Chemical Dynamics at Surfaces

... – as well as the modern experimental methods used to probe the limits of this understanding. ...

... – as well as the modern experimental methods used to probe the limits of this understanding. ...

Chemistry

... metal from their ores, making pottery and glazes, fermenting beer and wine, making pigments for cosmetics and painting, extracting chemicals from plants for medicine and perfume, making cheese, dying cloth, tanning leather, rendering fat into soap, making glass, and making alloys like bronze. The ge ...

... metal from their ores, making pottery and glazes, fermenting beer and wine, making pigments for cosmetics and painting, extracting chemicals from plants for medicine and perfume, making cheese, dying cloth, tanning leather, rendering fat into soap, making glass, and making alloys like bronze. The ge ...

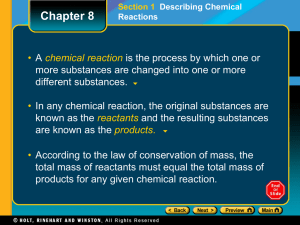

chemical reaction

... • To complete the process of writing a correct equation, the law of conservation of mass must be taken into account. • The relative amounts of reactants and products represented in the equation must be adjusted so that the numbers and types of atoms are the same on both sides of the equation. • This ...

... • To complete the process of writing a correct equation, the law of conservation of mass must be taken into account. • The relative amounts of reactants and products represented in the equation must be adjusted so that the numbers and types of atoms are the same on both sides of the equation. • This ...

mc_ch08 - MrBrownsChem1LCHS

... • To complete the process of writing a correct equation, the law of conservation of mass must be taken into account. • The relative amounts of reactants and products represented in the equation must be adjusted so that the numbers and types of atoms are the same on both sides of the equation. • This ...

... • To complete the process of writing a correct equation, the law of conservation of mass must be taken into account. • The relative amounts of reactants and products represented in the equation must be adjusted so that the numbers and types of atoms are the same on both sides of the equation. • This ...

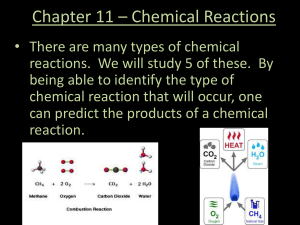

Section 2 Types of Chemical Reactions

... • Carbon is already balanced in the equation. • Two additional hydrogen atoms are needed on the right side of the equation. • Now increase the oxygen atoms by placing the coefficient 2 in front of the molecular formula for oxygen. The correct chemical equation, or balanced formula equation, for the ...

... • Carbon is already balanced in the equation. • Two additional hydrogen atoms are needed on the right side of the equation. • Now increase the oxygen atoms by placing the coefficient 2 in front of the molecular formula for oxygen. The correct chemical equation, or balanced formula equation, for the ...

TEKS 8 - UNT College of Education

... materials are made and the original material disappears. A chemical change could involve molecules attaching to each other to form larger molecules, molecules breaking apart to form two, or more, smaller molecules, or rearrangement of atoms within molecules. In order to make transformations possible ...

... materials are made and the original material disappears. A chemical change could involve molecules attaching to each other to form larger molecules, molecules breaking apart to form two, or more, smaller molecules, or rearrangement of atoms within molecules. In order to make transformations possible ...

Section 1 Describing Chemical Reactions Chapter 8

... • To complete the process of writing a correct equation, the law of conservation of mass must be taken into account. • The relative amounts of reactants and products represented in the equation must be adjusted so that the numbers and types of atoms are the same on both sides of the equation. • This ...

... • To complete the process of writing a correct equation, the law of conservation of mass must be taken into account. • The relative amounts of reactants and products represented in the equation must be adjusted so that the numbers and types of atoms are the same on both sides of the equation. • This ...

Chapter 19 Chemical Thermodynamics

... First Law of Thermodynamics • You will recall from Chapter 5 that energy cannot be created nor destroyed. • Therefore, the total energy of the universe is a constant. • Energy can, however, be converted from one form to another or transferred from a system to the surroundings or vice versa. Chemica ...

... First Law of Thermodynamics • You will recall from Chapter 5 that energy cannot be created nor destroyed. • Therefore, the total energy of the universe is a constant. • Energy can, however, be converted from one form to another or transferred from a system to the surroundings or vice versa. Chemica ...

Balancing Chemical Reactions

... the law of conservation of mass must be taken into account. • The relative amounts of reactants and products represented in the equation must be adjusted so that the numbers and types of atoms are the same on both sides of the equation. ...

... the law of conservation of mass must be taken into account. • The relative amounts of reactants and products represented in the equation must be adjusted so that the numbers and types of atoms are the same on both sides of the equation. ...

Chapter 19 Chemical Thermodynamics

... by both enthalpy and entropy. • Gibb’s Free Energy is a thermodynamic function that combines enthalpy and entropy. • For a reaction occurring at constant pressure and temperature, the sign of Gibb’s Free Energy relates to the spontaneity of the ...

... by both enthalpy and entropy. • Gibb’s Free Energy is a thermodynamic function that combines enthalpy and entropy. • For a reaction occurring at constant pressure and temperature, the sign of Gibb’s Free Energy relates to the spontaneity of the ...

Diversity-oriented synthesis - David Spring

... The sequencing of the human genome has led to scientists achieving a greater understanding of life, at a molecular level, than ever before.1 With these new insights have come new and formidable challenges; one of the most significant is the annotation of the human genome. Meeting this challenge would ...

... The sequencing of the human genome has led to scientists achieving a greater understanding of life, at a molecular level, than ever before.1 With these new insights have come new and formidable challenges; one of the most significant is the annotation of the human genome. Meeting this challenge would ...

ppt

... First Law of Thermodynamics • You will recall from Chapter 5 that energy cannot be created nor destroyed. • Therefore, the total energy of the universe is a constant. • Energy can, however, be converted from one form to another or transferred from a system to the surroundings or vice versa. Chemica ...

... First Law of Thermodynamics • You will recall from Chapter 5 that energy cannot be created nor destroyed. • Therefore, the total energy of the universe is a constant. • Energy can, however, be converted from one form to another or transferred from a system to the surroundings or vice versa. Chemica ...

Theories in the Evolution of Chemical Equilibrium: Impli

... In 1850 Williamson (16), studying incomplete esterification reactions, was the first scientist to propose a submicroscopic model in order to explain the “static” state of chemical equilibrium. He did not consider this equilibrium as a situation in which nothing happens; on the contrary, he assumed t ...

... In 1850 Williamson (16), studying incomplete esterification reactions, was the first scientist to propose a submicroscopic model in order to explain the “static” state of chemical equilibrium. He did not consider this equilibrium as a situation in which nothing happens; on the contrary, he assumed t ...

Chapter 19 Chemical Thermodynamics

... • Energy can, however, be converted from one form to another or transferred from a system to the surroundings or vice versa. Chemical Thermodynamics ...

... • Energy can, however, be converted from one form to another or transferred from a system to the surroundings or vice versa. Chemical Thermodynamics ...

Chemical Reaction

... When things burn they react with oxygen in the air and energy is released as heat and light. ...

... When things burn they react with oxygen in the air and energy is released as heat and light. ...

LESSON 23: Exploding Bags

... Classification of Matter section of CEF’s Passport to Science Exploration: The Core of Chemistry. • Additional information on chemical reactions can be found in the Chemical Reactions section of CEF’s Passport to Science Exploration: ...

... Classification of Matter section of CEF’s Passport to Science Exploration: The Core of Chemistry. • Additional information on chemical reactions can be found in the Chemical Reactions section of CEF’s Passport to Science Exploration: ...

L2004-01A

... technology. Unlike earlier robotic fish, which needed remote controls, they will be able to navigate independently without any human interaction. Rory Doyle, senior research scientist at engineering company BMT Group, which developed the robot fish with researchers at Essex University, said there we ...

... technology. Unlike earlier robotic fish, which needed remote controls, they will be able to navigate independently without any human interaction. Rory Doyle, senior research scientist at engineering company BMT Group, which developed the robot fish with researchers at Essex University, said there we ...

The Chemist - American Institute of Chemists

... school and tertiary education forums. This new vision for chemical education should be closely aligned with the roadmap for the future development of chemistry, as incorporated in the United Nations charter on the International Year of Chemistry (IYC) announced in 2011 [11]. This charter identified ...

... school and tertiary education forums. This new vision for chemical education should be closely aligned with the roadmap for the future development of chemistry, as incorporated in the United Nations charter on the International Year of Chemistry (IYC) announced in 2011 [11]. This charter identified ...

Chemical Technology - Engineers Institute of India

... cost of sulfur produced. Uses of coal is being considered for pilot plant development in India. The question of using pulverized coal directly in the smelter burners or working with secondary combustion gases after ash has been removed must be resulted. ...

... cost of sulfur produced. Uses of coal is being considered for pilot plant development in India. The question of using pulverized coal directly in the smelter burners or working with secondary combustion gases after ash has been removed must be resulted. ...

FoundationsofChemistryppt

... Explaining Chemical Reactions (cont.) • The formulas to the left of the arrow represent the reactants—the substances present before the reaction takes place. • The formulas to the right of the arrow represent the products—the new substances present after the reaction. • The arrow indicates that a r ...

... Explaining Chemical Reactions (cont.) • The formulas to the left of the arrow represent the reactants—the substances present before the reaction takes place. • The formulas to the right of the arrow represent the products—the new substances present after the reaction. • The arrow indicates that a r ...

Chapter 8

... Objectives • Define and give general equations for synthesis, decomposition, single-displacement, and doubledisplacement reactions. • Classify a reaction as a synthesis, decomposition, single-displacement, double-displacement, or combustion reaction. • List three kinds of synthesis reactions and six ...

... Objectives • Define and give general equations for synthesis, decomposition, single-displacement, and doubledisplacement reactions. • Classify a reaction as a synthesis, decomposition, single-displacement, double-displacement, or combustion reaction. • List three kinds of synthesis reactions and six ...

Formation of amorphous silica surface layers by

... Chemical weathering experiments in the laboratory are generally carried out at conditions that promote the chemical breakdown of minerals, namely in chemically dilute solutions at far-from-equilibrium conditions. Moreover, in order to reproduce natural chemical weathering conditions, experiments are ...

... Chemical weathering experiments in the laboratory are generally carried out at conditions that promote the chemical breakdown of minerals, namely in chemically dilute solutions at far-from-equilibrium conditions. Moreover, in order to reproduce natural chemical weathering conditions, experiments are ...

the powerpoint

... Compare the physical properties of metals and nonmetals. Physical properties of metals include: • Luster—Having a shiny surface or reflecting light brightly • Conductors—Heat and electricity move through them easily • Malleable—Ability to be hammered into different shapes • Ductile—Ability to be dr ...

... Compare the physical properties of metals and nonmetals. Physical properties of metals include: • Luster—Having a shiny surface or reflecting light brightly • Conductors—Heat and electricity move through them easily • Malleable—Ability to be hammered into different shapes • Ductile—Ability to be dr ...

Role of Chemistry in Everyday Life

... moment; that we ourselves are beautiful chemical creations and all our activities are controlled by chemicals. The principles of chemistry have been used for the benefit of mankind..Foods we eat have to do with chemistry. They consist of organic compounds like carbohydrates starch and sugar, protein ...

... moment; that we ourselves are beautiful chemical creations and all our activities are controlled by chemicals. The principles of chemistry have been used for the benefit of mankind..Foods we eat have to do with chemistry. They consist of organic compounds like carbohydrates starch and sugar, protein ...

Destruction of Syria's chemical weapons

The destruction of Syria's chemical weapons began with several international agreements that were arrived at with Syria, with an initial destruction deadline of 30 June 2014. United Nations Security Council Resolution 2118 imposed on Syria responsibilities and a timeline for the destruction of its chemical weapons and chemical weapons production facilities. The Security Council resolution incorporated and bound Syria to an implementation plan enacted in an Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) Executive Council Decision. On 23 June 2014, the last declared chemical weapons were shipped out of Syria for destruction. The destruction of the most dangerous chemical weapons began at sea aboard the Maritime Administration Ready Reserve Force vessel CAPE RAY crewed with U.S. civilian merchant mariners. It took 42 days aboard ship to destroy 600 metric tons of chemical agents that would have been used to make deadly Sarin and Mustard Gas.The impetus toward destroying Syria's chemical weapons began with a 9 September 2013 rhetorical suggestion by U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry that Syria turn over all of its chemical weapons within a week. At the time, the U.S. and France headed a coalition of countries on the verge of carrying out air strikes on Syria in response to the 21 August 2013 Ghouta attacks. The suggestion received a positive response from Russia and Syria, and U.S.–Russian negotiations led to the 14 September 2013 ""Framework for Elimination of Syrian Chemical Weapons,"" which calls for the elimination of Syria's chemical weapon stockpiles by mid-2014. Following the agreement, Syria acceded to the Chemical Weapons Convention and agreed to apply that convention provisionally until its entry into force on 14 October 2013. On 21 September, Syria ostensibly provided a list of its chemical weapons to the OPCW, before the deadline set by the framework.On 27 September, the Executive Council of the OPCW adopted a decision, ""Destruction of Syrian Chemical Weapons,"" a detailed implementation plan based on the U.S./Russian agreement. Later on 27 September, the UN Security Council unanimously passed United Nations Security Council Resolution 2118, incorporating the OPCW plan and making it binding on Syria. A joint OPCW-UN mission will supervise the destruction or removal of Syria's chemical arms, while its Director-General is charged with notifying the Executive Council regarding any delay in implementation. The Executive Council would decide whether the non-compliance should be reported to the Security Council, which is responsible for making certain Syria fulfills its commitments under Resolution 2118.OPCW began preliminary inspections of Syria's chemical weapons arsenal on 1 October 2013, and actual destruction began on 6 October. Under OPCW supervision Syrian military personnel began ""destroying munitions such as missile warheads and aerial bombs and disabling mobile and static mixing and filling units."" The destruction of Syria's declared chemical weapons production, mixing, and filling equipment was successfully completed by 31 October deadline. The destruction of the chemical weapons fell well behind schedule. The entire chemical weapons stockpile had been scheduled to be completely removed from the country by 6 February 2014. Only on 23 June 2014, had Syria finished shipping the remaining declared chemicals. On 18 August 2014, all of the most toxic chemicals had been destroyed offshore. Western officials such as British Ambassador Mark Lyall Grant have expressed concerns about the completeness of Syria's disclosures, and believe the OPCW mission should remain in place following the removal of chemical weapons until verification tasks can be completed.Chlorine, a common industrial chemical, is outside the scope of the disarmament agreement; however, its use as a poison gas would violate the Chemical Weapons Convention, which Syria joined in 2013. Various parties, including Western governments, have accused Assad of conducting illegal chlorine attacks in 2014 and 2015. A late disclosure in 2014 regarding Syria's ricin program raised doubts about completeness of the government's declaration of its chemical weapons stockpile, and in early May 2015, OPCW announced that inspectors had found traces of sarin and VX nerve agent at a military research site in Syria that had not been declared previously by the Assad regime.