* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Theory - ocedtheories

Social Bonding and Nurture Kinship wikipedia , lookup

Conservation psychology wikipedia , lookup

Social psychology wikipedia , lookup

Behavioral modernity wikipedia , lookup

Observational methods in psychology wikipedia , lookup

Symbolic behavior wikipedia , lookup

Learning theory (education) wikipedia , lookup

Abnormal psychology wikipedia , lookup

Neuroeconomics wikipedia , lookup

Thin-slicing wikipedia , lookup

Transtheoretical model wikipedia , lookup

Insufficient justification wikipedia , lookup

Classical conditioning wikipedia , lookup

Organizational behavior wikipedia , lookup

Applied behavior analysis wikipedia , lookup

Attribution (psychology) wikipedia , lookup

Sociobiology wikipedia , lookup

Theory of planned behavior wikipedia , lookup

Adherence management coaching wikipedia , lookup

Theory of reasoned action wikipedia , lookup

Descriptive psychology wikipedia , lookup

Psychological behaviorism wikipedia , lookup

Behavior analysis of child development wikipedia , lookup

Verbal Behavior wikipedia , lookup

B. F. Skinner

1

Theory: Operant Conditioning

Theorist: B. F. Skinner

Biography:

Burrhus Frederic Skinner was born March 20, 1904, in the small Pennsylvania town of

Susquehanna. His father was a lawyer, and his mother a strong and intelligent

housewife. His upbringing was old-fashioned and hard-working. Burrhus was an active,

out-going boy who loved the outdoors and building things, and actually enjoyed school.

His life was not without its tragedies, however. In particular, his brother died at the age

of 16 of a cerebral aneurysm. Burrhus received his BA in English from Hamilton

College in upstate New York. He didn’t fit in very well, not enjoying the fraternity

parties or the football games. He wrote for school paper, including articles critical of the

school, the faculty, and even Phi Beta Kappa! To top it off, he was an atheist -- in a

school that required daily chapel attendance. He wanted to be a writer and did try,

sending off poetry and short stories. When he graduated, he built a study in his parents’

attic to concentrate, but it just wasn’t working for him. Ultimately, he resigned himself to

writing newspaper articles on labor problems, and lived for a while in Greenwich Village

in New York City as a “bohemian.” After some traveling, he decided to go back to

school, this time at Harvard. He got his masters in psychology in 1930 and his doctorate

in 1931, and stayed there to do research until 1936. Also in that year, he moved to

Minneapolis to teach at the University of Minnesota. There he met and soon married

Yvonne Blue. They had two daughters, the second of which became famous as the first

B. F. Skinner

1

infant to be raised in one of Skinner’s inventions, the air crib. Although it was nothing

more than a combination crib and playpen with glass sides and air conditioning, it looked

too much like keeping a baby in an aquarium to catch on. In 1945, he became the

chairman of the psychology department at Indiana University. In 1948, he was invited to

come to Harvard, where he remained for the rest of his life. He was a very active man,

doing research and guiding hundreds of doctoral candidates as well as writing many

books. While not successful as a writer of fiction and poetry, he became one of our best

psychology writers, including the book Walden II, which is a fictional account of a

community run by his behaviorist principles. August 18, 1990, B. F. Skinner died of

leukemia after becoming perhaps the most celebrated psychologist since Sigmund Freud

(Boeree, 2006).

Description of Theory:

The theory of B.F. Skinner is based upon the idea that learning is a function of change in overt

behavior. Changes in behavior are the result of an individual's response to events (stimuli) that

occur in the environment. A response produces a consequence such as defining a word, hitting a

ball, or solving a math problem. When a particular Stimulus-Response (S-R) pattern is reinforced

(rewarded), the individual is conditioned to respond. The distinctive characteristic of operant

conditioning relative to previous forms of behaviorism (e.g., Thorndike, Hull) is that the

organism can emit responses instead of only eliciting response due to an external stimulus.

Reinforcement is the key element in Skinner's S-R theory. A reinforcer is anything that

strengthens the desired response. It could be verbal praise, a good grade or a feeling of increased

accomplishment or satisfaction. The theory also covers negative reinforcers -- any stimulus that

B. F. Skinner

1

results in the increased frequency of a response when it is withdrawn (different from adversive

stimuli -- punishment -- which result in reduced responses). A great deal of attention was given

to schedules of reinforcement (e.g. interval versus ratio) and their effects on establishing and

maintaining behavior.

One of the distinctive aspects of Skinner's theory is that it attempted to provide behavioral

explanations for a broad range of cognitive phenomena. For example, Skinner explained drive

(motivation) in terms of deprivation and reinforcement schedules. Skinner (1957) tried to

account for verbal learning and language within the operant conditioning paradigm, although this

effort was strongly rejected by linguists and psycholinguists. Skinner (1971) deals with the issue

of free will and social control.

Application:

Operant conditioning has been widely applied in clinical settings (i.e., behavior modification) as

well as teaching (i.e., classroom management) and instructional development (e.g., programmed

instruction). Parenthetically, it should be noted that Skinner rejected the idea of theories of

learning (see Skinner, 1950).

Example:

By way of example, consider the implications of reinforcement theory as applied to the

development of programmed instruction (Markle, 1969; Skinner, 1968)

1. Practice should take the form of question (stimulus) - answer (response) frames which expose

the student to the subject in gradual steps

2. Require that the learner make a response for every frame and receive immediate feedback

B. F. Skinner

1

3. Try to arrange the difficulty of the questions so the response is always correct and hence a

positive reinforcement

4. Ensure that good performance in the lesson is paired with secondary reinforcers such as verbal

praise, prizes and good grades.

Principles:

1. Behavior that is positively reinforced will reoccur; intermittent reinforcement is particularly

effective

2. Information should be presented in small amounts so that responses can be reinforced

("shaping")

3. Reinforcements will generalize across similar stimuli ("stimulus generalization") producing

secondary conditioning

Skinner is regarded as the father of Operant Conditioning, but his work was based on

Thorndike’s law of effect. Skinner introduced a new term into the Law of Effect Reinforcement. Behavior which is reinforced tends to be repeated (i.e. strengthened); behavior

which is not reinforced tends to die out-or be extinguished (i.e. weakened). Skinner coined the

term operant conditioning; it means roughly changing of behavior by the use of reinforcement

which is given after the desired response. Skinner identified three types of responses or operant

that can follow behavior. Skinner coined the term operant conditioning; it means roughly

changing of behavior by the use of reinforcement which is given after the desired response.

Skinner identified three types of responses or operant that can follow behavior.

• Neutral operants: responses from the environment that neither increase nor decrease the

probability of a behavior being repeated.

B. F. Skinner

1

• Reinforcers: Responses from the environment that increase the probability of a behavior being

repeated. Reinforcers can be either positive or negative.

• Punishers: Response from the environment that decrease the likelihood of a behavior being

repeated. Punishment weakens behavior.

We can all think of examples of how our own behavior has been affected by reinforcers and

punishers. As a child you probably tried out a number of behaviors and learnt from their

consequences. For example, if when you were younger you tried smoking at school, and the

chief consequence was that you got in with the crowd you always wanted to hang out with, you

would have been positively reinforced (i.e. rewarded) and would be likely to repeat the behavior.

If, however, the main consequence was that you were caught, caned, suspended from school and

your parents became involved you would most certainly have been punished, and you would

consequently be much less likely to smoke now.

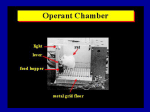

Skinner studied operant conditioning by conducting experiments using animals which he placed

in a “Skinner Box” (see fig 2) which was similar to Thorndike’s puzzle box.

B. F. Skinner

1

Fig 2: A Skinner Box.

Reinforcement (strengthen behavior)

Skinner showed how positive reinforcement worked by placing a hungry rat in his Skinner box.

The box contained a lever in the side and as the rat moved about the box it would accidentally

knock the lever. Immediately it did so a food pellet would drop into a container next to the lever.

The rats quickly learned to go straight to the lever after a few times of being put in the box. The

consequence of receiving food if they pressed the lever ensured that they would repeat the action

again and again.

Positive reinforcement strengthens a behavior by providing a consequence an individual finds

rewarding. For example, if your teacher gives you £5 each time you complete your homework

(i.e. a reward) you are more likely to repeat this behavior in the future, thus strengthening the

behavior of completing your homework.

B. F. Skinner

Theory Measurement/Instrumentation:

1

B. F. Skinner

1

Report Prepared by:

Charles R. Jennings III

References:

Boeree G. C., (2006). B. F. Skinner 1904 – 1990. Retrieved September 13, 2008, from:

http://webspace.ship.edu/cgboer/skinner.html

Markle, S. (1969). Good Frames and Bad (2nd ed.). New York: Wiley.

Skinner, B.F. (1950). Are theories of learning necessary? Psychological Review, 57(4), 193-216.

Skinner, B.F. (1953). Science and Human Behavior. New York: Macmillan.

Skinner, B.F. (1954). The science of learning and the art of teaching. Harvard Educational

Review, 24(2), 86-97.

Skinner, B.F. (1957). Verbal Learning. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Skinner, B.F. (1968). The Technology of Teaching. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Skinner, B.F. (1971). Beyond Freedom and Dignity. New York: Knopf.