* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download 1 THE MINISTRY OF HIGHER AND SECONDARY SPECIAL

Survey

Document related concepts

Old Norse morphology wikipedia , lookup

Zulu grammar wikipedia , lookup

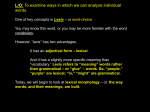

Lexical semantics wikipedia , lookup

Lithuanian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Navajo grammar wikipedia , lookup

Polish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Word-sense disambiguation wikipedia , lookup

Comparison (grammar) wikipedia , lookup

Symbol grounding problem wikipedia , lookup

Ojibwe grammar wikipedia , lookup

Turkish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Untranslatability wikipedia , lookup

Contraction (grammar) wikipedia , lookup

Compound (linguistics) wikipedia , lookup

Esperanto grammar wikipedia , lookup

Classical compound wikipedia , lookup

Agglutination wikipedia , lookup

Pipil grammar wikipedia , lookup

Transcript