* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download insearch_pg_38

Survey

Document related concepts

Origins of Rabbinic Judaism wikipedia , lookup

Jewish views on religious pluralism wikipedia , lookup

Index of Jewish history-related articles wikipedia , lookup

Jewish religious movements wikipedia , lookup

History of the Jews in Vancouver wikipedia , lookup

Independent minyan wikipedia , lookup

Jewish schisms wikipedia , lookup

Bereavement in Judaism wikipedia , lookup

History of the Jews in Gdańsk wikipedia , lookup

Hamburg Temple disputes wikipedia , lookup

Romaniote Jews wikipedia , lookup

The Reform Jewish cantorate during the 19th century wikipedia , lookup

Hurva Synagogue wikipedia , lookup

Transcript

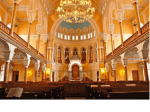

in Search of the Synagogue Part IV Two Distinctive Finds Change Our Conception of Jewish Art & History [3rd century c.e.–7th century c.e.] A continuing conversation with LEE I. LEVINE, professor of Jewish History and Archaeology at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem What is known about Diaspora synagogues in the 3rd–7th centuries? We’ve found many synagogue inscriptions or funerary inscriptions referring to synagogue officials. In contrast, the archaeological evidence is woefully fragmentary, and works written by Jews in the post-70 era are virtually nonexistent. Of the estimated hundreds of Diaspora communities from this time, we have remains of only twelve synagogue buildings, and another nine sites of questionable identification. Which of the twelve synagogue buildings is the best preserved? The best-preserved synagogue building known to date comes from the frontier town of Dura Europos, located on the banks of the Euphrates River in eastern Syria. Discovered in 1932, and dating from the early third century C.E., it was initially a private home converted into a synagogue whose sanctuary was completely remodeled and the number of rooms significantly expanded in the mid-third century. The most sensational aspect of this building is its art. All four walls were covered from floor to ceiling with frescoes depicting a wide range of biblical scenes—Jacob’s dream, the rescue of baby Moses, the exodus from Egypt, Ezekiel’s vision of the dry bones, episodes from the stories of Elijah and the Scroll of Esther, the return of the ark from the Philistines, the Wilderness Tabernacle and Solomon’s Temple, and more. Above the Torah shrine, in the middle of the western wall oriented toward Jerusalem, is a representation of the Jerusalem Temple, flanked by a menorah, lulav, and etrog on the left, and a scene of the Akedah (the binding of Isaac) on the right. Above them are depictions of Jacob blessing his sons and grandsons, David (resembling Orpheus) enchanting animals with his music, and, at the top, a man (the Messiah?) sitting on a throne surrounded by an entourage. What’s the significance of this find? The Dura Europos discovery was one of the crucial factors in sparking an awareness of and renewed interest in ancient Jewish art. Beforehand, and in some circles even to this day, popular opinion maintained that Jews don’t “do” visual art. Dura and other archaeological finds of the twentieth century, some of which were discussed in the previous installment, have done much to disprove this view. When the Dura murals first came to light, it was generally assumed that the art of this synagogue was but the tip of the iceberg. Surely, this small community could not have created such a sophisticated display; it must have copied pictorial models from other, much larger, Diaspora communities. Yet, since that discovery seventy-six years ago, nothing even remotely comparable has been found in the Diaspora or in Israel. Although it may be only a matter of time before another such synagogue comes to light, many scholars have come to the conclusion that the Dura synagogue art may be sui generis, created under the influence of local models. Indeed, the dozen or so pagan temples, and even the nearby church (to date, the oldest ever found), were similarly decorated, though none was as lavish or as extensive as the synagogue. The Dura synagogue is extraordinary in other ways as well. How so? No other site offers such a vivid example of a synagogue in the context of other religious buildings. The Dura synagogue was clearly in harmony with the architectural and artistic ambience of the city. Just as a statue or pictorial depiction of the deity in his/her sacred enclosure was the focus of every local pagan temple, so, too, was the Torah scroll the focus of the Dura synagogue, placed in an aedicula (a small shrine composed of columns supporting a pediment, considered by many as the Jewish equivalent of a pagan statue). Just as pagan temples had a series of enclosures or courtyards leading up to the holy area in the building, so, too, did the synagogue. And just as the Mithraeum (the temple to the eastern god Mithras) and the church displayed scenes from the life of their deity on the walls, so, too, did the synagogue’s frescoes of biblical scenes showing God’s might in saving the people of Israel. Finally, just as other religious sanctuaries had rooms for meeting and feasting, so, too, the Dura synagogue was equipped with ancillary rooms to serve a variety of communal purposes. Was Dura Europos the largest Diaspora synagogue in this period? No. While the Dura synagogue was unique in its art, displaying a remarkable array of biblical themes and Jewish symbols, the distinction of size and rich epigraphic finds belongs to the monumental Sardis synagogue in Asia Minor (today’s Turkey), which featured an 80–yard-long sanctuary with a 20–yard-long atrium-courtyard. Discovered in 1962, the structure, prominently located at an important intersection on the city’s main street, was once a wing of an enormous municipal gymnasium and bath complex. Used first as a synagogue in the third century and then refurbished and redecorated in the fourth, the buildings continued to function for almost three centuries, until the city was captured and destroyed by the Persians in 616 C.E. Entering the building from one of the streets to the east or south, visitors would have found themselves in an open courtyard-atrium lavishly decorated with a mosaic pavement of multicolored geometric patterns and surrounded by porticoes. In the center of the atrium stood a large and impressive marble basin for washing and perhaps drinking. Mention of a “fountain of the Jews” in a municipal inscription may refer to this basin. Three portals—a large central door flanked by two smaller ones—led from the courtyard into the main sanctuary. Just inside, on the eastern wall facing Jerusalem and flanking the main entrance, were two aediculae set on masonry platforms, at least one of which held the Torah scrolls; the second one may have been for other Torah scrolls, a large menorah, or a seat for a congregational leader. A stunning mosaic floor decorated with impressive and intricate geometric designs was divided into seven different patterns. The lower parts of the walls were revetted with marble panels, often bearing inscriptions; the upper parts featured panels of brightly colored marble inlay. Inside the sanctuary, at the western end of the hall, opposite the entrance, was a massive stone table with two large Roman eagles engraved in relief on its two supporting stones. Flanked by two pairs of lions, each sitting back to back, this table was undoubtedly used during the Torah-reading ceremony and may have been where the prayer leader stood. Nearby were three semicircular benches where synagogue leaders presumably sat. No traces of a balcony or other stone benches were found; other members of the congregation likely sat on mats or wooden benches. What can you tell us about the Sardis synagogue inscriptions? Of the eighty-six inscriptions, seventy-nine of them are in Greek and seven in Hebrew. The Hebrew ones are fragmentary; often the only recognizable word is Shalom. With rare exception, the Greek inscriptions were dedicatory in nature, honoring the thirty or so donors who contributed to the building. This corpus reveals to us the large proportion of municipal and imperial officials, almost a third, who were members of or identified with this synagogue. Also, some inscriptions mention converts to Judaism (referred to in Greek as theosebeis), or those who were drawn to the synagogue but did not fully convert. From the Dura Europos and Sardis examples, it seems that, architecturally speaking, Diaspora synagogues of the period had little in common. This is very true. Diaspora synagogues were markedly different from one another in their architectural styles, since each was heavily influenced by the regnant styles of the surrounding area, as has been the case throughout history. Synagogues differed in their size and shape as well as in their location within a city. Some were centrally situated, others peripherally. Some had an atrium; others did not. In some communities, the sanctuary was part of a larger complex that might have included a kitchen, a triclinium (dining hall), or a meeting/study hall. Some buildings had dining halls, which may signify the importance of communal meals; this is also indicated at Dura Europos by the discovery of parchment fragments containing what appears to be a form of Birkat haMazon (Grace after Meals). Some synagogues housed a library; in fact, St. Jerome (d. ca. 420 C.E.) reported that on a visit to Rome in 384 C.E., he met a Jew (Hebraeus) carrying many books or scrolls (volumina) he borrowed from the synagogue. Differences are also evident in artistic decorations. Some synagogues were very conservative in their interpretation of the biblical Second Commandment and chose to decorate their buildings without figural representation; others were more liberal in this regard. What, then, did all these synagogues have in common? All Diaspora synagogues served as community centers for their respective congregations; the Torah shrine was the centerpiece in all synagogue sanctuaries; all Torah shrines (although architecturally different from each other) were placed on the wall facing Jerusalem; and all prominently featured Jewish symbols, especially the menorah. In addition, many, though not all, synagogues made provisions for purification practices, discernible by the presence of basins, fountains, wells, or mikva’ot (ritual baths) in courtyards or entranceways. Such purity concerns may have been a factor in situating many Diaspora synagogues (e.g., Delos, Ostia) as well as Palestinian ones (Gaza, Caesarea) near bodies of water. It seems that at this time the practice of Diaspora Judaism was not very different from that of Palestinian Judaism. We are poorly informed about the religious practices at this point in time, but yes, the archaeological remains do indicate a high degree of similarity. Both in Palestine and the Diaspora, synagogues were often referred to as “holy” (and on occasion “the most holy”) places; most displayed artistic work; virtually all made use of Jewish symbolism; and almost all are oriented toward Jerusalem. Were non-Jews in the Diaspora involved with local synagogues? Very much so. One literary source from late fourth-century Antioch in Syria and two inscriptions from fourth- and fifth-century Aphrodisias in Asia Minor (Turkey) indicate the serious involvement of Christians in synagogues. In Antioch, a local preacher (and later the famous Patriarch of Constantinople), John Chrysostom, railed against many members of his church for regularly attending synagogue services on Sabbaths, holidays, and especially the High Holidays. Christians also went to the synagogue on other days for healing and taking sacred oaths. One inscription from Aphrodisias also notes several converts and non-Jewish sympathizers who participated in a group dedicated to study, prayer, and helping the poor. What else have we learned from the discovery of these Diaspora synagogues? They offer an important corrective to the commonly held opinion that, with the advent of Constantine and the triumph of Christianity in the fourth century and thereafter, Jews suffered from the virulent anti-Jewish legislation of the Byzantine-Christian government and the intense hatred of many church fathers. It was thought that Jewish life had sunk into the oblivion of the Middle Ages, as Jews were faced with nothing but oppression and suppression. Without denying the reality of this picture, it no longer appears to be the whole story. In the first place, it is not at all clear how much influence the imperial legislation and church sermons had on the populace as a whole throughout the empire. Secondly, the archaeological remains point to a number of Jewish communities that seem to have flourished and lived peacefully, if not in total harmony, with their neighbors. One begins to question how effective the anti-Jewish and anti-Judaism rhetoric and laws actually were, and whether the overwhelmingly negative picture we once had of this era is indeed accurate. While we’ve learned a lot from these remains, there is one question that totally eludes us: Where did these synagogues and their communities go after the seventh century? We know nothing about them; they seem to have disappeared from the historical record. Did the Jews convert? Did they migrate elsewhere? Did they continue to exist in these communities, and is it just a fluke that we know nothing about them? I am hopeful that new discoveries and future research will shed light on this enigma. Next Installment: Women in the Ancient Synagogue Before the Dura Europos discovery, popular opinion maintained that Jews don’t “do” visual art. Left: A view of the Western Wall fresco in the Dura Europos Synagogue, Syria. All four walls of the synagogue were covered with frescoes from floor to ceiling. Below: Abraham detail from the Western Wall fresco, Dura Europos Synagogue. Right: Torah shrine detail from the Western Wall fresco, Dura Europos Synagogue. Below: Inside the sanctuary of the Sardis Synagogue. The stone table, engraved with Roman eagles on its two supporting stones and flanked by two pairs of lions sitting back to back, was used during the Torah-reading ceremony. It may have been where the prayer leader stood.