* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Document

Survey

Document related concepts

Memphis, Egypt wikipedia , lookup

Thebes, Egypt wikipedia , lookup

Egyptian temple wikipedia , lookup

Rosetta Stone wikipedia , lookup

Egyptian language wikipedia , lookup

Index of Egypt-related articles wikipedia , lookup

Prehistoric Egypt wikipedia , lookup

Ancient Egyptian race controversy wikipedia , lookup

Mastaba of Hesy-Re wikipedia , lookup

Middle Kingdom of Egypt wikipedia , lookup

Military of ancient Egypt wikipedia , lookup

Khnumhotep and Niankhkhnum wikipedia , lookup

Ancient Egyptian religion wikipedia , lookup

Ancient Egyptian funerary practices wikipedia , lookup

Transcript

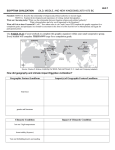

Chapter 3 Pharaohs and the Afterlife: The Art of Ancient Egypt NotesNearly 2500 years ago, the Greek historian Herodotus wrote, “Concerning Egypt itself I shall extend my remarks to a great length, because there is no country that possesses so many wonders, or any that has such a great number of works that defy description.” The greatness of Egypt began more than 3000 years before the birth of Christ and left the world a profusion of great and spectacular monuments cut from stone that symbolized the timelessness of their world. The solemn and ageless art of the Egyptians expresses the unchanging order that, for them, was divinely established. The history of Egypt was known from references in the Old Testament, Greek and Roman writers, and from a history of Egypt written in Greek in the third century AD by an Egyptian high priest named Manetho. It was he who divided the succession of Pharaohs into dynasties that are not deemed entirely accurate. At the end of the 18th century, when Europeans rediscovered Egypt, it became the first subject of archaeological exploration. In 1799, Napoleon’s men discovered the now famous Rosetta stone that gave scholars the key to deciphering Egyptian hieroglyphics. This was the beginning of the new field of Egyptology. Predynastic and Early Dynastic Periods The ancient Egyptians began the history of their kingdom with the unification of Upper (the Southern, upstream part of the Nile Valley that is a narrow tract of grassland that encouraged hunting) and Lower Egypt (The Northern downstream part of the Nile, where the rich soil of the Nile Delta islands encouraged agriculture and animal husbandry). The Palette of King Narmer is one of the earliest historical (verses prehistorical) artworks that have been preserved. It was once thought to commemorate the foundation of the first of Egypt’s 31 dynasties around 2920 BC. Instead of happening as one event, scholars believe it happened over several centuries. The Palette of Narmer reflects the ancient Egyptian belief that the creation of the “Kingdom of the two lands” was a single great event. The palette is an elaborate, formalized version of a utilitarian object commonly used in the Predynastic period to prepare eye makeup. (Egyptians used makeup to protect their eyes against irritation and the glare of the sun.) Narmer’s palette is important not only as a document making the transition from prehistorical to the historical period in ancient Egypt but also as a blueprint of the formula for figure representation that characterized most Egyptian art for 3000 years. At the top of each side of the palette are two heads of the goddess Hathor, represented as a cow with a women’s face. Between the Hathor heads is a hieroglyph giving Narmer’s name within a frame representing the royal palace, making Narmer’s Palette the earliest existing labeled work of historical art. What is important is the characterization of the king as supreme, isolated from and larger than ordinary men and solely responsible for the triumph over the enemy. Here, at the beginning of Egyptian history, is evidence of the Egyptian convention of thought, of art, and of state policy that established the pharaoh as divine ruler. Narmer’s Palette is exceptional among Egyptian artworks because it is commemorative rather than funerary in nature. Portraying the Human Figure The artist’s portrayal of Narmer on both sides of the palette combines profile views of his head, legs, and arms with from views of his eye and torso. This same approach also characterized Mesopotamian art and some Stone Age paintings. Although the proportions of the human figure changed, the method of its representation became standard. The Palette of King Narmer established the basic laws that governed most Egyptian art for millennia. In earlier works figures were often placed haphazardly with out any type of ground line to anchor the figures. On Narmer’s Palette, the sculpture subdivided the surface into registers and inserted the pictorial elements into their organized setting in a neat and orderly way. The horizontal lines separating the narratives also define the ground supporting the figures. This approach was also favored in the ancient Near East. Egyptian artists who departed from this compositional scheme did so deliberately, usually to express the absence of order, as in a chaotic battle scene. Architecture Tombs and the Afterlife Egyptian tombs provide the principle, if not exclusive, evidence for the historical reconstruction of Egyptian civilization. The standard tomb type in early Egypt was the Mastaba. The mastaba (Arabic for “bench”) was a rectangular brick or stone structure with slopping sides erected over an underground burial chamber. Although originally housing single burials they were later used for multiple family members. The interior chambers were various sizes and purposes. Walls were often decorated with colored relief carvings and paintings of scenes from daily life intended to magically provide the deceased with food and entertainment. Mummification The Egyptians believed that from birth a person was accompanied by a kind of other self, the ka or life force, which on the death of the body, could inhabit the corpse and live on. For the ka to live securely, the body had to remain as nearly intact as possible. To insure the Egyptians developed the technique of embalming (mummification), to a high art. The Egyptians did not attach any special significance to the brain. But they left in place the heart, necessary for life and regarded as the seat of intelligence. Preserving the deceased's body by mummification was only the first requirement for immortality in ancient Egypt. Food and drink also had to be provided as did clothing, utensils and furniture. Nothing that had been enjoyed on earth was lacking. Statuettes called ushabtis (answers) were placed in the tomb to perform any labor required by the deceased in the afterlife. Beginning in the Old Kingdom, images of the dead, sculpted in the round and placed in shallow recesses, were also set up in the tomb. They were meant to guarantee permanence of the persons’ identity by providing substitute dwelling places for the ka in case the mummy disintegrated. Wall paintings and reliefs recorded the recurring round of human activities. The Egyptians hoped and expected that the images and inventory of life, collected and set up within the protective stone walls of the tomb would ensure immortality. The First Pyramid One of the most renowned figures in Egyptian history is Imhotep, the royal builder for King Djoser (Reigned 2630-2611 BC) of the Third Dynasty. Imhotep was a man of legendary talent who served also as the pharaoh’s chancellor and high priest of the sun god. After his death, the Egyptians revered Imhotep as a god, and in time may have inflated the list of his achievements. His is the first recorded name of an artist in history. The historian Manetho states that Imhotep designed the Stepped Pyramid of Djoser at Saqqara, the ancient necropolis (GK “City of the Dead”) for Memphis, Egypt's capital at the time. Built before 2600 BC, it is one of the oldest stone structures in Egypt and in its final form, the first truly grandiose royal tomb. It began as a large mastaba, with each of its faces oriented toward one of the cardinal points of the compass. The tomb was enlarged at least twice before taking on its ultimate shape. About 200 feet high, the Stepped Pyramid seems to be a series of mastabas of diminishing size stacked on top of one another to form a structure similar to the great ziggurats of Mesopotamia. Unlike the ziggurats, Djoser’s pyramid is a tomb, not a temple platform, and its dual function was to protect the mummified king and his possessions and to symbolize, by its gigantic presence, his absolute and godlike power. Beneath the pyramid was a network of underground galleries resembling a palace. It was to be Djoser’s new home in the afterlife. Djoser’s tomb is one of many structures arranged around several courtyards located in an enclosed area called a precinct. Some of the buildings are dummy buildings filled with gravel, sand, and rubble. The buildings imitated in stone masonry various types of temporary structures made of plant stems and mats erected in upper and Lower Egypt to celebrate the Jubilee Festival that perpetually reaffirmed the royal existence in the hereafter. The transition into stone of structural forms previously made out of plants may be seen in the long entrance corridor to Djoser’s funerary precinct. There, columns that resemble bundles of reeds project from shot spur walls on either side of the once roofed and dark passageway. A person walking in the passage would soon emerge into a large courtyard and the brilliant light of the Egyptian sun facing Djoser’s pyramid. The columns flanking the pathway resemble later Greek columns. Architectural historians have little doubt today that the buildings of ancient Egypt had a profound impact on the designers of the first Greek stone columnar temples. The columns in Djoser’s complex are the first appearance of stone columns in the history of architecture. The Old Kingdom The Old Kingdom begins with the first pharaoh of the Fourth Dynasty, Sneferu (2575 - 2551 BC). Although tradition places Djoser at the end of the Third Dynasty as the beginning of the Old Kingdom, it ended with the demise of the Eighth Dynasty around 2134 BC. Architecture The three great pyramids, built in the course of about 75 years, represent the culmination of an architectural revolution that began with the mastaba. The new form probably developed, not out of necessity, but from the influence of Heliopolis, the seat of the powerful cult of Re whose emblem was a pyramid stone, the ben-ben. The pyramids are symbols of the sun. The texts inscribed on the walls of many royal tombs beginning with the Fifth Dynasty, refers to the sun’s rays as a ramp the pharaoh uses to ascend to the heavens. The pyramids were where Egyptian kings were reborn in the afterlife, just as the sun was reborn each day at dawn. As with Djoser’s Pyramid, the four sides of each of the Great Pyramids are oriented to the cardinal points of the compass. But the funerary temples associated with the three Gizeh pyramids are not placed on the North side, facing the stars of the Northern sky, as was Djoser’s Temple. The temples sit on the east side, facing the rising sun and underscoring their connection with Re. Beside the causeway and dominating the valley temple of Khafre, raises the Great Sphinx. Carved from a spur of sandstone in an ancient quarry, the colossal statue the largest in the ancient Near East - is probably an image of Khafre, although some think it is of Khufu and was carved before the construction of Khafre’s complex. Who ever it portrays, the Sphinx - a lion with a human head - was associated with the sun god and therefore an appropriate image for a pharaoh. The composite form combines human intelligence with the awesome strength and authority of the king of beasts. Sculpture Sculptors created images of the deceased to serve as abodes for the ka should the mummies be destroyed. Though other materials were used, the primary material for funerary statuary was stone. The Seated Statue of Khafre is one of a series carved for the pharaoh’s valley temple near the Great Sphinx. The stone is diorite, an exceptionally hard stone from the royal quarries 400 miles to the South. Khafre wears a simple kilt and sits rigidly upright on a throne formed of two stylized lion’s bodies. Intertwined lotus and papyrus plants - symbol of the united Egypt - are carved between the thrones legs. A falcon-god Horus extends his protective wings to shelter the pharaoh’s head. Khafre has a royal false beard fastened to his chin and wears the royal linen nemes headdress with the uraeus cobra of kingship on the front. The headdress covers his forehead and falls in pleated folds over his shoulders. The body is well developed, and flawless with a perfect face, regardless of his actual age and appearance. The Egyptians considered ideal proportions appropriate for representing imposing majesty, and artists used them quite independent of reality. These, and all other generalized representations of the pharaohs, are not true portraits nor are they intended to be. Their purpose was not to record individual features or the distinctive shapes of the bodies, but rather to proclaim the godlike nature of Egyptian kingship. The seated king radiates serenity (very calm and relaxed). The sculptor created this effect, common to Egyptian royal statutes, in part by giving the figure great compactness and solidity, with few projecting, breakable parts. The form manifests purpose: to last for eternity. Khafre’s body is attached to an unarticulated slab that forms the back of the king’s throne. His arms are held close to the torso and thighs, and his legs are close together and connected to the chair by the stone the artist did not remove. The pose is frontal, rigid, and bilaterally symmetrical (the same on either side of an axis). The sculptor suppressed all movement and with it the notion of time, creating an eternal stillness. The seated statute is one of only a small number of basic formulaic types that Old Kingdom sculptors used to represent the human figure. Menkaure and His Wife (Khamerernebty?) Another type is the image of a person or deity standing either alone or in a group. This statute once stood in the valley temple of Menkaure’s pyramid complex at Gizeh. Here to the figures remain wedded to the stone block from which they were carved, and the sculptor used conventional postures to suggest the timeless nature of the substitute homes for the ka. The pose, duplicated in countless other Egyptian statutes, are rigidly frontal with arms hanging straight down and close to his well built body. His hands are clenched into fists with thumbs forward. His left leg is slightly advanced, but no shift occurs in the angle of the hips to correspond to the uneven distribution of weight. Khamerernebty stands in a similar position with her right arm circled around the king’s waist, and her left hand gently placed on his left arm. The frozen stereotypical gesture indicates their marital status. The husband and wife show no emotion or affection and do not look at each other, only into space. Most Egyptian statues were painted Seated Scribe Where is the formula? In the history of art, especially portraiture, it is almost a rule that as a human subject’s importance decreases, formality is relaxed and realism is increased. It is telling that the scribe is shown with sagging chest and a protruding belly. Such signs of age would have been disrespectful and inappropriate in a depiction of an Egyptian god king. The statute of the scribe is not a true portrait either. It is a composite of conventional types. The thin sunken face of the scribe would not be attached to a flabby body. Reliefs and Painted Walls In Egyptian tombs, the deceased were also represented by relief sculpture and in mural painting. Agriculture and hunting are also common subjects in Egyptian tomb art. These activities were associated with providing provisions for the ka in the hereafter and had symbolic overtones as a metaphor for triumph over the forces of evil. In the depiction of figures the artist used the conceptual rather than optical approach, representing what was known to be true of the subject, instead of the random view of it, and showing its most characteristic parts at right angles to the line of vision. This conceptual approach expressed a feeling for the constant and changeless aspect of things and was well suited for Egyptian funerary art The Egyptian Canon Idealized and stiff is typical of figures in Egyptian relief sculpture. Egyptian artists regularly ignored the endless variations in body types of real human beings. Painters and sculptors did not sketch their subjects from life but applied a strict canon or system of proportions, to the human figure. They first drew a grid on the wall. Then they placed various human body parts at specific points on a network of squares. The height of a figure, for example, was a fixed number of squares, and the head, shoulders, waist, knees, and other parts of the body also had a predetermined size and place within the scheme. This approach lasted for thousands of years. Specific proportions might vary from workshop to workshop and change over time, but the principle of the canon persisted. The Middle Kingdom About 2150 BC there began a period of more than a century of civil unrest and near anarchy. In 2040 BC the Pharaoh in Upper Egypt, Mentuhotep II (2050-1998 BC) managed to reunite Egypt again under the rule of a single king and established the so called Middle Kingdom (Dynasties XI-XIV) Sculpture One of Mentuhotep II’s successors was Senusret III (1878-1859 BC). His portraits are of special interest because they represent a sharp break from Old Kingdom practice. Although the king’s preserved statues have idealized bodies, the sculptors brought a stunning and unprecedented realism to the rendition of Senusret III’s features. His pessimistic expression reflects the dominant mood of the time and is echoed in Middle Kingdom literature. His portrait is personal, almost intimate, in its revelation of the mark of anxiety that a troubled age might leave on the soul of a king. Architecture The most characteristic burials of the Middle Kingdom are rock-cut tombs. The rock-cut tombs of the Middle Kingdom largely replaced the Old Kingdom mastabas. The 12th Dynasty Tomb of Amenemhet has columns that are nonsupporting because the are carved out of the surrounding rock. The column shafts are fluted with vertical channels in a manner similar to later Greek columns. Archeologists believe fluting derived from the dressing of soft wood trunks with the rounded cutting edge of the adze. Fluted stone columns are yet another case of Egyptian builders’ translating perishable natural forms into permanent architecture. The New Kingdom The Middle Kingdom eventually disintegrated, and power passed to the Hyksos, or shepherd kings who descended on Egypt from Syria and Mesopotamia. They brought with them innovations in weaponry and the horse. Ironically these innovations contributed to their overthrow by native Egyptian Kings of the 17th Dynasty (1600-1550 BC). Ahmose I (1550-1525 BC) was the final conqueror of the Hyksos and the first king of the 18th Dynasty which ushered in the New Kingdom that was the greatest period in Egypt’s long history. At this time, Egypt extended its empire to the Euphrates River in the East deep into Nubia (the Sudan) to the South. A new capital - Thebes, in Upper Egypt - became a great and luxurious metropolis with magnificent palaces, tombs, and temples along both banks of the Nile. Architecture Hatshepsut’s Temple The most impressive monuments of the New Kingdom are its grandiose temples, often built to honor pharaohs and queens, as well as gods. Great pharaonic mortuary temples arose along the Nile near Thebes. These shrines provided the rulers with a place for worshiping their patron gods during their lifetimes and then served as temples to their own honor after their death. The temples were elaborate and luxuriously decorated, befitting both the pharaohs and the gods. The most majestic of these royal mortuary temples, at Deir el-Bahri, was constructed for a female pharaoh Hatshepsut. Some have attributed the temple to Senmut, Hatshepsut’s chancellor, who is described in two inscriptions as royal architect. It was modeled in part on the neighboring Middle Kingdom Temple of Mentuhotep II. Hatshepsut’s temple rises from the valley floor in three colonnaded terraces connected by ramps. It is remarkable how visually well suited the structure is to its natural setting. The long horizontals and verticals of the colonnades and their rhythm of light and dark repeat the pattern of the limestone cliffs above. The colonnade pillars, which are either simply rectangular or chamfered (beveled, or flattened at the edges) into 16 sides, are well proportioned and rhythmically spaced. In Hatshepsut’s day, the terraces were not the barren places they are now but gardens with frankincense trees and rare plants the pharaoh brought from the faraway “land of Put” on the Red Sea. The expedition was prominently recorded on poorly preserved but once brightly painted low reliefs that cover many walls of the complex. The painted reliefs of Hatshepsut’s mortuary temple constituted the first great tribute to women’s achievements in the history of art. Their defacement after her death by the jealous and resentful Thutmose III is therefore especially unfortunate. Over 200 statues of Hatshepsut in various guises were in the tomb complimenting the many reliefs. Thutmose III removed or shattered most of them when he became pharaoh. The statue in our example was thrown into a dump, smashed into many pieces. The statue portrays Hatshepsut as a man holding two globular offerings to the sun god. Other surviving portraits of Hatshepsut represent her with a woman’s breasts. The male imagery is, however, consistent with the queen’s formal assumption of the title of king and the many inscriptions that address her as a man. Ramses II The rock - cut temple of Ramses II is also very impressive. Ramses II (1290-1224 BC) ruled 75 years and was Egypt’s last great warrior pharaoh. The temple was moved nearly 700 feet to its current location to save it from submersion in the Aswan High Damn reservoir. Ramses II proclaimed his greatness by having four colossal statues of himself on the temples facade. The seated figures are almost 12 times the height of the ancient Egyptians. Spectacular as they are, the rock - cut statues sacrifice the refinement of earlier periods for sheer overwhelming size. The interior also displays grand scale statues (32 feet high). The figures of the king are in the guise of Osiris and are carved as one with the pillar, which face each other across a narrow corridor. These pillars have no load-bearing function. The statute column appears throughout art history. Immense Pylon Temples Distinct from the mortuary tombs of the pharaohs are the edifices built to honor one or more of the gods. Successive kings often added to them making them enormous. The Temple of Amen-Re at Karnak was largely the work of 18th Dynasty pharaohs Thutmose I and III, and Hatshepsut. Ramses II of the 19th Dynasty also added some sections. The temple rises from the earth as the original sacred mound rose from the waters at the beginning of time. The New Kingdom pylon temples all had similar plans. Pylon is derived from the simple and massive gateways, or pylons, with sloping walls. The lay out is bilaterally symmetrical along a single axis that runs from an approaching avenue through a colonnaded court and hall into a dimly lit sanctuary. Only Kings and priests were allowed into the sanctuary. The central feature of the New Kingdom pylon temple plan - a narrow axial passageway through the complex - is characteristic of much Egyptian architecture. Hypostyle Halls The dominating feature of statuary lined approach to a New Kingdom temple was the monumental facade of the pylon, which was routinely covered with reliefs glorifying Egypt’s rulers. Inside was an open court with columns on two or more sides, followed by a hall between the court and sanctuary, its long axis placed at right angles to the corridor of the entire building complex. The hypostyle hall (one where columns support the roof) was crowded with massive columns and roofed by stone slabs carried on lintels. The lintels rested on cubical blocks that in turn rested on giant capitals. Egyptian hypostyle halls were built with the central rows of columns higher than those on the sides. Raising the roofs central section created a clerestory. Openings in the clerestory permitted sunlight to filter into the interior, although the stone grills would have blocked much of the light. The clerestory is evidently an Egyptian innovation, and its significance can hardly be overstated. Before the invention of the light bulb, illuminating a buildings interior was always a challenge for architects. The clerestory played a key role, for example, in Roman basilica and medieval church design and has remained an important architectural feature up to the present. In the hypostyle halls at Karnak, the columns are indispensable structurally, unlike the rock-cut tombs, but their function as vertical supports are almost hidden by the horizontal bands of painted sunken relief sculpture. To create the sunken reliefs, the New Kingdom sculptors chiseled deep outlines below the stone’s surface, rather than cut back the stone around the figures to make the figures project from the surface. Sunken reliefs preserve the contours of the columns they adorn. Otherwise the columns would have a irregular, wavy profile. Despite this effort, the overwhelming of the surfaces with reliefs indicates that the architects’ intention was not to emphasize the functional role of the columns. Instead, they used the columns as image and message bearing surfaces. Egyptian columns seem to have originated from an early building technique that used firmly bound sheaves of reeds and swamp plants as roof supports for adobe structures. The transferring of this imagery to stone was first done in Djoser’s funerary precinct at Saqqara. Evidence of Swamp plant origins are still seen in the columns at Karnak, which have bud-cluster or bell-shaped capitals resembling lotus or papyrus (the plants of Upper and Lower Egypt). Sculpture and Painting Extremely popular during the Middle and Old Kingdoms were block statues. In these works the idea that the ka could find an eternal home in the cubic stone image of the deceased was expressed in an even more radical simplification of form than was common in Old Kingdom statuary. This example shows Senmut, Hatshepsut’s chancellor, holding the pharaoh’s daughter by Thutmose II. This was meant to enhance Senmut’s stature through his association with the queen’s daughter as her tutor. The painting technique employed in Egyptian tombs is fresco secco (dry fresco). The paint is applied to plaster that has dried so that the paint is on the surface. Traditional fresco as was practiced in Western Europe is done on wet plaster so that the paint soaks into the plaster making it more permanent. Text is often accompanying the images to amplify the message of the picture and images amplify the text. The frescos often testify to the luxurious life of the Egyptian nobility, filled with good food and drink, fine musicians, lithe dancers, and leisure time to hunt and fish. Akhenaton and the Amarna Period In the mid 14th century, a revolution took place in society and religion. The pharaoh Amenhotep IV, later known as Akhenaton (1353-1335 BC), abandoned the worship of most of the Egyptian gods in favor of Aton, whom he declared to be the universal and only god, identified with the sun disk. He blotted out the name of Amen from all inscriptions and even from his own name and that of his father, Amenhotep III. He emptied the great temples, enraged the priests, and moved his capital down river from Thebes to the site he named Akhenaton (after his new god), where he built his own city and shrines. It is now called Tell el-Amarna. The pharaoh claimed to be both the son and sole prophet of Aton. To him alone could the God make revelation? Moreover, in stark contrast to earlier practice, Akhenaton’s god was represented neither in animal nor in human form but simply as the sun disk emitting life-giving rays. The pharaohs who followed Akhenaton reestablished the cult and priesthood of Amen and restored the temples and the inscriptions. Akhenaton’s brief religious revolution was soon undone, and his new city was largely abandoned. During the brief heretical episode of Akhenaton, however, profound changes occurred in Egyptian art. A colossal statue of Akhenaton from Karnak, toppled and buried after his death, retains the standard frontal pose of canonical pharaonic portraits. The effeminate body, with its curving contours and the long face with full lips and heavy lidded eyes are far different from the heroically proportioned figures of his predecessors. Modern doctors have tried to explain the physique to a variety of illnesses that cannot be agreed upon. The belief that the statue is a realistic portrait of physical deformity is probably faulty. Some historians think the portrait is a deliberate artistic reaction against the established style, paralleling the suppression of traditional religion. They argue that Akhenaton’s artists tried to formulate a new androgynous image of the pharaoh as the manifestation of Aton, the sexless sun disk. But no consensus exists other than that the style was revolutionary and short lived. Nefertiti Nefertiti means “The Beautiful One is Here.” This bust of Nefertiti exhibits the similar expression of entranced musing and an almost mannered sensitivity and delicacy of curving contour. The sculptor, Thutmose, may have been alluding to a heavy flower on its slender stalk by exaggerating the weight of the crowned head and the length of her serpentine neck. The sculptor seems to have adjusted the actual likeness to meet the era’s standard of spiritual beauty. A sunken relief perhaps from a private shrine, undulating curves replace rigid lines, and the figures possess the prominent bellies that characterize figures of the Amarna School. This intimate portrayal of the pharaoh and his family is unprecedented in Egyptian art. King Tut The legacy of the Amarna style mat be seen in the artifacts found in the unplundered tomb of Tutankhamen (1333-1323 BC), who was probably Akhenaton’s son by a minor wife. He ruled for a decade and died at 18. The principal monument in Tut’s collection is the innermost coffin of three. Made of beaten gold (about a quarter ton) and inlaid with semiprecious stones. Inside was the portrait mask of Tutankhamen, one of the most famous pieces of art in the world. Painted Chest Although Tutankhamen was too young to fight, his position as king required that he be represented as a conqueror. Together the two panels are a double advertisement of royal power comparable to the later reliefs adorning Assyrian palaces. The absence of a ground line in an Egyptian painting or relief implies chaos and death. Tut slays the enemy like game, in great numbers. Behind him are three tiers of undersized war chariots, which serve to magnify the king’s figure and to increase the count of his warriors. The themes are traditional, but the fluid, curvilinear forms are features reminiscent of the Amarna style. The Book of the Dead Tutankhamen’s mummy case shows the boy king in the guise of Osiris, god of the dead and king of the underworld, as well as, giver of eternal life. The ritual of the cult of Osiris is recorded in the so called Book of the Dead, a collection of spells and prayers. Illustrated papyrus scrolls, some as long as 70 feet, containing these texts were the essential equipment of the tombs of well to do persons. This scroll is of Hu-Nefer, the royal scribe and steward to pharaoh Seti I, and was found in his tomb in the Theban necropolis. This illustration represents the final judgment of the deceased. At the left, Anubis, the jackal headed god of embalming, leads Hu-nefer into the hall of judgment. The god then adjusts the scales to weigh the dead man’s heart against the feather of the goddess Maat, protectress of truth and right. A hybrid monster, Ammit, half hippopotamus and half lion, the devourer of the sinful, awaits the decision of the scales. If weighing has been unfavorable to the deceased, the monster would have eaten his heart. The ibis headed god Toth records the proceedings. Above, the gods of the Egyptian pantheon are arranged as witness, while Hu-Nefer kneels in adoration before them. Having been justified by the scales, Hu-Nefer is brought by Osiris’ son; the falcon headed Horus, into the presence of the green faced Osiris and his sisters Isis and Nephthys to receive eternal life. In Hu-Nefer’s scroll the figures all have a formality of stance, shape, and attitude of traditional Egyptian art. Abstract figures and hieroglyphics alike are aligned rigidly. Nothing here was painted in the flexible, curvilinear style suggestive of movement that was evident in the art of Amarna. Tutankhamen’s return to conservatism is unmistakable.