* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download The Case of Greece (1960-1989), by E. Ioakimoglou and

Survey

Document related concepts

Economics of fascism wikipedia , lookup

Fei–Ranis model of economic growth wikipedia , lookup

Steady-state economy wikipedia , lookup

Economic growth wikipedia , lookup

Non-monetary economy wikipedia , lookup

Pensions crisis wikipedia , lookup

Marx's theory of alienation wikipedia , lookup

Transformation in economics wikipedia , lookup

Refusal of work wikipedia , lookup

Economic calculation problem wikipedia , lookup

Economic democracy wikipedia , lookup

Transformation problem wikipedia , lookup

Perspectives on capitalism by school of thought wikipedia , lookup

Transcript

Review of Radical Political Economics

Vol. 25(2)81-107(1993)

Capital Accumulation and Over-Accumulation

Crisis: The Case of Greece (1960-1989)

Elias loakimoglou

John Milios

ABSTRACT: In this paper, the concept of capital over-accumulation, formulated by Marx in

Volume 3 of Capital, is discussed and adopted as the theoretical framework for the study of

capital accumulation and economic crisis in Greece in the period 1960-89. The empirical part

of the analysis is based on the investigation of a series of indices which reveal the historical

trend of the social and economic relations determining capital accumulation. It is thus shown

that the main factor determining the economic crisis of Greek capitalism since the late seventies

is the decreasing ability of the capitalist class to economize on constant capital, which is the

outcome of the social relation of forces established in the class-struggle.

INTRODUCTION

Greek capitalism developed with very high growth rates in the post-war

period until the end of the seventies. Among the OECD countries, the

economic performance of Greece in the period 1962-79 compares only with

that of Spain and Japan. However, the high growth rates of Greek capitalism

came to an end in 1980, and have remained low ever since.

The country's per capita Gross Domestic Product (GDP) increased at

constant market prices at an annual rate of 5.8% in the period 1951-60,

7.6% in the period 1961-70,5.6% in the period 1971-75,4.1% in the period

1976-80 and 1.6% in the period 1981-90.

In the 1980s, the rapid decline of the country's GDP growth rates, along

with the deterioration of nearly all other economic indices such as the rate

of investment, the inflation index and employment, made it apparent that

Greek capitalism had entered a period of economic crisis. The discussion

concerning the character and causes of this crisis has not abated.

Conservative economists, as well as officials of the present conservative

government, argue the crisis is a result of the "socialist experiments" of the

previous socialist government, PASOK, (1981-88). They claim that wage

increases and the power gained by trade unions under PASOK rule

undermined the competitiveness of the Greek economy and discouraged

Greek entrepreneurs from investing in their firms. According to the

conservatives, the only way out of the crisis is to liberalize the Greek

economy.

Athens, Greece.

® 1993 Union for Radical Political Economics.

Published by Blackwell Publishers, 238 Main St., Cambridge, MA 02142, USA, and

108 Cowley Rd., Oxford, OX4 1JF, UK.

The majority of progressive or leftist economists, as well a« socialist

politicians, share the opinion that the crisis is a result of the structural

problems of international and Greek capitalism since the late 1970s. They

claim that the harsh, restrictive austerity policy practiced by the present

government merely aggravates the economic problems, reducing demand (the

consumption ability of the working classes) and destroying social consensus.

In our opinion, the economic crisis of Greek capitalism can be adequately

interpreted only from the point of view of Marxist theory, which allows the

consideration of the immanent mechanisms of capital valorization and

accumulation. Without such an approximation to the development of the

(Greek) capitalist economy, any general statement about "structural problems

of capitalism" becomes meaningless. We believe that the Marxian concept

of over-accumulation of capital, developed mainly in Volume 3 of Capital,

enlightens the immanent relations determining the statistically attested

stagnation of the Greek capitalist economy in the 1980s.

In this paper, we begin by presenting and discussing of the Marxian theory

of over-accumulation of capital, which we propose as the interpreting scheme

of the capitalist economic crisis (Section I). We then elaborate the empirical

picture of capital accumulation in Greece during the period 1960-89, using

a series of suitable statistical indices, the development of which also indicates

the developmental trend of the economic relations Marx postulated (Section

II). In this section we also formulate some theoretical conclusions with

regard to the character of both the economic crisis and the economic policy

adopted by the ruling political powers in Greece. These conclusions are

obtained by analyzing the statistical data in relation to the theoretical

premises presented in Section I and can be considered as a verification of

these premises. The statistical data presented in Section II are then used for

a concise periodization of the development of Greek capitalism since 1960,

by briefly referring to the social background (social relation of forces) during

each distinct period of economic performance (Section III).

I. THE CONCEPT OF OVER-ACCUMULATION

CRISIS FROM CAPITAL BY KARL MARX

Karl Marx presents one of his most famous discoveries, the law of the

tendential fall of the profit rate, in Part 3, Volume 3 of Capital. One of the

chapters found in this part refers to the development of the law's internal

contradictions, and includes a section which is entitled "Surplus Capital

Alongside Surplus Population" (Section 3, Chapter 15). In this section Marx

defines an over-accumulation crisis. On comprehending the Marxian

definition of capital over-accumulation, one is forced in one way or another,

to confront the logic of Capital; that is, the internal coherence and the

organization rules of the Marxian logical constructions.

83

It was Gerard Dumenil (1978) who showed that the capital is logically

based upon the distinction between internal and external determinations. One

understands internal determinations as the necessary relations in a given type

of society, which remain unchanged and are constantly present, regardless

of all the changes in historical development. These relations are present even

though they remain hidden beneath the surface of everyday events and the

changes of economic, political or ideological conjuncture. Internal

determinations constitute what Marx defined as the (capitalist) mode of

production. On the contrary, the external determinations constitute the

variety of relations and events which do not originate from the unchanged

structural characteristics of the given type of society (mode of production),

but from the changing mutual strengths in the class struggle of the

antagonistic classes, within one and the same type of class power. For

example, capitalist exploitation and surplus-value extraction are internal

determinations of every capitalist society. The fact that we are dealing with

a capitalist society, though, does not indicate that the working day will be

12, 10 or 7 hours, that the welfare services will be more or less extended,

or that the workers' trade unions will be strong or weak, etc. These last

relations belong to the variety of external determinations (external to the

structural relations that constitute the capitalist mode of production), which

can take on many different forms in different countries, or in the different

historical phases of a capitalist society.

The most valuable element in DumemTs analysis is his study of the way

these two forms of social relations interact with each other. Dumenil showed

that the external determinations do not constitute any violation of the

economic laws arising from the internal determinations, nor are they acting

restrictively or in contradiction to these laws. On the contrary, the external

determinations act only through the necessary internal relations. Their action

therefore, is mediated by the economic laws. The formation of the value of

the labor force, for instance, is not the outcome of two independent factors

acting separately from one another - namely the socially necessary labor time

for the production of the workers' means of subsistence on the one hand, and

the political or trade union strength of the working class on the other. These

two factors do not produce any separate results which can then be added or

mutually revoked. The relations external to the law (the results of the class

struggle) act through the necessary internal relations. The strengthening of

the working class causes an increase in the socially necessary labor time and

therefore an increase in the value of the labor-force.

Our presentation of the capital over-accumulation concept shall therefore

be based on the distinction between internal determinations on the one hand

(which are related to the economic laws), and external determinations on the

other.

The starting point of Marx's analysis is the definition of the absolute

over-accumulation. It can be regarded as a kind of preliminary definition

84

Elias Ioakimoglou and John Milios

which then leads to the definition of the relative over~accuniulttinm. The

absolute over-accumulation refers to a boundary situation, which allows

Marx to formulate a clear and comprehensible definition. (At this point,

Marx adopts a methodology which is common in the natural sciences).

We now follow Marx's definition:

There would be an absolute over-production of capital as soon as no

further additional capital could be employed for the purpose of

capitalist production. But the purpose of capitalist production is the

valorization of capital, i.e. appropriation of surplus labor, production of

surplus-value, of profit. Thus as soon as the capital has grown in such

proportion to the working population that neither the absolute labortime that this working population supplies nor its relative surplus laborvalue can be extended ...; where, therefore, the expanded capital

produces only the same mass of surplus-value as before, there will be an

absolute over-production of capital; i.e. the expanded C+AC will not

produce any more profit, or will even produce less profit, than the

capital C did before its increase by AC. In both cases there would even be

a sharper and more sudden fall in the general rate of profit, but this time

on account of a change in the composition of capital which would not be

due to a development in productivity, but rather to a rise in the money

value of the variable capital on account of higher wages and to a

corresponding decline in the proportion of surp lus labor to necessary

labor. (Marx 1981: 360).

First, a clarification must be made in the above definition. In the case

of capital over-accumulation, the fall in the profit rate is not the result of

a development in the labor-force's productive capacity ( with a

subsequent increase in the organic composition of capital). This

argument is related to the fact that in chapters 13,14 and 15 of the third

volume of Capital, which precede the definition of over-accumulation,

Marx had already formulated and analyzed the law of the tendential fall in

the rate of profit as an outcome connected with the development of the

productive capacity of the labor force. In the definition of absolute over accumulation Marx makes it clear, therefore, that he refers to a fall in

the profit rate determined by factors other than in the case of the law of

the tendential fall. In the case of absolute over-accumulation, it is not the

increase in the labor productivity and the subsequent increase, at an even

higher rate, in the organic c omposition of capital. It is the decline in the

proportion of surplus labor to necessary labor (Marx 1981: 360). In other

words, the determining factor in the fall of the profit rate is now the

decrease in the surplus-value rate. For reasons arising from the history

of the labor and communist movement, this Marxian argument has not

been seriously considered by Marxists, who tend to admonish that every

fall in the profit rate is a result of an increase in the organic composition

of capital.

85

Nevertheless, it is apparent that the profit rate depends on two "variables": the

surplus-value rate on the one hand, and the organic composition of capital

on the other. One should note at this point, that Marx's definition quoted

above seems to take into consideration only the surplus-value rate, that is,

the relation between surplus labor and necessary labor. However, this "onesided" analysis is not due to an omission or a theoretical mistake. It is

connected with the application of an analytical method widely used in the

natural sciences and well-known to Marx. This method is the study of the

change of a specific quantity under the influence of the change of another

quantity, taking into account that all other factors remain constant. The

definition of capital over-accumulation focuses on the influence of changes

in the surplus-value rate (i.e., the rate of exploitation of labor by capital) on

the profit rate, while all other factors, including the organic composition of

capital, are regarded as constant. That is why Marx claims that overaccumulation of capital occurs when:

the capital is unable to exploit labor at the level of exploitation that is

required by the "healthy" and "normal" development of the capitalist

production process (Marx 1981: 364).

The question that now arises is in what way does Marx study the

combined effect of organic composition and surplus-value rate on the profit

rate? Considering the profit rate to be the dependent variable (R), then the

exploitation rate (S/V) and the organic composition of capital (C/V) will be

the independent variables, according to the following relation:

(1

)

where S stands for surplus-value, V for the variable part of capital (value of

labor-force), and C for constant capital (value of the means of production).

As mentioned, Marx studies the influence of S/V on R by considering C/V

as a constant quantity in Section 3, Chapter 15, where he defines overaccumulation. On the contrary, when he elaborates the "nature of the law"

of the tendential fall in the profit rate in Chapter 13, he considers S/V as a

constant quantity. Therefore, he successively studies the influence of the

independent variables on the dependent one, in an effort to cover all possible

cases and factors that determine the change of the dependent variable.

The first assumption is that the organic composition of capital remains

unchanged. This leads Marx to the definition of capital overaccumulation.

His argument with regard to changes in the surplus-value rate is that an

increasing labor demand due to the capital accumulation ("as soon as capital

has grown in such proportion to the working population that..." (op. cit.))

will lead to a falling rate of surplus-value. This is due to the lack of

additional workers (very low unemployment rate) and the subsequent

86

increases of real wages. However, the surplus-value rate depends aim) on

other factors, which Marx does not seem to feel obliged to explain. The

absolute labor time, on the one hand, does not depend exclusively on the

number of workers, but also on the length of the working day. On the other

hand, the relative labor time (i.e., the rate of exploitation) does not only

depend on the wages, but also on the increase in labor productivity. These

"omissions" by Karl Marx concerning the definition of capital overaccumulation can be explained as follows:

* The length of the working day is purely an external relation with regard

to the examined economic law, as we have explained above.

* The labor productivity is regarded as an unchangeable factor, exactly like

the organic composition of capital, the increase of which is "just another

expression for the progressive development of the social productivity of

labor" (Marx 1981:318).

Therefore we are not dealing with omissions in Marx's analysis, but with his

scientific method of abstraction. The economic law does not refer to the

concrete capitalist relations in a given society. It refers to their "kernel," or

inherent elements of their specific structure, having excluded:

a) all the multiple external determinations, which occur in one form or

another, and depending on the changing economic, social and

political conjuncture in a given society, may not even exist.

b) all determinations which are considered temporarily constant, so that

the effects of each "independent variable" on the "dependent

variable" become separately apparent.

The above statements shall now be considered in relation to the concrete

analysis of the concrete reality, which is our final aim.

Obviously the assumption of a constant organic composition of capital shall

be abandoned. This means that when the decrease in the exploitation rate is

being compensated by an even higher decrease in the organic composition

of capital, the profit rate will rise instead of fall.

The following question shall be posed: Under what circumstances does a

decrease in the rate of exploitation, (as Marx described it in Section 3,

Chapter 15, Volume 3 of Capital) lead to a decrease in the profit rate and

to an economic crisis? The same question can also be regarded as part of a

significant problem which was studied by Marx himself: in what way is the

surplus-value rate (rate of exploitation) transformed into profit rate? Marx

deals with this problem in the first part of Volume 3 in Capital. Let us recall

its title: "The transformation of surplus-value into profit, and of the

surplus-value rate into rate of profit."

Let us follow, then, the methodology of Karl Marx. This time we will

consider the surplus-value rate as a constant quantity and deal with the

87

relation between the organic composition of capital and the profit rate. One

could argue that this problem is stated and solved by Marx principally in part

3, Volume 3, and more precisely in Chapter 13. Here he deals with the

famous law of the tendential fall in the profit rate, claiming that the increase

in the productive force of labor causes an increase in the organic composition

of capital and a subsequent decrease in the profit rate. However, the organic

composition of capital depends on a series of factors other than labor

productivity, which are considered here (Chapter 13) as constant quantities.

For this reason, our analysis shall focus its attention on part 1, Volume 3 of

Capital (Chapters 1-7). Let the following relation guide us:

which means that:

where Y is the net product, that is, the sum of surplus-value and value of

labor force (variable capital).

Equation (2) shows that the organic composition of capital C/V can be

analyzed by the rate of surplus value on the one hand, and the quantity C/Y,

on the other. This last quantity expresses the value of constant capital which

is necessary for the production of one unit of product. The increase or

decrease of this quantity illustrates, therefore, the ability of the capitalist

class to spare or economize on constant capital. Marx himself devoted the

whole of chapter 5 to this subject (economy in the use of constant capital).

In this chapter we find the enumeration of all factors related to the ability of

capitalists to economize on constant capital.

Once again, in Chapter 5 of Capital, Marx follows the abstraction method

we described above. He considers that the surplus-value rate is "given" (i.e.,

constant), "in order to avoid needless complications" (Marx 1981: 171). He

then describes the factors which ensure or restrict economy in the use of

constant capital. Let us attempt to summarize the main points of the Marxian

analysis:

a) Lengthening of the workday or work year.

The volume of fixed capital (factory buildings, machinery, etc.)

remains the same, whether work continues for 16 hours or for 12. The

extension of the working day requires no new expenditure on this, the

most expensive portion of the constant capital. (Marx 1981: 170).

b) Concentration of the means of production and employment of them "on

a massive scale" (Marx 1981: 175).

88

c) Socially combined labor (concentration and cooperation of workers,

social character of labor) (Marx 1981: 172).

d) Economy on the conditions of work at the expense of the workers

The contradictory and antithetical character of the capitalist mode of

production leads it to count the squandering of the life and health of

the worker, and the depression of his conditions of existence, as itself

an economy in the use of constant capital, and hence a means for

raising the rate of profit (Marx 1981: 179).

There are, of course, forms of economy in the use of constant capital

connected with an increase in labor productivity:

e) Re-cycling of waste products (Marx 1981: 173-74). Productivity increase

in sector I, (which produces means of production) (op. cit. p. 175).

f) Economy designated by the experience of the collective worker (Marx

1981: 198-199).

g) Economy as a result of the appropriate education of the collective worker

and his subordination to the factory despotism — that is the capitalist

relations of production which are, at the same time, the relations of

power:

The fanaticism that the capitalist shows for economizing on means of

production is now comprehensible. If nothing is to be lost or wasted,

if the means of production are to be used only in the manner required

by production itself, then this depends partly on the workers' training

and skill and partly on the discipline that the capitalist exerts over the

combined workers.... (Marx 1981: 176).

The analysis of Marx shows that the ability of the capitalist class to

economize on constant capital is not a "technical aspect" of the production

process, but an outcome of the social relation of forces, that is a result of

class struggle.

Increasing economy in the use of constant capital presupposes an

increasing power of the capitalist class over the production process itself. It

is often connected with a deterioration of the workers 9 economic and social

status, as Marx showed. On the other hand, economy in the use of constant

capital "concerns the worker as little as a horse is concerned with the

expense of its bit and bridle" (Marx 1981: 178).

The fall in the exploitation rate is transformed into a fall in the profit rate

only in the case where it is not compensated for by economies in the use of

constant capital. On the contrary, an increase in the factor illustrating the use

of constant capital (factor C/Y) over a certain period (i.e., a fall in the

"constant capital efficiency," Y/C) may lead to a fall in the profit rate and

an over-accumulation crisis, even in the instance of a constant or slightly

increasing exploitation rate. An increase in factor C/Y, that is, the declining

89

ability of the capitalist class to economize on constant capital, can again be

the result of either a decrease in (Y/N) or an increase in (C/N), since:

where N is the number of workers, (Y/N) is the "apparent labor

productivity/ assuming that the length of the work year is constant, and

(C/N) is the constant capital intensity.

It is worth mentioning at this point that since the end of the 1970s, the

process of restructuring a capitalist economy through the introduction of

micro-electronic applications in capitalist production (automation of

production), does not aim only to increase labor productivity and thereby the

rate of exploitation. It also aims to economize considerably on the use of

constant capital.

Let us now return to the theory of over-accumulation crisis. The crisis

itself unavoidably results in a fall or deceleration in demand and thereby

leads to an increase in the unemployed production capacity, that is, an

increase of the so-called capital intensity of the capitalist economy.

It is clear, though, that in our theoretical approach we do not consider

under-consumption as the cause of economic crisis but as one of its major

effects, which then produces its own effects in respect to the profit rate; that

is, it feeds back into the crisis. The whole process takes on the form of a

"positive feedback," or a "vicious cycle." In our opinion, this "inner and

necessary connection" between the elements of a capitalist economy in a

conjuncture of over-accumulation crisis is verified by the fact that in many

cases (e.g., Greece), consumption increases during the whole period that

precedes the outbreak of the crisis.

As a conclusion of the above theoretical analysis we can formulate the

following statement:

Over-accumulation crisis is determined by two factors, both being an

eventual outcome of class struggle: a decreasing exploitation rate of labor

and more decisively, a decreasing economy in the use of constant capital.

The investigation, therefore, of the empirically detectable characteristics

of economic crisis in Greece (i.e., the verification that the Greek economic

crisis has the character of an over-accumulation crisis) shall be based on the

combined application of two types of quantitative indices: (a) indices

approaching the rate of labor exploitation, (b) indices approaching factor

C/Y, and thereby the ability of the capitalist class to economize on constant

capital.

90

II. THE EMPIRICAL INVESTIGATION OF THE CRISIS.

INDICES OF CAPITAL ACCUMULATION IN

GREECE (1960-89)

The empirical investigation of capitalist accumulation from the Marxian point

of view is obliged to confront the fact that statistical data does not describe

(or correspond to) the Marxian value-categories, but illustrates some

"superficial phenomena11 of the economic processes. This fact gave rise to

a dispute among Marxian social scientists, as to whether, or to what extent,

empirical reality can be approached by means of a Marxian use or

interpretation of statistical data. In our opinion, the most interesting such

discussion, which is worth mentioning here, is one which took place in W.

Germany during the '70s (Altvater; Hoffmann; Schoeller; Semmler 1974-A

& 1974-B, Diefenbach, Groezinger, Ibsen, Wartenpfuhl, Wengenroth: 1976,

Altvater, Hoffmann, Semmler: 1976, Schoeller: 1976, Busch: 1978).

However, an analysis of this discussion is not required for the purpose of

this paper.

In our opinion, the fact that empirically detectable economic phenomena

are the forms under which the "hidden" structural characteristics of the

capitalist system (the economic laws discovered by Marx) make themselves

apparent (Erscheinungsformen: forms of appearance), allows the use of

carefully selected statistical indices under certain presuppositions. These

indices can be used only as indications with regard to the way economic laws

act in a concrete society and for a concrete historical period. They show the

trend in the development of the value relations.

The indices are then just historical proxies of value categories. As an

example, the real wage is not the value of the labor force. However, an

increase (or decrease) in the average real wages in a certain country over a

historical period indicates a respective increasing (or decreasing) trend in the

value of the labor force (in the given country and for the given historical

period). Our opinion is that Marx's whole analysis shows the conceptual

unity of value categories and their forms of appearance. Otherwise, one

would have to distinguish between the "history of structures" on the one

hand and the "history of events" on the other, as two processes independent

from one another. However, such an assumption contradicts the Marxian

theory.

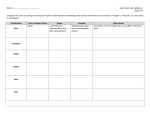

The indices selected for the present investigation are the following:

* The annual Net Output (Y) at market prices (Net Value Added calculated

as the difference between Gross Value Added and the Consumption of

Fixed Capital). The historical change of this index illustrates the trend

of change of the sum variable capital + surplus value.

91

* The annual changes of the Net Value Added (ΔΥ), that is the additional

annual Net Output in comparison with the previous year, e.g., ΔΥ1988

= Y1988 —Y1987.

* The annual Net Fixed Capital Formation (I), which is the Gross Fixed

Capital Formation minus the Consumption of Fixed Capital.

* The so-called "Productivity of Capital" or "Capital Efficiency," that is

the Output/Capital Ratio (Y/K) (Net Product/Fixed Capital Stock). It

shows the net value produced by means of a unit of fixed capital. It also

represents the reverse relation of index (K/Y), the historical change of

which illustrates the ability of capitalists to economize on constant

capital. A decreasing "Capital Efficiency" (increasing index K/Y) means

decreasing economy in the use of constant capital.

* The so-called Marginal "Productivity of Capital," which is the Marginal

Output/Capital ratio (ΔΥ/Ι), that is, the increase of the Net Product per

unit of new Fixed Capital Investment. This index reveals the historical

trend of the ability of new investment to ensure economies in the use of

constant capital.

* The Investment Rate (I/Y).

* The Revenue of Labor or Labor Income (L) (wages and salaries plus

compensation for those who are self-employed and contributions for

social insurance paid by employers) and the average Revenue of Labor

(L/N), that is, the Revenue of Labor over employment.

* The share of Net Value Added going to labor (L/Y). The changes of

(L/Y) in real terms over a time period reveal the historical trend of the

rate of exploitation.

* The Rate of Profit or Rate of Return (R)

which is equivalent to

* The Marginal Rate of Profit (AR) on Fixed Capital

which is equivalent to

that is the change of Profit (ΔΥ-AL) per unit of new Fixed Capital

Investment (I), or the product of the Marginal Profit Quotient (1 ΔL/ΔΥ) and the Marginal Output/Capital ratio (ΔΥ/Ι). This index

illustrates the trend regarding the profitability of new investment.

92

* The Capital Intensity (K/N), which relates the total capital atock K with

the applied labor force N and represents, therefore, an index of the

technical composition of capital.

* The apparent productivity of labor (Y/N), that is, the Net Value Added

over the total employment.

The above indices were calculated both for the Greek economy as a whole,

and for the manufacturing sector. The data was provided by the National

Accounts of Greece. The calculation of the above indices is based on 1980

constant market prices, as well as current prices. The results of the

calculations are presented here for the Greek manufacturing sector in the

form of graphs, but they are also available in the form of tables on IBMcompatible computer diskettes (for Greek manufacturing as well as for the

total economy). 1 We continue by presenting only the graphs of the indices

calculated for the manufacturing sector, for two reasons:

a) The indices calculated for the total economy show exactly the same

trends as the manufacturing indices. Their presentation would not,

therefore, be of any benefit to the paper.

b) Data concerning the manufacturing sector is considered to be more

accurate than data referring to the total economy.

At this point we will comment on the empirical results presented in the

graphs, focusing our attention on the parameters of the economic crisis:

a) As Figure 2 shows, the rate of change of the apparent productivity of

labor (Y/N) lags behind: (i) the growth rate of capital intensity (K/N)

since 1979, and (ii) the rate of change of the average real wage (L/N)

during the period 1973-1985. As a consequence of these developments,

the Output/Capital Ratio (Y/K) in volume falls since 1979 (Figure 4),

while the Labor Share (L/Y) rises in the time period 1973-85 (Figure 3).

It is worth noticing at this point, that an index such as (Y/K) or (R)

calculated in volume, illustrates the changes in the conditions of

accumulation in a better way than the same index calculated in value.

Calculations in value also take into consideration the changes of relative

prices (of consumption products and of capital goods as to the prices of

the net product) induced by market conditions and fluctuations.

It is clear, then, that the decline in the Profit Rate (R) of Greek

manufacturing since 1973 (Figures 6 & 7), can be attributed to the

combined effect of a squeeze on the share of output going to profits

([Y-L]/Y, or 1 - [L/Y]) and an increase in the Capital/Output Ratio

(K/Y). However, in the most recent period since 1985-86, there has been

a deterioration of real wages (Figures 2 & 3). The latter did not lead to

an increase in the Profit Rate (R) (Figures 6 & 7), because of the

continuing fall in the Output/Capital Ratio (Y/K).

93

Nevertheless, the de the net product (increasing profit share) in combination

with the lower decreasing rates of (Y/K) since 1984 resulted in a

stabilization of the Profit Rate calculated in volume, since the same year

(Figure 6). The same parameters significantly boosted the Marginal

Profit Rate (AR), that is the profitability of additional investment, since

1985 (Figure 8). b) The trend of the Rate of Accumulation (I/K), as well

as that of the Net Fixed Capital Formation (I) in Greek manufacturing has

clearly changed from down to up in 1986 (Figure 9). This reversal has

contributed to a stabilization or only a modest increase of the Marginal

Output/Capital Ratio (ΔY/I) (Figure 5).

It is evident from our calculations that the same factors affecting the

profitability in the Greek manufacturing sector also drive the Profit Rate (R)

of the whole Greek economy to low levels. All the phenomena discussed

above in relation to the manufacturing sector can be detected on the level of

the whole Greek economy as well.

These empirical results support the hypothesis of this paper, namely that

the present crisis of Greek capitalism has the character of a capital overaccumulation. To be specific, the rapid fall in the profit rate is mainly the

result of two parameters:

a) The fixed capital stock (K) is increasing in higher rates than the product

00 gained by means of this capital stock. This development has clearly

made itself apparent since 1979 (Figure 4), meaning that Greek

capitalists have failed to economize on constant capital since that time.

In the economical and political conjuncture of the late 1970s and '80s,

the decreasing "capital efficiency" (i.e., the increasing factor K/Y) seems

to constitute the permanent major factor which pushes the profit rate

downwards.

b) The share of wages in the national income cannot be suppressed below

a certain level. This means that the restrictive austerity government

policies face very strong opposition from the working class, which is

more or less succeeding in protecting its standard of living. Furthermore,

Greek workers managed to increase their wages in the seventies and

early eighties, pushing the wage ratio (L/Y) upwards.

As can be seen in Figures 2 & 3, the first phase of increase in real wages

and of the factor L/Y took place in the period 1974-78. This development

was connected with the overthrow of the military dictatorship (1967-74),

which had suppressed the labor movement and decreased the labor share

(L/Y). The restoration of parliamentary democracy is thus related to a

decrease in the exploitation rate of the labor force in Greece (i.e., an

increase in the labor share). This development coincided with stagnant

"capital efficiency" (Y/K), in the period 1974-79. During this period, Greek

capitalists did not succeed in economizing on constant capital any longer, as

94

can be concluded from Figures (4) and (6). The result wan a decreams in the

profit rate of Greek manufacturing (Figure 6).

The role of the banking system was also decisive during this time period.

Following the guidelines of the government's economic policy, it aided

Greek capitalism in facing only a mild crisis until 1979. During the late

1970s the Greek credit system functioned in a way which permitted the

continuation of production of non-profitable plants. This was done by

adopting an inflationary monetary policy. The section of means of production

that in a classic crisis would have to be destroyed continued to operate as

capital, using credit with negative real interest rates. This economic policy

also played an important role in the early 1980s, when the capital efficiency

Y/K of the economy started to fall, thus pushing the profit rate downwards

with higher rates (Figure 6).

The Greek working classes strongly opposed the restrictive austerity policy

adopted by the conservative government from 1979-80, as the crisis of the

economy was becoming apparent. In the 1981 general elections, the

overwhelming majority of the wage earning class voted for the Left (48 % for

the Socialist Party, PASOK, and 13% for the communists), which promised

to follow a policy of "re-distribution of wealth" to the benefit of the working

people. As can be concluded from Figure 3, the share of labor (L/Y) rises

again with high rates in the period 1981-85. The combination of a rapidly

increasing K/Y with the likewise increasing labor share (i.e., decreasing

profit share in the net product) results now in a rapidly decreasing profit rate

and an economic crisis that corresponds to the Marxian concept of capital

over-accumulation.

The duration and sharpening of the economic crisis led to a crisis in the

PASOK government's economic policy. A temporary aggravation of the

country's balance of payments in 1985 gave government officials reason to

accept that "healthy" conditions of capitalist production could be restored

only when new investment raised surplus-value with a higher rate than it

increased the capital stock. In order to obtain such a result, either the level

of exploitation (Y/L) or the efficiency of capital (Y/K) had to increase, or

both.

The capitalist way out of the crisis presupposes, therefore, a social and

economic restructuring of class power relations. To some extent, but not

exclusively, that depends on the ability of capital to reorganize the

production unit — the capitalist factory and enterprise. In other words, it

presupposes the devalorization of all inadequately valorized capital, and thus

tremendous economizing in the use of constant capital of the capitalist society

as a whole. This means a restructuring of the whole production system, so

that social-capital once more attains a high level of profitability. In any case,

and from the capitalist point of view, the obstructions in restructuring the

production process, and the decrease of real wages imposed on capital by the

strength of the working class, had to be removed.

95

On abandoning its left Keynesian policy, the socialist government

functioned UN tui "executive" of the laws of capital accumulation, taking the

lead in a new massive offensive of the bourgeoisie against the working class.

For the first time since the fail of the military dictatorship (1974), the

economic policies of all major Greek political parties have converged to a

commonly accepted political line and ideological language: "restructuring of

the production apparatus; development of the entrepreneurial sense of the

economy's social partners, improvement of the country's position in the

world market and benefit from the challenge of the European Single Market"

are some of the common "passwords" that unite all Greek political parties,

including the traditional communist Left.

In the 1986-91 period, and especially after the formation of a new

government of the Right in April 1990, the process of devalorization of

non-profitable capital developed faster than ever and was reinforced by the

devalorization of labor-force, resulting from the government's austere

economic policy. However, the crisis of the Greek economy has not been

overcome. As can be concluded from Figures 6 & 7, the profit rate remains

low as a result of the still decreasing "capital efficiency" (Y/K). The

decreasing labor share (which indicates an increasing rate of exploitation)

cannot restore the high levels of profitability on its own unless it is

"reinforced" by an "economy in the use of constant capital" (see also relation

(3) in Section 1 of this paper). Besides, the labor movement and

consequently the labor share itself cannot be suppressed as much as the

ruling class would like. Although the nominal wage increases during the year

of conservative government (April 1990- April 1991) were lower than the

average inflation rate of that period (decreasing wages in real terms), they

were significantly higher than the nominal wage increases initially "planned"

by the government's economic policy. It is also worth noticing in this

context, that the labor share in the net product (L/Y), decreased in the period

1985-87, only to increase again in the following period 1988-89 (Figure 3).

Closing our analysis of the factors which apparently determine the Greek

economic crisis, we can advance our main conclusion: the profit rate

decreased with high rates in the period 1980-85 under the combined

influences of a falling profit share ([1-L/Y]) and an increasing "capital/output

ratio" (K/Y). In the period 1985-89, the profit rate calculated in volume

remained stagnant at low levels, while the same index calculated in value

continued to decrease. In both cases this was due to the continuing decrease

in "capital efficiency" (Y/K), (i.e., the increasing "capital/output ratio"

K/Y). Therefore, the way out of the crisis seems to depend above all on a

restructuring of the production system which will push the value of (K/Y)

downwards, that is, it will significantly economize on constant capital.

However, Greek capitalism has not yet succeeded in this aim.

96

The result stated above definitively indicates that the crisis has the

character of capital over-accumulation, in the Marxian sense of the term, as

described in Section I of this paper.

III. THE HISTORICAL PHASES OF GREEK

CAPITALISM SINCE I960

After discussing the empirical evidence concerning the crisis of the Greek

economy since the end of the 1970s, we will now attempt to reconstruct the

parameters that influenced economic development in Greece during the whole

period studied, by means of the indices-method. We can distinguish four

periods of capital accumulation in Greece since 1960, defined by the turning

points in the evolution of both the main statistical indices studied and the

country's economic and political conjuncture:

1960-73: The Golden Era of Greek Capitalism.

By the early '60s Greek capitalism had entered a long phase of economic

boom and structural changes defined by the two turning points that we have

identified using the indices of capital accumulation: 1962 and 1973. During

this period, Greek manufacturing developed its ability to mass-produce

consumer products as well as means of production. This wide variety of

industries was essentially based on the home market. They expanded and

flourished, keeping pace with the development of a mass-consumption

economy on the one hand and the establishment and rise of a market of

means of production on the other.

Since the early 1950s, Greek capitalism had achieved a high level of

exploitation of the labor force by means of a combination of the most

"traditional" and "modern" production methods. To be more precise, the

production process was based on production of relative surplus-value, as well

as production of absolute surplus-value. According to our analysis, this was

the real "comparative advantage" of Greek capitalism with respect to other,

more developed capitalist countries. The development of relative

surplus-value production did not break up the traditional forms of

exploitation, at least until 1974, leaving enough space for the predomination

of the absolute surplus-value production, in some sectors.

As can be seen in Figures 3, 4, 6 & 7, the period 1960-73 is characterized

by the combination of an increasing "capital efficiency" (Y/K) and a

decreasing labor share (L/Y). The effect of these two parameters is an

increasing profit rate.

This development can be understood in relation to the status of the labor

market and the class struggle in post-war Greece. The civil war (1944 &

1946-49) resulted in the military and political defeat of the Left and the

formation of a quasi-totalitarian political regime of persecution and terror,

not only against Left activists, but also the labor movement. Trade unionism

..........................

97

waa typically “free”, but in reality it was suppressed with all means by the

state. A process of political democratization, connected with an impressive

political and trade unionist mobilization of the working people, was initiated

in the early 1960s. It was violently curtailed, though, by a military coup d'

etat in April 1967. The military dictatorship then devoted itself mainly to the

suppression of the Left and the labor movement.

1974-79: The First Period of the Crisis

The period 1974-1979 can be regarded as the preliminary phase of the crisis,

with high inflation rates, dramatically decreasing rates of investment (I,

Figure 9) and a rapid fall in the marginal profit rate AR (declining

profitability of new investment). However, one could argue that the dynamic

gained by Greek capitalism during its golden era, which started in the early

1960s, was conserved until the end of the 1970s. The economy maintained

sufficient strength, exports increased faster than ever and increasing real

wages boosted domestic demand. As already mentioned, the Output/Capital

Ratio (Y/K) in volume, was stabilized after a fall in 1974 related to the first

oil shock of the period, because of the high capacity utilization rate. This

development slowed down the decrease in the profit rate, mainly caused

during this period by the substantial increase of the labor share and the

squeeze on the profit share in the net product. Figure 11 presents private

consumption in constant prices, for the period of interest 1960-88. One

notices the increasing private consumption, along with the increasing labor

share in the net product, during this preliminary phase of the crisis.

What has happened since 1974 is that radical change in the political and

social relation of forces has benefitted the working class. This process

became known as a "modernizing" of Greek capitalism on the political, as

well as the economic level. The political organization of the working class,

the emergence of trade unionism and the social agitation of the period

1974-78, forced capitalism to accept several changes in favor of the working

class. This meant a "modernizing" of exploitation, or to be more precise, a

retreat from absolute surplus-value production methods. These changes

practically coincided with the two oil shocks of 1973 and 1979, which made

the developing crisis apparent. The international economic conjuncture and

the ascension, since the 1960s, of Greek capitalism in international markets

allowed the Greek bourgeoisie to cope with the new situation. The most

important outcome is Greece's joining the EEC in 1981.

1980-85: The Aggravation of the Crisis

As we mentioned in the previous section of the paper, the period 1980-85

was the phase of acute capitalist crisis per se. The worldwide recession

during the period 1980-82, which lead to shrinking external demand, caused

a slowing down of exports. The economy stagnated in spite of strong internal

demand since the latter, boosted by increasing real wages, contributed mostly

98

to price increases instead of investment. The unemployment rate increased by

more than 6% in the four-year period 1979-83 (Figure 1). Low capacity

utilization rates significantly contributed to decreasing Output/Capital Ratio

(Y/K) and to a fall in the Profit Rate. As can be concluded from Figure 10,

the Output/Capital Ratio, (i.e., Y/K), falls faster than ratio Y/K', where K'

is the "employed fixed capital stock," (i.e., the fixed capital stock K

multiplied by the rate of capacity utilization). The fall in ratio Y/K' means

that during the period examined, the idle productive capacity constituted one

factor determining the fall in ratio Y/K, but not the only factor.

The first election victory by PASOK in 1981 was followed by substantial

real wage increases, even by means of administrative resolutions — a

development of the welfare state (social security payments, pensions and

health expenditures, which had been introduced in Greece on a rather modest

scale until then). Significant changes in labor legislation also followed,

favoring the working class. By 1985, real wages in manufacturing were 70%

above those in 1974 and 15% above those in 1981. At the same time,

austerity triumphed in other European countries.

To compensate for these changes favoring the working class, the Socialist

Party tried to obtain a consensus on working practices, industrial discipline,

productivity increases and intensification of labor during that period. Social

change was presented as a way out of the crisis in the ideology of the

Socialist Party and of the Greek Left as a whole. In other words, a means

of accelerating "economic development." Put differently, the economic

policy for the years 1981-85 was an application of left-Keynesian economics:

demand boosted by real wage increases was supposed to become the

"locomotive" of the economy, reducing unemployment, stimulating

investment and productivity, and bringing "social peace" to the workplace.

Shutting down "non-economic" plants was postponed by means of credit and

state intervention; money supply was not tight and real interest rates were

negative.

The government was thus expecting the economy to respond to its high

public expenditure policy with faster growth and investment. More

specifically, Greek manufacturing was exposed more than ever to

international competition and faced both a dramatic rise in wages and the

development of the home market for consumer products. Yet it was

expected, by government officials, to respond by investing in new, more

efficient technology, keeping capacity utilization rates high, introducing new

organizational principles and working practices, thus boosting productivity.

By 1985 it became evident that this policy was not a success. Neither the

working class nor the bourgeoisie responded positively. The consensus was

not achieved and workers refused to adopt an "enterprise culture," meaning

the adoption of the very logic of capital valorization. The worker continued

to regard "the social character of his work, its combination with the work of

others for a common goal, as a power that is alien to him" (Marx 1981:

99

178), Employers, on the other hand, reduced net investment. During the period

1981-85 the economy stagnated, inflation was high and the profit rate continued

its fall as a result of the squeeze on the profit share on the one hand, and of the

falling "productivity of capital" (increasing Capital/Output Ratio) on the other.

What the Greek experience proves once more is that a government of the

Left is "condemned" to administer capitalist interests, and sooner or later to

confront the working class, since political and economic power remains in

the hands of capital. Moreover, in periods of economic crisis, the

bourgeoisie cannot "afford" any form of social-democratic economic policy,

and it makes use of all available means in order to overthrow it.

1986-91: Some Recovery of Profits

In October 1985, a few months after the second electoral victory of the

Socialist Party, when it was clear that the capitalist way-out of the crisis was

not provided by Keynesian economic policy, the socialist government finally

proclaimed a restrictive economic policy of austerity. The new economic and

political conjuncture gave rise to a massive workers' movement. This

resulted in the highest number of strikes and "lost working hours" (per year)

in Greece since the 1960s, in the subsequent period 1986-88. Massive

retirements from the Socialist Party of union officials and, members

deepened its rift with the workers' movement. The employers' organizations

acknowledged, for the first time since 1981, that the government's economic

policy was "realistic." By 1987, the Labor Share calculated in volume fell

back to the levels of 1979 (Figure 3).

The victory of the conservative party Nea Dimocratia in the 1990 general

elections gave a new force to the monetarist economic policy which Greek

governments followed during this last period. It not only restricted demand

by cutting up wages, public services and public investment, but it also

accelerated the shutting down of nonprofitable plants; the so-called

"enterprises facing problems." It became clear that the preferable capitalist

way of economizing on constant capital is recession, which allows the

collective capitalist to "get rid of" the economically "ineffective," who

burden the profit rate (the "ineffective" individual capitals and the

"ineffective" individuals being the aged, young, women, lower-unskilled

strata of the working class, etc.).

The new conjuncture since October 1985 has not lead to a way out of the

crisis, since it did not mark a reversal in the falling trend of "capital

efficiency" (Y/K). It marked a new phase of the crisis of Greek capitalism,

though, which is characterized by:

(i) The decrease of the Share of Labor (L/Y) in the Net Output, (ii) The

gradual modification of the relations of power in the factory in favor of

capital (stabilization of the labor discipline, acceleration of the

100

filial loakimoglnu

Mm Mill"-.

restructuring process of Greek industry — a process that pushes the

unemployment rate upwards etc.)*

(iii) The changes described above contributed to a significant increase in

the Marginal Rate of Profit (AR). The increase (since 1985, Figure 8)

of the Marginal Rate of Profit (AR) reflects a rise in the profitability

of new investment. Indeed, the Net Fixed Capital Formation (I) has

started to increase since 1986 (for the first time after 1979, Figure 9),

while the net imports of entrepreneurial capital in the Greek economy,

which were dramatically decreasing since 1980, attained an annual

increase rate of 30.2% in 1987, 52.3% in 1988, 6.7% in 1989 and

41 % in 1990, thus reaching the 1979 level in 1988 (calculated in U.S.

dollars and at constant 1980 prices).

(iv) The marginal output/capital ratio (AY/I) in Greek manufacturing has

shown a trend of stabilization since 1985, contrary to the

corresponding average output/capital ratio (Y/K) (see Figure 5). It is

clear then, that if the marginal ratio attains an increasing tendency for

some time and continues to attain higher values than Y/K, this may

result in an increasing trend also of the average output/capital ratio

(Y/K). This is, as argued above, the main factor affecting the profit

rate. However, this development has not yet been apparent.

In the social and economic conjuncture determined by the above described

parameters, the Greek labor movement has become the major — if not the

only — force of opposition in the strategy of the leading capitalist forces and

the government's economic policy which arises from it. The political parties

of the Left can hardly follow the spontaneous initiatives of the working

people (strikes, demonstrations, but also alternative economic policy

propositions stated by trade-union leaders). On the one hand, the Socialist

Party (PASOK) gives some "rear-guard fights" by criticizing the "unsocial"

character of the government's monetarism. On the other hand, the

communist Left, having supported a "mandatory government" of the Right

in the Summer of 1989 {which was supposed to investigate the "economic

scandals" of the previous PASOK government and which practically opened

up the way for the electoral victory of the Right in April 1990), was split up

into two groups in 1991 and is rapidly loosing its political influence on the

working class, which benefits the Socialist Party.

A CONCLUDING REMARK

In our opinion, the Greek capitalism crisis has the character of capital overaccumulation. This hypothesis is supported by our theoretical

presentation of the Marxian capital over-accumulation concept as well as the

empirical analysis of the economic crisis in Greece. The two factors which

determine the character of capital over-accumulation are the decreasing

ability of the capitalist class to economize on constant capital and the

101

decreasing exploitation rate of the labor force from 1975 until 1985. The

second factor has been reversed since 1986 by means of a restrictive

economic policy. However, the increasing exploitation rate since then cannot

compensate for the effect of the decreasing economy in the use of constant

capital (regarding the profit rate) which is proved to constitute the main

parameter determining economic crisis. Furthermore, our analysis has shown

that this decreasing economy in constant capital usage is not the result of any

"technical inadequacies" of the "production system," as the bourgeoisie

economists claim. It is the outcome of the social relation of forces

established in the class-struggle.

NOTES

1. An analytical description of the indices used can also be found in: a) Schoeller Wolfgang,

Weltmarkt und Reproduktion des Kapitals, EVA, Frankfurt/M 1976, pp. 102-107. b) Busch Klaus,

Die Krise der Europaeischen Gemeinschaft, EVA, Frankfurt/M. 1978, pp. 87-214. c) Milios Jean,

Kapitalistische Entwicklung, Nationalstaat und Imperialismus. Der Fall Griechenland, Kritiki

Verlag, Athens 1988, pp. 221-243. d) Barou & Keizer Les grandes economies, Seuil, Paris 1984.

In our calculations of the Labor Share, only the primary distribution of the Value Added is taken into

consideration. The secondary distribution (through taxes, benefits from state education, health etc.)

does not reflect strictly accumulation conditions, but is highly affected by the general relations of

power at the state level, as well as by historical conditions and forms, inherent in each particular

social formation. In order to describe, therefore, the influence upon profitability of changes in the

production process, we preferred to use the profit rate corresponding to primary distribution (that is,

wages and salaries plus compensation of self-employed persons and social insurance paid by

employers).

REFERENCES

Altvater, E., J. Hoffmann, W. Schoeller and W. Semmler. 1974. Entwicklungsphasen und

-tendenzen des Kapitalismus in Westdeutschland. Part A in PROKLA No 13, Berlin, Part B

in PROKLA No 16, Berlin,

Altvater, E., J. Hoffmann and W. Semmler. 1976. Zum Problem der Profitratenberechnung.

in PROKLA No 24, Berlin.

Barou, Y. and B. Keizer. 1984. Les grandes economies. Seuil, Paris.

Billaudot, B. and A. Gauron. 1985. Croissance el crise. La Decouverte, Paris.

Busch, Kl. 1978. Die Krise der Europaeischen Gemeinschaft, EVA Frankfurt, M.

Diefenbach, Ch. G. Groezinger, D. Ibsen, F. Wartenpfuhl and U. Wengenroth. 1976. Wie

real ist die Realanalyse? in PROKLA No 24, Berlin.

Dumenil, Gerard. 1978. Le concept de loi economique dans le Capital, Maspero, Paris.

Epilogi (Monthly Economical Review in Greek language). The Greek Economy in Figures-1990.

1991. (Statistical guide in Greek and English), Electra Press, Athens,.

loakimoglou, E. 1989. Profitability Crisis in Greek Manufacturing, (in Greek). Proc. of the

Second Congress on Greek Industry, organized by the Technical Chamber of Greece, May.

loakimoglou, E. and J. Milios 1986. Crisis and Austerity, (in Greek), Review Thesis. No. 14,

January-March 1986, pp. 7-24, Athens.

loakimoglou, E. and J. Milios. 1988. Automation of Production and Labour Force

Reproduction. Proceedings of Samos Conference on Changing Labour Processes and New

Forms of Urbanization, Thessaloniki.

102

Loiseau, B., J. Mazier and MB Winter. 1977. Rentabilite du capital dans les economies

dominantes. Economic et statistiques No 86.

Marx, Karl. 1981. Capital, Volume 3, Penguin books in association with New Left Review,

London.

Milios, J. 1988. Kapitalistische Entwicklung, Nationalstaat und Imperialismus. Der Fall

Griechenland. Athens: Kritiki Verlag.

Milios, J. 1989. The Problem of Capitalist Development: Theoretical Considerations in View

of the Industrial Countries and the New Industrial Countries. In, Gottdiener, Komninos

(Editors): Capitalist Development and Crisis Theory. Accumulation, Regulation and Spatial

Restructuring, pp 154-173, London-New York: Macmillan Press.

Milios, J. and E. loakimoglou. 1990. Internationalization of Greek capitalism and the balance

of payments, (in Greek). Exandas, Athens.

Schoeller, W. 1976. Weltmarkt und Reproduktion des Kapitals, EVA, Frankfurt, M. p.

102-107.

APPENDIX

Capital

«nil Over-accumulation CrUi·: ...

103

104

Blto loakimoglou «n<i John Milioi

and Over accumulation Criiir. . . .

103

106

rim-, loakimoglnti »n<i i-.i... Milioi

( ,.,.,(,i A. . ..i....i.iii'-ii HIM! < » v « - i in i iniiiilaiM.il Criib: ,,.

107