* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download 10. Unit review - rmeekportfolio

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

Current Electricity Unit Plan

Instructional Goals

1.

The electric field model developed previously is the agent for charge flow in a

conductor.

A charge imbalance produces an electric field. The resulting potential difference can

be measured with a voltmeter.

Without an external source of energy, charges move in such a way to restore the

balance of charge. (transient condition)

With an external device (battery or generator) a charge imbalance can be sustained.

(steady state condition)

2.

Current is the "flow rate of charge" or quantity of charge per unit time passing a

cross-sectional area in the conductor.

The ammeter is a device to measure flow rate.

By contrast, drift velocity is the average speed of the individual charge carriers in the

conducting medium.

Current is constant in a steady-state circuit.

3.

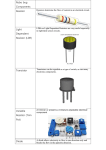

The internal structure of a material hinders the flow of charge driven by the

electric field. This is known as resistance.

Despite the force applied by the electric field, charge quickly reaches a terminal

velocity in a steady-state circuit due to the interactions between the charge carriers

and the atoms in the conducting material.

The amount of resistance is a function of the material (resistivity), the cross-sectional

area and the length of the conducting material; resistivity increases with temperature.

In ohmic materials, resistance is the constant of proportionality between potential and

current

(V I).

In a non-ohmic material, potential is no longer directly proportional to current. (For

example: for a light bulb filament, V I2).

4.

For simple series and parallel circuit arrangements, conservation of energy and

charge can be demonstrated.

The energy dissipated by resistive elements in a circuit equals the energy provided by

the external source.

The total quantity of charge moving in a circuit remains constant. The quantity of

charge in a given branch is inversely proportional to the resistance in that branch.

5.

The power dissipated by resistive elements is a function of both potential

difference and current.

6.

Representational tools include:

maps of surface charge distribution

schematic diagrams to represent circuits.

Sequence

1. Lab 1- What's happening in the wires?

2. Worksheet 1: Fields and potential difference in circuits

3. Lab 2: Charge distribution and potential difference

4. Resistance of Graphite Lines Lab

5. Lab 3: Discovering Ohm’s law

6. Lab 4: Series & Parallel Circuits

7. Water Analogy to Electric Circuits:

8. Quiz 2: Complete paths, light bulbs, ohm’s law

9. Worksheet 3 & 4: Series Circuit and Parallel Circuit Calculations

10. Extension: Series-Parallel Combination Circuits

11. Review

12. Test: Multiple Choice and Series-Parallel calculations part 2

OVERVIEW

Traditionally, circuits are treated as a separate case from electrostatics. When circuits are

introduced, the somewhat elusive concept of "potential difference" becomes even more

obscure and the meticulously developed concept of the electric field is abandoned

altogether. Students are left memorizing several "rules " (Kirchoff's laws, Ohm's law)

with little comprehension of the underlying physics. Vague thoughts of "voltage" as

some kind of "pressure" may be introduced, which not only confuses the cause of charge

motion with its effect, but is also utterly disconnected to prior treatments of electrical

potential.

The material developed here is an attempt to strongly bridge circuits with electrostatics.

Starting with the ideas (developed in Unit 2) that a separation of charge (the presence of

a net + or - charge) results in an electric field and in response to this field mobile charge

carriers move, students develop a more consistent model of circuits. In a circuit, the

battery (or other emf source) does work to maintain a charge separation, and thus creates

an electric field within the conducting elements ("conductors" or wires, and resistors).

At the resistors, mobile charges accumulate at one side, resulting in a charge separation

that produces a relatively large field compared to that within the conductor. Thus, charge

carriers experience most of their drop in potential at the resistors.

The rate of charge flow (current) is emphasized as a flow rate, or quantity of charge

moving through a cross-sectional area per unit time. This is distinguished from drift

velocity or average speed of a charge through a conductor. In a simple circuit, current is

the same in conductors and (series) resistors; drift velocity is not. In response to the

stronger electric field in resistors, drift velocity increases. Resistance in effect restricts

the area through which charge can flow. Thus, the restricted area through which charge

can flow effectively "evens out" the current.

Students develop a mathematical model for resistance by conducting a more-or-less

"typical" Ohm's Law Lab. They vary voltage supplied to a circuit containing an ohmic

(ceramic power resistor) and from the linear graph of V vs. I derive the mathematical

model for resistance. The conceptual model for resistance can be developed through an

analogy. Marbles rolling down an inclined pegboard studded with dowels or nails model

charge carriers traveling under the influence of a uniform field, encountering hindrance

from other material elements. The more hindrance, the lower the flow rate (for a given

field tilt of the ramp).

Finally, students explore more complex circuits, containing two or more resistors in

series and/or parallel arrangement. Students are challenged to identify patterns relating

an overall quantity (e.g. voltage supplied) to resistor-specific quantities (e.g. voltage drop

across each resistor). With the ammeter and voltmeter, they collect data, and through

whiteboarding and discussion, the patterns are delineated. These patterns are then

checked against the models developed throughout to drive home the overall consistency.

Notes on circuitry conventions

Charge Flow Conventions:

The choice of direction of charge flow is left to the instructor. While we

recognize that electrons are the mobile charge carriers, the convention of discussing

current in terms of the flow of positive charge carriers (or holes) is favored by many

physics texts and is the preferred convention in electronics. The use of this convention is

due not only to the historical development but also to the fact we more naturally associate

the term "positive" with a surplus and "negative" with a deficit of charge. The way we

have defined the direction of the electric field and our designation of the positive terminal

of a battery as having greater electric potential favors the use of the Franklin convention.

Resistance in the wires of a circuit

During the introductory activities to this unit, it is not assumed that wires are ideal

conductors

(R = 0). The resistance (a term not used until the second lab) is found to be small, as seen

in small potential changes across the wires in the closed circuit of Lab 1. Later in the

unit, this small resistance is ignored in analyzing circuits. Each teacher will have to

decide how far to go in addressing the internal resistance of the connecting wires. This

can be circumvented, in the Ohm's Law Lab, by having the students measure the potential

across the resistor in the circuit, instead of across the battery.

1. Lab 1–What's happening in the wires?

This lab is divided into two sections; please refer to student lab sheets included in

materials.

Part I - Students monitor voltages in several parts of a circuit containing a charged

capacitor, and witness the transient field within the conductors during discharge.

Part II - Students discharge the capacitor through long and round bulbs. They notice

that the transient field takes significantly longer to disappear. The implication is

that the bulb “interferes” with the redistribution of charge carriers and the

restoration of the balanced distribution. This is visualized as the bulb filament

acting as a “bottleneck”, causing charge carriers to “pile up” as they pass through

the filament. These points should be drawn out of the discussion of student

models that should follow part II.

Purpose(s)

This introductory activity and the accompanying two-part lab is designed to lead students

from the concept of the electric field and electric potential to a more dynamic system

involving bulk motion of charge carriers within a conductor (current). By the end of this

lab, the students should be able to:

1. Recognize that charge carriers move in conductors as a result of electric fields set up by

an unbalanced distribution of charge within the conductors1 In the case of the discharging

capacitor, this imbalance is short lived, as charge is quickly redistributed.

2. Recognize a light bulb or other resistor constitutes a “bottleneck” that reduces the flow

of charge carriers, and “piles up” mobile charge on one side. As a result of the

unbalanced charge distribution across a resistor, a strong electric field exists in it.

3.

Recognize that the fields in the circuit (wires and resistors) do work on the charge

carriers, transferring their potential energy to other modes such as heat and light (and

charge carriers’ kinetic energy). Because the field in the resistors is so much stronger

than in the wires, almost all of the energy transfer (working) done in the circuit occurs in

the resistors. The case of the steady state circuit with a battery will be addressed in the

following lab.

Apparatus

- battery pack with three – D cells

- voltage probes with computer interface

- data collection software (Vernier Logger Pro, PASCO Science Workshop)

- capacitor (CASTLE 25,000 uF blue or 100,000 uF silver is ideal)

1

According to Sherwood and Chabay, the charge distribution responsible for the electric field is actually

on the surface of the conductor and forms a gradient along the length of the conductor proportional the

magnitude of the field. Additional information can be found in their textbook, Electric and Magnetic

Interactions, published by Wiley and Sons, 1995. A simplified treatment can be found in the optional

reading.

- mini light bulbs (#14 and #48)

Pre-lab discussion

NOTE: Conventional current — motion of positive charge—will be used throughout

this lab. If you prefer, you can cast all that is to follow in terms of electron flow.

The pre-lab discussion begins with the review of a capacitor made of two aluminum pie

pans separated by about 2 inches of air as first shown in unit 1.

Remind students that the uneven charge distribution produced an electric field which

exerted a force on the pith ball suspended between the plates. The excess charge on one

plate was transferred to the other by the action of the pith ball shuttling back and forth

between the plates. Now point out that we’ve only examined the field between the plates.

What would happen if the two plates were connected by a wire? Would a field exist in

the wire? Lacking the ability to place a test charge within wires can we deduce the

presence of a field within them? This lab should help students get a sense of what is

taking place in the wires.

Lab performance notes - Parts I and II

This lab can be performed as a teacher-led interactive demonstration, or with groups of

two or three students (preferable), depending on the availability of materials. It consists

of two parts, and a class-wide discussion is recommended, using whiteboards or other

similar devices, to pull the salient features out of each part. This may need to be done

after each part of the lab to be sure students are developing the concepts adequately.

Students will be using a voltmeter to detect the presence or absence of a field (stress the

concept developed at the end of Unit 2 that changes in electric potential only occur along

or against electric field lines). It is stated in the student materials, but worth

reiterating, that the existence (and relative strength) of an electric field will be

qualitatively inferred by the presence of a difference in potential. They can,

however, collect quantitative data on differences in potential, and indeed it is important

that they do so.

The ideal voltmeter for this activity is a set of voltage probes connected via an interface

(e.g. Vernier’s Lab-Pro or ULI or PASCO’s Science Workshop interface). This allows for

real-time collection of sometimes very transient (≈ 0.05 seconds) voltages, and allows

them be saved and later quantitatively examined. The voltages in this activity range

widely, from about 5 V to about 0.05V, easily dealt with by zooming in and out of a

voltage-time graph. For best results, sampling rates of 100-250 Hz have worked well, but

feel free to experiment.

Fig 1- Discharge of

capacitor through

connecting wires.

A digital voltmeter works too, but the transient voltages are difficult to read. The meter

will flash a value but neither the time for the voltage “spike” nor its “shape” can be

appreciated by the student. An analog meter will twitch, but that is even harder to read,

and the range of sensitivity required call for at least two meters (volts and millivolts).

It is imperative to place the black lead of the voltmeter or voltage probe at the starting or

reference point and to "lead with the red probe". In this way, increases in potential are

indicated by (+) voltmeter readings; (-) readings indicate that potential decreases.

Teachers are strongly encouraged to work through this lab prior to having the students

perform it in class.

Fig 2Change in potential

of connecting wire

when circuit is

completed.

Post-lab discussion

The lab parts are guided, but there should be some closure with the entire group. Groups

should prepare whiteboards of their final explanations of what is going on in the circuit

with the capacitor in it. In the ensuing discussion, it should be brought out that:

1. The battery does working on the charge carriers when" charging" the capacitor.

This moves charge from one plate to the other, creating an unbalanced

distribution until it is discharged.

2. The transient drop in potential from B to C needs to be accounted for. Note that

at C in the left diagram, the charge density is somewhat less than at B due to the

migration of charge across the boundary. This difference in charge density sets

up the field that drives the charge through the wires. When the charge is

distributed equally, the difference in potential between B and C returns to zero.

3. The "bottleneck" at the resistor results in a much, much stronger field (as

measured by a larger decrease in potential) than in the wires.

4. The field strength at different points within the circuit is a result of the

distribution of the charges at those points.

5. This would be a reasonable place to introduce the idea that surplus charge resides

on the surface of the conductor. Reading 1: charge distributions, which

describes the charge mapping, provides an excellent resource for students.

2. Worksheet 1: Fields and potential difference in

circuits

3. Lab 2–Charge distribution and potential difference

in circuits

Purpose(s)

This activity clarifies how a battery can maintain a constant charge flow (current) through

a simple circuit containing a resistor by working. It also develops charge distribution

mapping techniques as a tool for describing and predicting the fields within elements of

the circuit.

Apparatus

one battery pack with 3 D-cell batteries

6 Wires (2 of them with no insulation)

mini light bulbs (#14 and #48)

two bulb holders

digital voltmeter

Pre-lab discussion

Students should be reminded that in the previous lab

they learned that the charge distribution throughout the circuit is responsible for the field

that drives the current within the circuit.

This lab is an extension of lab 1, where the students used capacitors within a single

resistor circuit to describe the flow of charge due to separation of charges and the

resulting fields. In this activity students will use a battery pack to replace the charged

capacitor from lab 1.

Lab performance notes

Again, it is important to remind students that they should measure potential

differences “from black to red.” At this stage, it has not yet sunk in that (+) differences

represent gains and (-) differences represent losses in energy of the charge carriers.

Remind them that sign is as important as the reading of the magnitude on the multimeter.

Post-Lab discussion

After lab 1 and worksheet 1, the capacitor in the circuit is replaced by a battery.

Students will notice that the transient field observed in the conductor during the discharge

of the capacitor is replaced by a sustained field. The strong implication is that the

imbalance in charge carrier distribution is being actively maintained. The only “culprit”

possible for this is the battery. A quick “tour” of the circuit with the voltmeter reveals an

increase in electric potential across the battery (accompanied by a relatively strong

electric field), small decreases (and thus weak fields) in the conductors, and a large

decrease (and large field due to charge “pile

up”) at the bulb(s).

The use of different bulbs will result in

different drops in potential across the bulbs. At

right is a sample graph for a circuit in which

the charge moves first through a round (#48)

bulb before it moves through a long (#14) bulb.

Slight, but not negligible decreases in potential

should be observed in the wires as well.

Students may be perplexed by the fact that the

round (#48) bulb will failed to light (or barely

glow) while the long (#14) bulb is bright. The explanation lies in the much lower drop in

potential across the filament of the round bulb - the energy lost by the charge carriers is

insufficient to heat the filament to incandescence.

The final picture to be painted is that of the battery doing active work to maintain an

unbalanced charge distribution. This results in a continuous electric field that causes

mobile charge carriers to move in the conductors. The battery does work on the

charge carriers against an electric field, increasing the charges’ potential energy at the

expense of the battery’s chemical energy. One should make sure that students take

note of this. Batteries don’t run out of charge, but the ability to move the charge

carriers up-field. (If a Genecon or other hand-cranked generator is used, the charge

carriers’ potential energy is increased at the expense of the “cranker’s” mechanical

energy). Have the students add the potential differences moving around the circuit in

steps 6 and 7. If they made their measurements carefully, they should find that the

sum of the ∆V’s is nearly zero.

Because charge motion is present, it would be appropriate at this time to develop a model

of current. (This foundation needs to be laid before the activity developing Ohm's Law.)

One way to do this is to have students predict/describe the motion of charge carriers in the

wires as opposed to in the bulb filament. Their prediction should be along the lines of

"less motion" in the wires, owing to the weaker field present there. Ammeters can be

introduced as a "device to measure the motion of charge", and students can use them to

measure the current leaving the battery vs. the current leaving the bulb filament. Students

may be surprised to see it is the same.

Assure students their intuition is right on one count: the charge carriers must (on average)

be moving faster in the stronger field in the filament. Introduce the idea that the charge

carriers motion will be interfered with by the other components of the conductors (atoms,

other mobile charge carriers, etc.), but that in a stronger field, their average drift velocity

should be greater.

Point out that the wires are effectively much wider than the filament: the represent

a "wider hallway." Have students consider the quantity of charge carriers passing a

particular point in the wires during one second. They are moving slowly, but the hall is

wide. Now consider the quantity of charge carriers moving through the filament. They

are moving much faster, but their "hallway" is much narrower. Thus it is possible that in

both cases, the same number of charge carriers pass a point each second. Define this

q

"flow rate" as current: the quantity of charge passing a point each second I

t . In a

resistor, the drift velocity is greater, but the current is the same as that in the wires. The

rate of charge flow (current) is emphasized as a flow rate, or quantity of charge moving

through a cross-sectional area per unit time. This is distinguished from drift velocity or

average speed of a charge through a conductor. In a simple circuit, current is the same in

conductors and (series) resistors; drift velocity is not. In response to the stronger electric

field in resistors, drift velocity increases. The increased velocity of the charge carriers

produces more collisions with the atoms in the conducting material, accounting for the

increase in temperature of conductors when charge passes through them. Resistance, in

effect, restricts the area through which charge can flow. Thus, the restricted area through

which charge can flow effectively "evens out" the current. The conceptual model for

resistance can be developed through an analogy. Marbles rolling down an inclined

pegboard studded with dowels or nails model charge carriers traveling under the

influence of a uniform field, encountering hindrance from atoms in the material. The

more hindrance, the lower the flow rate (for a given field).

This can be further demonstrated by a line of five students standing abreast (large

area for charge flow: a conductor) who move slowly to cross a line in one second, while

five students one behind the other (small area for charge flow: a resistor) must move

quickly. The flow rate is the same, while the drift velocity (people per second) differs

greatly.

4. Quiz 1

5. LAB 3 – Ohm's Law lab

Purpose

To investigate the relationship between voltage and current for a simple circuit with

constant resistance.

Apparatus

Variable voltage power supply or four D-cell and battery holder

Ceramic power resistors (5-50 ) or rheostat (different groups should have different

value resistors)

Connecting wires

Milliammeter and voltmeter or multi-meter or appropriate computer probes

One CASTLE “long” bulb (for optional extension)

diode (for optional extension)

Pre-lab discussion

Show students a simple circuit (bulb, battery and wire), and pose the question, “What do

you suppose is the relationship between the current and the potential difference that

causes the charge to move through the circuit?” Review the role of the battery: it does

work to maintain an imbalance of charge in the circuit. The greater the imbalance, the

stronger the field in the wires and the resistor, resulting in a stronger force on the mobile

charge carriers in the circuit. The stronger the force, the greater the flow rate.

Performance notes

If your students use the power supply, it is easy for them to adjust the voltage until the

ammeter reads a given value, then determine the potential drop across the resistor with a

multimeter. If they use a 4-cell battery pack, even though students will vary the potential

difference, making it the independent variable, you should encourage students to plot "V"

on the vertical axis. Indicate that if the graph is made this way it will provide more

useful information, not unlike the way we placed time on the horizontal axis in the ball

on an incline lab. Students can easily collect data on two different resistors, allowing

them to plot both sets of data on the same set of axes.

Optional extension - flashlight bulb

Have students perform the experiment again, this time with a long (#48) bulb instead of a

resistor.

Post-lab discussion

Most students readily see that the potential difference is proportional to the current and

that the slope is very nearly equal to the rated resistance of the resistor. Through a

discussion of the meaning of the slope, suggest that it represents the amount of energy

transferred to each coulomb of charge to result in a one ampere current. The greater the

value, the more the battery (or power supply) has to work for each ampere of current.

Thus, the slope is a measure of the circuit’s resistance to charge carrier motion.

Introduce “Ohm’s Law” as a re-arrangement of the V = RI equation they obtain from the

graph.. Use the term "ohmic" to describe a resistor with a linear dependence of current

on voltage.

If students collect data with the light bulb they will find that they will have to square I to

get a linear graph (V I2). In the post lab discussion, challenge the students to account

for the difference in behavior between the bulb and the resistor. The thermal motion of

the filament’s atoms increases with the current, increasing the resistance to the movement

of charge carriers. Thus as the potential difference is increased, the increase in current

lags behind. Resistive elements that do not yield a linear plot are labeled "non-ohmic."

These data can also be used to develop the concept of electric power. Remind students

that in the past we've seen that the area under a graph can have physical significance.

Ask them to consider the meaning of the area under the V vs. I graph. Remind them that

the volts is a

joule/ coulomb, and the ampere is a coulomb/ second. An examination of the units

obtained when potential difference and current are multiplied reveals the units of power.

joule

coulomb joule

watt

coulomb

s

s

The area under the Ohm's law curve is thus: P 1 2 Vfi nal I . Note that this is average

power dissipated by the resistor as the voltage increased (since V 1 2 V f ). In circuits

where V doesn't change, P = VI. Manipulation of these two equations obtained from the

graph allows one to write the power equation in terms of I or V.

P IV

P I IR substituting IR for V

P I2 R

P IV

V

V substituting

R

V2

P

R

P

V

for I

R

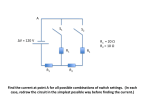

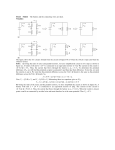

6. LAB 4 – Series and parallel arrangements

Purpose

After students have determined the relationship between potential difference, resistance

and current for a single resistor they examine these relationships with combinations of

resistors in series and parallel.

Apparatus

Variable voltage power supply or three D-cell and battery holder

Ceramic power resistors (5-50 - two per group)

Connecting wires

Milliammeter and voltmeter or multi-meter or appropriate computer probes

Pre-lab discussion

Sketch the circuit schematic above and ask what measurements could be made to

study how the combination of resistors might affect the current and potential difference at

different parts of the circuit. Students should be induced to measure the current before

R1, between R1 and R2, and after R2. They should measure the potential difference across

the battery, ∆VT , and across each resistor.

For the parallel circuit, they should measure the current in four places: before and after

the branches as well as in each branch.

Lab performance notes

Due to the number of rearrangements of the connecting wires that have to be made, it is

recommended that part of the class examine the series combination of resistors, while the

remainder examines the parallel combination. As an alternative procedure, the instructor

could assemble the circuit and make the measurements using current and voltage probes

connected to a computer with projection capability. The paired resistors should have

resistances that are simple integer multiples of one another (e.g., 5 and 15 , or 10 and

50 ).

Post-lab discussion

When students compare the data for the series circuit, they should be able to see charge is

conserved in its journey through the circuit, I1 I2 I3 , and that energy is conserved as

well VT V1 V2 0 . Furthermore, the potential difference across each resistor is

V

R

proportional to the resistance: 2 2 . Since the magnitude of the gain in potential

V1 R1

across the battery is equal to the sum of the loss in potential across the two resistors, it

follows that the equivalent resistance of the circuit is simply the sum of the resistance

offered by the two resistors.

VT V1 V2

IT RT I1 R1 I2 R2

RT R1 R2

Substitute IR for V

Divide through by I since the current is the same everywhere

For the parallel circuit, students should also find that charge is conserved

Ibefore I1 I2 Iafter , and that the current in each branch is inversely proportional to the

I

R

resistance 2 1 . Students will also see that the potential differences across each

I1 R2

branch are equal, but will usually find that they are smaller than the terminal voltage

provided by the battery. At first, they are troubled by this apparent non-conservation of

energy, but if they consider what happened in the first lab, they should realize that the

losses in potential in the connecting wires are not negligible. This is especially true if the

resistors used have relatively small resistance. The losses are more noticeable here than

in the series circuit since the current through the circuit is so much greater due to the

greatly reduced effective resistance.

In any event, below is a derivation for the expression for equivalent resistance for

resistors in parallel.

IT I1 I 2

VT

V V

1 2

RT

R1 R2

1

RT

1

R1

1

R2

Substitute

V

for I

R

Divide out the V’s since VT V1 V2

7. Worksheet 2

This worksheet serves to deploy the relationship developed in labs 3 and 4.

8. Quiz 2

9. Worksheet 3

This worksheet gives students opportunities to apply the concepts to combination

circuits, as well as solve more complex AP-type problems.

10. Unit review

11.

Test