* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Internal Assessment Resource

Marriage in ancient Rome wikipedia , lookup

Travel in Classical antiquity wikipedia , lookup

Roman army of the late Republic wikipedia , lookup

Promagistrate wikipedia , lookup

Education in ancient Rome wikipedia , lookup

Food and dining in the Roman Empire wikipedia , lookup

Romanization of Hispania wikipedia , lookup

Roman agriculture wikipedia , lookup

History of the Roman Empire wikipedia , lookup

Slovakia in the Roman era wikipedia , lookup

Switzerland in the Roman era wikipedia , lookup

Roman Republican governors of Gaul wikipedia , lookup

Roman emperor wikipedia , lookup

Alpine regiments of the Roman army wikipedia , lookup

Early Roman army wikipedia , lookup

Roman economy wikipedia , lookup

Culture of ancient Rome wikipedia , lookup

Roman historiography wikipedia , lookup

Constitutional reforms of Augustus wikipedia , lookup

History of the Roman Constitution wikipedia , lookup

History of the Constitution of the Roman Empire wikipedia , lookup

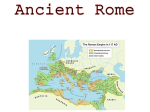

Exemplar for internal assessment resource Latin 3.4B for Achievement Standard 91509 Exemplar for Internal Assessment Resource Latin Level 3 Resource title: Attitude to Rome This exemplar supports assessment against: Achievement Standard 91509 Analyse a Roman viewpoint Student and grade boundary specific exemplar The material has been gathered from student material specific to an A or B assessment resource. Date version published by Ministry of Education © Crown 2012 December 2012 To support internal assessment from 2013 Exemplar for internal assessment resource Latin 3.4B for Achievement Standard 91509 Grade Boundary: Low Excellence 1. To achieve at Excellence the student is required to analyse thoroughly a Roman viewpoint. This involves fully expanding on particular selected points, using Latin references and/or quotations from resources and/or previously studied material to support answers, and drawing perceptive conclusions. An English explanation is provided for any Latin reference or quotation. Latin references may include mention of Roman artefacts, Latin terms, phrases, quotations, images, maps or other material. The student has applied linguistic and socio-cultural knowledge to extract and explore ideas and has expanded fully on the particular selected points (1) supported by Latin quotations with foot-noted translations (3). A perceptive conclusion has been drawn in the body of the work (2) and there is another less strong conclusion in the final paragraph (5). To reach a more secure Excellence the student should explain the allusions (4) and strengthen the conclusion (5). © Crown 2012 Student 1: Low Excellence Latin AS 3.4B Page 1/3 “I found Rome a city of brick and left it a city of marble.i” Augustus Caesar (63BC – 14AD) became the undisputed ruler of Rome when he defeated Marc Antony and Cleopatra at the Battle of Actium. During his long reign he brought about peace and stability in an era known as the Pax Romana (The Roman Peace) and made a concerted effort to redefine the Roman identity. Augustus found his way into the heart of the traditional Roman man through his commitment to restoring Rome to the way in which it had been founded by Romulus and Remus and bringing the Roman government to its rightful power, ruling everything. The Emperor Augustus promoted patriotism during ‘The Golden Age,’ through his encouragement of influential historians and poets to create works in support of his aims and Roman pride. Reflection of such aims is very evident through the analysis of poems such as those of Virgil and Horace and intended effect of what is essentially propaganda is undeniable. (1)An exemplary passage of Virgil’s Aeneid of the ideas of Augustus and how they show national identity and patriotism lie in the passage in which Anchises predicts that Augustus Caesar will go on to make a ‘Golden Age’ once again. ‘hic uir, hic est, tibi quem promitti saepius audis, Augustus Caesar, diui genus, aurea condet saecula qui rursus Latio regnata per arua Saturno quondam.ii’ Augustus in his lifetime went on to exploit his very distant familial connection to Aeneas and the fact that Virgil calls upon Augustus in a prophecy cements his status among the citizens of Rome. Virgil is marking him out for divinity, and the Romans being infatuated with prophecies and gods have no choice but to support this man who was always destined to be their ruler and the purveyor of peace and restoration of ancient culture. The fact that he belongs to the same line of genealogy as Aeneas makes his position as a human of god-like status all the more valid. There is no doubt about the purpose of Augustus in the Roman Empire and Virgil is sharing his view with the Roman population and uniting the people with this sense of national identity as they are all privy to the beliefs under the same ruler. The super natural element of the character of Augustus is only furthered in a following passage where ‘hinc Augustus agens Italos in proelia Caesar cum patribus populoque, penatibus et magnis dis, stans celsa in puppi, geminas cui tempora flammas laeta uomunt patriumque aperitur uertice sidus.iii’ The twin flames are partly associated with his helmet and the twin crests of Romulus, but also give an element of super natural to Augustus himself .There is also an emphasis on the Italians who are now enemies who contributed a great amount to the destiny of Rome. (4)This passage is very interesting in the sense that it makes a lot of historical allusions not only to Romulus but also to Julius Caesar as well. Virgil has succeeding in lifting Augustus’s status only further up the chain of power in awarding him with what is essentially super-human qualities which will go on to bring about the longest periods of peace, stability and prosperity in the history of Rome. The views of the poet unite the views of the people especially as Augustus ‘leads the Italians to conflict, with him the Senate, the people.’ Augustus appears to be fighting for the people with the people and the population of Rome unite under his rule in a single national identity physically expressing their commitment to their nation and its leader in the ultimate act of patriotism just as Augustus has made it so through his careful command over literate promotion.Through his literature Horace supports Augustus. Horace was a contemporary of Julius Caesar and in capturing the very essence of the civil wars: (3)‘sic est: acerba fata Romanos agunt scelusque fraternae necis, ut imerentis fluxit in terram Remi sacer nepotibus cruoriv,’ it becomes very clear that the civil wars are exceptionally dark times in the history of the Roman republic. This is of Latin AS 3.4B Page 2/3 course before the time of Augustus which ultimately leaves him in a powerful position as these murky times in Roman history are accounted. It makes the case for the Pax Romana that Augustus can offer that much stronger. Horace goes on to document the Augustan triumphs at the Battle of Actium: ‘io Triumphe, tu moraris aureos currus et intactas boves?v This passage is monumental as after leaving the Battle of Actium a victor, Augustus essentially became the ruler of what would become the Roman Empire.(1) In this battle Augustus portrays the quintessential traditional Roman man sticking up for traditional Roman beliefs defending the Roman way of life from the inevitable foreign reform of Marc Antony, softened by his partner Cleopatra and how she would have him rule. In fact it seems Marc Antony’s soldiers agree as ‘hostiliumque navium portu latent puppes sinistrorsum citae.vi’ They will not fight for Eastern rule, it seems as if they would have Augustus rule also. This is important for the analysis of the acceptance of the ideals of Augustus by the Romans. How could they not accept somebody who seems to be the embodiment of the traditional Roman man, who is able to have his enemies fleets surrender to him and leave him to be the victor as if it is fated so? Moving to Augustus’s reign (13BC), Horace writes (3)‘dius orte bonis, potume Romulae custos gentis, abes iam nimium Diu; maturum reditum pollicitus partrum sancto consilio redi.vii’ This convincing piece of propaganda subtly promotes Augustus in the eyes of the reader. Horace becomes a voice of the people, the everyday traditional Roman who is concerned for the possibility of another civil war.(1) Horace promotes Augustus to the individual who has taken on the responsibility of maintaining the order and peace of the Roman rule and he reflects his belief in this man urging the everyday Roman man to feel the same way. This shows the national identity of Rome, in the sense that they each belong under the reign of Augustus whether they be a poet like Horace or simply an ordinary man, they all share this feelings and patriotism as they devote themselves completely to their country. A particularly emblematic example of just how highly esteemed Augustus is in the eyes of Horace is evident in an earlier passage of Horace ‘Gentis humanae pater atque custos, orte Saturno, tibi cura magni Caesaris fatis adta: tu secundo Caesare regnesviii.’ It is as if Augustus never existed before he became emperor, this is very indicative of the nature of Augustus and how he has left Octavius behind as if his life before power is irrelevant. Ever the subtle manipulator, it seems as if all of the bad things he has done previously no longer matter as he is now this super-human traditional man. It shows just how clever Augustus was that his rule is being tied with Jupiter’s own rule. Horace is saying that Augustusix is second only to Jupiter and Augustus is transcending ordinary people to this more than human status, up there with the gods that he values so much as per his traditional aims for the people. He is a dictator yet he manages to somehow avoid dictatorship through his restrained promotion with the help of people like Horace. During his reign, Augustus also commissioned Horace to compose a hymn for the long-abandoned festival (17BC) the Carmen Saecularex which Augustus revived in accordance with his policy of recreating ancient customs. ‘Possis nihil urbe Roma visere maius!xi’ This hymn is more than anything a celebration of Augustan rule noting how nothing can ever threaten Rome under Augustus’s leadership. It is a compelling passage as it shows all of the wonderful things the reign of Augustus has bought about. (2) It seems that Horace simply buys into the shameless propaganda because what Augustus can offer the people is attractive even if he is a dictator behind the guise of a man of tradition and dedication to the gods and ancient ways of Rome. This really is the epitome of national identity that something like this would be read at a festival for the crowd to bask in the glory that Latin AS 3.4B Page 3/3 Augustus has bought to the Romans. The patriotism of Horace on behalf of the people makes it clear why Augustus could so easily take and maintain full power of the citizens of Rome. Augustus recreates ancient customs in his strategies surrounding the control of power and the founding of the Roman Empire. With his rise to and constant hold of the power, comes also the founding of a new national identity. Augustus holds views based on the ‘History of Rome’ by Livy and thinks the reason for the downfall of the Republic to be the straying from traditional values and worship of the gods.(5) Augustus aims in his reign to restore such traditions and values and have the population of Rome united under him with a single new national identity, him being their powerful leader that would continue to hold that power. 1 Suetonius Augustus ii ‘This is the man; this is him, whom you so often hear promised you Augustus Caesar, son of the Deified, who will make a Golden Age again in the fields where Saturn once reigned.’ (Virgil: Aeneid VI:791f) iii‘Augustus Caesar stands on his high stern, leading the Italians to conflict, with him the Senate, the people, the household gods, the great gods, his happy brow shoots out twin flames and his father’s star is shown on his head.’ (Virgil: Aeneid VIII. 678f) iv‘That’s so: a bitter destiny dogs the Romans, the guilt of a brother’s murder, since Remus’ innocent blood poured on the ground, a curse on Rome’s posterity’ (Horace: Epodes, VII) v ‘Hail Triumph! Why delay the golden chariots and the unblemished steers?’ (Horace: Epodes IX) vi‘And the opposing fleet, when ordered to larboard, remained there in the harbour.’ (Horace: Epodes IX) vii ‘Son of the blessed gods, and greatest defender of Romulus’ people you’ve been away too long: make that swift return you promised, to the sacred councils of the City Fathers.’ (Horace: Odes IV. 5) viii ‘Father and guardian of the human race, son of Saturn, and the care of mighty Caesar was given you by fate: may you reign forever with Caesar below.’ (Horace: Odes I. 12) ix Note that in this passage Caesar refers to Augustus x The Secular Festival xi ‘You will never know anything mightier than Rome!’ (Horace: Carmen Saeculare) 1 Exemplar for internal assessment resource Latin 3.4B for Achievement Standard 91509 Grade Boundary: High Merit 2. To achieve at Merit the student is required to analyse clearly a Roman viewpoint. This involves expanding on particular selected points unambiguously in English, and drawing reasoned conclusions. The student has used linguistic and cultural knowledge to extract and explore ideas from previously studied material and has expanded fully on particular selected points (1) and supported them with quotations in English (3). Perceptive conclusions have been drawn (2). This work does not reach Excellence because the supporting evidence in Latin does not have an English translation or explanation as required by Explanatory Note 2 of the standard(4). To achieve at Excellence the student needs to explain or translate the Latin quotations (4) and provide the original Latin for the English translations. © Crown 2012 Student 2: High Merit Latin AS 3.4B Page 1/3 (1) One of the core beliefs of the Roman people, one that defined their national identity and coloured the way they viewed the world, was their belief in their ancestry. Romans believed that they were descended from Trojans through the lineage of Rome’s founder, Romulus, whose ancestor Iulus was the son of Aeneas, the famous Trojan Hero. So the Romans believed that they came from the noble and ancient Trojan stock, renowned for their bravery when defending Troy during the 10-year siege by the Greeks and revered throughout the world for the same. This feeling was noted often by Virgil. In The Aeneid he refers to the Roman emperor Augustus as “a Trojan Caesar … Augustus, a Julius, his name descended from the great Iulus” (Book I, lines 286,288.) Virgil also refers to this in the Georgics, when he writes that “our blood’s atoned, long enough, for Laomedon’s perjuries at Troy” ( lines 501-502). Identifying with the Trojans gave the Romans a sense of importance and of being favoured by the gods which strongly shaped their national identity. The Romans believed that the gods favoured them and it was for this reason that they were slowly but steadily conquering the world. The initial reason for supposing divine favour was the ancestry of the Romans. Rome was founded by Romulus, who was fathered by the god Mars. On Romulus’ mother’s side his ancestry could be traced back to Iulus, son of the famous Trojan, Aeneas. Aeneas’ mother was said to be the goddess Venus. Because of the divine ancestry of the city’s founding father Romans felt that these two divinities, Mars and Venus, would be supporting Rome and helping to further her cause. However, the supposed divine favour of Rome wasn’t limited to these two figures – the Romans felt that the whole kingdom of Olympus was supporting them. This is shown in The Aeneid, when Jupiter prophesies about Rome to Venus, telling her of the end of the civil wars (Book I, line 291,(4) “Aspera tum positis mitescent saecula bellis”) and of Augustus (Book I, line 286,288, “Nascetur pulchra Troianus origine Caesar … Iulius”). The fact that the King of the Gods himself made favourable prophesies about the fate of the Roman Empire assures the Romans that all of the gods are on their side. Horace reflects this when, in his Odes, he addresses the god Mercury, [Odes I, lines 45-46, “serus in caelum redeas diuque laetus intersis populo Quirini”]. By referring to the Romans as the “people of Quirinus” Horace shows his belief in the descent of Romans from Romulus (also known as Quirinus) and thus their divine heritage and favour. (1)The Roman’s belief in their destiny to conquer the world was becoming a reality by the first century AD. During his reign Augustus expanded the empire dramatically, his notable conquests being Hispania and expansions into Germania and Africa. Again this is referenced in Book VI of The Aeneid, when Anchises tells Aeneas that Augustus will “extend the empire beyond the Libyans and the Indians” [lines 794-795]. The fruition of this prophecy made the Romans believe more fervently in the other prophecies about the empire and their favoured status in the world. They believed that it was through the god’s favour that they had been so successful in conquests and in the recent civil wars, notably against Mark Antony and Cleopatra when Augustus delivered a crushing defeat at the Battle of Actium; Virgil draws on this belief in The Aeneid, when he writes that “Apollo of Actium sees from above and bends his bow: at this all Egypt, and India, all the Arabs and Sabaeans turn and flee” [Book VIII, line 704-706 ] Latin AS 3.4B Page 2/3 The emperor Augustus played upon the very religious culture of the Romans when crafting his image. Firstly, as the adoptive son of the deified Julius Caesar, from the start he was considered a semi-divine figure as the son of a god – Virgil refers to him as [“Augustus Caesar, divi genus”. The Aeneid, Book VI, line 792,]. Augustus used this as the basis of his image, which was strongly religious. He made himself Pontifex Maximus (Chief Priest) in 13BC and worked hard to portray himself to the masses as a godly and righteous person. This was a difficult task as the bloodshed of the civil wars had tarnished his reputation. However he continued throughout his reign to restore damaged temples and build new temples and other religious structures, most famously the Temple of Caesar, the Temple of Mars Ultor (part of the Augustan forum) and the Ara Pacis (Altar of Peace). The Ara Pacis goes even further as it is lavishly decorated with Roman scenes, including showing the Emperor and his family in sacrificing to the gods. Horace too writes in his Odes of how Augustus had ascended to divinity in the eyes of the common man. The idea that a god was directly ruling them was hugely popular with the intensely religious Romans. After 100 years of brutal civil war it was very comforting for them to think that the gods cared about them enough to send one of their own to govern them, protect them and bring them peace and prosperity. Many Romans believed that Augustus was predestined to bring peace to the world. This belief was reinforced after his triumph against Mark Antony and Cleopatra at the Battle of Actium in 31 BC, which brought an end to a century of civil wars. Virgil uses the idea of the Battle of Actium (and Augustus’ role in it) being predestined in Book VIII of The Aeneid, when the battle is described in a scene on Aeneas’ shield. Virgil writes that “Augustus Caesar stands on the high stern, leading the Italians to the conflict” [Lines 678-679] and late writes of the Roman triumph as “all Egypt, and India, all the Arabs and Sabaeans turn and flee” [Lines 705-706]. The fact that this great event was depicted on the shield forged by the god Vulcan for the great Trojan hero Aeneas, the ancestor of the Romans, reinforced the Roman’s belief that Augustus’ victories in the civil wars and his end to the wars were destiny. Of course, Augustus’ destiny to bring lasting peace to the Roman Empire was also foretold in Book VI of The Aeneid, in the famous lines (3)“This is the man, this is him, whom you so often hear promised you, Augustus Caesar, son of the Deified, who will make a Golden Age again in the fields where Saturn once reigned” [Lines 791-794 ]. Augustus used the idea of his predestination to bring peace as propaganda, and built his monument, the Ara Pacis Augustae (Altar of Augustan Peace), a great monument to the peace and prosperity that the Romans were enjoying under his rule, reinforcing, in the scenes portrayed on the altar and even in the name itself, that the peace of the Romans was due to his leadership – the Pax Romana was remodelled into the Pax Augusta. (2)The Roman national identity was founded on the idea of their descent from the famous Trojans and their divine heritage. They believed that Rome was favoured by the gods for peace and prosperity, and that it was the destiny of the Roman people to conquer the world and bring order and peace to the “barbarians” who lived outside their empire. When Augustus became emperor he drew upon these beliefs and integrated himself into them in order to put the stain of the civil war behind him. He created an image for himself as a pious, religious ruler, which pleased the intensely religious Roman masses. Drawing upon his link to the deified Julius Caesar, his adoptive father, he Latin AS 3.4B Page 3/3 made himself into a divine figure, which was again popular with the Romans: they were comforted to think that they were so favoured by the gods that one would deign to descend to earth and rule over them. With the aid of works such as Virgil’s Aeneid Augustus even persuaded the masses that he was destined to rule them and to return them the mythical, utopian Saturnian age, when the world would be at peace and Rome would prosper, an age known as the Pax Augusta, or Age of Augustan Peace. (2) Augustus’ image as protector of Roman religion, divine being and the saviour destined to put an end to the misery and bloodshed of 100 years of civil wars in order to usher in a golden age was a massive part of the Roman’s collective psyche and shaped their national identity during his reign and even after his death, making Augustus one of the most successful propagandists of all time and arguably the most influential person the Roman world ever saw. Latin AS 3.4B Page 1/2 Exemplar for internal assessment resource Latin 3.4B for Achievement Standard 91509 Grade Boundary: Low Merit 3. To achieve at Merit the student is required to analyse clearly a Roman viewpoint. This involves expanding on particular selected points unambiguously in English, and drawing reasoned conclusions. The student has applied linguistic and socio-cultural knowledge to extract and explore ideas from previously studied written material and has expanded on particular selected points (1). Reasoned conclusions have been drawn (2). The student has supported the points made with quotations from Latin (3). To achieve a more secure Merit the student should expand more on the idea of peace or tradition. © Crown 2012 Student 3: Low Merit Emperor Augustus (63BC – 14AD) was the founder of the Roman Empire and its first emperor, ruling from 27 BC until his death in 14AD. He initiated an era of peace known as the ‘Pax Romana’ or the Roman peace. Despite some wars, the Mediterranean world remained at relative peace for over two centuries. Before this, Rome lay in an area rifled in civil wars, and the Romans were ready for this era of peace by the time the emperor Augustus came around. Augustus used this idea to propel himself into the Roman’s hearts. They were fed up with civil wars, ready for peace, and Augustus was keen to restore Rome in the same way it had been founded by Romulus and Remus, and Aeneas, and put it back in its place, which was where they believed, on top of the world. We can see both the Roman’s attitude to Augustus and elements of his leadership reflected in Latin literature, such as Virgil’s ‘Aeneid’ and Horace’s Odes. (1)One of the most important aspects of the Roman society was that they were infatuated and even obsessed with tradition and the gods. They were proud of their city, but in a more arrogant sense and believed that the gods favoured them due to their civilisation which was developed beyond their time and also the systems which operated within this. They had a strong faith in the gods and all prophecies and future-tellings. ‘hic uir, hic est, tibi quem promitti saepius audis, Augustus Caesar, diui genus, aurea condet saecula qui rursus regnata per arua Saturno quondam.’1 What is important to note in this prophecy given by Anchises (1) is the reference to the fact that Augustus would one day make the Golden age, and that he is the son of the ‘deified’ Julius Caesar. The Romans valued the deity very highly, and by linking Augustus to images of Godliness and glory shows just how much faith and trust the Romans would have been prepared put in him at the time. Their national identity was on the line, and the first emperor Augustus stepped up to the plate by assuring them an era of peace in Rome, focused on reforming the city to even greater glory. This propaganda played exactly to the Roman’s general and slightly arrogant desire to be the best city and civilisation in the world, and more importantly the most favoured by the Gods. ‘hinc Augustus agens Italos in proelia Caesar cum patribus populoque, penatibus et magnis dis, stans celsa in puppi, geminas cui tempora flammas laeta uomun patriumque aperitur uertice sidus.’2 Similarly in this section, Virgil has placed emphasis on the family line between Caesar and Augustus. He also emphasises again the importance of all kinds of gods to the Roman people, and their firm belief in them, even in the matters of keeping them safe in war. The reference to the twin flames relates to the twins Romulus and Remus, two of the most important figures in Roman history as they were the initial founders of Rome. Augustus is also given a supernatural reference to the stars and the fact that his father (a blood link to the deity) was made a god (or star in this case) when he died. (2)These were all very important aspects of Augustus to the Romans because we know that they placed their belief firmly in their tradition and the Gods and the way Virgil has link Augustus to these in his writing shows us how influenced the Romans were to be able put their faith in him as their ruler. 1 This is the man, this is him, whom you so often hear promised you, Augustus Caesar, son of the deified, who will make a Golden age again in the fields where Saturn once reigned..’ Virgil, Aeneid VI 791f 2 On one side Augustus Caesar stands on the high stern, leading the Italians to the conflict, with him the Senate, the People, the household gods, the great gods, his happy brow shoots out twin flames, and his father’s star is shown on his head. Virgil Aeneid VIII 678f Latin AS 3.4B Page 2/2 Horace wrote about Augustus in a very different way to that of Virgil. Horace, like most of the Romans, hated the times of civil wars and feared what would happen if Augustus were to die, believing Rome would fall back into chaos and treachery of war. He supports Augustus fully for this reason, enjoying the era of peace and this view is not only his own but actually the same as many of the Roman people. ‘Dius orte bonis, optume Romulae custos gentis, abes iam nimium diu; maturum reditum pollicitus partum sancto consilio redi.’3 Horace wrote this in a time where Augustus had been away and obviously he had been worrying about what would happen to him if Augustus were to disappear and the Empire was to collapse. Horace is sucking up to Augustus here out of fear. This feeling represents probablt what a lot of the Roman population felt, supporting him out of fear as they were so keen to see he end of the civil wars.(1) The idea of an era of peace was so inviting that Augustus gained a lot of the support he required to run a successful empire. Again in this passage, like in Virgil’s, a reference has been made to his family ties with Caesar and the Gods, and also to Romulus himself. These references made would affirm the Romans belief in him when they read the piece because of their everlasting values in their history, tradition, and the deity. The Carmen Saeculare is a hymn written by Horace which was commissioned by Augustus himself in 17BC. The poem is in the form of a prayer to Apollo and Diana and represents a return to the tradition of glorifying the Roman Pantheon. It also brings prominence to the patron god of Augustus, Apollo. (3)‘di, probos mores docili iuventae, di, senectuti placidae quietem, Romulae gentui date remque prolemque et decus omne.’4 The prayer asks the Gods for the restoration and glorification of Rome, and make it as mighty as they believe it should be. Again here we see Augustus linked to ideas of the deity and their city of Rome. It can also be noted that Horace wrote this poem for Augustus himself, reinforcing his ‘sucky up’ attitude towards him. These pieces of poetry reflect not only the attitude of the poets towards the emperor of Augustus but also the citizens themselves. (2)The start of the Roman Empire saw the start of an era of relative peace, which they had Augustus to thank for. Everyone was prepared to support him due to this phase of peace. We can see how Horace was so worried about the civil wars restarting that he wrote continuously about Augustus, praising his leadership and him as a person too. (2)Virgil writes similarly, emphasising on his links to his father, Julius Caesar, and stressing the fact that he was a half God so therefore Augustus had a link to the Deity, which we know was very important to the Roman people. The poets give him supernatural characteristics, and make him appear as a great hero in their texts. The Golden age, in the scheme of the history of Rome, was an even further development of their civilisation, which was already beyond its time. A welcome era of peace enforced by Augustus saw the people go back and restore their city, further enforcing their love and dedication to the gods on the way and also reminding each other of the importance of their history regarding Romulus and Remus, and the traditions they have always followed. 3 Son of the blessed Gods, and greatest defender of Romulus’ people, you’ve been away too long: make that swift return you promised, to the sacred councils of the City Fathers.’ Horace, Odes IV lines 1-5 4 Then, you divinities, show our receptive youth virtue, grant peace and quiet to the old, and give children and wealth to the people of Romulus and every glory. Horace, Carmen Saeculare. Exemplar for internal assessment resource Latin 3.4B for Achievement Standard 91509 Grade Boundary: High Achieved 4. To achieve the student is required to analyse a Roman viewpoint. This involves applying linguistic and cultural knowledge to extract and explore ideas from previously studied written/visual material, and to draw conclusions about the viewpoint. The student has applied linguistic and cultural knowledge to extract and explore ideas from previously studied writings of Virgil and Horace (1). Conclusions have been drawn from the material explored (2). To achieve at Merit the student should expand more on ideas such as (3) Augustus’ link with Julius Caesar and the importance of the Carmen Saeculare as well as strengthening the conclusions. © Crown 2012 Student 4: High Achieved Latin 3.4B Page 1/2 Emperor Augustus (63BC – 14AD) was the founder of the Roman Empire and its first emperor, ruling from 27 BC until his death in 14AD. He initiated an era of peace known as the ‘Pax Romana’ or the Roman peace. Despite some wars, the Mediterranean world remained at relative peace for over two centuries. Before this, Rome was plagued by civil wars, and the Romans were ready for this era of peace by the time of Augustus. Augustus used this idea to win the Roman’s support. They had had enough of civil wars and were ready for peace, and Augustus was keen to restore Rome to the way it had been founded by Romulus and Remus, and gain world supremacy. We can see the Roman’s attitude to Augustus and elements of his leadership reflected in Latin literature, such as Virgil’s ‘Aeneid’ and Horace’s Odes. One of the most important aspects of the Roman society was that they loved tradition and the gods. They were proud of their city and what it had become and believed that the gods favoured them and also the systems which operated within this. (1)They had a strong faith in the gods and all prophecies and future-tellings. e.g. “This is the man, this is him whom you so often hear promised you, Augustus Caesar, son of the deified, who will make a Golden Age again in the fields where Saturn once reigned…” Virgil, Aeneid vi 791 f. What is important to note in this prophecy given by Anchises is the reference to the fact that Augustus would one day make the Golden age, and that he is the son of the ‘deified’ Julius Caesar. The Romans valued religion very highly, and by promising peace Augustus was winning them over. Their national identity was at stake and Augustus assured them of an era of peace in Rome, focused on reforming the city to even greater glory, its former glory. This propaganda played exactly to the Roman’s desire to be the best in the world, and more importantly the most favoured by the Gods. “On one side Augustus Caesar stands on the high stern, leading the Italians into conflict with him the Senate, the People, the household gods, the great gods, his happy brow shoots out twin flames, and his father’s star is shown on his head.” Virgil Aeneid viii 678f. (3) In this section, Virgil has placed emphasis on the family line between Caesar and Augustus. He also emphasises again the importance of all kinds of gods to the Roman people, and their firm belief in them, even in the matters of keeping them safe in war. The reference to the twin flames relates to the twins Romulus and Remus, the initial founders of Rome. Augustus is also given a supernatural reference to the stars. These were all very important aspects of Augustus to the Romans because we know that they placed their belief firmly in their tradition and the gods and the way Virgil has linked Augustus to these in his writing shows us how influenced the Romans were to put their faith in him as their ruler. Horace, like most of the Romans, hated the times of civil wars especially since he had been involved in them and feared what would happen if Augustus were to die, believing Rome would fall back into chaos and treachery of war. (1) He supports Augustus, enjoying the era of peace and this view is what many Romans shared. dius orte bonis, optume Romulae custos gentis, abes iam nimium diu; maturum reditum pollicitus partum sancto consilio redi.Odes iv lines 1-5. Horace wrote this in a time where Augustus had been away and obviously he had been worrying about what would happen if Latin 3.4B Student 4 Page 2/2 Augustus were to disappear and the Empire was to collapse. Horace is flattering Augustus out of fear. This is probably what a lot of the Roman population felt, supporting him out of fear as they were so keen to see the end of the civil wars. The idea of an era of peace was so inviting that Augustus gained a lot of the support he required to run a successful empire. Again in this passage, like in Virgil’s, a reference has been made to his family ties, and also to Romulus himself. (2) These references made would affirm the Romans’ belief in him when they read the piece because of their everlasting values in their history, tradition, and the deity. (1) The Carmen Saeculare is a hymn written by Horace which was commissioned by Augustus himself in 17BC. The poem is in the form of a prayer to Apollo and Diana and represents a return to the tradition of glorifying the Roman Pantheon. It also brings prominence to the patron god of Augustus, Apollo. The prayer asks the Gods for the restoration and glorification of Rome, and make it as mighty as they believe it should be. “Then you divinities, show our receptive youth virtue, grant peace and quiet to the old, and give children and wealth to the people of Romulus and every glory” Horace Carmen Saeculare. These pieces of poetry reflect not only the attitude of the poets towards the emperor of Augustus but also the citizens themselves. (2)The start of the Roman Empire saw the start of an era of relative peace, which they had Augustus to thank for. Everyone was prepared to support him due to this phase of peace. The poets give him supernatural characteristics, and make him appear as a great hero. A welcome era of peace enforced by Augustus saw the people go back and restore their city, further enforcing their love and dedication to the gods on the way and also reminding each other of the importance of their history regarding Romulus and Remus, and the traditions they have always followed. Exemplar for internal assessment resource Latin 3.4B for Achievement Standard 91509 Grade Boundary: Low Achieved 5. To achieve the student is required to analyse a Roman viewpoint. This involves applying linguistic and cultural knowledge to extract and explore ideas from previously studied written/visual material, and to draw conclusions about the viewpoint. The student has applied linguistic and cultural knowledge to extract and explore the idea of national identity from previously studied writings of Virgil and Horace (1) and of patriotism under Augustus from the artefact the Ara Pacis (2). The conclusions (3) are not strong. To reach a more secure Achievement the student could expand on the point about Rome’s divine ancestry (4) with more references to Latin sources. The link between Augustus, patriotism and propaganda should be more clearly explained with reference to the Ara Pacis. The conclusions should be clearly drawn from the evidence presented. © Crown 2012 Student 5: Low Achieved AS 3.4B Page 1/2 “I found Rome of clay, I leave it to you of marble.” Throughout the Golden Age of 1st century BCE Rome, Emperor Augustus favoured the Romans’ strong sense of national identity. From the original founding of Rome, tradition was highly valued as a means of creating societal continuity from their ancient past and historical present. The legend of Romulus and Remus remained pivotal to the Romans’ conveyance of national pride. Further, the ensuing curse and civil war that was devastating Rome as a consequence of Romulus and Remus’s bloody battle found solace and cessation during the Augustan Golden Age. The Romans were a proud people and it is clear through their insatiable obsession with their background and its links to the gods that such a tradition was unequivocally important to all of their society. The Golden Age of Augustus provides a modern audience with unambiguous examples of the Roman’s national identity and patriotism in 1st century BCE Rome. The legendary founding of Rome in 753 BCE has a stronghold on the national pride of the Romans. As the myth goes, twin brothers Romulus and Remus- having been suckled by wolves and raised by a shepherd after being thrown from their kingdom as babies-fought to the death on the Palatine hill regarding who would give their name to the new city. This is significant as it is commonly understood that Romulus and Remus are of divine ancestry: their mother Rhea Silvia although a Vestal Virgin was impregnated by either the god Mars or the demigod Hercules and it is accepted that they are descendants of Aeneas’s, the original founder of the Western Land in Italy. Having the founders of their city so strongly connected to divine roots play a vital roole in the perpetuation of the Romans’ passion for religion. (1) Further than this, as mother of Aeneas as told by Virgil in The Aeneid, Venus is commonly associated as the mother of the Roman people. Religion is a powerful tool as a means of control and it is apparent that even as early as 1st century BCE it was being utilised as a way to organize the Roman society- and the Romans not only endured the important role of the gods in their daily life but revered it. How is it that a single man, Augustus, came to lead the entire Roman Empire?(4) The opening lines of Horace’s Odes IV.5 read in favour of Augustus’s divine ancestors, saying (1)“divis orte bonis, optume Romulae custos gentis...” which in English holds the meaning “Son of the blessed gods, and greatest defender of Romulus’ people...” (3)This is an example of the Romans’ sense of national identity in relation to Augustus’s skill as a leader as well as their legendary founding. Arguably the most celebrated effect of Augustus’s reign in 1st century Rome was his leadership that led the Romans from a seemingly endless period of civil war to an era of peace. This is apparent to a modern audience through such monuments as the Ara Pacis in Rome. (2) It is a fine example of not only Roman loyalty but also Augustan propaganda. The Ara Pacis was built to commemorate the winning of two battles at Gaul and Hispania under the command of Augustus. Before Emperor Augustus came to power, civil war was rife in the Roman state. In Horace’s Odes 1.2 the final stanza reads “hic magnos potius triumphus, hic ames dici pater atque princeps, neu sinas Medos equitare inultos t educe, Caesar”; which can be translated as “Here to delight in triumphs, in being called our prince and father, making sure the Medes are punished, lead us, O Caesar.” This quote from a contemporary author of 1st century BCE Rome highlights societal views regarding their appreciation of Augustus’s leadership and his ability to triumph. Patriotism was an important part of Roman society and patriotism in the Roman Empire was fundamentally linked to propaganda. The Ara Pacis, translated as the Altar of Peace was originally named Ara Pacis Augustae which means the Altar of Page 2/2 Augustan Peace. Such propagandistic materials as this were useful to Augustus as a means to leading an empire that was basically ruling the Western world. Literary evidence of Augustus’s affect on the nationalistic values of the Romans are commonly found in epic poet Virgil’s The Aeneid. Virgil frequently makes reference to the strength of Augustus’s leadership with such quotes as “aspera tum positis mitescent seacula bellis” meaning “then with wars abandoned, the harsh will grow mild” (Virigil Aeneid 1). As was well established throughout my essay, Rome maintained a strong sense of national identity and patriotism throughout the 1st century BCE. Augustus not only nurtured by utilised this favour held by the Roman citizens to bring the Roman Empire into power throughout the known Western lands. (3) Augustus won important battles, brought peace to a land known for its skill at warfare and led the society whilst stressing the importance of religion. Thus, the Roman Empire survived under the rule of Augustus with a sense of great national pride, identity and patriotism. Exemplar for internal assessment resource Latin 3.4B for Achievement Standard 91509 Grade Boundary: High Not Achieved 6. To achieve the student is required to analyse a Roman viewpoint. This involves applying linguistic and cultural knowledge to extract and explore ideas from previously studied written/visual material, and to draw conclusions about the viewpoint. The student has applied linguistic and socio-cultural knowledge to extract ideas from previously studied material (1) but has not really explored them nor drawn conclusions. To reach Achievement the student should explore all the ideas extracted. For example the student could explain why Augustus manipulated the Roman people’s ideas in a quasi-religious vein (2). The student should also draw conclusions based on the ideas explored. © Crown 2012 Student 6: High Not Achieved Latin3.4B Page 1/1 Virgil’s masterwork, The Aeneid, included many prophecies of the time of Augustus, the Golden Age and the Pax Romana (Peace of Rome). After 100 years of civil war the Romans were desperate for an end to the bloodshed and a return to peaceful society. In The Aeneid Book VI the hero Aeneas enters the Underworld and meets his father, Anchises, who shows him those who will be his descendants, (1)including the emperor Augustus, “who will make a Golden Age again in the fields where Saturn once reigned” [lines 792-794, “aurea condet saecula qui rursus Latio regnata per arua Saturno quondam”]. The Pax Romana – or, as it came to be known, Pax Augusta – is prophesied in The Aeneid by Jupiter, the King of the Gods, to his daughter Venus. He tells her that “with wars abandoned, the harsh ages will grow mild” [Book I, line 291, “Aspera tum positis mitescent saecula bellis”]. (1)Augustus built heavily on the image of himself as the ultimate religious ruler in making himself divine. This is reflected in the title of his autobiography of sorts, the Res Gestae Divi Augusti: this translates as “The Deeds of the Divine Augustus”. Virgil heavily references Augustus’ supposed divinity in his works, referring to him in The Aeneid as “Augustus Caesar, son of the Deified” [Book VI, line 792, “Augustus Caesar, divi genus”] and in the Georgics as “Caesar, who, in time, will live among a company of the gods” [Georgics I, lines 24-25, “tuque adeo, quem mox quae sint habitura deorum concilia”]. Horace too writes in his Odes of how Augustus had ascended to divinity in the eyes of the common man: “[he] calls on you, as god, at the second course; he worships you with many a prayer, with wine poured out, joins your name to those of his household gods” [Odes IV, lines 32-35, “te mensis adhibet deum; te multa prece, te prosequitur mero defuso pateris et Laribus tuum miscet numen”]. The Ara Pacis Augustae: The Ara Pacis is probably the most famous monument built during Augustus’ reign and it incorporates most of his propaganda through the images carved onto it. While not all Romans could read, all would be able to look at the scenes portrayed on the Ara Pacis and understand both the obvious stories and the subtle subtexts they incorporated. The scene showing Aeneas sacrificing to the Penates saved from Troy links the image of Aeneas to the Forum of Augustus where the Penates were kept. Across many of the scenes on the Ara are oak wreathes and branches, which to the Roman viewers would have symbolised salvation . In the scene portraying the twin babies Romulus and Remus with the she-wolf, the three are watched by Faustulus (the shepherd who rescues them) and the god Mars, their father; both observers seem to be marvelling at this miracle, which came about through providence. And of course, Augustus himself is shown on the Ara, dressed in priestly garments and making a sacrifice to the gods.(2) In these scenes Augustus manipulated the viewer’s thoughts into a quasi-religious vein, and subtextually reminded those who saw the images of many of his propaganda ideas.