets depend on the remuneration that primary factors expect, yet these very rates depend on the demand for the factors, which depends on conditions in the product markets. Much effort has been expended by theorists to show, first, that, if certain technical conditions are met, there is, for this idealized economy, a set of prices at which all markets are simultaneously in equilibrium; and second, that the economy will move toward this set of values, if it is not at them already. Essentially the adjustment relies on the assertions that prices will change to remove excess demands or excess supplies in individual markets; that adjustments in one sector feed into all others, and that these adjustments, in turn, feed back on the original sector; and that this sequence of adjustments is stable.’ Source: Textbook (1st edition), pp 13 Modification of an I/O Framework to Canada - Canada has always been closely integrated into other larger economies and ‘This historical fact means we have to modify the general model to make it represent the structure of a small open economy. For product markets, this requirement can be met by asserting that, for all intents and purposes, Canada can take the international economic environment as given….. The main implication of these features of a small open economy is that the adjustment process is constrained to operate in a particular fashion. Changes in prices account for less of an adjustment in markets for traded goods and services; changes in quantities, for more. Likewise, excess demands or supplies for capital are more likely to be resolved by changes in the quantity of transfers from abroad, and less likely, by a response in domestic savings rates. The internal adjustment that does result is centred more obviously in the nontraded sectors, meaning that swings in prices and incomes in these activities are more pronounced. Vague as 26 these observations may be at this point, they will figure prominently in much of the political-economy discussion below.’ Source: Textbook (1st edition), pp 14-15 I/O Table and the Staples Model ‘It is interesting to note just how this approach compares to that traditionally employed in Canadian economic history – the venerable staples theory. It is easily seen that the staples theory is really only a special case of the more general framework outlined above. Staples are export products of one particular type – one row in the figure, so to speak. The backward, forward, and the final-demand linkages associated with staples are, again, one particular set if interdependencies. The impulses to aggregate growth coming from staples trade are but one type of shock that can set the general adjustment process into motion.’ Source: Textbook (1st edition), pp 16 Module 1.10 : Business History Alfred Chandler – Founder of the Organizational School of American Historians 1) Strategy and Structure: Chapters in the History of the American Industrial Enterprise - examined the hierarchial, organizational structures of industrial firms: (I) Du Pont (II) General Motors (III) Standard Oil (IV) Sears Roebuck 2) The Visible Hand: The Managerial Revolution in American Business - the main determinants of organizational innovation were not found in social or political settings but in the technological imperatives of mass production and distribution made possible by the utilization of new sources of energy and the increasing application of scientific knowledge to industrial technology - it was little affected by public policy, capital markets or entrepreneurial talents 27 - the central dynamic that created new organizational capabilities was the investment in production, distribution and management technologies Three Stage Model of Industrial Development 1790-1840 - no new economic institutions or revolutions in business methods occurred - the central theme was the increasing functional specialization made possible by market expansion as described by Adam Smith 1840-88 - triad of epochal advances in railroads, telegraphs and anthracite coal created managerial revolution in transportation and distribution system before spreading to industrial firm 1880 – 1910 - rise of modern industrial firm - the key to business success was the three pronged investment in production; distribution and management technologies 3) Scale and Scope: The Dynamics of Industrial Capitalism Core Concepts -extensive industry-by-industry series of emerging industrial giants - the strategic and organizational choices made by managers shape, if not determine, markets (i.e. their structure, behaviour and performance). - technological advances were capital and scale dependent and required organizational innovations to exploit them - industrial success required I) Investment in large-scale production facilities to achieve the cost advantages scale and scope 28 II) Investment in product-specific marketing, distribution and purchasing networks III) Recruit and develop unique professional management skills to supervise and coordinate function activities and allocate resources 29