THE HURWITZ THEOREM ON SUMS OF SQUARES BY LINEAR

... forces dim U = n/2 to be even by Lemma 2.1, so n must be a multiple of 4. This eliminates the choice n = 6 and concludes the proof of Hurwitz’s theorem! We stated and proved Hurwitz’s theorem over C, but the theorem goes through with variables in R too. After all, if we have an n-term bilinear sum o ...

... forces dim U = n/2 to be even by Lemma 2.1, so n must be a multiple of 4. This eliminates the choice n = 6 and concludes the proof of Hurwitz’s theorem! We stated and proved Hurwitz’s theorem over C, but the theorem goes through with variables in R too. After all, if we have an n-term bilinear sum o ...

Solutions to Math 51 First Exam — April 21, 2011

... for C(A); we can thus eliminate from further consideration all such sets in the above list. We’re left to consider the three remaining three-element sets of column vectors listed above. Now, recall that according to a result from Chapter 12 of the text, a three-element subset of a three-dimensional ...

... for C(A); we can thus eliminate from further consideration all such sets in the above list. We’re left to consider the three remaining three-element sets of column vectors listed above. Now, recall that according to a result from Chapter 12 of the text, a three-element subset of a three-dimensional ...

Contents Euclidean n

... Notice that we now have the concept of both length and angle for even though we don't have the familiar geometry of 2-space and 3-space. In particular, we have a criterion to test whether or not two vectors are orthogonal: if and only if ...

... Notice that we now have the concept of both length and angle for even though we don't have the familiar geometry of 2-space and 3-space. In particular, we have a criterion to test whether or not two vectors are orthogonal: if and only if ...

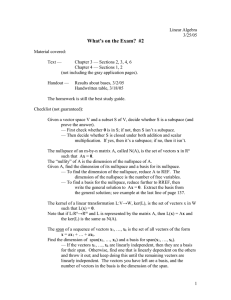

What`s on the Exam - Bryn Mawr College

... Note that if L:Rn→Rm and L is represented by the matrix A, then L(x) = Ax and the ker(L) is the same as N(A). The span of a sequence of vectors x1, …, xk is the set of all vectors of the form x = ax1 + … + axk. Find the dimension of span(x1, …, xk) and a basis for span(x1, …, xk). — If the vectors x ...

... Note that if L:Rn→Rm and L is represented by the matrix A, then L(x) = Ax and the ker(L) is the same as N(A). The span of a sequence of vectors x1, …, xk is the set of all vectors of the form x = ax1 + … + axk. Find the dimension of span(x1, …, xk) and a basis for span(x1, …, xk). — If the vectors x ...

Lecture 14: Section 3.3

... R2 . Show that the vector n1 = (a, b) formed from the coefficients of the equation is orthogonal to the line, that is, orthogonal to every vector along the line. Solution. If (x, y ) is a point on the line ax + by = 0, then (a, b) · (x, y ) = 0. It means that (a, b) is orthogonal to vectors (x, y ) ...

... R2 . Show that the vector n1 = (a, b) formed from the coefficients of the equation is orthogonal to the line, that is, orthogonal to every vector along the line. Solution. If (x, y ) is a point on the line ax + by = 0, then (a, b) · (x, y ) = 0. It means that (a, b) is orthogonal to vectors (x, y ) ...

Cross product

In mathematics and vector calculus, the cross product or vector product (occasionally directed area product to emphasize the geometric significance) is a binary operation on two vectors in three-dimensional space (R3) and is denoted by the symbol ×. The cross product a × b of two linearly independent vectors a and b is a vector that is perpendicular to both and therefore normal to the plane containing them. It has many applications in mathematics, physics, engineering, and computer programming. It should not be confused with dot product (projection product).If two vectors have the same direction (or have the exact opposite direction from one another, i.e. are not linearly independent) or if either one has zero length, then their cross product is zero. More generally, the magnitude of the product equals the area of a parallelogram with the vectors for sides; in particular, the magnitude of the product of two perpendicular vectors is the product of their lengths. The cross product is anticommutative (i.e. a × b = −b × a) and is distributive over addition (i.e. a × (b + c) = a × b + a × c). The space R3 together with the cross product is an algebra over the real numbers, which is neither commutative nor associative, but is a Lie algebra with the cross product being the Lie bracket.Like the dot product, it depends on the metric of Euclidean space, but unlike the dot product, it also depends on a choice of orientation or ""handedness"". The product can be generalized in various ways; it can be made independent of orientation by changing the result to pseudovector, or in arbitrary dimensions the exterior product of vectors can be used with a bivector or two-form result. Also, using the orientation and metric structure just as for the traditional 3-dimensional cross product, one can in n dimensions take the product of n − 1 vectors to produce a vector perpendicular to all of them. But if the product is limited to non-trivial binary products with vector results, it exists only in three and seven dimensions. If one adds the further requirement that the product be uniquely defined, then only the 3-dimensional cross product qualifies. (See § Generalizations, below, for other dimensions.)