* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Verb Extensions in Abo (Bantu, A42)

Ukrainian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Swedish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Germanic strong verb wikipedia , lookup

Portuguese grammar wikipedia , lookup

Ojibwe grammar wikipedia , lookup

Modern Hebrew grammar wikipedia , lookup

Yiddish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Old Norse morphology wikipedia , lookup

Sanskrit grammar wikipedia , lookup

Old English grammar wikipedia , lookup

Serbo-Croatian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Spanish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Navajo grammar wikipedia , lookup

Ancient Greek grammar wikipedia , lookup

Georgian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Scottish Gaelic grammar wikipedia , lookup

Latin syntax wikipedia , lookup

Kannada grammar wikipedia , lookup

Kagoshima verb conjugations wikipedia , lookup

Pipil grammar wikipedia , lookup

Turkish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Sotho parts of speech wikipedia , lookup

Lexical semantics wikipedia , lookup

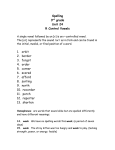

This printout has been approved by me, the author. Any mistakes in this printout will not be fixed by the publisher. Here is my signature and the date ___________________ Verb Extensions in Abo (Bantu, A42) Clare S. Sandy University of California, Berkeley 1. Introduction* This paper describes the derivational verb extensions of Abo, with a particular focus on segmental forms and the historical and comparative implications of the findings. Reflexes of Proto-Bantu extensions in Abo are shown to be very reduced in form and integrated with the root, similar to what is seen in Basaá, a related language. Two extensions that are not clear reflexes of Proto-Bantu extensions are detailed: the passive, which is cognate to the Basaá passive, and the associative which seems not to have a Basaá cognate. Finally, a phenomenon by which multiple semantically empty extensions are stacked up in some verb forms is investigated. The findings in this paper are based upon work with only one speaker, and should therefore be considered preliminary. Additional work with multiple speakers will be required to confirm and clarify the results. In this section, background on the context and phonology of the language is given, followed by a brief overview of the verb extensions in Abo. Section 2. contains a discussion of a vowel raising process common to many of the extensions. In Section 3., each of the extensions are described and exemplified in turn. Combinatorics of the extensions are discussed in Section 4., and conclusions are given in Section 5. 1.1. Language Background Abo [áɓò], also known as Bankon [ɓàŋkón], is classified as a Bantu A42 language (Guthrie 1953), and is part of the Basaa group. It is most closely related to Barombi (Lombi, Rombi). Abo is spoken in the Littoral province of Southwestern Cameroon, in western central Africa. The language has approximately ~12,000 speakers (Lamberty 2002); many also speak Duala (A24). The segment inventory for Abo is given in (1).1 The voiceless velar obstruent alternates predictably with a voiced velar obstruent and a voiced velar fricative in most situations, however, all three sounds are written distinctly here, following the practical orthography and pending additional analysis of their phonemic status. (1) Consonants p t b, ɓ d, l m n mb nd f s w Vowels c [ʧ] j [ʤ] ny [ɲ] nj [nʤ] k g, gh [ɣ] ŋ ŋg, ŋk high mid-close mid-open low front i e ɛ back u o ɔ a y [j] Possible syllables in Abo are CV, CVV, and CVC, where C can be a consonant cluster. Allowable consonant clusters are a stop followed by a glide (CG), a nasal followed by another consonant (NC) or * 1 Acknowledgements: the data in this paper was elicited as part of the 2010-2011 Field Methods class at UC Berkeley, taught by Larry Hyman, and subsequent elicitation sessions stemming from that work. Much of the data and analysis presented in this talk represents a collaborative effort between the author, Florian Lionnet, and Larry Hyman, so I thank them for their data and insights. Many thanks are also due to our Abo consultant, Achille Massoma. Where practical orthography used in this paper differs from IPA in this table, IPA is given in brackets. an by an obstruent plus glide sequence (NCG). Closed syllables are acceptable, including word-finally. Long vowels are only possible in monosyllabic words. Abo has two lexical tones, low (L) and high (H). Downstep creates phonetic mid tones. There are two tone patterns for verbs, H and L, with only a handful of exceptions. Nouns show more tone patterns, including H, L, LH, and HL, as well as a few less common patterns. Various syntactic and morphological processes trigger complex tone changes on words, in particular, much inflection is effected through tone (see Hyman and Lionnet (2011) for more on this topic). 1.2. Overview of Abo Derivational Verb Morphology The verb extensions found for Abo are the applicative, associative, causative, gerundive (aka imperfective), passive, reciprocal, and resultative (aka stative), as shown in the table in (2). Extensions absent from Abo are a reflexive and a reversive. A total of 249 verb roots were checked for productivity with the extensions found. The extensions vary in productivity, and could not combine with all verb roots. The number of verbs each extension was found to combine with is indicated in (2) as a measure of the extension's productivity. (2) Summary of Abo Verb Extensions2 Extension Gloss APPLICATIVE 'X for' ASSOCIATIVE 'X with' CAUSATIVE 'cause to X' GERUNDIVE 'Xing' PASSIVE 'be Xed' RECIPROCAL 'X each other' RESULTATIVE 'is/has Xed' Form ¨ -V -(l)a ¨ -(V)s -ak -(l)abɛ -na ¨ -í/V́ # Verbs 150 212 221 138 152 unknown 200 Example (nám 'hide') némé námá némés námâk námábɛ́ némé The uses of the extensions listed here can overlap, and some have idiosyncratic uses. The primary focus of the current work is on the form of these extensions, so their precise semantic and syntactic functions are not detailed here. We choose to analyze the final vowels in Abo verbs as part of the suffixes they appear with. Because of the acceptability of consonant-final words in the language in general, there is no need to posit a 'final vowel' requirement. Further, because of the tonal expression of inflection, positing final vowels as part of the inflectional system does not seem to be the correct analysis for Abo. 2. Vowel Raising A vowel raising process is triggered by several of the verb extensions, so the basic pattern is described once here, and referred back to, rather than being illustrated separately for each extension. When an extension that triggers vowel raising is added to a stem, low vowels and open mid vowels in the resulting stem are raised (including both the root vowel and any copy vowel, if present). Close mid vowels and high vowels exhibit no change. A schematic diagram of the raising pattern is given in (3). Vowel raising is exemplified in (4) by the effects of the causative extension on verb roots containing various vowels. 2 In this table, a diaeresis in the Form column indicates that the extension is a trigger for vowel raising where applicable, a V in the Form column represents a copy vowel, and the # Verbs column gives the number of verbs found that the extension could combine with. (3) Raising pattern schema: i e ɛ u o ɔ a (4) Basic raising pattern, illustrated with causatives: GLOSS VERB CAUSATIVE a. get stuck tík tíghís b. block kéŋ kéŋés c. refuse, forbid tɛ̀w tèwès d. add ɓát bétés e. wet, be sɔ̀p sòpòs f. cough kós kósós g. undress sùm sùmùs Vowel raising sometimes results in homophony between verb stems, as seen in (5). (5) bwɛ̀ 'catch, seize, arrest' bwè 'have' causative: bwès causative: bwès The raising pattern described above is quite robust, but there are a few exceptions. While most close mid vowels do not raise, a few do, and while most open mid and low vowels do raise, a few do not. In a previous description of Abo by Atindogbé (1996:149), all vowels raise by one step, in contrast to the present findings. It is possible that this discrepancy is due to individual speaker or dialectal differences. 3. Abo Verb Extensions 3.1. Causative Abo has both a direct causative, as in (6)b., which is very productive, and an indirect causative, as in (6)c., which may not be productive. The indirect causative is discussed further in section 3.1.3., below. (6) a. jɛ́ 'eat' b. jés 'feed (directly, as a baby)' c. jésì 'feed (indirectly, as in 'give to eat')' The Abo causative is clearly descended from Proto-Bantu causative *-i-/ici. Abo's direct causative is quite similar to its Basaá cognate (¨-s); but the indirect is more different (¨-h-a/¨-s-a). 3.1.1. Direct Causative (¨ -(V)s) In vowel-final stems (where both vowels are the same, if two are present), the causative is formed by adding -s. In CVV roots, the vowel is shortened and -s suffixed (CVVC is not an acceptable syllable structure in Abo3). In consonant-final stems, the causative is formed by suffixing -Vs, where the vowel is a copy of the first root vowel. On stems of the shape CVCVC ending in -s, no additional causative suffix is added. No examples of a causative of more than two syllables were found. It was 3 The only word which we have found that is close to this syllable shape is wâyn 'wine', clearly an English loan. not possible to add the causative suffix to a three-syllable vowel-final stem (e.g., sɔ́sìmɛ̀ 'beg (for favor, service)') or to a two-syllable consonant-final stem (e.g., súŋkán 'be last, late', wóŋgwán 'help'). The causative has no effect on the tone of the verb, i.e., the causative of a H tone verb will be H and the causative of a L tone verb will be L. The causative triggers vowel raising in monosyllabic roots and in disyllabic roots where both vowels are the same. Examples of regular causative formation are given in (7). (7) Regular causatives GLOSS VERB CAUSATIVE a. have bwè bwès b. arrive, come lɔ̀ lòs c. injure (someone, something) kwèè kwès d. catch, seize, arrest bwɛ̀ɛ̀ bwès e. sell fàà fès f. let someone enter, put something inside nímí nímís g. bathe tòndò tòndòs h. dig up fúlú fúlús i. refuse, forbid tɛ̀w tèwès j. add ɓát bétés k. extinguish, turn off (light) dímís dímís l. cover (transitive) kúghús kúghús m. clean (table, floor etc.) síŋís síŋís In disyllabic roots containing two different vowels, total vowel harmony does not always take place. When the first vowel is higher than the second, vowel harmony occurs. When the first vowel is the same height or lower than the second, no vowel harmony occurs. Vowel raising can apply to each of the vowels, but does not always apply to both. (8) Causatives of stems containing different vowels GLOSS harmony VERB CAUSATIVE a. cover búté bútús b. deceive, lie lòghà lòghòs no harmony c. remember kɔ̀ŋgè kòŋgès d. count sɔ̀ŋsɛ̀ sɔ̀ŋsès 3.1.2. Irregularities In some CVV roots, the vowel shortens, an extra consonant appears, and the -Vs allomorph of the causative suffix is used. A few CV roots also gain an extra consonant and follow the consonant-final stem pattern for causative suffixation. Examples of these two types of irregularities are given in (9). At least some of the consonants that surface in the causative forms can be attributed to a historically lost consonant that is present in the reconstructed form of the verb (Bastin and Schadeberg 2011). In these cases, the reconstructed consonant is given in the last column in (9). A few monosyllabic verbs use i, in place of a copy vowel. These may represent a more conservative form of the extension, reconstructed as *-i-/-ici in Proto-Bantu (Schadeberg 2003). (9) Irregular causatives RECONSTRUCTED GLOSS VERB CAUSATIVE FINAL C added C a. swallow mɛ̀ɛ̀ mèlès *d b. sleep, fall asleep láá lélés *d c. rot bɔ̀ɔ̀ bòlòs *d d. blow fúú fúlús ? e. press, iron, grind, crush séé séghés ? f. look at, look after táá téghés ? g. wash sɔ̀ɔ̀ sòghòs *k formed with -is h. write cèè cèlìs i. full, be yéé yélís j. feed jés jésís k. close kwès kwèsìs 3.1.3. Indirect Causative (-si) The table in (10) shows all attestations of the indirect causative. The presence of a final i makes the Abo indirect causative appear a more conservative reflex of the Proto-Bantu causative than the Abo direct causative, since the causative is reconstructed with a high final vowel (*-i-/-ici) in Proto-Bantu (Schadeberg 2003), which seems to have been lost in the direct causative. (10) Indirect causatives DIRECT CAUSATIVE INDIRECT CAUSATIVE GLOSS VERB a. come fè b. eat jɛ́ jés jésí c. excrete, defecate nyɛ̀ nyès nyɛ̀sì d. cry yɛ̀ yès yɛ̀sì e. full, be yéé yélís yésí fèsì It is not clear from this limited set of examples whether vowel raising is part of the indirect causative or not. One verb shows vowel raising while others do not. The raising in (10)b could be due to analogy with the direct causative of this particular form, but this does not explain why it would not happen across the board. Another possible explanation is that for the verb displaying vowel raising, the causative is being formed on a different stem (for instance, on the direct causative or the resultative, which each independently trigger vowel raising). A second difference between the direct and indirect causative is seen in (10)e: the consonant that appears in the direct causative is not present in the indirect causative. It could be that the consonant is present underlyingly but is deleted due to the following syllable, or it may be that the indirect causative is formed on the CVV base and not on the CVC base. 3.2. Reciprocal (-na) The reciprocal extension creates a reciprocal verb, and can occasionally lend a special lexicalized meaning to the base verb, as seen in (11). (11) a. ɓá !nɔ́k wɛ́ 3PL hear 2SG 'they hear you' b. ɓá !nók-ná 3PL hear-RECIP 'they hear each other, they get along' The Abo reciprocal is cognate to Basaá (-n-a), and to Proto-Bantu *-an. The reciprocal is often used in combination with the associative, which may be a source of confusion between these two forms. This could account for -n appearing in some associative forms and -l in some reciprocal forms. The reciprocal is formed by the addition of a -na suffix, which may be added to either a vowelfinal or consonant-final stem, as shown in (12).4 Based on the limited number of examples attested, the reciprocal does not appear to condition vowel raising on the verb. Instances where there is vowel raising e.g., (12)b, may be due to the reciprocal being in the resultative form. The reciprocal has no effect on the tone of the verb, i.e., the reciprocal of a H tone verb will be H and the reciprocal of a L tone verb will be L. (12) Reciprocals GLOSS VERB RECIPROCAL RECIPROCAL GLOSS a. see nɛ́ nɛ́ná meet b. hear nɔ́k nókná get along (lit., hear each other) c. hit, beat ɓòm ɓòmnà, ɓòmà hit each other d. go, walk kɛ̀ kɛ̀nà take 3.3. Associative (-(l)a) The associative licenses the expression of an instrumental or comitative argument of the verb. The associative is most consistently and clearly identifiable in clauses relativizing on the instrumental/ comitative argument, as in (13). (13) pàà í là mɛ́ machete CL9 REL 1SG 'the machete I cut the grass with' kɛ́-lá cut-ASSOC bikáy grass.PL The associative can appear in other constructions, in particular in combination with other derivational suffixes, such as the reciprocal, as in (14). (14) ɓá ságh-á-ná 3pl dance-ASSOC-RECIP 'they danced together/with each other' It can have a more general argument-adding function with idiosyncratic semantics, such as ablative, as in (15). 4 More work is needed to determine the extent of productivity and any variation in form of this suffix. (15) yɔ̌ŋ 'take' yɔ̀ná 'take from' No cognate for this associative form is present in Basaá, nor is it reconstructed in Proto-Bantu. The associative is formed with the addition of a -(l)a suffix. Consonant-final stems normally add -a. In the associative form of monosyllabic vowel-final roots, a consonant usually surfaces between the root and the extension. This consonant is either underlying (similar to what was seen in the causative) or an added -l. In disyllabic vowel-final stems, the final vowel is normally just changed to -a to form the associative. Examples of various associatives are given in (16). Some roots irregularly take the -la allomorph of the associative extension, and in some cases a second vowel is irregularly deleted. As alluded to in §1.1, the /k/→[gh] change seen in (16i) is a regular intervocalic phonological process. (16) Associatives of various stems VERB ASSOCIATIVE a. GLOSS eat jɛ́ jélá, jéá C present in causative? no b. give birth bwáá bwélá yes c. go, walk kɛ̀ kɛ̀là, kɛ̀nà no d. cut, cut away (grass) kɛ́ɛ́ kɛ́lá yes e. heat bápsɛ́ ɓépsá n/a f. call béghé bélá n/a g. carry (on head, back, in hand) bɛ̀ghɛ̀ bɛ̀ghà n/a h. scold kímí kímlá n/a i. dance sák sághá n/a j. close kwès kwèlà n/a k. buy wàn(d) wàndà n/a l. clean (table, floor etc.) síŋís síŋlá n/a m. extinguish, turn off (light) dímís dímsá n/a In the cases where the same consonant surfaces in the associative and in the causative, we can presume that this consonant is underlyingly – or at least diachronically – part of the root. When an l appears in the associative for which there is no evidence of in the causative form, we must analyze -la as an allomorph of the associative. The l may have deleted following consonants, historically. The l could have originated from another suffix, such as the applicative, and been reanalyzed with the final -a as an associative. No clear pattern has been discovered regulating when vowel raising occurs in the associative and when it does not. Forms with raised vowels could be due to analogy on the other forms, or due to the combination of two forms. The associative has no effect on the tone of the verb, i.e., the associative of a H tone verb will be H and the associative of a L tone verb will be L. 3.4. Passive (-(l)abɛ) The passive extension in Abo causes a patient to be promoted to subject, as in (17). An agent may be optionally expressed in an oblique. (17) bɛ́t → 'to rise' à bɛ́t-ábɛ́ 'it was brought up (e.g., upstairs)' The passive shows semantic and functional overlap with the resultative (stative) form. The passive may be used in (at least) the simple present and past tenses. The Abo passive is cognate to Basaá (¨-a, ¨-b-a). The passive does not appear to be a reflex of a reconstructed Proto-Bantu extension but a similar form, a passive with the shape *-(a)b(e), is reconstructed for zones A and B. The Abo passive reflects the form of the middles that Bostoen and Nzang-Bie (2010) claim developed into passives in Bantu A70 languages by stacking of the middle + associative/reciprocal extensions. In monosyllabic vowel-final roots, the passive is formed by the addition of a -labɛ suffix. In polysyllabic vowel-final roots, on the other hand, the final vowel is truncated, and an -abɛ suffix is added. Consonant-final roots take the -abɛ suffix. The regular /k/→[gh] alternation can be seen in (16e). As in (16m) above, the second vowel of dímís 'extinguish' is deleted in this form; presumably this is a frozen causative which may explain the unexpected behavior of the vowel. Examples of regular passives are given in (18). VERB PASSIVE a. GLOSS catch, seize, arrest bwɛ̀ bwɛ̀lábɛ́ b. eat jɛ́ jɛ́lábɛ́ c. write cèè cèlábɛ́ d. say kàà kàlábɛ́ e. break (something hard, e.g. wood, glass) ɓók f. bless nàm nàmábɛ́ g. call béghé béghábɛ́ h. measure, weigh mɛ̀nɛ̀ mɛ̀nábɛ́ i. extinguish, turn off (light) dímís dímsábɛ́ j. help wóŋgwán wóŋgwánábɛ́ ɓóghábɛ́ (18) Regular passives The passive does not normally trigger vowel raising. The passive has no effect on root tone; the tones on the passive stem follow general patterns of inflection and metatony (see Hyman and Lionnet 2011) as seen in examples (19) and (20), where tense is marked tonally. The two syllables of the passive suffix pattern together tonally.5 (19) dí kà-lábɛ́ 'It is said' (20) dí ká-làbɛ̀ 'It was said' 3.4.1. Irregularities Irregularities were observed in passive forms of certain verbs. A few passives are found with raised vowels, as in (21)g., although the same vowels do not normally raise in the passive. Some CV(V) roots have a consonant (other than the expected l) surface before the passive suffix, as in (21)ad. Some of these consonants can be attributed to root-final consonants that were lost historically, but for others there is no evidence of this. In addition, the unexpected consonants are not always consistent between causative and passive forms of the same verb. A few CVC(V) roots take the -labɛ allomorph rather than the expected -abɛ allomorph, as in (21)e-f. Prenasalized stops (e.g., (21)h.) seem always to take -labɛ form. 5 The only example we have of a passive of more than three syllables is a H verb, so all four syllables of the passive are H. I presume a four syllable passive of a L verb would have the pattern LLHH, but this will have to be confirmed with additional data. (21) Irregular passives GLOSS VERB PASSIVE a. go, walk kɛ̀ kɛ́nàbɛ̀, kɛ́làbɛ̀ b. see nɛ́ nɛ́nábɛ́ c. wash sɔ̀ sɔ̀ghábɛ́ d. pay càà càghàbɛ̀ e. send wɔ́m wɔ́mlábɛ́ f. suffer tàk tàklábɛ́ g. hide (something), conceal wòt wùtábɛ́ h. bathe tòndò tòndlábɛ́ i. roll, fold, wrap up fóghó fólábɛ́ 3.5. Applicative (¨ -V) and Resultative (¨ -í/v́) The applicative and the resultative (aka stative) are discussed together in this section because they are often formally identical segmentally in Abo, although they remain tonally distinct. There is much overlap in use between the applicative and the resultative, as is also seen between the causative and the associative. The applicative in Proto-Bantu, *-ɪl, is likely the source of both the high vowel/vowel raising and the recurring l in both Abo applicatives and resultatives. The applicative is derivational, and adds an argument (generally a beneficiary), as shown in (23). (22) à wá!´n mákàkò 3SG buy.PST crab.PL 'He bought crabs' (23) à wén!dé mán 3SG buy.APPL.PST child 'He bought the child crabs' màkàkò crab.PL The Abo applicative is cognate to the Basaá applicative (¨-l). The resultative should be considered tense/aspect inflectional morphology. It can be used with various derived and underived stems, including applicatives. (24) mɛ̀ báŋà shɔ̀rtì 1SG sew.PST shirt 'I sewed the shirt' (25) dí bàŋé CL5 sew.RESULT 'It is sewn' (26) à wèndé 3SG buy.RESULT 'He bought crabs' màkàkò crab.PL The form that we call the resultative is cognate to the Basaá stative (¨-i). The resultative/stative in Abo and Basaá bear no resemblance to their Proto-Bantu counterparts. Both the applicative and the resultative are formed by the addition of final vowel (either -i or a copy vowel). In both forms, underlying or historic consonants in a CV(V) root will resurface. A nonhistoric -l sometimes appears in both forms. A comparison of applicative and resultative forms for several verbs is given in (27). (27) Resultatives and applicatives VERB APPLICATIVE RESULTATIVE a. GLOSS see nɛ́ nɛ́ nɛ́ní b. cut, cut away (grass) kɛ́ɛ́ kélí kélí, kélé c. fold fóó fóó fóló d. do, make sáá sélé séé e. cover búté bútú bútú f. lie down nàŋà níŋí nèŋé g. grill, barbecue, roast ɓòp ɓòpò ɓòpó h. leave behind yék yéghé yéghé, yéghí i. close kwès kwésí kwésí j. cover (transitive) kúghús kúghú kúghú Both the applicative and the resultative trigger vowel raising. The resultative adds a H tone suffix to the verb. If the verb root is L toned, the resultative will be L-H; if the root is H toned, the resultative will be H-H. Resultative forms do not participate in metatony (Hyman and Lionnet 2011). By contrast, the applicative has no effect on the tone of the verb, i.e., the applicative of a H tone verb will be H and the applicative of a L tone verb will be L. 3.5.1. Untangling the Two Segmental Forms As an explanation for the significant overlap in segmental form between these two extensions, I propose that the resultative historically had an -i suffix, the applicative had an -lV suffix, and that these two verb forms have gotten mixed up in modern Abo. Slightly more -i forms are present in the resultative than in the corresponding applicatives, and very slightly more -l forms are present in the applicatives than in the corresponding resultatives. Cognate morphemes in Basaá support this weak statistical tendency that it was the resultative that originally had an -i suffix. The reconstructed ProtoBantu applicative contains l, although it has a vowel which would correspond to Abo -el (Schadeberg 2003). 3.6. Gerundive (-ak) The gerundive form in Abo is used to form nonfinite verbs, deverbal nominals, and imperfectives. Examples are given in (28)-(29). (28) sák → 'to dance' mɛ̀ kɛ́ íyǎ ín!yú mà sáɡhâk 'I went there for dancing (I went there to dance)' (29) wáŋ → 'to read' à bɔ́tà wàŋgâk 'he began to read' This extension is related to the Proto-Bantu 'repetitive' *ag ~ *ang, and to the Basaá 'imperfective' -g ~ -ag. Spellenberg (1922) and Atindogbé (1996) call the verb form bearing this extension in Abo the infinitive. The gerundive is formed by the addition of an -ak or -lak suffix. The suffix takes the form -Vgha with certain disyllabic roots. Underlying or historic consonants in CV(V) roots resurface when this extension is added. Examples of gerundives for verbs of various shapes are given in (30). Gerundive suffix vowels sometimes participate in vowel harmony. It is unclear whether the gerundive conditions vowel raising. The gerundive extension does not have any effect on the tone of the verb, i.e., the gerundive of a H tone verb will be H and the gerundive of a L tone verb will be L. (30) Gerundives GLOSS VERB GERUNDIVE a. eat jɛ́ jɛ́ghɛ́k b. say kàà kàlàk c. break (something hard, e.g. wood, glass) ɓók bóghôk d. grill, barbecue, roast ɓòp ɓóplàk e. call béghé béglàk f. cover búté bútlàk g. try kèghà kéghàk h. begin bɔ̀tà botagha i. heat bápsɛ́ bápsèghè j. clean (table, floor etc.) síŋís síŋsàk k. close kwès kwèlàk 4. Combining Derivational Suffixes 4.1. Contentful Combinations While some combinations are possible, all derivational extensions cannot combine freely. Unsurprisingly, the resultative, being essentially inflectional in nature, combines freely with the true derivational extensions, as does the subjunctive. Not only are combinations of derivational extensions limited, when they do combine, the combination can be hard to see due to the similarity of many of the forms. Examples of combinations found to be possible are given in examples (31)-(34). (31) shows an associative reciprocal. (31) ASSOCIATIVE + RECIPROCAL ɓá ságh-á-ná 3PL dance-ASSOC-RECIP 'They danced with each other.' In (32), the applicative and the causative are combined, in that order. However, there is a structural ambiguity between the beneficiary and the causee; so the two readings given in the gloss are both possible. (32) APPLICATIVE + CAUSATIVE mɛ̀ káá ké-lé-s nyɛ́ wɛ̀ brètì 1SG FUT cut-APPLIC-CAUS 3SG 2SG bread 'I will make him cut bread for you / I will make you cut bread for him.' In (33)a, a sentence requiring both the associative and applicative meanings to be encoded in the verb in order to be grammatical, shows that a morphological applicative or associative alone is acceptable. However, when both the applicative and associative are morphologically expressed together on the verb, in either order, as in (33)b, the sentence becomes unacceptable. (33) ASSOCIATIVE + APPLICATIVE a. ílɛ̀n dì là mɛ́ ké-lé/ké-lá wɛ́ brètì knife CL5 REL 1SG cut-APPLIC/cut-ASSOC 2SG bread 'The knife with which I cut the bread for you.' b. *ílɛ̀n dì là mɛ́ ke-le-la/kɛ-la-lɛ wɛ́ brètì knife CL5 REL 1SG cut-APPLIC-ASSOC/cut-ASSOC-APPLIC 2SG bread [intended reading: 'The knife with which I cut the bread for you.'] The example in (34)a shows several morphological possibilities for combining the associative and gerundive meanings. The associative may be followed by the gerundive, or may stand alone, and either of these forms may have an additional gerundive ending (or two) added. A gerundive alone, however, may not stand alone in this syntactic construction, as shown in (34)b. (34) associative + gerundive a. ílɛ̀n á bɔ́tà mɛ́ kɛ́-lɛ́-k/ké-là/kɛ́-lɛ́-gh-ɛ́k/kɛ́-lá-gh-ák dì brètì knife 3SG began 1SG cut-ASSOC-GER/cut-ASSOC/cut-ASSOC-GER-GER/cut-ASSOC-GER-GER CL5 bread 'The knife he began cutting with.' b. *ílɛ̀n á bɔ́tà mɛ́ kɛ-gh-ɛk6 dì brètì knife 3SG began 1SG cut-GER-GER CL5 bread [intended reading: 'The knife he began cutting with.'] A rough summary of the order of extensions is given in (35). The associative and applicative occur fairly close to the verb root, but their relative order has not yet been determined. The passive, reciprocal, and causative occur somewhat further from the root, but again, their relative order has not been determined so far. The gerundive falls consistently outside the other extensions. (35) ROOT - Associative Applicative - Passive Reciprocal Causative - Gerundive No evidence was found that suffixes could be reordered to reflect scope. Rather, scope was ambiguous, as in (32), suggesting a templatic ordering principle. 4.2. Non-contentful Combinations In the previous section, we have seen that extensions cannot not be stacked up in an agglutinating fashion to create complex meanings to a very great degree, and in some cases, the semantic content of more than one extension can be morphologically expressed by only one of the extensions. In this section, practically the opposite phenomenon is demonstrated, in which multiple suffixes stack up phonologically, but have no apparent effect on the semantics or syntax of the sentence. The forms seen in (36) and (37) below were offered spontaneously when a simple gerundive or associative, respectively, were being elicited. Most have synonymous shorter forms possible, but some do not. 6 *kɛghɛk (cut-GER-GER) is acceptable as a gerundive but cannot be used in this construction without the presence of the adposition ni/nik 'with' to license the instrument. (36) 'Long' gerundives GLOSS VERB GERUNDIVE a. rise, go up bɛ́t bétàghàk (cf. bétàk) b. refuse, forbid tɛ̀w tɛ̀wàghàk, tɛ̀wɛ̀̀ghɛ̀k (*tɛ́wɛ̀k) d. extinguish, turn off (light) dímís e. exchange fèŋsà féŋsàghàk (*fèŋsàk) f. count sɔ̀ŋsɛ̀ sɔ́ŋsɛ́ghɛ́k (*sɔŋsek, *sɔŋsak) g. catch, seize, arrest bwɛ̀ bwɛ̀lághak h. call béghé béglàghàk (cf. béglàk) i. hide (something), conceal wòt wútlàghàk GLOSS VERB ASSOCIATIVE a. catch, seize, arrest bwɛ̀ bwé!láná b. go, walk kɛ̀ kɛ̀lànà c. refuse, forbid tɛ̀w tewana d. buy wàn(d) wàndànà e. count sɔ̀ŋsɛ̀ sɔ̀ŋsàghànà, sɔ̀ŋsèlànà f. clean (table, floor etc.) síŋís síŋlághá g. wash sɔ̀ɔ̀ sòwànà, sòghàna dímsèghèk, dímsàghàk (*dimsek, dimsak) (37) 'Long' associatives There was no difference in meaning or use between the shorter and longer forms, so there is no apparent syntactic or semantic explanation for the multiple copies of extensions in these forms. It would also be difficult to argue for a phonological motivation, because in many cases the parallel shorter form exists. Based on the forms in the tables above, the following generalizations about morph ordering can be made: • -na can follow -gha, -la (37)a, b, e • -na cannot be repeated • -gh/k can be repeated (36) • -la cannot follow -na • -gha can follow -la (37) f Thus we have the template: -la-gha*-na, where * indicates one or more copies. Assuming that these are empty versions of the contentful extensions discussed above, this gives us the speculative affix order shown in (38), which is somewhat different from the one seen for contentful extensions in (35), above. (38) ROOT - 'Associative/Applicative' - 'Gerundive' - 'Reciprocal/Associative' 5. Discussion 5.1. Summary To summarize, this paper has shown that Abo uses a set of verb extensions that tend to be reduced in form. These include the applicative, associative, causative (direct and indirect), gerundive, passive, reciprocal, and resultative. Expression of morphological categories in Abo is accomplished through segmental means, tonal changes, and/or vowel raising and vowel harmony. Of particular note, the segmental forms of the applicative and the resultative appear to be intermixing, while they remain tonally distinct. We have seen that in some cases, consonants that have been historically lost in root forms resurface under affixation. However, in other cases, insertion of an -l- in combination with several of the extensions occurs where there is no evidence for a historic root-final consonant. Finally, we have observed another phenomenon whereby one or more semantically empty morphs (of the form -l-, -n-, or -g/k-) may be 'stacked up' before a contentful associative or gerundive extension. 5.2. Comparative Implications Bantu languages of homeland area (the Nigeria/Cameroon border), where Abo is located, tend to be less conservative and have more non-Bantu features, as compared to other Bantu languages (Nurse & Philippson 2003). This proves to be the case for Abo, which shows significant changes in the shape and/or effects of verb extensions, does not have a final vowel morpheme requirement for verbs, and has a vowel raising process which takes place with certain suffixes. In these broad respects, Abo resembles the related language Basaá, but the details of its verbal extension system are different. A comparison of extensions in Abo, Basaá, and reconstructed Proto-Bantu forms is given in (39). (39) Comparison of extensions Extension Proto-Bantu Basaá (after Schadeberg 2003) (Schadeberg 2003) (Hyman 2003) causative dative (applicative) impositive neuter positional (stative) associative (reciprocal) repetitive extensive tentive (contactive) separative (reversive) passive *-i-/-ici *-ɪl*-ɪk*-ɪk*-am*-an*-ag- ~ -ang*-al*-at*-ʊl-; -ʊk*-ʊ-/-ibʊ- ¨-s; ¨h-a/¨-s-a ¨-l, -n-ɛ – – ¨-í -n-a -g [k], -ag [ak] – – ¨-l, -l ¨-a, ¨-b-a, -a, -n-a Abo ¨-(V)s; -si ¨-V – – ¨-í/v́ -na -ak – – – -(l)abɛ In terms of comparison to its neighbor, Basaá, Abo lacks the reversive, reflexive, and habitual morphemes found in Basaá, but has an associative morpheme which Basaá lacks. Of the extensions which are cognate in the two languages, the forms of the morphemes are generally very similar. However, Abo passive, applicative, and causative extensions can have the same form when added to a longer root as they do when they are added to a CV root, while their Basaá counterparts take different forms in these situations. In terms of comparison with Bantu more generally, some Abo extensions are clearly reflexes of Proto-Bantu extensions, while others are quite different. Abo has an associative extension which is not reconstructed for Proto-Bantu. It is possible that both the Abo reciprocal n and associative l may have developed from Proto-Bantu associative/reciprocal *-an-. The stative/resultative and passive in Abo and Basaá bear no resemblance to their Proto-Bantu counterparts. The applicative in Proto-Bantu, *-ɪl, is likely source of both the high vowel/vowel raising and the recurring l in Abo applicatives and resultatives. In Bostoen and Nzang-Bie's (2010) analysis, the passive in A70 languages developed from the middle and associative/reciprocal. The Abo passive form is very similar to the middle they discuss, although the associative/reciprocal component is not present. Furthermore, the non-compositional result of stacking up multiple extensions discussed by Bostoen and Nzang-Bie's (2010) is quite applicable to two phenomena seen in Abo. First, the l, which may originate in an applicative, is found in combination with many extensions. Second, the apparently semantically empty l, n, g/k are found with multiple copies in the gerundive and the associative. Directions for future research include more work on the combinatorics and semantics of these morphemes, and additional investigation into the phenomenon of multiple 'inactive' suffixes. References Atindogbé, Gratien. 1996. Bankon (A40): éléments de phonologie, morphologie et tonologie. Köln: Rüdiger Köppe Verlag. Bastin, Yvonne and Thilo C. Schadeberg. 2011. Bantu Lexical Reconstructions 3. Online database: http://www.metafro.be/blr, accessed March-May 2011. Bostoen, Koen and Yolande Nzang-Bie. 2010. On how "middle" plus "associative/reciprocal" became "passive" in the Bantu A70 languages. Linguistics 48: 1255-1307. Coupez, André, Yvonne Bastin and E. Mumba. 1998. Bantu Lexical Reconstructions 2. Database. CBOLD. Guthrie, Malcolm. 1953. The Bantu Languages of Western Equatorial Africa. Oxford University Press. Hyman, Larry M. 2003. Basaá (A43). In: Nurse, D. and G. Philippson, eds. The Bantu Languages. Routledge. Hyman, Larry M. and Florian Lionnet. 2011. Metatony in Abo (Bankon), A42. Presented at University of Maryland 42nd Annual Conference on African Linguistics. Janssens, Baudouin. Phonologie Historique du Basaa. 1982. Dissertation. Universite Libre de Bruxelles, Faculte de Philosophie et Lettres. Janssens, Baudouin. 1986. Eléments de phonologie et de morphologie historique du basaa (bantou A43a). In: Africana Linguistica X: 147-212. Lamberty, Melinda. 2002. A Rapid Appraisal Survey of the Abo and Barombi Speech Communities, South West and Littoral Provinces, Cameroon. SIL International. Lewis, M. Paul (ed.), 2009. Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Sixteenth edition. Dallas, Tex.: SIL International. Online version: http://www.ethnologue.com/, accessed May 8, 2011. Meussen, Achille E. 1967. Bantu grammatical reconstructions. Africana Linguistica 3: 80-122. Nurse, Derek. and Gerard Philippson. 2003. The Bantu Languages. Routledge. Schadeberg, Thilo C. 2003. Derivation. In: Nurse, D. and G. Philippson, eds. The Bantu Languages. Routledge. Spellenberg, Friedrich. 1922 [Reprinted 1969]. Die Sprache der Bo oder Bankon in Kamerun mut Beiträgen von Carl Meinhof und Johanna Vöhringer. Nendeln: Kraus.