* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download File

Dharmaśāstra wikipedia , lookup

Brahma Sutras wikipedia , lookup

Vaishnavism wikipedia , lookup

California textbook controversy over Hindu history wikipedia , lookup

Pratyabhijna wikipedia , lookup

Anti-Hindu sentiment wikipedia , lookup

Rajan Zed prayer protest wikipedia , lookup

Buddhism and Hinduism wikipedia , lookup

Indra's Net (book) wikipedia , lookup

Invading the Sacred wikipedia , lookup

Women in Hinduism wikipedia , lookup

Neo-Vedanta wikipedia , lookup

History of Hinduism wikipedia , lookup

Vishishtadvaita wikipedia , lookup

History of Shaktism wikipedia , lookup

Tamil mythology wikipedia , lookup

Hinduism in Indonesia wikipedia , lookup

Hindu–Islamic relations wikipedia , lookup

LGBT themes in Hindu mythology wikipedia , lookup

Karma in Hinduism wikipedia , lookup

Hindu views on evolution wikipedia , lookup

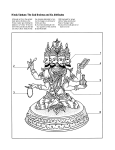

Excerpt from “Hinduism” article on patheos.com/Library, by Jacob N. Kinnard The term "Hinduism" encompasses an incredibly diverse array of beliefs and practices, to the point that Hindus in one part of India might hold particular beliefs and engage in particular practices that would be virtually unrecognizable in another part of India. However, they are unified with basic beliefs and concepts One of the most commonly retold Hindu scriptures is that which describes the creation of the world involving the so-called "Hindu Trinity"—Brahma, Vishnu, and Shiva. There are many variations of this basic scripture. In essence, Vishnu awoke, and said to Brahma that it was time to create the world. Brahma then set about creating the world. He broke a lotus into three pieces, and with the first made the heavens, with the second the skies, and with the third the earth. He then populated the earth with all living beings. Shiva appears later when the world has been engulfed in chaos. He begins to dance, and in the process creates tremendous religious heat that engulfs the world in flames, destroying it but at the same time purifying it (much like what the sacrificial fire does). The cosmos is then once again void, until the waters reappear, and the whole cycle begins again. Just as human beings are born and reborn over and over again, so too is the cosmos. This is samsara. Accordingly, Brahma is often understood to be the creator, Vishnu the preserver, and Shiva the destroyer. This, however, is only part of the story. The Hindu idea of the gods is complex. Though in one sense there is only one god, Brahman, this god is not really a single, manifest entity but the divine principle that animates the entire cosmos. Each of the individual gods, in this sense, is thus a manifestation of Brahman. Vishnu, for instance, takes many, many forms. He also manifests himself in the human realm when dharma has broken down; he sends himself down to earth in the form of an avatara. Krishna is an avatara of Vishnu, as is Rama. But these forms of the gods are not understood to be "lesser" versions of Vishnu. They are each fully and completely Vishnu, as are all of the other manifestations of Vishnu. (pictured: traditional depiction of Krishna) This is related to the concept of Brahman. Brahman is the overarching, all-encompassing divine principle that contains all beings—all of the gods, all humans, all demons, and even all animals. Thus each individual god is at once a particular god with particular characteristics and "personality" traits, and at the same time a complete manifestation of Brahman. Likewise, there are thousands of goddesses in the Hindu pantheon: Lakshmi, Parvati, Saraswati, Kali, Durga, and so on. These goddesses can be quite distinct. Lakshmi, the embodiment of grace and good fortune, is a "cool" goddess, Vishnu's consort, who is motherly and utterly benign. Kali, in contrast, is often a ghastly figure with flaming eyes and a lolling tongue and earrings made of severed heads. Despite their very different personas, however, they are often understood to be different manifestations of Devi, the great goddess who is one. Humans are often only able to see the outward form of the gods and goddesses, because our vision is limited and because we are enmeshed in the illusion that the world we see is the "real" world. This is the effect of maya, illusion. It is maya that makes us think, for instance, that we are individual selves, or atmans. Certainly on one level we exist–we have bodies, we have feelings, thoughts, personalities. But ultimately all of these things are only just illusions. Ultimately, we are all part of Brahman. However, we are ignorant and deluded (by maya), and thus we think we think we are individuals. There are two underlying principles in the Hindu world that are and have been shared by virtually all Hindus: dharma and karma. These principles fundamentally inform Hindu conceptions of moral thought and action. Dharma is one of the most complex and all-encompassing terms in all of Hinduism: it can mean religion, law, duty, order, proper conduct, morality, righteousness, justice, norm. As such, dharma fundamentally underlies conceptions of morality and ethics in Hinduism. Dharma puts things in their proper place, creates and maintains order and balance. To act dharmically is, in essence, to act appropriately; what is appropriate is determined by the context in which the action is to be performed and who is performing it. Different people have different dharmas; one's caste, one's position in life (ashrama), one's gender, all determine what is dharmic in a particular instance. Thus in Hinduism specific ethical and moral guidelines vary; the general ethical and moral principle does not, however. That amounts to a simple moral and ethical imperative: act properly (dharmically). Karma is intimately associated with dharma in this regard. Karma is understood in Hinduism as a universal law of cause and effect. Positive actions produce positive effects; negative actions produce negative effects. When one acts dharmically, one necessarily produces positive karma. This karma is cumulative: one accrues karma, positive and negative, not only throughout the course of one's life, but throughout the course of one's multiple rebirths. It is karma that determines one's rebirths. Karma, negative and positive, keeps us in the world, leading to birth after birth after birth (this is samsara). To attain ultimate salvation, moksha, is to attain release from this cycle. One accomplishes this by eliminating all karma, negative or positive. An extremely important ethical element that pertains to both karma and dharma is the principle of ahimsa, non-violence. This is a very old idea in Hinduism, emerging in its ethical sense in texts as ancient as the Mahabharata, where non-violence is said to generate positive karma. The idea behind ahimsa is that all beings are karmically interconnected; any action that harms another being is said to affect every other being. To kill an animal, then, is to karmically affect not only oneself (and the dead animal, of course), but collectively all other beings. Mahatma Gandhi (pictured) was an advocate of ahimsa, applying it to all aspects of his life, most famously in the political realm. Ahimsa was his fundamental moral and ethical principle, and his teachings on the matter continue to be extremely popular in Hinduism (and outside of the Hindu world as well), regarded as an ideal—if not always an actual—ethical and moral guiding principle.