* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Reactions vs. Reflexes Lab

Survey

Document related concepts

Central pattern generator wikipedia , lookup

Psychophysics wikipedia , lookup

Feature detection (nervous system) wikipedia , lookup

Proprioception wikipedia , lookup

Neuropsychopharmacology wikipedia , lookup

Metastability in the brain wikipedia , lookup

Development of the nervous system wikipedia , lookup

Brain Rules wikipedia , lookup

Neural engineering wikipedia , lookup

Nervous system network models wikipedia , lookup

Stimulus (physiology) wikipedia , lookup

Neuroregeneration wikipedia , lookup

Evoked potential wikipedia , lookup

Transcript

Reactions vs. Reflexes Lab

Background: Have you ever had to react to a situation where something was flying at your

face? If so, you probably used two of our body’s most important – as well as fastest –

mechanisms for protecting your eyes: reflexes and reactions. You automatically closed your

eyes as the object approached and you may have ducked your head out of the way.

Closing your eyes automatically is a reflex. A reflex is an autonomic (or involuntary)

response to a stimulus that helps to protect the body from injury. Reflexes are very rapid

and of short duration since they do not rely upon the brain for “decision making”. This

entire “decision” to react occurs in the spinal cord or brain stem. Other types of reflexes

happen all the time. In fact, your last visit to the doctor probably involved one. When struck

just below the knee with a small hammer, your lower leg “kicks” up to protect the

ligaments inside the knee capsule and to keep your quadriceps from being stretched too

far. If you pick up something very hot, you may drop it to prevent a serious burn. All of

these are examples of reflexes. Ducking your head out of the way is a reaction. A reaction is

a somatic (voluntary) response to a stimulus. This decision involves the brain and requires

the brain to make a decision about what your response will be. A reaction is the deliberate

or voluntary changing of the body’s position to respond to the stimulus. Reactions may also

be very quick and of short duration, but they aren’t always.

Purpose: the purpose of this laboratory experience is:

• to understand the difference between a reflex and a reaction

• to demonstrate some human reflexes

• to be able to calculate your reaction time

Procedure:

Patellar or Knee Jerk Reflex

1. The subject is to sit on the edge of the lab table with the legs able to swing freely.

(One partner will be the subject first and the other partner the tester, then you’ll

switch.)

2. Once the legs are relaxed and swing freely, the tester should use the side of their

hand to “tap” the subject just below the kneecap. What happened? Record your

results in the data table.

3. Now have the person sit with their leg straight out. Tap the knee in the same place.

Observe and record your results.

4. Switch places with your partner and repeat steps 1‐3. Record the data for both

partners in your data table.

Papillary Reflex

5. Have the subject close his or her eyes for one minute (no peeking). After one minute,

stare into the subject’s eyes and tell him/her to open his/her eyes. Observe and

record what happens to the pupils.

6. After the subject has been tested switch places and repeat with the partner.

Babinski’s Response

7. Have the subject remove one shoe and sock. Have the subject sit on the lab table

with his/her foot extending just over the edge. Using a pen cap or fingernail, the

experimenter is to scratch the subject’s foot in one smooth stroke motion from toe

to heel.

8. Describe the response in the toes in your data table.

9. After the subject has been tested switch places and repeat with the partner.

Blink Reflex

10. Have the subject hold a sheet of clear plastic (transparency) in front of their face.

Crumple up a small piece of paper and toss it toward their eyes. Observe what

happens and record your data.

11. After the subject has been tested switch places and repeat with the partner.

Procedure for Reaction Time:

1. Have the subject sit comfortably with their forearm resting on a desk. With their

index finger and thumb about two inches apart. Hold a ruler at the 30 cm end and

have the “zero” (0 cm) mark lined up between your partner’s finger and thumb.

2. Without warning, release the ruler and have them grasp it as quickly as they can.

Record the distance the meter stick traveled to where the thumb meets the stick.

Repeat the trial three more times and record your data.

3. Switch roles and repeat steps 1 and 2.

4. Determine the average distance that the meter stick fell for all of the trials. Using

that average, calculate the TIME it took for you to react and grab the ruler using the

equation on the next page.

Conclusion:

1. In the space below calculate your reaction time and your partner’s reaction time.

Show your work for each.

a. Mine:

b. Partner’s:

2. Why doesn’t the patellar reflex happen when your leg is straight?

3. How does the patellar reflex protect us? How does the papillary response prevent

injury? What would happen without it?

4. Why is the blinking response effective? What kind of job would you have where you

used this reflex quite often?

5. What kind of job would you have where you would want to stop the blinking

response?

6. Name three sports or occupations where having a fast reaction time is important.

7. Give three examples of things that could slow down your reaction time or reflexes.

8. Say that a person catches a meter stick very slowly when their hands are cold. If that

person was able to average catching the meter stick at 93 cm, what is their reaction

time? Show your work below.

APPENDIX #1

SECTION 1: REFLEXES AND REFLEX ARCS

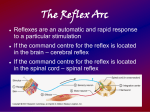

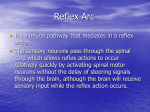

Nerve impulses follow routes through the nervous system called nerve pathways. Some of

the simplest nerve pathways consist of little more than two neurons that communicate

across a single synapse. Reflexes are rapid, involuntary responses to stimuli, which are

mediated over simple nerve pathways called reflex arcs. Involuntary reflexes are very fast,

traveling in milliseconds. The fastest impulses can reach 320 miles per hour.

Reflex arcs have five essential components:

1. The receptor at the end of a sensory neuron reacts to a stimulus.

2. The sensory neuron conducts nerve impulses along an afferent pathway towards the

CNS.

3. The integration center consists of one or more synapses in the CNS.

4. A motor neuron conducts a nerve impulse along an efferent pathway from the

integration center to an effector.

5. An effector responds to the efferent impulses by contracting (if the effector is a

muscle fiber) or secreting a product (if the effector is a gland).

Reflexes can be categorized as either autonomic or somatic. Autonomic reflexes are not

subject to conscious control, are mediated by the autonomic division of the nervous system,

and usually involve the activation of smooth muscle, cardiac muscle, and glands. Somatic

reflexes involve stimulation of skeletal muscles by the somatic division of the nervous

system. Most reflexes are polysynaptic (involving more than two neurons) and involve the

activity of interneurons (or association neurons) in the integration center. Some reflexes;

however, are monosynaptic ("one synapse") and only involve two neurons, one sensory

and one motor. Since there is some delay in neural transmission at the synapses, the more

synapses that are encountered in a reflex pathway, the more time that is required to effect

the reflex.

SECTION 2: THE IMPORTANCE OF REFLEX TESTING

Reflex testing is an important diagnostic tool for assessing the condition of the nervous

system. Distorted, exaggerated, or absent reflex responses may indicate degeneration or

pathology of portions of the nervous system, often before other signs are apparent.

If the spinal cord is damaged, then reflex tests can help determine the area of injury. For

example, motor nerves above an injured area may be unaffected, whereas motor nerves at

or below the damaged area may be unable to perform the usual reflex activities.

Closed head injuries, such as bleeding in or around the brain, may be diagnosed by reflex

testing. Remember that the oculomotor nerve stimulates the muscles in and around the

eyes. If pressure increases in the cranium (such as from an increase in blood volume due to

brain bleeding), then the pressure exerted on CN III may cause variations in the eye reflex

responses.

SECTION 3: SPINAL REFLEXES

The spinal cord provides a major pathway for ascending and descending neural tracts. In

addition to this function, the spinal cord functions as the integration center for many

reflexes. These are called spinal reflexes because their arcs pass through the spinal cord.