* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Wars on land and sea

Survey

Document related concepts

Pontus (region) wikipedia , lookup

Greek contributions to Islamic world wikipedia , lookup

Spartan army wikipedia , lookup

Pontic Greeks wikipedia , lookup

Ancient Greek literature wikipedia , lookup

Greek Revival architecture wikipedia , lookup

Ancient Greek religion wikipedia , lookup

List of oracular statements from Delphi wikipedia , lookup

Corinthian War wikipedia , lookup

Ionian Revolt wikipedia , lookup

Transcript

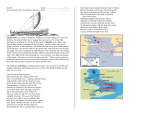

3.8 Wars on land and sea Warfare was a common experience for the Greeks, either as a result of the city-states fighting each other or uniting against a common enemy, such as Persia. This was particularly so in the fifth century BC, and many of Athens s cultural achievements took place in a 50-year period in this century (see source 1). Some of our earliest examples of historical writing came from attempts to understand the reasons behind some of these wars. Source 2 Map showing the sites of the battles of Marathon, Thermopylae and Salamis Persian navy 480 BC Persian army 480 BC Aegean Sea Thermopylae August 480 BC Source 1 Timeline of major Greek wars in the fifth century BC HIST IA Naval battle of Artemisium August 480 BC Euboea Plataea August 479 BC Attica A Marathon 490 BC Athens 400 Salamis Salamis September 480 BC Aegima 410 420 460–400 BC Thucydides 450 460 484–425 BC Herodotus 490 500 BC retroactive 1 445–431 BC A period of peace 457–445 BC Peloponnesian War, stage 1 Sparta and its allies versus Athens and its allies 470 480 76 431–404 BC Peloponnesian War, stage 2 430 440 0 Battle site 480–479 BC Second Persian Invasion, led by King Xerxes 490 BC First Persian Invasion, led by King Darius War on land 20 40 km N the hoplite The Greek soldiers were called hoplites, from the Greek word hoplon, meaning heavy armour , which they wore for protection. The metal helmet had a section in the front to protect the nose and on top was a plume made from horsehair. They wore a leather waistcoat, laced at the front, with iron scales attached; this was lighter than the earlier bronze breastplates and later the leather was replaced by linen. Their lower legs were protected by greaves. The original bronze greaves were replaced in the fifth century BC by leather ones. Their last item of protection was a circular shield made of wood covered with bronze, which was attached to their left arm with a strap. When they went into battle they carried a 2.4 metre spear, which could be used for thrusting or thrown as a javelin, and a short sword for closer fighting. A hoplite fighting alone would not be protected from an attack on his right side, so the Greeks developed a strategic Source 3 An artist s impression of a Greek hoplite formation known as a phalanx. Soldiers stood side by side, holding their shield in their left hand in front of them, which protected their front. It also protected the sword arm of their neighbour to the left. Such disciplined fighting required long periods of training. In Sparta this continued for many years, but in Athens also, at the age of 18, every citizen went through two years of training as an ephebe. War at sea the trireme Greek ships played a crucial role in defending Greece from the Persian attacks. Their first ships with battleships were pentekonters 25 oarsmen on each side but most of these had been replaced by triremes. Triremes were about 35 metres long and 5 metres wide. They had two square sails but during battle they relied on the power of their 170 oarsmen, arranged in three rows on each side of the ship. Rowing together, and kept in time by a piper, they could be driven forward at a speed of 18 kilometres per hour. They had a bronze-sheathed beak just below the waterline and they would ram this into the side of an enemy ship to sink it. Source 4 Modern reconstruction of a Greek trireme. It shows the three levels of oars that powered it and the beak or battering ram at the front. Persian army. However, this only made the Persians more determined to launch a new attack, with much larger forces. This new attack took place ten years later in 480 BC, when the Persian king Xerxes led two armies into Greece one on land and one at sea. Despite brave resistance by the Spartans, the Persians broke through at Thermopylae (see the map and photograph in section 3.2). Then they moved into Athens, destroying much of the city. The leaders of the Greek states decided to try to stop the Persians in the waters around Salamis, an island southwest of Athens. Their strategies were successful and led to a Greek victory. These two battles are studied in more detail in the following section. The Greek naval victory at Salamis in September 480 BC was followed by a victory over the Persian army at Plataea in August 479 BC. The modern marathon is 42.2 kilometres. This is the distance a Greek messenger called Pheidippides ran from Marathon to Athens to tell of the victory over the Persians. He collapsed and died after giving his message. aCTiviTieS CheCk your underSTanding 1 Over time, the ways in which the hoplites protected their chest and legs changed. Describe the changes in (a) how they protected their chest and (b) how they protected their legs. 2 The first Persian Invasion of Greece in 490 BC was launched by sea. What was different about the second invasion by Xerxes ten years later? 3 List the major battles of the Second Persian Invasion in order with the dates of each. uSe The SourCeS 4 Copy source 3 and label the following parts. For each part, describe the materials used. • Helmet • Breastplate • Greaves • Shield 5 From source 4 and the text, describe three features that made the trireme such a powerful fighting weapon. The two wars with Persia Around 490 BC the fate of Greece hung in the balance. The mighty Persian empire launched an invasion to punish cities such as Athens for helping fellow Greeks in the east in a revolt against Persia. In 490 BC in the battle of Marathon on the coast of Attica, the Athenians pushed back an invading phalanx: a tightly packed wall of soldiers, protected by their shields and helmets trireme: Greek ship with three banks of oars ChaPTer 3 | Ancient Greece 77 3.9 Two battles of the Second Persian War Thermopylae — a land battle The Persian king Xerxes launched his second attack in 480 BC. By August his land forces were just north of Attica, while his fleet was moored nearby off the island of Euboea. To enter southern Greece, the Persian army had to pass through a narrow strip of land at Thermopylae, where the mountains came down almost to the sea, leaving a narrow strip of land only about two chariots wide (see section 3.2, source 2, and section 3.8, source 2). The Spartan king Leonidas led a relatively small force of 7000 men, including 300 Spartans, to try to prevent the army of Xerxes entering Greece. They fought valiantly for two days but on the night of the second day the Persians were shown a pass over the mountain that allowed them to bring troops around behind the Greeks. Leonidas sent most of the troops away but he and the 300 Spartans fought valiantly until they were all killed. Source 2 An account of the Battle of Salamis by the Greek historian Herodotus (c.484–425 BC). Herodotus was about four years old when the battle took place and about 50 when he finished this account. The whole fleet now got under way, and in a moment the Persians were on them. The Greeks checked their way and began to back astern; and they were on the point of running aground when Ameinias of Pallene, in charge of an Athenian ship, drove ahead and rammed an enemy vessel. Seeing the two ships . . . locked together, the rest of the Greek fleet hurried to Ameinias’s assistance, and the general action began. . . . There is also a popular belief that the phantom shape of a woman appeared, and in a voice which could be heard by every man in the fleet, contemptuously asked if they proposed to go astern all day, and then cheered them on to fight. The Athenian squadron found itself facing the Phoenicians, who formed the Persian left wing on the western, or Salamis, side of the line. The [Spartans] faced the ships of Ionia, which were stationed on the Piraeus, or eastern, side . . . the Persian fleet suffered severely in the battle . . . because they were ignorant of naval tactics, and fought at random without any proper disposition of their force, while the Greek fleet worked together as a whole; none the less, they fought well that day … 78 Retroactive 1 Salamis — a naval battle Source 1 Map showing the positions of the Greek and Persian fleets before the Battle of Salamis Eleusis Gulf of Eleusis MEGARIS Mt Aegaleos ATTICA Salamis Gulf of Salamis Atlante N 0 Salamis 1 2 km Psyttalea Saronic Gulf Greeks Persians The greatest destruction took place when the ships which had been first engaged turned tail; for those astern fell foul of them in their attempt to press forward and do some service for their king . . . Xerxes watched the course of the battle from the base of Mt Aegaleos, across the strait from Salamis . . . When the Persians . . . were trying to get back to Phalerum, the Aeginetan squadron, which was waiting to catch them in the narrows, did memorable service. The enemy was in hopeless confusion; such ships as offered resistance or tried to escape were cut to pieces by the Athenians, while the Aeginetans caught and disabled those which attempted to get clear . . . Such of the Persian ships as escaped destruction made their way back to Phalerum . . . During the confused struggle in the narrows a valuable service was performed by the Athenian Aristides . . . He took a number of the Athenian heavy infantry, who were posted along the coast of Salamis, across to Psyttalea, where they killed every one of the Persian soldiers who had been landed there . . . From Herodotus: The Histories, translated by Aubrey de Selincourt, Penguin, 1954, pp. 526–30. Piraeus Source 3 Modern artist’s impression of the Battle of Salamis Note how the boat is steered. The rudder had not yet been invented. (Compare with source 2, page 237.) Capsized boat. The rowers on the lowest level were probably most at risk when a boat sank. Source 4 An extract from a play called The Persians by Aeschylus (c.525–450 BC) in which he describes the Battle of Salamis from a Persian point of view The trumpet with its blast fired all [the Greek] line; and instantly, at the word of command, with the even stroke of foaming oars they smote the briny deep. Swiftly they all hove clear into view . . . a mighty shout greeted our ears: ‘On ye sons of Hellas! Free your native land, free your children, your wives, the [temples] of your fathers’ gods, and the tombs of your ancestor. Now you battle for your all.’ . . . It was a ship of Hellas that began the charge and sheared off entire the curved stern of a Phoenician barque. Each [Greek] captain drove his ship straight against some other ship. At first, indeed, the . . . Persian armament held its own; but when the mass of our ships had been crowded in the narrows . . . and each crashed its bronze-faced beak against each of its own line, they [broke] their whole array of oars; while the [Greek] galleys . . . hemmed them in and battered them on every side. The hulls of our vessels rolled over and the sea was . . . strewn . . . with wrecks and slaughtered men. The shores and reefs were crowded with our dead . . . the foe kept striking and hacking them with broken oars and fragments of wrecked ships; and groans and shrieks together filled the open sea until . . . night hid the scene . . . the [Greeks] bounded from their ships and encircled the whole island round about, so that our men were at a loss which way to turn. Oft-time they were struck by stones slung from their hands, and arrows . . . At last the [Greeks], charging with one shout, smote them and hacked to pieces the limbs of the poor wretches, until they had utterly destroyed the life of all. From the Heinemann and Harvard University Press edition of Aeschylus, translated by Herbert Weir Smyth, 1963. Working historically /// Knowing about the author of a source can help in knowing how useful it is. Aeschylus is considered the greatest of the Greek playwrights. Most of his plays, like those of other Greek playwrights, were based on stories from mythology, but The Persians is based on current events. It is thought that Aeschylus fought in the battles at Marathon and Salamis. ACTIVITIES CHECK YOUR UNDERSTANDING 1 Why did the Greeks decide that Thermopylae was a possible site for stopping the Persian advance? 2 How did the Persians manage to trap the Greek army at Thermopylae? 3 What image of the Spartan soldier does the battle present? USE THE SOURCES 4 Carefully read source 2 and source 4. Also refer to source 1, showing where the Greek and Persian ships were positioned at the start of the battle. a Do both accounts tell us whether the Greeks or Persians won the battle? b Identify two ways in which the two accounts differ. c Identify two things that both writers agree on. 5 Carefully study source 3 and identify the details in it that are based on sources 2 and 4. 6 From the information given about Aeschylus and Herodotus at the start of the extracts, and your reading of the two accounts, assess how reliable each account might be. CHAPTER 3 | Ancient Greece 79