* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Epidemiology of Seafood-Associated Infections in the United States

Human cytomegalovirus wikipedia , lookup

Sarcocystis wikipedia , lookup

Clostridium difficile infection wikipedia , lookup

Herpes simplex wikipedia , lookup

African trypanosomiasis wikipedia , lookup

Traveler's diarrhea wikipedia , lookup

West Nile fever wikipedia , lookup

Dirofilaria immitis wikipedia , lookup

Herpes simplex virus wikipedia , lookup

Schistosomiasis wikipedia , lookup

Sexually transmitted infection wikipedia , lookup

Leptospirosis wikipedia , lookup

Trichinosis wikipedia , lookup

Oesophagostomum wikipedia , lookup

Bioterrorism wikipedia , lookup

Middle East respiratory syndrome wikipedia , lookup

Hepatitis C wikipedia , lookup

Ebola virus disease wikipedia , lookup

Hepatitis B wikipedia , lookup

Anaerobic infection wikipedia , lookup

Eradication of infectious diseases wikipedia , lookup

Neonatal infection wikipedia , lookup

Henipavirus wikipedia , lookup

Gastroenteritis wikipedia , lookup

Marburg virus disease wikipedia , lookup

Foodborne illness wikipedia , lookup

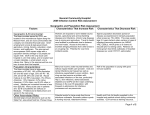

CLINICAL MICROBIOLOGY REVIEWS, Apr. 2010, p. 399–411 0893-8512/10/$12.00 doi:10.1128/CMR.00059-09 Copyright © 2010, American Society for Microbiology. All Rights Reserved. Vol. 23, No. 2 Epidemiology of Seafood-Associated Infections in the United States Martha Iwamoto,* Tracy Ayers, Barbara E. Mahon, and David L. Swerdlow Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................................................399 PATHOGENS RESPONSIBLE FOR SEAFOOD-ASSOCIATED INFECTIONS..............................................400 Bacteria ....................................................................................................................................................................400 Vibrio species .......................................................................................................................................................400 Salmonella.............................................................................................................................................................400 Shigella species ....................................................................................................................................................401 Clostridium botulinum..........................................................................................................................................401 Other toxin-forming bacteria ............................................................................................................................401 Viruses ......................................................................................................................................................................401 Norovirus..............................................................................................................................................................401 Hepatitis A virus .................................................................................................................................................402 Parasites...................................................................................................................................................................402 Helminths.............................................................................................................................................................402 Protozoa ...............................................................................................................................................................402 EPIDEMIOLOGY OF SEAFOOD-ASSOCIATED INFECTIONS.......................................................................403 Sources of Data and Methods...............................................................................................................................403 Summary of Seafood-Associated Outbreaks and Infections .............................................................................403 General epidemiologic characteristics .............................................................................................................403 Outbreaks and infections caused by bacteria .................................................................................................405 Outbreaks caused by viruses.............................................................................................................................408 Outbreaks caused by parasites .........................................................................................................................408 DISCUSSION ..............................................................................................................................................................408 REFERENCES ............................................................................................................................................................410 seal and whale), fish eggs (roe), and crustaceans (e.g., shrimp, crab, and lobster). Some seafood commodities are inherently more risky than others owing to many factors, including the nature of the environment from which they come, their mode of feeding, the season during which they are harvested, and how they are prepared and served. Fish, mollusks, and crustaceans can acquire pathogens from various sources. All seafood can be susceptible to surface or tissue contamination originating from the marine environment. Bivalve mollusks feed by filtering large volumes of seawater. During this process, they can accumulate and concentrate pathogenic microorganisms that are naturally present in harvest waters, such as vibrios. Contamination of seafood by pathogens with a human reservoir can occur when growing areas are contaminated with human sewage. Outbreaks of seafood-associated illness linked to polluted waters have been caused by calicivirus, hepatitis A virus, and Salmonella enterica serotype Typhi (22, 46, 55, 64). Identified sources of seafood contamination have included overboard sewage discharge into harvest areas, illegal harvesting from sewage-contaminated waters, and sewage runoff from points inland after heavy rains or flooding. Additionally, seafood may become contaminated during handling, processing, or preparation. Contributing factors may include storage and transportation at inappropriate temperatures, contamination by an infected food handler, or cross-contamination through contact with contaminated seafood or seawater. Adequate cooking kills most pathogens; however, unlike other foods, such as meat and poultry, that are usually fully cooked, seafood is often consumed raw or prepared in ways that do not kill organisms. INTRODUCTION Seafood is a nutrient-rich part of a healthful diet, and seafood consumption is associated with potential health benefits, including neurologic development during gestation and infancy (17, 28, 31, 32) and reduced risk of heart disease (20, 37, 38, 48). Seafood consumption has increased in the United States in recent decades, reaching a high during the past decade: the average American now eats approximately 16.5 pounds of seafood each year, compared with 10 to 12 pounds during the 1980s (49). However, along with the nutrients and benefits derived from seafood consumption come the potential risks of eating contaminated seafood. Chemicals, metals, marine toxins, and infectious agents have been found in seafood. Infectious agents associated with food-borne illness include bacteria, viruses, and parasites, and the illnesses caused by these agents range from mild gastroenteritis to life-threatening syndromes. Seafood is responsible for an important proportion of food-borne illness and outbreaks both in the United States and worldwide. Although seafood is also an important vehicle for marine toxins and chemical contamination, a review of these syndromes is beyond the scope of this article; they have been described recently elsewhere (2, 62). Seafood includes mollusks (e.g., oysters, clams, and mussels), finfish (e.g., salmon and tuna), marine mammals (e.g., * Corresponding author. Mailing address: Enteric Diseases Epidemiology Branch, CDC, 1600 Clifton Road NE, Mailstop D-63, Atlanta, GA 30333. Phone: (404) 639-4745. Fax: (404) 639-2206. E-mail: [email protected]. Americans are eating 65% more seafood since the 1980's 399 400 IWAMOTO ET AL. Seafood-associated infections are caused by a variety of bacteria, viruses, and parasites. This diverse group of pathogens results in a wide variety of clinical syndromes, each with its own epidemiology. In this article, we review the biology, clinical features, and public health aspects of pathogens most commonly associated with seafood. We then describe the epidemiology of seafood-associated infections in the United States, specifically reviewing national seafood-associated outbreaks reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) during 1973 to 2006 to explore whether the occurrence of outbreaks is changing, whether new sources have been emerging, and whether prevention measures have been effective in decreasing or controlling risk. PATHOGENS RESPONSIBLE FOR SEAFOODASSOCIATED INFECTIONS Bacteria Vibrio species. Vibrio organisms are Gram-negative, halophilic bacteria that are widespread and naturally present in marine and estuarine environments. Environmental factors influence their growth, and their numbers are highest when the water is warm. The genus Vibrio includes 30 species, of which at least 14 are recognized as pathogenic in humans. Vibrio infections are acquired through ingestion of contaminated seafood or through exposure of an open wound to seawater. Vibrio parahaemolyticus and Vibrio vulnificus are the species most commonly associated with reported infection. V. parahaemolyticus has been associated with sporadic infections and outbreaks of gastroenteritis, while V. vulnificus infections occur almost exclusively as sporadic cases in the United States. Clinical features most often associated with V. parahaemolyticus infection include watery diarrhea, abdominal cramps, nausea, and vomiting; wound infections and septicemia occur less commonly (18, 39, 45). V. vulnificus is particularly virulent, especially among patients with liver disease and iron storage disorders, who are at increased risk of invasive disease (4, 33, 39). V. vulnificus infections can lead to sepsis and severe wound infections (33, 39, 50, 60). Severe infections, such as bloodstream and wound infections, require prompt antimicrobial therapy. The case fatality rate is about 50% for bloodstream infections and 25% for wound infections (21, 33, 35, 60). Laboratory diagnosis is made by isolation of the organism from clinical specimens, including blood, stool, and wound samples. Because they can be overlooked on standard agar plates, Vibrio organisms in stool or wound samples are best identified on selective media, such as thiosulfate-citrate-bile salts-sucrose (TCBS) agar (1, 34). Cases of Vibrio infections have a marked seasonal distribution; most occur during summer and early fall, corresponding to the period of warmer temperatures. Almost all cases of food-borne Vibrio infection are associated with a recent history of seafood consumption, primarily raw oyster consumption. Like other organisms found in water, vibrios can be concentrated in the tissues of filter-feeding bivalve mollusks. Measures to prevent food-borne Vibrio infections include consumer education regarding the dangers of eating raw or undercooked shellfish, particularly among persons with medical conditions, such as liver disease, that predispose them to severe illness. CLIN. MICROBIOL. REV. Thoroughly cooking shellfish and preventing raw seafood from cross-contaminating other foods are effective measures for consumers to reduce risk (25). Regulatory control measures have included monitoring of harvest waters and microbiological sampling of oysters. However, it is important that the presence of vibrios is not associated with fecal contamination. Therefore, monitoring waters for fecal coliform bacteria is not effective as an indicator of the presence of Vibrio in harvest environments. Finally, postharvest processing methods, such as high-pressure treatment, irradiation, quick-freezing, and pasteurization, are available to make oysters safer. Vibrio infections are reportable to state health departments, and traceback of oysters associated with human Vibrio infection is strongly encouraged (16). Salmonella. Salmonellae are Gram-negative bacilli. Approximately 2,500 Salmonella serotypes have been identified, causing a variety of clinical syndromes ranging from asymptomatic carriage to invasive disease (6). Salmonella most commonly causes acute gastroenteritis, with symptoms including diarrhea, abdominal cramps, and fever. Other clinical manifestations can include enteric fever, urinary tract infections, bacteremia, and severe focal infections. Isolation of Salmonella organisms from cultures of stool, blood, or other clinical samples is diagnostic; isolates are referred to public health laboratories for serotype characterization. Salmonella is a leading cause of food-borne illness, causing approximately 1.4 million illnesses annually in the United States (44). Incidence is highest among infants and the elderly, and infections are more likely to occur during summer and early fall (52). Each Salmonella serotype has its individual biology and ecological niche. Many natural reservoirs for the different Salmonella serotypes have been identified. Humans are the only known reservoir for Salmonella serotype Typhi; many animal hosts (birds, reptiles, and mammals) serve as reservoirs for nontyphoidal serotypes. With improvements in sanitation over the past several decades, Salmonella serotype Typhi went from being the leading cause of Salmonella infection to becoming relatively uncommon. However, nontyphoidal Salmonella infections have emerged as a public health problem since the 1950s (52, 63, 64). Routes of Salmonella transmission include food-borne and waterborne routes, person-to-person contact, and contact with animals, particularly reptiles. Most cases of nontyphoidal salmonellosis are caused by ingestion of contaminated food, and outbreaks have been associated with a wide range of food vehicles in the United States. Seafood-associated outbreaks have been caused by fish, shrimp, oysters, and clams. Studies to determine the prevalence of Salmonella spp. in oysters from domestic bays and testing of sampled oysters from domestic seafood samples by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) have demonstrated the presence of salmonellae in a variety of fish and shellfish, including seafood intended for consumption without further preparation upon distribution, requiring minimal cooking, and shellfish eaten raw (5, 30). Fish and shellfish can acquire Salmonella from polluted waters. Historically, sewage contamination of shellfish harvest beds led to large shellfish-associated outbreaks of Salmonella serotype Typhi infections. Control measures aimed at detecting contamination of harvest waters, such as monitoring fecal coliform counts in these waters, have been effective at reducing the risk of Salmonella contamination of seafood occurring before har- VOL. 23, 2010 vest. Additionally, seafood can become contaminated with Salmonella during storage and processing (7, 29). Salmonella infection can be prevented by adequate cooking, proper storage and processing after harvest, and avoidance of cross-contamination during seafood handling (24, 25). Shigella species. Shigella species are Gram-negative bacilli. Four species have been identified, and clinical presentations vary by species. Clinical manifestations of Shigella infection range from watery, loose stools to more severe symptoms, including fever, abdominal pain, tenesmus, and bloody diarrhea. Complications are rare and include seizures in young children, toxic megacolon, bacteremia, Reiter’s syndrome, and hemolytic-uremic syndrome. Diagnosis is made by isolation of Shigella from feces or rectal swabs. Cases occur worldwide, in endemic and epidemic forms. Most cases occur among children aged ⬍10 years. Humans are the primary reservoir of Shigella. Transmission occurs through direct or indirect contact with feces of infected persons. Shigella infection is highly communicable, because ingestion of as few as 10 viable organisms is sufficient for infection to occur. The low infectious dose contributes to the potential for large outbreaks. Outbreaks have been associated with person-to-person transmission in crowded or unhygienic environments and with ingestion of contaminated food and water. Foods can become contaminated during handling or preparation by an infected food handler. With seafood, contamination can occur if seafood is harvested from sewagecontaminated water, as occurred in an outbreak caused by consumption of raw oysters harvested from waters where sewage was dumped overboard from the oyster harvest boat (57). Shigella organisms can survive outside the host, but they are killed readily by cooking. Control strategies to prevent shigellosis associated with seafood have included monitoring of harvest water for fecal coliforms, prohibition of harvesting from sewage-contaminated areas, enforced control of dumping sewage overboard, and guidelines for seafood handling in restaurants. Clostridium botulinum. Clostridium botulinum is a sporeforming, anaerobic, Gram-positive bacillus that is widespread in the environment. The bacterium produces a potent neurotoxin under anaerobic, low-acid conditions. Seven types of botulism toxin have been identified; toxin types A, B, and E cause most human illnesses. Food-borne botulism is caused by the ingestion of food contaminated with preformed toxin produced by spores of C. botulinum. Botulism is characterized by an acute, symmetric, descending flaccid paralysis. Early signs and symptoms of botulism often include cranial nerve palsies, with diplopia, ptosis, slurred speech, and difficulty swallowing progressing to descending weakness and paralysis. Symptoms can progress to cause paralysis of the respiratory muscles, requiring ventilatory support. Cases of botulism are rare but serious; an estimated 60 food-borne cases occur each year in the United States (44). Most cases are sporadic, but foodborne botulism outbreaks are reported each year. Food-borne botulism cases are most often associated with home-canned foods. Other food vehicles identified in outbreak investigations have included fermented or salted seafood, potatoes baked in aluminum foil, garlic in oil, onions held under butter, and homemade salsa (61). Most seafood-associated cases are caused by toxin type E, which is associated most SEAFOOD-ASSOCIATED INFECTIONS 401 commonly with eating traditional Alaska Native foods, such as fermented salmon heads, salmon eggs, and blubber and skin from marine animals (muktuk) (14). C. botulinum type E spores are commonly found in fish and aquatic animals, and implicated seafood has been fermented under anaerobic conditions that favor the germination of C. botulinum (43, 66). Measures to prevent seafood-borne botulism have included educational efforts to promote proper methods to ferment foods and to boil fermented foods before consumption, especially if they were stored in tightly sealed plastic or glass containers (10). Other toxin-forming bacteria. Staphylococcus aureus, Clostridium perfringens, and Bacillus cereus can form enterotoxins that cause acute gastrointestinal illness. The illness typically seen with S. aureus and B. cereus intoxication is the onset of nausea, vomiting, and mild diarrhea within 1 to 6 h after ingestion of contaminated food. Incubation periods are very short because preformed toxin is present in the ingested food. Intoxication with C. perfringens has a slightly longer incubation period, because toxin is not preformed but is produced in the gastrointestinal tract. Symptoms include watery diarrhea and abdominal cramps starting 8 to 16 h after ingestion of contaminated food. Duration of symptoms is usually less than 24 h; therefore, many cases likely go undiagnosed. Diagnosis is confirmed by isolation of the organism in samples of stool, vomitus, or food. Additionally, S. aureus enterotoxin can be detected in food samples, which can be useful in situations in which the organism has been killed in food processing or preparation and therefore cannot be cultured. Only certain strains of S. aureus produce a toxin that causes gastrointestinal illness. The main reservoir is humans, who carry the bacterium in their nasal passages, skin, or wounds. S. aureus contamination of food, including seafood, is usually due to contamination by a food worker during food preparation (7, 65). B. cereus and C. perfringens are found in the soil and are ubiquitous. Only a few reports of illness due to the presence of these organisms in seafood have been published, but the mechanisms in these cases appear to be similar to those for other foods (7). To prevent outbreaks of toxin-mediated illnesses, it is important to keep foods refrigerated and to ensure proper cooling of hot foods to refrigerator temperatures. Outbreaks are usually associated with foods left at inappropriate temperatures for prolonged periods, allowing multiplication of the organism and enterotoxin production (7, 51). Viruses Norovirus. Norovirus is a small structured RNA virus that is among the caliciviruses recognized as human pathogens. Norovirus infection causes a self-limited illness characterized by diarrhea, vomiting, nausea, abdominal cramps, and sometimes headache, myalgias, and low-grade fever. The virus may be identified by electron microscopy or reverse transcriptase PCR of stool samples and by enzyme immunoassay for detection of viral antigen in serum samples. Humans are the only known reservoir, and norovirus is transmitted by person-to-person spread through the fecal-oral route or through contaminated food or water. The infectious dose is low, and attack rates are high. Noroviruses can persist in the environment and can infect large numbers of people of all ages. Most outbreaks are re- 402 IWAMOTO ET AL. CLIN. MICROBIOL. REV. ported from child care centers, cruise ships, long-term care facilities, and other closed populations. Norovirus is a leading cause of food-borne illness and outbreaks (44, 68), although the number of reported outbreaks is likely grossly underestimated because of a lack of routine availability or use of diagnostic testing. The adoption of reverse transcriptase PCR by the CDC and state public health laboratories in the 1990s has greatly improved and increased the identification of norovirus as the etiologic agent of food-borne outbreaks (68). Seafood harvested from sewage-contaminated waters has caused outbreaks of norovirus gastroenteritis. Large outbreaks have been associated with consumption of raw or inadequately cooked shellfish, such as a series of oyster- and clam-associated outbreaks in which northeastern coastal waters were implicated (46). Shellfish, particularly bivalve mollusks that are filter feeders, can accumulate large numbers of viruses. Contamination of harvest areas with human sewage, which has occurred following overboard sewage dumping by oyster harvest boats and from sewage runoff into harvest areas following heavy rains, has been an important source of outbreaks. Additionally, insufficient cooking, such as steaming clams only until they open rather than to higher temperatures that kill noroviruses, has contributed to illness and outbreaks (23, 46). Control measures have focused on monitoring harvest waters for fecal coliforms and encouraging adequate cooking of seafood; however, continued outbreaks of illness have brought renewed attention to the risks associated with oyster consumption (36, 41, 46). Hepatitis A virus. Hepatitis A virus is an RNA virus that is classified as a picornavirus. Although clinical manifestations vary in severity, hepatitis A virus infection is the most serious viral infection associated with seafood consumption. Most commonly, it is an acute, self-limited illness associated with fever, malaise, jaundice, anorexia, and nausea; symptoms may last from several weeks to several months. However, deaths from fulminant hepatitis can occur. Severity increases with age, and in rare cases, a prolonged, relapsing hepatitis can occur. In infants and young children, infection is often asymptomatic. Diagnosis is made using serologic tests that measure immunoglobulin M antibody against hepatitis A virus. The illness’s long incubation period (2 to 8 weeks) can make the identification of the source of infection difficult, and hepatitis A virus infection associated with seafood is likely underreported. Sporadic and epidemic cases occur worldwide. In the United States, since the implementation of routine hepatitis A vaccination of children, rates of reported illnesses, especially among children, have declined considerably (67). Humans are the only reservoir of hepatitis A virus, and transmission is generally by the fecal-oral route. Commonsource food-borne outbreaks occur, and outbreaks of hepatitis A virus infections associated with oysters and clams have been described in the United States since the 1960s (22, 40, 55). The infectious dose is thought to be low, and the virus is taken up by the mollusk during feeding. Hepatitis A virus is heat resistant and able to withstand steaming, and appropriate cooking of seafood lessens the chance of ingesting live hepatitis A virus. But because shellfish is commonly prepared in ways that are insufficient to inactivate the virus, many prevention strategies are aimed at controlling contamination prior to food preparation. Contamination most commonly occurs when shellfish growing areas are contaminated with human sewage (22, 55). The largest reported outbreak occurred in China in 1988; almost 300,000 persons were infected after consuming clams harvested from a sewage-contaminated area (56). Fewer outbreaks of hepatitis A virus infection associated with seafood consumption have been reported in the United States in the past 2 decades, which may be attributable, at least in part, to implementation of increased control measures to prevent fecal contamination of harvest beds during the 1980s. This decrease suggests that control strategies may have been effective in reducing the risk of infection via seafood. Recently, the availability of molecular sequencing methods to enhance epidemiologic data has been critical in linking dispersed cases in multiple states to contaminated food products (3). Increases in public health laboratory capacities for molecular sequencing will improve our ability to identify outbreaks of hepatitis A virus infections. Parasites Helminths. Helminths are large, worm-like parasites. Helminthic infections associated with the consumption of raw seafood include infections caused by nematodes, trematodes, and cestodes, notably eustrongyloides, species of Diphyllobothrium (58), and members of the family Anisakidae (59, 69). Clinical manifestations associated with helminthic infections range from no symptoms to mild, chronic gastrointestinal symptoms, allergic reactions, and, rarely, intestinal perforation and invasive disease. Diagnosis of most parasitic infections is confirmed by detection of ova or segments of worms in stool samples. Many worms are present naturally in marine and fresh waters, and most marine animals are infected. Despite the high prevalence of helminths in seafood, however, outbreaks associated with seafood are rarely reported. This observation is likely due to several factors: first, helminths are not able to multiply in food; second, long incubation periods make identification of the source of infection difficult; and third, infections are likely underdiagnosed and underreported, due in part to a lack of routine diagnostic tests (51, 59). Nonetheless, the potential for helminthic infection exists with the consumption of raw seafood. Helminths are killed by adequate freezing and by cooking. Control strategies for industry to reduce the risk of helminthic infections also include visually inspecting fish, by means such as candling, for parasites that are large enough to be detected visually. Protozoa. Protozoa are an uncommon cause of food-borne illnesses in the United States, and common-source outbreaks are almost always waterborne (44, 70). Protozoa causing recognized seafood-associated illnesses have included Giardia spp. (54). Giardia is one of the most commonly identified intestinal parasites in the United States. Clinical manifestations may include abdominal pain, flatulence, anorexia, and a protracted course of watery, malodorous diarrhea; asymptomatic infection is common. Laboratory diagnosis is most often made by identification of trophozoites or cysts in stool specimens or by detection of stool antigens by enzyme immunoassay. Humans and other animals are the reservoir of infection. Food-borne outbreaks of giardiasis have been reported in which transmission occurred through contamination of food by infected food handlers (54). Protozoa are sensitive to heat and References 22, 40, and 55 VOL. 23, 2010 SEAFOOD-ASSOCIATED INFECTIONS to prolonged freezing (8). Strategies to prevent food-borne transmission include adequate cooking and preventing contamination of food during preparation. EPIDEMIOLOGY OF SEAFOODASSOCIATED INFECTIONS Sources of Data and Methods We examined two data sources to understand the epidemiology of seafood-associated illnesses in the United States: the Food-Borne Disease Outbreak Surveillance System and the Cholera and Other Vibrio Illness Surveillance System (COVIS). Determining the food that caused an individual illness is difficult, except during investigations of outbreaks or of certain infections which are almost always associated with a specific type of food. Investigations of outbreaks of food-borne illnesses are used to determine the food vehicles for pathogens that cause illness and to improve our understanding of the epidemiology of these outbreaks. State and local health departments identify and investigate food-borne outbreaks and, in turn, report these outbreaks to the CDC. Since the early 1970s, the CDC has collected reports from all states and territories on recognized food-borne disease outbreaks, defined as 2 or more cases of a similar illness resulting from ingestion of a common food (53). Information reported includes the number of persons affected, the etiologic agent identified, characteristics of illnesses, the month of illness onset, the implicated food item, possible sources of contamination, and other contributing factors. These surveillance data have been maintained in a central, electronic database since 1973. In 1998, the reporting procedures were modified to provide feedback to reporting states, and the CDC began verifying outbreak reports with states on a yearly basis. For this analysis, we included outbreaks with an implicated seafood vehicle and a single confirmed infectious etiologic agent. Seafood vehicles were categorized into the following three commodity groups: (i) mollusks (e.g., oysters, clams, and scallops); (ii) crustaceans (e.g., shrimp, crab, and lobster); and (iii) finfish (e.g., salmon, tuna, and finfish eggs) and other aquatic vertebrates (e.g., whale and seal), or “fish” for brevity. Outbreaks caused by multiple etiologic agents and outbreaks for which implicated foods could not be classified into the single overarching food commodity class “seafood” were not included in this analysis, unless a single seafood was identified as the contaminated ingredient responsible for the outbreak. Additionally, we examined surveillance case reports of Vibrio illnesses reported through COVIS, which is a collaborative effort of state and county health departments, the FDA, and the CDC. For the investigation of cases of vibriosis, a standard report form is used to collect detailed information on the Vibrio species causing illness; demographic information, medical history, and travel and food history of the patient; and shellfish traceback information, when available. COVIS data are used to help define Vibrio-related syndromes, describe the epidemiology of vibriosis, and identify vehicles of infection. Surveillance for vibriosis began in 1988 in Gulf Coast states and subsequently expanded nationally. In January 2007, vibriosis became a nationally notifiable disease (16). 403 Summary of Seafood-Associated Outbreaks and Infections General epidemiologic characteristics. During 1973 to 2006, 188 outbreaks of seafood-associated infections, causing 4,020 illnesses, 161 hospitalizations, and 11 deaths, were reported to the Food-Borne Disease Outbreak Surveillance System. Most of these seafood-associated outbreaks (143 [76.1%]) were due to a bacterial agent; 40 (21.3%) outbreaks had a viral etiology, and 5 (2.6%) had a parasitic cause (Table 1). The number of confirmed outbreaks reported increased greatly during 1998, when enhanced surveillance of food-borne outbreaks began (Fig. 1). Otherwise, the number of outbreaks fluctuated from year to year during the study period, with no significant increasing or decreasing trends seen. Outbreaks ranged in size from 2 to 400 affected persons, with an overall median outbreak size of 5 persons affected. The median size of outbreaks was stable through the 1970s and 1980s. Starting in the early 1990s, the median outbreak size varied substantially, with large peaks seen during 1993, 1995, and 2004. Seafood-associated outbreaks occurred throughout the year, with a peak during late summer (Fig. 2). However, seasonality differed by etiology. Bacterial pathogens, especially vibrios, caused more outbreaks during warmer months, whereas outbreaks of seafood-associated norovirus infections occurred more frequently during colder months. Seafood-associated outbreaks from all causes were reported most commonly from the following coastal states (Fig. 3): Alaska (39), New York (19), California (17), Florida (16), Oregon (11), and Washington (16). All other states reported fewer than 10 outbreaks during the study period. Etiologic agents and implicated seafood vehicles varied by state. Almost all outbreaks reported from Alaska, which reported 39 (20.7%) outbreaks, were due to botulism. States in the Pacific Northwest reported a disproportionate number of Vibrio and norovirus outbreaks, largely associated with molluscan shellfish (11, 12). Notably, in recent years, outbreaks of infections due to some pathogens usually associated with seafood harvested from warm waters were reported from more northerly areas of the country that had not previously reported outbreaks. For example, the first outbreak of Vibrio parahaemolyticus infections in Alaska was reported in 2004, during a period when waters in the area experienced historically high temperatures (42). Nine multistate seafoodassociated outbreaks were reported to the CDC, and almost all of these outbreaks occurred after the mid-1990s. Each of these multistate outbreaks was associated with oysters that were widely distributed. Seafood-associated outbreaks of infection varied by seafood commodity. Mollusks were implicated in 85 (45.2%) outbreaks, followed by fish in 73 (38.8%) outbreaks and crustaceans in 30 (16.0%) outbreaks (Table 1). All of the molluskassociated outbreaks were associated with bivalve mollusks, including oysters (implicated in 72 outbreaks) and clams (11 outbreaks.) In fish-associated outbreaks, the most commonly implicated fish was salmon (15 outbreaks); “salmon” included fermented fish parts and fermented salmon eggs, which accounted for 10 of these outbreaks. Other commonly reported fish vehicles were tuna (10 outbreaks), seal meat (9 outbreaks), whale (7 outbreaks), and whitefish (not further specified) (4 outbreaks). Among crustacean-associated outbreaks, the most commonly implicated items were crab (15 outbreaks) and 1 (1) 1 (1) 0 (0) 1 (1) 3 (4) 73 (100) Parasites Anisakidae Giardia lamblia Paragonimus Diphyllobothrium Total Total (1973–2006) 1,210 (100) 14 (1) 29 (2) 0 (0) 10 (1) 53 (4) 418 (35) 7 (1) 425 (35) 0 (0) 0 (0) 261 (22) 259 (21) 7 (1) 0 (0) 0 (0) 0 (0) 0 (0) 0 (0) 732 (60) 0 (0) 0 (0) 10 (14) 6 (8) 3 (4) 0 (0) 0 (0) 0 (0) 0 (0) 0 (0) 65 (89) 4 (5) 1 (1) 5 (7) 7 (1) 0 (0) 152 (13) 46 (4) 0 (0) 93 (100) 0 (0) 0 (0) 0 (0) 0 (0) 0 (0) 0 (0) 0 (0) 0 (0) 0 (0) 0 (0) 15 (16) 17 (18) 0 (0) 0 (0) 0 (0) 0 (0) 0 (0) 0 (0) 93 (100) 0 (0) 0 (0) 61 (66) 0 (0) 0 (0) No. (%) of No. (%) of illnesses hospitalizations Fish 2 (3) 0 (0) 43 (59) 1 (1) 0 (0) No. (%) of outbreaks Viruses Norovirus Hepatitis A virus Total Bacteria Bacillus cereus Campylobacter spp. Clostridium botulinum Clostridium perfringens Escherichia coli, enteroaggregative E. coli, enterohemorrhagic Listeria monocytogenes Salmonella Shigella spp. Staphylococcus aureus Vibrio cholerae, toxigenic Vibrio cholerae, nontoxigenic Vibrio parahaemolyticus Vibrio vulnificus Vibrio spp., not specified Total Etiology 30 (100) 0 (0) 0 (0) 1 (0) 0 (0) 1 (0) 0 (0) 1 (3) 1 (3) 1 (3) 1 (3) 4 (13) 1 (3) 2 (7) 3 (10) 0 (0) 12 (40) 0 (0) 0 (0) 28 (93) 2 (7) 0 (0) 0 (0) 1 (3) 1 (3) No. (%) of outbreaks 609 (100) 0 (0) 0 (0) 18 (0) 0 (0) 18 (0) 0 (0) 7 (1) 7 (1) 21 (3) 2 (0) 81 (13) 25 (4) 22 (4) 10 (2) 0 (0) 234 (38) 0 (0) 0 (0) 584 (96) 122 (20) 0 (0) 0 (0) 55 (9) 12 (2) No. (%) of illnesses Crustaceans 13 (100) 0 (0) 0 (0) 2 (0) 0 (0) 2 (0) 0 (0) 0 (0) 0 (0) 0 (0) 1 (8) 8 (62) 0 (0) 0 (0) 1 (8) 0 (0) 1 (8) 0 (0) 0 (0) 11 (85) 0 (0) 0 (0) 0 (0) 0 (0) 0 (0) No. (%) of hospitalizations 85 (100) 0 (0) 1 (1) 0 (0) 0 (0) 1 (1) 27 (32) 7 (8) 34 (40) 0 (0) 0 (0) 4 (5) 5 (6) 0 (0) 0 (0) 4 (5) 33 (39) 1 (1) 1 (1) 50 (59) 0 (0) 2 (2) 0 (0) 0 (0) 0 (0) No. (%) of outbreaks 2,201 (100) 0 (0) 3 (0) 0 (0) 0 (0) 3 (0) 747 (34) 121 (6) 868 (39) 0 (0) 0 (0) 32 (1) 118 (5) 0 (0) 0 (0) 12 (1) 1,159 (53) 2 (0) 2 (0) 1,330 (60) 0 (0) 5 (0) 0 (0) 0 (0) 0 (0) No. (%) of illnesses Mollusks 55 (100) 0 (0) 0 (0) 0 (0) 0 (0) 0 (0) 16 (29) 7 (13) 23 (42) 0 (0) 0 (0) 5 (9) 3 (5) 0 (0) 0 (0) 0 (0) 23 (42) 1 (2) 0 (0) 32 (58) 0 (0) 0 (0) 0 (0) 0 (0) 0 (0) No. (%) of hospitalizations TABLE 1. Seafood-associated outbreaks of infection, by etiology and seafood commodity, 1973 to 2006 188 (100) 1 (1) 2 (1) 1 (0) 1 (1) 5 (3) 31 (16) 9 (5) 40 (21) 1 (1) 1 (1) 18 (10) 12 (6) 5 (3) 3 (2) 4 (2) 45 (24) 1 (1) 1 (1) 143 (76) 4 (2) 2 (1) 43 (23) 2 (1) 1 (1) No. (%) of outbreaks 4,020 (100) 14 (0) 32 (1) 18 (0) 10 (1) 74 (2) 1,165 (29) 135 (3) 1,300 (32) 21 (1) 2 (0) 374 (9) 402 (10) 29 (1) 10 (0) 12 (0) 1,393 (35) 2 (0) 2 (0) 2,646 (66) 129 (3) 5 (0) 152 (4) 101 (3) 12 (0) No. (%) of illnesses All seafood 161 (100) 0 (0) 0 (0) 2 (0) 0 (0) 2 (1) 16 (10) 7 (4) 23 (14) 0 (0) 1 (1) 28 (17) 20 (12) 0 (0) 1 (1) 0 (0) 24 (15) 1 (1) 0 (0) 136 (84) 0 (0) 0 (0) 61 (38) 0 (0) 0 (0) No. (%) of hospitalizations 404 IWAMOTO ET AL. CLIN. MICROBIOL. REV. VOL. 23, 2010 SEAFOOD-ASSOCIATED INFECTIONS 405 FIG. 1. Number of confirmed seafood-associated outbreaks and outbreak-related cases, by year and etiology, 1973 to 2006. shrimp (15 outbreaks). Comparing seafood categories within different periods, the number and proportion of mollusk-associated outbreaks increased greatly during the study period, from 10% of outbreaks during 1973 to 1979 to 56.6% of outbreaks during 1998 to 2006 (Fig. 4). The proportion of outbreaks due to fish decreased during the study period, from 90.0% of outbreaks to 24.2% of outbreaks during the last part of the study period. The proportion due to crustaceans varied, ranging from no outbreaks during the first decade to 19.2% of outbreaks. Outbreaks and infections caused by bacteria. Bacteria were reported as the etiologic agent in 143 (76.1%) outbreaks, caus- FIG. 2. Number of confirmed seafood-associated outbreaks, by etiology and month of occurrence, 1973 to 2006. 406 IWAMOTO ET AL. CLIN. MICROBIOL. REV. FIG. 3. Number of confirmed seafood-associated outbreaks in the United States, by state, 1973 to 2006. ing 2,646 illnesses, 136 hospitalizations, and 11 deaths. The median size of seafood-associated outbreaks caused by bacteria was 4 cases, with a range of 2 to 400 cases. Almost all outbreaks associated with fish (89.0%) and crustaceans (93.3%) were caused by a bacterial agent; among outbreaks associated with mollusks, 50 outbreaks (58.8%) were caused by a bacterium. Vibrios were the most commonly reported cause of seafood- FIG. 4. Percentages of seafood-associated outbreaks of infection attributable to seafood commodities in four multiyear ranges. VOL. 23, 2010 SEAFOOD-ASSOCIATED INFECTIONS 407 FIG. 5. Numbers of outbreaks and sporadic cases of Vibrio infection, by species and year, 1997 to 2006. associated outbreaks. Specifically, Vibrio parahaemolyticus caused more outbreaks and illnesses than any other pathogen (45 outbreaks [23.9% of all infectious disease outbreaks], 1,393 illnesses, and no deaths) during the study period. Other Vibrio species reported included toxigenic V. cholerae (3 outbreaks, 10 illnesses, and no deaths), non-O1, non-O139 V. cholerae (4 outbreaks, 12 illnesses, and no deaths), and V. vulnificus (1 outbreak, 2 illnesses, and 1 death). Among outbreaks of Vibrio illness, 15 (27.8%) were associated with crustaceans, and the remaining 39 (72.2%) were associated with mollusks, particularly oysters. Outbreaks of Vibrio illnesses were sharply seasonal, with 44 (81.5%) occurring during the warmer months of May to September. The number of reported outbreaks of Vibrio infections increased over the study period, with the greatest number reported during the last decade, 1997 to 2006. The largest reported seafood-associated outbreak was an outbreak in 1998 of V. parahaemolyticus infections associated with oyster consumption, causing 416 illnesses among persons in 13 states (19). During 1997 to 2006, there was substantial yearto-year variability in the number of outbreaks of Vibrio infections, with large multistate outbreaks associated with oysters occurring during 1998 and 2006 (12, 19). During the past decade, the increases in the number and size of Vibrio outbreaks mirrored the trends in reports of sporadic cases of infections nationally, as reported to COVIS (Fig. 5). During 1997 to 2006, 4,755 cases of Vibrio illness were reported to COVIS; of these, 3,406 (71.6%) were classified as foodborne infections. The most commonly reported Vibrio species causing food-borne infections were V. parahaemolyticus (1,931 [56.7%] food-borne Vibrio infections) and V. vulnificus (459 [13.5%] infections). V. parahaemolyticus infections were most often food borne (89.0% [1,931/2,170 infections]). Among patients with food-borne V. parahaemolyticus infections who reported food exposures, almost all (94.5%) patients reported eating seafood during the week before illness onset, most commonly oysters (72.5% [1,143/1,577 patients]). Larger numbers of sporadic cases of Vibrio infection were reported in years during which multistate outbreaks were also reported. During these years, warmer sea temperatures were documented (12, 18, 42). Similarly, the distribution of sporadic cases was sharply seasonal, with most cases (72.8%) occurring during summer months, corresponding to warmer water temperatures. Of the 944 V. vulnificus cases, 459 (47.0%) were classified as foodborne infections; among patients with food-borne V. vulnificus infection who reported food exposures, 91.1% reported seafood consumption during the week before illness, most commonly oysters (80.5% [289/361 patients]). Nearly all patients (92.2%) with food-borne V. vulnificus infection were reported to have a preexisting medical condition, most commonly liver disease. The case fatality rate for food-borne V. vulnificus infections was 48.3%. During the study period, the second most commonly reported bacterial pathogen causing seafood-associated outbreaks was Clostridium botulinum, which caused 43 outbreaks, 152 illnesses, 61 hospitalizations, and 9 deaths. Most (86.0% [37/43 reports]) reports came from Alaska. Most of these outbreaks occurred among Alaska Natives and were associated with the consumption of traditional Alaska Native seafood dishes, which are often fermented under anaerobic conditions where botulinum spores may germinate (66). Botulinum toxin type E was most frequently identified in these seafood-associated outbreaks of botulism. Seafood associated with the outbreaks included fish, particularly salmon eggs and fish heads, seal, and whale meat (43). No botulism outbreaks were associated with consumption of mollusks or crustaceans. Other bacterial etiologies of seafood-associated outbreaks included Salmonella, which caused 18 outbreaks, 374 illnesses, and 28 hospitalizations. Fish were implicated in 10 outbreaks; specifically, gefilte fish, a traditional dish made from ground deboned fish, was implicated in 4 outbreaks, with whitefish implicated in 2 outbreaks, bass in 1 outbreak, and unspecified fish in the rest (3). Mollusks and crustaceans were each impli- 408 IWAMOTO ET AL. cated in 4 outbreaks. Most outbreaks of Salmonella infection occurred during warmer months. Shigella was the etiologic agent in 12 outbreaks, causing 402 illnesses and 20 hospitalizations. Implicated seafood included fish in 6 outbreaks, raw oysters in 4 outbreaks, scallops in 1 outbreak, and crab in 1 outbreak. Outbreaks caused by viruses. During the study period, 40 (21.3%) seafood-associated outbreaks were caused by viruses. Seafood associated with these outbreaks included mollusks (34 outbreaks [85.0% of outbreaks caused by viruses]), fish (5 outbreaks [12.5%]), and crustaceans (1 outbreak [2.5%]). The median size of viral outbreaks was 10 cases (range, 2 to 380 cases). Overall, norovirus was the third most commonly reported pathogen associated with seafood and the most common viral agent, causing 31 (77.5%) outbreaks of viral illness. Mollusk-associated, especially raw oyster-associated, outbreaks of norovirus were common (27 outbreaks) and made up almost one-third (31.8% [27/85 outbreaks]) of all molluscan outbreaks. Unlike outbreaks of bacterial illness, outbreaks of norovirus illness were more common during cooler months, with more than three-fourths (77.4%) of outbreaks occurring during October to March. Confirmed outbreaks of norovirus infection were reported more commonly during the past decade; 26 of 31 (83.8%) outbreaks were reported during 1998 to 2006. However, the etiology of outbreaks changed over the course of the study period. During the early 1980s, large outbreaks of viral gastroenteritis caused by molluscan shellfish (46) were prominent. These were followed by a decrease in reported outbreaks of viral illness that lasted until 2000, when reports again increased, likely due to better diagnostic testing, an improved ability to confirm etiology, and improved public health surveillance for outbreaks. Hepatitis A virus was the cause of 9 seafood-associated outbreaks. Most outbreaks of hepatitis A virus infection (7 outbreaks [77.7%]) were associated with mollusks. Tuna and crab were each implicated in one outbreak. Most outbreaks occurred during the 1980s (22, 46), none were reported during the 1990s, and only 2 were reported after 2000 (3). Outbreaks caused by parasites. Seafood-associated outbreaks caused by parasites were rare, with 5 outbreaks reported during the study period. Outbreaks ranged in size from 3 to 29 persons affected; the median size of outbreaks was 14 cases. Reported outbreaks included 2 outbreaks of giardiasis, one caused by salmon (54) and one by oysters, an outbreak of Paragonimus infections associated with the consumption of live crabs (15), an outbreak of Diphyllobothrium infection associated with salmon consumption (9, 58), and an outbreak of anisakiasis associated with consumption of an unspecified fish. DISCUSSION We have described the epidemiology of infections associated with seafood consumption in the United States from 1973 to 2006. Seafood—finfish, marine mammals, mollusks, and crustaceans—is an important cause of food-borne illness and outbreaks in the United States. Our analysis identified specific seafood vehicles frequently associated with illness. This information can help to guide future prevention efforts. Seafoodassociated outbreaks of infection were most often attributed to consumption of molluscan shellfish, particularly raw oysters, 78% Main Outbreak is Shellfish CLIN. MICROBIOL. REV. and most often caused Vibrio illnesses and norovirus infections. Over the study period, both the absolute number of outbreaks and the proportion of outbreaks caused by molluscan shellfish increased. Botulism cases associated with fish were also reported frequently, although these outbreaks were reported almost exclusively from Alaska. Etiologies and implicated seafood commodities changed over time during the study period. The cause of these changes is likely multifactorial: enhanced food-borne outbreak surveillance began in the late 1990s; laboratory diagnostic capacities have improved, particularly for norovirus but also for other pathogens, resulting in better detection of outbreaks; control efforts, especially in shellfish sanitation, have evolved; and changes in environmental factors may favor the occurrence of some pathogens. Our analysis of surveillance data is subject to several limitations. The true burden of illnesses associated with seafood consumption is probably much greater than what we report. Our understanding of foods and pathogens responsible for illness is largely derived from information gained from outbreak investigations. However, many outbreaks likely go unrecognized and uninvestigated. Moreover, the Food-Borne Disease Outbreak Surveillance System is a passive system that relies on voluntary reporting, which may lead to further underestimation of the actual number of outbreaks and illnesses that occur. Outbreak reporting may not be uniform across states, which may be due in part to whether states have dedicated food-borne disease epidemiologists. Also, outbreaks comprise only a small proportion of all cases of food-borne illness. No information is available on seafood-borne transmission in sporadic cases of infection other than Vibrio illnesses. Enhanced surveillance for food-borne outbreaks began in 1998. As a result, an abrupt increase in reported outbreaks occurred, which should not be interpreted as a true increase in the number of outbreaks. Also, improved laboratory methods and surveillance increased the ability to detect and investigate outbreaks during the study period. For example, subtype-based laboratory surveillance has improved the ability to detect outbreaks of infections associated with seafood items that are widely distributed, as in multistate outbreaks, and with pathogens with long incubation periods, such as hepatitis A virus. Other laboratory methods that evolved during the past decade include testing for the presence of norovirus by PCR and increased use of appropriate selective media to detect Vibrio organisms in stool. Contamination of seafood can occur before harvest or at any point from harvest through final preparation. The types and numbers of pathogens present in seafood are affected by the environment from which the seafood was harvested and by sanitation during subsequent handling, processing, storage, transportation, and final preparation. Survival of food-borne pathogens is more likely to occur in foods that are consumed undercooked or raw and in those that experience time and temperature abuse, such as may occur during delays between harvest and refrigeration. Control strategies to prevent seafood-associated illnesses include monitoring harvest waters, identification and implementation of process controls, and consumer education. Federal agencies, state governments, and private industry all bear responsibility for reducing seafood-associated infections. The FDA plays an important role in establishing guidelines and VOL. 23, 2010 SEAFOOD-ASSOCIATED INFECTIONS providing oversight to ensure safer fish and fishery products. Prevention strategies developed by the FDA and the seafood industry to minimize the risk of microbial contamination and decrease the risk of seafood-associated infection include good manufacturing practices, which address sanitation conditions and practices, and a seafood hazard analysis and critical control point (HACCP) program. The purpose of a HACCP is to identify sources and points in processes at which the risk of contamination is high, from harvest to consumption, so that processes to decrease these risks can be implemented and monitored. During the mid-1990s, the FDA issued regulations for the seafood industry, relying on HACCP-based principles. Every seafood harvester and processor is now required to use a HACCP-based system. Examples of HACCP-based principles include candling of fish to detect parasites, a low-acid canning program for canned tuna and salmon to prevent botulism, and rapid chilling of fish after death to prevent scombrotoxin formation (24). Shellfish regulation has a distinctive history. Control strategies in addition to those mentioned above and specifically aimed at promoting the safety of molluscan shellfish are implemented through the National Shellfish Sanitation Program (NSSP). The NSSP guidelines are uniform shellfish safety standards that regulate the harvesting, processing, and shipping of shellfish for interstate commerce. The NSSP was established in response to large outbreaks of typhoid fever associated with contaminated mollusks that occurred in the 1920s. Through the ensuing decades, NSSP guidelines have evolved to address public health problems. Since 1985, NSSP guidelines have been established through the Interstate Shellfish Sanitation Conference (ISSC), which is a cooperative organization with representation from the FDA and other federal agencies, state health departments and shellfish authorities, and private industry. Commercial shellfish harvesting is regulated by states in accordance with NSSP guidelines. The standards for harvesting shellfish are established by state rules and regulations, and harvesting occurs in designated approved areas. Under the NSSP, standards for harvesting shellfish involve monitoring of environmental factors, including coliform counts, marine biotoxins, levels of V. parahaemolyticus in sampled oysters, water salinity levels, and ambient and water temperatures. Fecal coliforms are used as an indicator of bacterial contamination and to classify shellfish harvesting areas as safe or unsafe. While they have been useful as an indicator of the presence of feces-related bacteria in harvest beds, they are less reliable for naturally occurring pathogens (e.g., Vibrio species) and for enteric viruses. Our surveillance data suggest that the greatest current seafood safety risks involve bivalve mollusks contaminated with naturally occurring pathogens. Therefore, prevention of initial contamination at or before the time of harvest is important, and environmental monitoring is critical. Investigation of seafood-associated outbreaks and traceback information on shellfish implicated in sporadic cases of Vibrio illness have indicated that illness is often associated with consumption of shellfish harvested from warmer waters (18, 19, 27, 42, 60). The recent investigation of an outbreak of V. parahaemolyticus infections associated with Alaskan oysters underscores the need to examine the emerging health risks posed by changing environmental factors, such as rising water temperatures (42). In an effort to further reduce the risk of shellfish- 409 associated Vibrio illnesses, the ISSC has established additional control measures based on environmental conditions such as air and water temperature (26). Additional control measures exist to prevent contamination during postharvest handling, processing, and distribution of shellfish. Bacterial proliferation and toxin formation can occur if contaminated seafood is not maintained at appropriate temperatures; therefore, minimizing the time between harvest and refrigeration is critical, especially during summer months (27). The FDA and ISSC have established NSSP guidelines for storage times and temperatures for specific seafood products. However, the potential benefits of implementing strict requirements to shorten the time between shellfish harvest and refrigeration are countered by concerns for the potential economic burden to the shellfish industry. A unique control strategy for molluscan shellfish is the labeling of all containers containing bivalve mollusks with tags containing information about the harvest site and date. These tags are maintained by harvesters, dealers, shippers, and restaurants for at least 90 days after sale. This information on the location of harvesting facilitates traceback to harvest waters of lots associated with illness. It is important that industry-implemented postharvest processing methods for seafood, particularly oysters, are available to reduce microbial hazards. Established and well-accepted methods include individually quick-freezing oysters, pasteurization, irradiation, and high hydrostatic pressure, and new methods continue to be developed. These processing techniques reduce microorganisms to nondetectable levels and reduce the risk of illness (27). Consumers should be aware of the potential health risks associated with eating seafood. Seafood-borne infections can be prevented by cooking seafood thoroughly, storing foods properly, and avoiding cross-contamination after cooking. However, some seafood is commonly consumed raw or minimally cooked. Persons with underlying medical conditions such as liver disease, diabetes, or immunosuppressing conditions are at higher risk of acquiring severe infection and should be especially careful. Educational strategies have focused particularly on those persons. Messages warning consumers of the potential risks of infection associated with raw oyster consumption are posted in restaurants in states where illnesses caused by Vibrio vulnificus are prevalent; however, cases continue to occur, suggesting that these educational strategies by themselves may not prevent all cases (47) and that additional regulatory measures, as well as more effective consumer education, may be needed to further reduce the incidence of illness. For clinicians and laboratorians, prompt recognition of infection in patients who seek medical attention for illness after eating raw or undercooked seafood is important for appropriate testing (e.g., use of TCBS agar for culture of stool samples) and early treatment, as necessary. Rapid reporting of these cases to public health authorities is critical to identify both contaminated seafood and risky harvest areas in order to implement timely control measures. Seafood is part of a healthful diet, but seafood consumption is not risk-free. Multiple outbreaks of seafood-associated infections, especially mollusk-associated outbreaks of Vibrio infections, continue to occur every year in the United States, suggesting that existing control strategies have not been optimally effective. Prevention of seafood-associated infections re- Outbreak = More than 2 410 IWAMOTO ET AL. quires an understanding not only of the etiologic agents and seafood commodities associated with illness but also of the mechanisms of contamination that are amenable to control. Defining these problem areas, which relies on surveillance of seafood-associated infections through outbreak and case reporting, can lead to targeted research and help to guide control efforts. Coordinated efforts are necessary to further reduce the risk of seafood-associated illnesses. Continued surveillance will be important to assess the effectiveness of current and future prevention strategies. REFERENCES 1. Abbott, S. L., J. M. Janda, J. A. Johnson, and J. J. Farmer. 2007. Vibrio and related organisms, 9th ed. ASM Press, Washington, DC. 2. Ayers, T., M. Iwamoto, D. L. Swerdlow, and I. Williams. 2008. Epidemiology of seafood-associated outbreaks in the United States, 1973–2006, abstr. P370. Abstr. Int. Assoc. Food Prot. Annu. Meeting, Columbus, OH. 3. Bialek, S. R., P. A. George, G. L. Xia, M. B. Glatzer, M. L. Motes, J. E. Veazey, R. M. Hammond, T. Jones, Y. C. Shieh, J. Wamnes, G. Vaughan, Y. Khudyakov, and A. E. Fiore. 2007. Use of molecular epidemiology to confirm a multistate outbreak of hepatitis A caused by consumption of oysters. Clin. Infect. Dis. 44:838–840. 4. Blake, P. A., M. H. Merson, R. E. Weaver, D. G. Hollis, and P. C. Heublein. 1979. Disease caused by a marine vibrio: clinical characteristics and epidemiology. N. Engl. J. Med. 300:1–5. 5. Brands, D. A., A. E. Inman, C. P. Gerba, J. Mare, S. J. Billington, L. A. Saif, J. F. Levine, and L. A. Joens. 2005. Prevalence of Salmonella spp. in oysters in the United States. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:893–897. 6. Brenner, F. W., R. G. Villar, F. J. Angulo, R. Tauxe, and B. Swaminathan. 2000. Salmonella nomenclature. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:2465–2467. 7. Bryan, F. L. 1980. Epidemiology of foodborne diseases transmitted by fish, shellfish and marine crustaceans in the United States, 1970–1978. J. Food. Prot. 43:859–876. 8. Casemore, D. P. 1990. Foodborne protozoal infection. Lancet 336:1427– 1432. 9. CDC. 1981. Diphyllobothriasis associated with salmon. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 30:331–338. 10. CDC. 31 July 2000, posting date. Keeping your family safe from botulism. CDC, Atlanta, GA. http://www2.cdc.gov/phtn/botulism/default/default.asp. 11. CDC. 1998. Outbreak of Vibrio parahaemolyticus infections associated with eating raw oysters—Pacific Northwest, 1997. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 47:457–461. 12. CDC. 2006. Vibrio parahaemolyticus infections associated with consumption of raw shellfish—three states, 2006. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 55:854–856. 13. Reference deleted. 14. CDC. 9 January 2009, posting date. Summary of botulism cases. CDC, Atlanta, GA. http://www.cdc.gov/nationalsurveillance/botulism_surveillance .html. Accessed 2 February 2010. 15. CDPH. 18 August 2006, posting date. Consumers warned against eating raw, imported, freshwater crabs after two restaurant diners suffer from unusual lung infection. California Department of Health Services, Sacramento, CA. http: //www.cdph.ca.gov/pubsforms/Guidelines/Documents/fdb%20Paragonimus% 20Rel.pdf. 16. CSTE. 14 September 2006, posting date. CSTE position statement: national reporting for non-cholera Vibrio infections. CSTE, Atlanta, GA. http://www .cste.org/PS/2006pdfs/PSFINAL2006/06-ID-05FINAL.pdf. 17. Daniels, J. L., M. P. Longnecker, A. S. Rowland, and J. Golding. 2004. Fish intake during pregnancy and early cognitive development of offspring. Epidemiology 15:394–402. 18. Daniels, N. A., L. C. MacKinnon, R. Bishop, S. Altekruse, B. Ray, R. M. Hammond, S. Thompson, S. Wilson, N. H. Bean, P. M. Griffin, and L. Slutsker. 2000. Vibrio parahaemolyticus infections in the United States, 1973– 1998. J. Infect. Dis. 181:1661–1666. 19. Daniels, N. A., B. Ray, A. N. Easton, N. N. Marano, E. Kahn, A. L. McShan, L. Del Rosario, T. Baldwin, M. A. Kingsley, N. D. Puhr, J. G. Wells, and F. J. Angulo. 2000. Emergence of new Vibrio parahaemolyticus serotype in raw oysters: a prevention quandary. JAMA 284:1541–1545. 20. Daviglus, M. L., J. Stamler, A. J. Orencia, A. R. Dyer, K. Liu, P. Greenland, M. K. Walsh, D. Morris, and R. B. Shekelle. 1997. Fish consumption and the 30-year risk of fatal myocardial infarction. N. Engl. J. Med. 336:1046–1053. 21. Dechet, A. M., P. A. Yu, N. Koram, and J. Painter. 2008. Nonfoodborne Vibrio infections: an important cause of morbidity and mortality in the United States, 1997–2006. Clin. Infect. Dis. 46:970–976. 22. Desenclos, J. C., K. C. Klontz, M. H. Wilder, O. V. Nainan, H. S. Margolis, and R. A. Gunn. 1991. A multistate outbreak of hepatitis A caused by the consumption of raw oysters. Am. J. Public Health 81:1268–1272. CLIN. MICROBIOL. REV. 23. DuPont, H. L. 1986. Consumption of raw shellfish—is the risk now unacceptable? N. Engl. J. Med. 314:707–708. 24. FDA. 2001. Fish and fisheries products hazards and controls guide, 3rd ed. FDA, Rockville, MD. 25. FDA. 2006, posting date. Fresh and frozen seafood: selecting and serving it safely. FDA, Rockville, MD. http://www.fda.gov/Food/ResourcesForYou /Consumers/ucm077331.htm. 26. FDA. 29 May 2009, posting date. National Shellfish Sanitation Program: guide for the control of molluscan shellfish 2007. FDA, Rockville, MD. http://www.fda.gov/Food/FoodSafety/Product-SpecificInformation/Seafood /FederalStatePrograms/NationalShellfishSanitationProgram/default.htm. Accessed 2 February 2010. 27. FDA. 2005. Quantitative risk assessment on the public health impact of pathogenic Vibrio parahaemolyticus in raw oysters. FDA, College Park, MD. 28. Fewtrell, M. S., R. A. Aboott, K. Kennedey, A. Singhal, R. Morley, E. Caine, C. Jamieson, F. Cockburn, and A. Lucas. 2004. Randomized, double-blind trial of long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation with fish oil and borage oil in preterm infants. J. Pediatr. 144:471–479. 29. Gangarosa, E. J., A. L. Bisno, E. R. Eichner, M. D. Treger, M. Goldfield, W. E. DeWitt, R. Fodor, S. M. Fish, W. J. Dougherty, J. B. Murphy, J. Feldman, and H. Vogel. 1968. Epidemic of febrile gastroenteritis due to Salmonella Java traced to smoked whitefish. Am. J. Public Health 58:114– 121. 30. Heinitz, M. L., R. D. Ruble, D. E. Wagner, and S. R. Tatini. 2000. Incidence of Salmonella in fish and seafood. J. Food Prot. 63:579–592. 31. Helland, I. B., L. Smith, K. Saarem, O. D. Saugstad, and C. A. Drevon. 2003. Maternal supplementation with very-long-chain n-3 fatty acids during pregnancy and lactation augments children’s IQ at 4 years of age. Pediatrics 111:e39–e44. 32. Hibbeln, J. R., J. M. Davis, C. Steer, P. Emmett, I. Rogers, C. Williams, and J. Golding. 2007. Maternal seafood consumption in pregnancy and neurodevelopmental outcomes in childhood (ALSPAC study): an observational cohort study. Lancet 369:578–585. 33. Hlady, W. G., and K. C. Klontz. 1995. The epidemiology of Vibrio infections in Florida, 1981–1993. J. Infect. Dis. 173:1176–1183. 34. Janda, J. M., C. Powers, R. G. Bryant, and S. L. Abbott. 1988. Current perspectives on the epidemiology and pathogenesis of clinically significant Vibrio spp. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1:245–267. 35. Klontz, K. C., S. Lieb, M. Schreiber, H. T. Janowski, L. M. Baldy, and R. A. Gunn. 1988. Syndromes of Vibrio vulnificus infections. Clinical and epidemiologic features in Florida cases, 1981–87. Ann. Intern. Med. 109:318–323. 36. Kohn, M. A., T. A. Farley, T. Ando, M. Curtis, S. A. Wilson, Q. Jin, S. S. Monroe, S. S. Baron, L. M. McFarland, and R. I. Glass. 1995. An outbreak of Norwalk virus gastroenteritis associated with eating raw oysters. Implications for maintaining safe oyster beds. JAMA 273:466–471. 37. Kris-Etherton, P. M., W. S. Harris, and L. J. Appel. 2002. Fish consumption, fish oil, omega-3 fatty acids, and cardiovascular disease: AHA scientific statement. Circulation 106:2747–2757. 38. Kromhout, D., E. B. Bosschieter, and C. de Lezenne Coulander. 1985. The inverse relationship between fish consumption and 20-year mortality from coronary heart disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 312:1205–1209. 39. Levine, W. C., and P. M. Griffin. 1993. Vibrio infections on the Gulf coast: results of first year of regional surveillance. J. Infect. Dis. 167:479–483. 40. Mason, J. O., and W. R. McLean. 1962. Infectious hepatitis traced to the consumption of raw oysters. Am. J. Hygiene 75:90–111. 41. McDonnell, S., K. B. Kirkland, W. G. Hlady, C. Aristeguieta, R. S. Hopkins, S. S. Monroe, and R. I. Glass. 1997. Failure of cooking to prevent shellfishassociated viral gastroenteritis. Arch. Intern. Med. 157:111–116. 42. McLaughlin, J. B., A. DePaola, C. A. Bopp, K. A. Martinek, N. P. Napolilli, C. G. Allison, S. L. Murray, E. C. Thompson, M. M. Bird, and J. P. Middaugh. 2005. Outbreak of Vibrio parahaemolyticus gastroenteritis associated with Alaskan oysters. N. Engl. J. Med. 353:1463–1470. 43. McLaughlin, J. B., J. Sobel, T. Lynn, E. Funk, and J. P. Middaugh. 2004. Botulism type E outbreak associated with eating a beached whale, Alaska. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 10:1685–1687. 44. Mead, P. S., L. Slutsker, V. Dietz, L. F. McCaig, J. S. Bresee, C. Shapiro, P. M. Griffin, and R. V. Tauxe. 1999. Food-related illness and death in the United States. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 5:607–625. 45. Morris, J. G., and R. E. Black. 1985. Cholera and other vibrioses in the United States. N. Engl. J. Med. 312:343–350. 46. Morse, D. L., J. J. Guzewich, J. P. Hanrahan, R. Stricof, M. Shayegani, R. Deibel, J. C. Grabau, N. A. Nowak, J. E. Herrmann, G. Cukor, et al. 1986. Widespread outbreaks of clam- and oyster-associated gastroenteritis. Role of Norwalk virus. N. Engl. J. Med. 314:678–681. 47. Mouzin, E., L. Mascola, M. P. Tormey, and D. E. Dassey. 1997. Prevention of Vibrio vulnificus infections: assessment of regulatory educational strategies. JAMA 278:576–578. 48. Mozaffarian, D., and E. B. Rimm. 2006. Fish intake, contaminants, and human health. JAMA 296:1885–1899. 49. NOAA. 2005. Fisheries of the United States, 2005. National Marine Fisheries Service, Silver Spring, MD. VOL. 23, 2010 50. Oliver, J. D. 2005. Wound infections caused by Vibrio vulnificus and other marine bacteria. Epidemiol. Infect. 133:383–391. 51. Olsen, S. J., J. N. Aucott, and D. L. Swerdlow. 2002. Food poisoning, p. 199–214. In M. Blaser, P. Smith, J. Ravdin, H. Greenberg, and R. Guerrant (ed.), Infections of the gastrointestinal tract, 2nd ed. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA. 52. Olsen, S. J., R. Bishop, F. W. Brenner, T. H. Roels, N. Bean, and R. V. Tauxe. 2001. The changing epidemiology of Salmonella: trends in serotypes isolated from humans in the United States, 1987–1997. J. Infect. Dis. 83:753–761. 53. Olsen, S. J., L. C. MacKinnon, J. S. Goulding, N. H. Bean, and L. Slutsker. 2000. Surveillance for foodborne-disease outbreaks—United States, 1993– 1997. MMWR CDC Surveill. Summ. 49:1–62. 54. Osterholm, M. T., J. C. Forfang, T. L. Ristinen, A. G. Dean, J. W. Washburn, J. R. Godes, R. A. Rude, and J. G. McCullough. 1981. An outbreak of foodborne giardiasis. N. Engl. J. Med. 304:24–28. 55. Portnoy, B. L., P. A. Mackowiak, C. T. Caraway, J. A. Walker, T. W. McKinley, and C. A. Klein. 1975. Oyster-associated hepatitis: failure of shellfish certification programs to prevent outbreaks. JAMA 233:1065–1068. 56. Potasman, I., A. Paz, and M. Odeh. 2002. Infectious outbreaks associated with bivalve shellfish consumption: a worldwide perspective. Clin. Infect. Dis. 35:921–928. 57. Reeve, G., D. L. Martin, J. Pappas, R. E. Thompson, and K. D. Greene. 1989. An outbreak of shigellosis associated with the consumption of raw oysters. N. Engl. J. Med. 321:224–227. 58. Ruttenbur, A. J., B. G. Weniger, F. Sorvillo, R. A. Murray, and S. A. Ford. 1984. Diphyllobothriasis associated with salmon consumption in Pacific Coast states. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 33:455–459. 59. Schantz, P. M. 1989. The dangers of eating raw fish. N. Engl. J. Med. 320:1143–1145. 60. Shapiro, R. L., S. Altekruse, L. Hutwagner, R. Bishop, R. Hammond, S. Wilson, B. Ray, S. Thompson, R. Tauxe, and P. M. Griffin. 1998. The role of Martha Iwamoto is a medical epidemiologist with the Division of Healthcare Quality Promotion, National Center for Zoonotic and Emerging Infections, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Previously, she was a medical epidemiologist with the Enteric Diseases Epidemiology Branch and worked with surveillance of foodborne bacterial infections. She is board certified in pediatrics and preventive medicine. Her undergraduate education was at Davidson College, Davidson, North Carolina; she received her medical degree at Medical College of Georgia in Augusta, Georgia; and she received a Master of Public Health degree from the Rollins School of Public Health, Atlanta, Georgia. She completed her clinical training in pediatrics at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Virginia. She trained in CDC’s Epidemic Intelligence Service and Preventive Medicine Residency Program. Tracy Ayers is an analytical epidemiologist in the Division of FoodBorne, Bacterial and Mycotic Diseases at CDC. She served as a surveillance coordinator for the Hawaii State Department of Health for 4 years, where she had the opportunity to work on several large-scale surveillance systems and analytical projects. She began her employment with the CDC in 2005 and has been involved in several crosscutting activities within the division, with a focus on food-borne attribution. SEAFOOD-ASSOCIATED INFECTIONS 61. 62. 63. 64. 65. 66. 67. 68. 69. 70. 411 Gulf Coast oysters harvested in warmer months in Vibrio vulnificus infections in the United States, 1988–1996. J. Infect. Dis. 178:752–759. Shapiro, R. L., C. Hatheway, and D. L. Swerdlow. 1998. Botulism in the United Sates: a clinical and epidemiologic review. Ann. Intern. Med. 129: 221–228. Sobel, J., and J. Painter. 2005. Illnesses caused by marine toxins. Clin. Infect. Dis. 41:1290–1296. Tauxe, R. V. 1991. Salmonella: a postmodern pathogen. J. Food Prot. 54: 563–568. Tauxe, R. V., and A. T. Pavia. 1998. Salmonellosis: nontyphoidal, p. 613–630. In A. S. Evans and P. S. Brachman (ed.), Bacterial infection of humans: epidemiology and control, 3rd ed. Plenum Publishing Corporation, New York, NY. Tranter, H. S. 1990. Foodborne staphylococcal illness. Lancet 336:1044– 1046. Wainwright, R. B., W. L. Heyward, J. P. Middaugh, C. L. Hatheway, A. P. Harpster, and T. R. Bender. 1988. Food-borne botulism in Alaska, 1947– 1985: epidemiology and clinical findings. J. Infect. Dis. 157:1158–1162. Wasley, A., S. Grytdal, and K. Gallagher. 2008. Surveillance for acute viral hepatitis—United States, 2006. MMWR CDC Surveill. Summ. 57:1–24. Widdowson, M., A. Sulka, S. N. Bulens, S. Beard, S. S. Chaves, R. Hammond, E. Salehi, E. Swanson, J. Totaro, R. Woron, P. S. Mead, J. S. Bresee, S. S. Monroe, and R. I. Glass. 2005. Norovirus and foodborne disease, United States, 1991–2000. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 11:95–102. Wittner, M., J. W. Turner, G. Jacquette, L. R. Ash, M. P. Salgo, and H. B. Tanowitz. 1989. Eustongylidiasis—a parasitic infection acquired by eating sushi. N. Engl. J. Med. 320:1124–1126. Yoder, J., V. Roberts, G. F. Craun, V. Hill, L. Hicks, N. T. Alexander, V. Radke, R. L. Calderon, M. C. Hlvasa, M. J. Beach, and S. L. Roy. 2008. Surveillance for waterborne disease and outbreaks associated with drinking water and water not intended for drinking—United States, 2005–2006. MMWR CDC Surveill. Summ. 57:39–62. Barbara E. Mahon received her M.D. and clinical training in pediatrics from the University of California, San Francisco, and her M.P.H. from the University of California, Berkeley. She trained in CDC’s Epidemic Intelligence Service (EIS). Dr. Mahon leads the FoodNet and Outbreak Surveillance Team in the Enteric Diseases Epidemiology and Surveillance Branch at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The team is responsible for the FoodNet active food-borne disease surveillance system and for national surveillance for outbreaks of food-borne disease. It conducts epidemiologic studies of the burden, trends, and food source attribution of food-borne diseases caused by Salmonella, Listeria, and Escherichia coli O157, among other pathogens. Dr. Mahon has a broad background in infectious disease epidemiology, as she has worked on food-borne diseases, vaccine-preventable diseases, and sexually transmitted diseases in academic and industry positions as well as in government. She holds an adjunct faculty appointment at the Boston University School of Public Health. David L. Swerdlow is Senior Advisor for Epidemiology and Emergency Response, National Center for Immunizations and Respiratory Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. He has served in the pandemic influenza H1N1 response since April 2009, as co-team leader of the Regional and Epidemiologic Field Investigations Team and co-team leader of the Epidemiology and Laboratory Task Force. Previously, he was team leader of the National Surveillance Team, Enteric Diseases Epidemiology Branch. The team conducted national surveillance for food-borne bacterial infections, including seafoodassociated diseases. He is board certified in internal medicine and infectious diseases. His undergraduate education was at the University of California, San Diego, and he graduated from Harvard Medical School in 1986. His internal medicine residency was at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he completed his infectious diseases fellowship at the Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. He was in the Epidemic Intelligence Service at CDC from 1989 to 1991.