* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download File - Ethics and Society

Cosmopolitanism wikipedia , lookup

J. Baird Callicott wikipedia , lookup

Divine command theory wikipedia , lookup

Internalism and externalism wikipedia , lookup

Utilitarianism wikipedia , lookup

Immanuel Kant wikipedia , lookup

The Morals of Chess wikipedia , lookup

Bernard Williams wikipedia , lookup

Ethics in religion wikipedia , lookup

Ethics of artificial intelligence wikipedia , lookup

Lawrence Kohlberg wikipedia , lookup

Alasdair MacIntyre wikipedia , lookup

Consequentialism wikipedia , lookup

Morality and religion wikipedia , lookup

Moral disengagement wikipedia , lookup

Moral development wikipedia , lookup

Ethical intuitionism wikipedia , lookup

Lawrence Kohlberg's stages of moral development wikipedia , lookup

Morality throughout the Life Span wikipedia , lookup

Moral relativism wikipedia , lookup

Thomas Hill Green wikipedia , lookup

Moral responsibility wikipedia , lookup

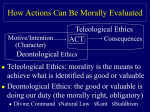

Kantian Ethics Recap The principle of utility At the heart of utilitarian reasoning is the ‘principle of utility’. Also known as ‘the greatest happiness principle’, it tells us that the best action is the one that produces the greatest happiness for the greatest number of people. 2 Recap Strengths of utilitarianism Utilitarianism argues that the purpose of morality is to promote general well-being. It tells us that when we make moral decisions, we have to take into account the interest of other people and give equal weight to the pleasure and pain of everyone affected by our actions. 3 Recap Weaknesses of utilitarianism One trouble with utilitarianism is that different types of happiness are often incompatible (不能作比較). Happiness cannot be measured and calculated easily, nor is it always possible to predict the future consequences of actions. The biggest problem, however, is that utilitarian reasoning is sometimes used to justify actions that are clearly immoral. 4 Recap Rule utilitarianism Instead of applying the principle of utility to actions, we can apply it to moral rules. According to ‘rule utilitarianism’, we should consider the consequences of following various rules and choose to follow the one that is likely to bring about the best outcome for everyone. 5 In this lecture… Our moral duty (道德責任) Categorical imperative (定言律令) Universal law (普世道德律) Dignity (尊嚴) and respect (尊重) Criticisms of Kant’s ethics 6 A dilemma Suppose you have promised your friend that you will help her with her homework at 3:00pm. As you are on your way to meet her, you see an accident victim lying on the side of the road who desperately needs help. There is no one else around to help the injured victim. 7 A dilemma What should you do: keep the promise to meet your friend, or break the promise so that you can help the injured person? Do you think we must always keep our promises? Can promise breaking be morally justified in this situation? 8 Our moral duty Immanuel Kant 康德 (1724-1804) argued that we have a moral duty (道德責任) to do what is right for its own sake, i.e. we ought to do what is right simply because it is the right thing to do. Immanuel Kant 9 Our moral duty According to Kant, we are rational (理性 的) persons living in a moral community (道德群體) populated by other rational persons. The basic question of morality concerns how we ought to behave based on an understanding of our duty (道德責任) to each other. 10 Our moral duty For Kant, morality is not something we learn from our parents or teachers, nor do we learn to distinguish right from wrong by observing other people’s actions. Rather, reason 理性 (i.e. our ability to think logically) tells us what we ought or ought not to do. 11 Our moral duty Reason enables us to understand our relationship with other people as well as the moral duty we have to each other. In Kantian ethics, ‘duty’ can be defined as what we ought to do as rational persons (i.e. as members of the moral community). 12 Our moral duty It is through reason that we come to know our duty, i.e. what each and every rational person ought to do. Since morality is founded on (建基於) reason, everyone, except small children and the mentally disabled (精神病患者), should be able to distinguish right from wrong. 13 Our moral duty As you might remember, utilitarianism holds that happiness or pleasure is the only thing that is intrinsically good (i.e. good or valuable it itself). Thus, according to utilitarian reasoning, any action that promotes overall happiness is morally right. 14 Our moral duty Kant rejected utilitarian reasoning by drawing attention to the fact that some pleasures (e.g. that of the rapist 強姦者 or torturer 施虐者) are immoral and therefore bad. In Kant’s view, the only thing that is good in itself is a person’s ‘good will’ (i.e. good intention 良好意圖). 15 Our moral duty ‘Good will’ can be understood as the intention (意圖) to perform one’s duty for its own sake (i.e. to do what is right simply because it is the right thing to do). For Kant, a good will (or good intention) is a necessary element of any morally good action. 16 Our moral duty According to Kant, someone acts with a good will when he or she performs an action simply because he or she knows that it is the right thing to do (i.e. that he or she has a duty to do it). 17 Our moral duty According to Kant, some actions have moral worth 道德價值 (i.e. moral value), other actions do not. For Kant, a good will is what makes an action ‘moral’. Only when we act from good will does our action have moral worth. 18 Our moral duty Brushing your teeth may be the right thing to do, but it has no moral worth because it has nothing to do with ‘good will’ or ‘duty’. Offering help to other people, on the other hand, is an action that has moral worth if you are motivated to do so by a good will or a sense of duty. 19 Our moral duty Consider the following examples: 1. “I like helping people because I expect them to return the favor (投桃報李).” 2. “I like helping people because it makes me feel good about myself.” 20 Our moral duty In these examples, although helping people is right, the actions have no moral worth because they are not done with the right intention (意圖) or motive (動機). From the standpoint of Kantian ethics, it is not enough that we do the right thing; we must do the right thing for the right reason. 21 Our moral duty Actions motivated by self-interest or desire do not have moral worth because self-interest and desire often lead us to do bad or wrong things. Morality, in Kant’s view, has nothing to do with selfish motives (自私的動機), but everything to do with duty and good intention. 22 Our moral duty Do the following actions have moral worth? 1. “I build a school for poor children because I want the school to be named after me (以我命名).” 2. “I build a school for poor children because that is the best I can do to help them.” 23 Our moral duty Finally, Kant argued that if an action is right, we have a duty to do it no matter the consequences. Consequences, in his view, are irrelevant when we make moral judgments or decisions. If we have a duty to do something, we ought to do so even if it might lead to bad consequences. 24 Categorical imperative How do we distinguish right from wrong? Are there any rules or principles (原則) that we can follow when we make moral judgments or decisions? 25 Categorical imperative Kant believed that there are universal (普世的、適用於所有人的) moral rules that all rational persons have a duty to follow. We can use reason to work out a set of absolute (絕對的) moral principles. To do so, we have to start with the question: ‘What ought I to do?’ 26 Categorical imperative Kant observed that the meaning of the word ‘ought’ is confusing (使人混淆) in everyday language. It is therefore necessary to distinguish between hypothetical ‘ought’ (which is non-moral) and categorical ‘ought’ (which is moral). 27 Categorical imperative Kant made a clear distinction (區分) between two different kinds of imperatives; namely, ‘hypothetical imperatives’ (假言律令) and ‘categorical imperatives’ (定言律令). An ‘imperative’ is a command (指令) that tell us what we ought to do. 28 Categorical imperative A hypothetical imperative tells us what we ought to do to get what we want. For example: ‘If you want a good job, get a good education.’ ‘If you want to arrive on time, you ought to leave early.’ 29 Categorical imperative A categorical imperative, on the other hand, tells us what is the morally right thing to do. For example: ‘You ought to keep your promise.’ ‘You ought not to torture (虐待) innocent people.’ 30 Categorical imperative To sum up, a hypothetical imperative 1. specifies a means (手段) to an end (目的); 2. is always in the form of a conditional sentence; 3. is about satisfying a goal or desire; and 4. has nothing to do with ‘morality’. 31 Categorical imperative In contrast, a categorical imperative 1. specifies what everyone has a duty to do as a moral person; 2. is not in the form of a conditional sentence (duty is ‘unconditional’ 無條件的) 3. has nothing to do with satisfying goals or desires; and 4. is the basis of universal moral law (普世道 德法則). 32 Categorical imperative There are two formulations of the categorical imperative: 1. the formula of universal law (普世道德律) 2. the formula of humanity as an end in itself (以人為本) 33 Universal law For Kant, morality is based in reason (理性). At the heart of Kantian ethics is a system of universal moral laws (普世道 德律), i.e. moral rules or principles (法則) that every rational (理性的) person would agree to. The same moral standards apply to everyone. Every rational person is expected to follow the same moral rules. 34 Universal law The formula of universal law: When we are judging whether an action is morally right or wrong, we must ask ourselves whether we would rationally (理 性地) want and expect everyone to act in that way (by putting ourselves in other people’s shoes). If the answer is ‘yes’, the action is moral. If the answer is ‘no’, the action is immoral. 35 Universal law Consider this example: Suppose you need some money and you want to borrow it from your friend. Would it be moral to make a promise to repay (償 還) it without really intending to do so? Do you rationally want and expect everyone to act in this way? 36 Universal law No. If everyone acted in this way, no one would believe in promises anymore. It would not be possible to borrow money because no one would lend money to others, knowing that promises would not be kept and loans would not be repaid. No one would take promises as promises if they were meant to be broken. 37 Universal law Consider a different situation: Suppose you need some money. You want to borrow it from your friend by making a sincere (真誠的) promise to repay it. Is it moral to do so? Do you want and expect everyone to act in that way? 38 Universal law Yes. Reason (理性) tells us that doing so is moral because we would want and expect everyone to act in that way. To sum up, making a sincere promise is moral, whereas making a lying promise is immoral. 39 Universal law ‘Making a sincere promise’ is a universal law because we can expect every rational person to act in that way. Reason tells us that it is the morally right thing to do. ‘Making a lying promise’ cannot be a universal law because we cannot rationally expect everyone to act in that way. Therefore, it is wrong to do so. 40 Universal law Do you think the following can be considered as ‘universal moral laws’? 1. Steal from other people those things that you cannot afford to buy. 2. Shout at waiters in restaurants. 3. Avoid polluting the environment. 41 Dignity and respect Kant’s concept of respect for persons (尊重個人) is derived from the formula of humanity as an end in itself (以人為 本): ‘Never use other people merely (純粹地) as a means (手段) to your own ends (目的).’ 42 Dignity and respect The belief that people ought to be regarded as having the highest intrinsic value is central to Kant’s ethics. The dignity (尊嚴) of being human arises from the fact that humans exist for goals and purposes of their own. As such, they must be respected as ‘ends in themselves’ (自為目的). 43 Dignity and respect Objects (物件) do not have intrinsic value. Why? Because they cannot make choices and therefore do not exist for purposes of their own. We can use objects for our ends (i.e. goals and purposes) because they do not have purposes of their own. In Kant’s view, it is not immoral to do so. 44 Dignity and respect For example, a pen does not exist for a purpose of its own; instead, it exists to serve a human purpose, i.e. to be used as a tool for writing. The pen is not an ‘end in itself.’ It has no intrinsic value (內在價值); it only has instrumental value (利用價值), i.e. to be used as a means (手段) to an end (目的). 45 Dignity and respect Human beings are not objects. They have intrinsic value, or ‘dignity’ (尊嚴), because they can make choices and set goals for themselves. Unlike objects, humans exist for purposes of their own. They can choose what they want to do. That is why we have a duty to respect persons as ends in themselves. 46 Dignity and respect According to the formula of humanity as an end in itself, it is necessary for us to respect a person’s dignity. It is wrong to treat persons as objects, i.e. as mere means (純粹手段) to our own ends. For Kant, it is not necessarily immoral to treat a person as a means as long as we do not treat them as objects. 47 Dignity and respect For example, in hiring a taxi I employ the driver to get me to where I want, thereby making use of him. But I do not treat him as an object because I also recognize his purpose of making a living by getting people to their destinations (目的地). 48 Dignity and respect Why is it morally wrong to treat other people as objects? It is because when we do so, we fail to see that other people do not exist to serve our purposes. When we force others to do things that they are unwilling to do, we fail to respect them as ends in themselves. 49 Dignity and respect Unlike objects, persons have dignity because they can set goals for themselves. As such, persons are valuable in themselves, whether or not they are useful for others. To sum up: because persons are not objects, it is immoral to treat humans in the same way we treat objects. 50 Criticisms of Kant’s ethics One objection to Kant’s moral theory is that it cannot cope with conflicts (衝突) of duty. Consider the following dilemma (兩難處境): Suppose you are considering stealing food from a supermarket to feed you starving (挨餓的) children. You do not want to do it, but you cannot think of any other ways to feed your children. What should you do? 51 Criticisms of Kant’s ethics There are two relevant moral rules in this situation: [1] ‘You should not steal’, and [2] ‘You should not allow your children to starve.’ Now the question becomes: If there is a conflict between these two moral rules, which one should you follow? 52 Criticisms of Kant’s ethics Kantian ethics has also been criticized for being too rigid (僵化). For Kant, moral laws are absolute commands of reason (理性的絕對指令). In other words, they must be upheld (堅 持) at all times. If reason tells that we have a duty to do something, we ought to do it no matter the consequences. 53 Criticisms of Kant’s ethics For example, Kant argued that it is wrong to lie under all circumstances. There was even one example in which Kant himself suggested that if a killer came to the door asking for someone hiding inside whom he wanted to kill, we ought to tell him the truth. 54 Criticisms of Kant’s ethics Consider the following situation: The year is 1942. You are an ordinary German citizen. In your home you are hiding an innocent Jewish woman named Sarah, who is fleeing (逃避) Nazi officers. When the Nazis knock on your door and ask if Sarah is in your house. What should you do? Should you tell the truth or lie? 55 Criticisms of Kant’s ethics Suppose, in the above example, because you told the murderers the truth, they found their victim and killed her. You would be blameless (無須負責) from a Kantian point of view, i.e. you would not be responsible for the victim’s death. 56 Criticisms of Kant’s ethics Why? Because consequences, in Kant’s view, are irrelevant when we make moral judgments or decisions. For Kant, since we have a moral duty to tell the truth, we are not responsible for any bad consequences that might follow as a result of doing so. 57 Criticisms of Kant’s ethics Can we escape responsibility so easily? After all, we helped the murderers find their victim. Do you think that there is something wrong with Kant’s reasoning? 58 Criticisms of Kant’s ethics Most people would find Kant’s reasoning highly unsatisfactory (難以令 人滿意). Some may go further and argue that under the given circumstances, we have a duty to lie because there is no better way to save the life of an innocent person. 59