* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download FIRST DRAFT: Anderson 03/2001

Island restoration wikipedia , lookup

Occupancy–abundance relationship wikipedia , lookup

Biodiversity action plan wikipedia , lookup

Reforestation wikipedia , lookup

Reconciliation ecology wikipedia , lookup

Tropical Africa wikipedia , lookup

Old-growth forest wikipedia , lookup

Habitat conservation wikipedia , lookup

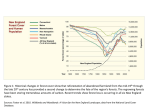

Biological Dynamics of Forest Fragments Project wikipedia , lookup

MULTIPLE SCALE CONSERVATION OF MATRIX FOREST: THINKING INSIDE THE BLOCKS FIRST DRAFT: Anderson 03/2001 For review by the matrix forest working group Josh Royte, Barbara Vickery, Doug Bechtel, Bill Brown, Judy Benedict, Julie Lundgren, John Roe, Frank Lowenstein, Lise Hanners, Bill Toomey, Jim Howe, Ana Ruesink, Judy Ross, Bill Patterson, Sandy Bonanno, Rodney Bartgis, Anne Heasly, Doug Samson, Stephanie Flack, Susan Young, Jim Thorne, Mark Anderson, Judy Dunscome, Karen Lombard, Greg Kehm, Charles Ferree, Liz Thompson 1 MULTIPLE SCALE CONSERVATION OF MATRIX FOREST: THINKING INSIDE THE BLOCKS 0: OBJECTIVE 1: BACKGROUND AND APPROACH: 1a) Matrix forest and functional landscape concepts: 1b) Communities and Systems as coarse filters for total biodiversity: 1b1) Source-sink dynamics and source habitat: 1c) Viability as Resistance and Resilience: 1c1) Biological legacies and Time frames: 2) ESTIMATING VIABILITY: SIZE, CONDITION, LANDSCAPE 2a) Size Criteria 2a1) Scaling factor 1: Disturbance factors. Stand replacing patches vs. total disturbance area. Critical area needed to absorb and buffer disturbance: 2a2) Scaling factor 2: Coarse-filter Functions Forest bird assemblages. Mammal assemblages. 2a3 Synthesis of the Scaling Factors 2b) Condition Criteria 2b1) Negative Impacts: Stress, Fragmentation and Roads. Roads as barriers Roads as conduits 2b1) Positive Attributes: Biological Legacies Biological Legacies and Resistance / Resilience . Biological Legacies and Species Richness Biological Legacies and “Source-Area Characteristics” 2b3) Quantifying Biological Legacies: Coarse Woody Debris 2c) Landscape Context Connectivity Working Group June 11-12 2 MULTIPLE SCALE CONSERVATION OF MATRIX FOREST: THINKING INSIDE THE BLOCKS draft M. Anderson 3/2001 0: OBJECTIVE The objective of this document is to 1) clarify goals for conserving matrix forest occurrences, 2) expand upon the methods used to assess viability for communities (at all scales) in the northeast and east division ecoregional plans and 3) develop the concepts and data more completely for site conservation planning and setting restoration goals. This document summarizes discussions held among a wide variety of ecologists at TNC field offices, Natural Heritage programs and the academic community (see acknowledgements). 1: BACKGROUND AND APPROACH: 1a) Matrix forest and functional landscape concepts: This document assumes a basic familiarity with the concepts of matrix forest, conservation at multiple scales and functional landscapes (Fig 1a.1). Details on these concepts may be found in Poiani et al. 2000, Anderson 1999, Anderson et al.1999. Throughout the document the viability of matrix forest systems is discussed in relation to two central factors:1) their value as a coarse filter for all biodiversity and 2) their functionality with respect to ecological processes across all scales. 1b) Communities and Systems as coarse filters for total biodiversity: A primary strategic value of ecological system/community protection is as “coarse filters” for all biodiversity (Hunter 19xx). Although the Nature Conservancy defines and maps communities based on their vegetation structure, composition and environmental setting (Grossman et al. 1999), we recognize that vegetation typically represents less than 15% of the total biotic assemblage of an ecological community ((Steele and Welch 1973, Falinski 1986, Franklin 1993). The majority of species are smaller types (invertebrates, fungi, and bacteria) that carry out critical ecosystem functions such as decomposition, nutrient cycling or that provide a food chain base for associated vertebrates (Wilson 1987, Franklin 1993). This creates a potential problem in that a small or fragmented example of a community may be identified 3 taxonomically, based on its vegetation, even if it is unlikely to contain all of its typical biota. For the “coarse filter” to be effective, ecological systems and communities must be conserved at their natural size scale and in adequate condition to insure that they contain all their associate species. For example a 30-acre patch of 40 year old northern hardwood forest is unlikely to contain multiple breeding examples of all the flora and fauna associated with that community. This issue is discussed further below under Size and Condition. 1b1) Source-sink dynamics and source habitat: In addition to simply “containing” species, if the intention of a conservation reserve system is to stabilize the loss of biodiversity within an ecoregion then it is critical that the occurrences exhibit (or develop) the characteristics to insure that they function as source-habitat for those species (Pulliam 1998). Source-sink population dynamics, because of their implication on the role of reserves in maintaining biodiversity over large areas, is an important component in reserve selection and design. Originally, source areas were conceived of as a population attribute defined by the demographics of the population, specifically the per-capita reproductive and mortality rates (Pullium 1991). In testing the source-sink model however, such an array of temporal and spatial variation in species densities have been uncovered it is proving difficult to confirm whether a local population is a source or a sink based solely on the measurement of demographic parameters (Diffendorfer 1999 Oikos). For example, excess individuals from source populations may immigrate into lower quality source areas, or high quality source areas may temporarily over-crowd, depressing the per-capita reproductive output and creating “pseudo-sinks” (Watkinson and Southerland 1995). In spite of these complexities, the source sink model has remained an important model for understanding population dynamics. Empirical evidence supporting the model has been reasonably shown for plants (Bastreta 1991, Mook et al. 1989, Werner and Caswell 1977, Charron and GagXX 1991, Menges 1990, Keddy 1981:1982, Kadmon 1993), mammals (Henderson et al. 1985, Sullivan 1979, Dunbar 1987, Carl 1971, Blondel et.al. 1992, Slade and Balph 1974), and birds (King and Mewaldt 1987, Robinson and 1996, add the frag references here). Alternatively, for the purposes of community/system evaluation, we adopted Pulliam’s (1998) concept of source habitat, defined here as habitat where, on balance, over decades or centuries, the reproductive success of most species exceeds mortality and a local surplus of individuals is generated 4 Switching the emphasis from the local population dynamics to the attributes of a particular habitat or areas allows the concept to be characterized with respect to structural and compositional attributes of community occurrences. This definition recognizes that individuals within source areas may exhibit complex relationships with individuals outside the defined areas and be dependent on larger landscape scale connections for long term maintenance (Holmes et al. 199x, M. Reed pers.com.). In summary we defined a viable occurrence, with respect to its value as a coarse filter for biodiversity, as an occurrence that is likely to contain, provide breeding habitat and export individuals of all their typical associated flora and fauna. This criteria insures that the reserve will play a vital role in maintaining the population of many common or declining species within the larger area of the ecoregion by providing a source of emigrants and creating disperser pressure (Pulliam et al. 1992). The characteristics that insure an occurrence will function as source habitat are discussed in detail under condition. 1c) Viability as Resistance and Resilience: With respect to ecological processes, we defined a viable ecological system as one that expresses the characteristics of resistance, the ability to absorb small perturbations and to prevent them from amplifying into large disturbances, and resilience, the capacity to return to the original level of productivity and species composition following disturbance (Holling 1973, Karr 1991). Systems with these characteristics may also exhibit persistence over long time periods (centuries), not in a static manner but in a dynamic state that fluctuates within some bounds of variation (Holling 1973, Pimm 1984). Thus for the purposes of this discussion, a viable occurrence of a community or system is defined as an occurrence that exhibits resistance, resilience, and persistence over centuries. Periodic disturbances are an expected part of how forests, and other natural systems, function (Perry 1994, Foster et al 1998). For conservation purposes it is critical to insure that the ecological processes and disturbances that sustain a particular ecological system/ community are operating within their natural range of variation (e.g. that the community/system is “functional” Poiani et.al. 2000). For coarse scale system types like matrix forest, functionality is predominantly an internal characteristic and is discussed below under size and condition”. For most large patch and small patch communities, functionality is predominantly an external landscape characteristic and is discussed below under condition and landscape context. 5 1c1) Biological legacies and Time frames: During ecoregional planning we used “centuries” as our benchmark, the specific time span over which the occurrence is expected to persist varies with community type. Some herbaceous types are naturally ephemeral (e.g., annual communities which colonize mineral soil). In contrast, forests are dominated by species with life-spans measured in centuries. Multiple generations of the latter require very long time frames. Under natural disturbance regimes the biological legacies (residual characteristics of the existing and previous organisms such as seed banks, perennating organs, nutrient pools, mycorrhizal associations, or coarse woody debris) which accumulate at a site may persist much longer than the above ground biomass of living individuals (Franklin 1985). These legacies have a large effect on the resilience of communities and are discussed further under the section on condition. Direct or immediate threats to an occurrence are not included in this definition of viability, as unexpected human-related disturbances to a site (e.g., the site is slated for development) may alter the persistence of even those community occurrences that are otherwise viable. 2) ESTIMATING VIABILITY: SIZE, CONDITION, LANDSCAPE It is not easy to directly assess whether an occurrence is serving as source habitat for all species or to measure its resistance, resilience and persistence (such measurements are theoretically possible see Halpern 1988 for an interesting example). Alternatively we use three measurable characteristics of an occurrence that correlate closely with these functions: size, current condition, and landscape context (TNC 2000, Poiani et al. 2000, Hunter 1996). The following sections examine each of these attributes individually. 2a) Size Criteria The size of an occurrence is highly correlated with both its species diversity and its resistance/resilience to perturbations (Conner and McCoy 1979, and many other refs). Thus, following the above discussion we developed two separate scaling factors for establishing size criteria. Scaling factor one involved an examination of the scale, frequency and intensity of the natural disturbance regime. In particular, large, infrequent catastrophic disturbances as opposed to smaller scale, more continuous, 6 maintenance disturbances. Scaling factor two consisted of an investigation into the breeding needs of associated flora and fauna such as forest interior birds and mammals, area-sensitive species, keystone species, and species that perform internal biotic functions. The critical scales for these two factors, disturbances and area requirements for associate species, were subsequently synthesized into a single index. What follows is a specific example of setting size criteria for matrix-forming forest in the Northern Appalachian ecoregion (loosely excerpted from Anderson 1999). A similar process has been used in the other northeast/east ecoregions (although not as well documented!!). 2a1) Scaling factor 1: Disturbance events. Long-term maintenance of forest systems is dependent on periodic disturbances (Perry 1994). These disturbance events range in scale and frequency from almost continuous (single tree-fall gap replacement) to large, regional-scale disturbances which cycle at intervals of 100 years or greater (Lorimer 1977, Bormann and Likens 1979, Runkle 1981, Canham and Louks 1984, Canham and Marks 1985, Foster et al. 1988). Disturbance types in the northeast include hurricanes, tornadoes, fire, insect outbreaks, flooding, and ice storms (USDAFS 1998). Each disturbance type has its own spatial pattern, scale, frequency and range of severity. Present vegetation patterns are strongly controlled by interactions between specific disturbance types, the abiotic environment (especially topography), and the vegetation composition and structure at the time of disturbance (Foster et al. 1998). Over extended periods, long lasting patterns of species and ecosystem distribution that represent enduring imprints of disturbance may exist (Whitmore 1974, Turner et al. 1999). Stand replacing patches vs. total disturbance area. It is a certainty that large disturbances will occur across any large forest area (Fig 2a.1); the major questions are then “which types of disturbances are to be expected, with what frequency do they occur, and how is the damage distributed across the landscape?” As disturbances pass across a landscape and interact with the dominant forest types, a mosaic of heterogeneous patches is produced (Fig 2a2, Fig 2a3, Foster et al 1988, Bormann and Likens 1979). In some cases the species composition of the various patches is relatively similar but there are quantitative changes in age distributions and structure. In severe cases, disturbance patches are accompanied by complete destruction (but not necessarily removal) of existing aboveground species biomass and subsequent colonization by rapid growing, light requiring, wind dispersed species that alter the composition of the forest as well as the structure. We were interested in compiling information on the size and 7 distribution of severe disturbance patches created during catastrophic events. These stand-replacing patches were defined as areas of complete alteration of most aboveground biomass and it was to these patches that we scaled the necessary occurrence size. Although the literature on disturbances is fairly substantial, only those empirical studies that contained sufficient detail on the grain and extent of severe disturbance patches were used. Table 2.1 compares some attributes of a number of common disturbances in the Northern Appalachians with the maximum size of severe, stand-replacing, disturbance patches being given in row three. Table 2.1 Comparison of characteristics among infrequent catastrophic disturbances in the Northern Appalachians. The size of stand-replacing disturbance patches is given in row three. Disturbance characteristic Duration Tornado Minutes Hurricane Hours Downbursts Minutes Return interval in years Maximum size of severe patches (acres) Size of total event in acres Insect outbreak Months Ice Storm Flood Days ? Large Fires Weeks /months 400-6000 10 2 Week /months 50-100 100-300 60-200 5000 803 3500 57-150 ? ? ? 1240 K24710 K 12400 K – 5M 1M 12,400K24 M. 247,000K –200 M 12,400 K – 24 K. 12,400 K124,000K Critical area needed to absorb and buffer disturbance: The rate of recovery of a disturbed patch of matrix forest back to its original state is largely dependent of the biological legacies which remain at or adjacent to the site (Peterson and Pickett 1995). Recovery rates are enhanced by new resources (e.g. light, nutrients, mineral substrate and woody debris) released by the disturbance. Although most natural disturbances leave the herbaceous and litter layers relatively intact, the process of full recolonization of the understory on anthropogenically disturbed lands may be on the order of hundreds to thousands of years (Thompson 1980, Duffy and Meier 1992, Motzkin et al. 1996). At the ecoregion level we scaled the size minimums for matrix forest to the grain and extent of severe, stand-replacing disturbance patches expected over 100 year time intervals but the question remains: how much larger than these patches does a reserve area have to be? In the literature, the area needed to insure that a system can absorb, buffer, and recover from disturbance, Pickett and Thompson’s (1978) “minimum dynamic area”, is the subject of debate. Shugart and West (1981) suggested it be 50 times the mean disturbance patch size. Baker (1992) emphasized that it should be scaled not to the mean but to the 8 maximum disturbance size. Peters et al. (1997) suggested it be scaled to the largest disturbance event expected over a 500-1,000 year period. For ecoregional planning we approached the above question by considering what percent of an area could be expected to be in a “severely disturbed” state at any given time under natural conditions. Foster and Boose (1992) studied the effects of the 1938 hurricane over 100s of square miles in New England and estimated that ¼ of the area was severely damaged, another ½ was in a state of moderate damage, leaving about ¼ in a mature or undamaged state. Canham and Loucks (1984) estimated that catastrophic windthrow maintained at least 17-25% of Wisconsin’s presettlement forest in early successional composition and structure. In northeastern Maine, Lorimer (1977) estimated the extent of historic disturbances from presettlement land surveys. He concluded that 16% of the area had been in a early successional state. The studies reviewed suggest that under presettlement conditions about 15-25% of an area may have been expected to be in a severely disturbed state at any given time. Extrapolating from this, we used a general guideline that an occurrence should be about 4 times the size of the maximum, expected standreplacing patch in order to replicate the natural pattern of disturbed to undisturbed forests in New England. The results of this guideline, when plotted on a linear scale, are shown in the upper half of Figure 2a.4. Using the numbers from the previous discussion, the figures for tornado damage in Tionesta (19 km 2 or 4,691 acre stand-replacing patch) suggest about a 19,000-acre reserve size. Scaling to the largest standreplacing patch” at Pisgah forest from the 1938 hurricane suggests a size of (4 x 803 acres) 3212 acres. Likewise, total downburst damage in the Five-Ponds region of the Adirondack mountains suggests an occurrence size of roughly 14,000 acres (4 x 3500) assuming the damage exhibited a roughly tornado-like pattern. Data on the largest stand-replacing burn patches in northern hardwood forest of the White Mountains (57 acres) would suggest a size of only 227 acres (Bormann and Likens (1979). 9 Figure 2a.4. Scaling factors for minimum size of matrix sites in the Northern Appalachians. Scaling factors and Reserve size for Matrix forests in the Northern Appalachians: Fires (NH) DISTURBANCES (4 X's the historic severe-destruction patch size) M. Anderson 1999 Downbursts Fires (SF)? Hurricanes Tornados Fires (SF)? Fisher Lynx Barred Owl SPECIES (25 X's the mean female home range) Moose Neotropical birds Marten Bobcat Spruce Grouse 0 2 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40 // 75 // 150 Reserve size in 1000s of acres Factors to the left of the arrow should be encompassed by a 25,000 acre reserve NH = N. hardwoods SF = Spruce-fir The estimate for spruce-fir is based on mean fire size in Maine (low estimate) and Quebec (high estimate). Neotropical estimates based on Robbins et al. 1989, see text for full explanation. Most references reviewed on disturbance in the Northern Appalachian region provided total or average disturbance extent and lacked sufficient detail on the distribution of large infrequent standreplacing disturbance patches with which to develop size criteria from. For example, Lorimer’s (1977) estimates for total disturbance size in Maine’s spruce-hardwood forests suggest disturbances on the order of 100,000 to 200,000 acres but he did not provide a patch size distribution of disturbance severity. In the case of Pisgah forest (Foster 1938) where both average size and severity distribution was provided, scaling to “four times the largest severe patch” gives results about three times larger than Shugart and West’s (1988) guideline of “50 times the mean patch size” (25 acres x 50 = 1250 acres). This supports the observations of many ecologists that numerically disturbances are mostly a small-scale phenomena but a few large infrequent disturbances probably account for most of the damage and the effects are long lasting (Turner et al 19xx). For example, in northern and montane conifer forests, large fires account for 3% of the fires but 95% of the damage (Agee 1993). Never-the-less, when only average disturbance sizes are available such as for fires in Quebec (Hunter 1993), applying Shugart’s guideline suggests sizes of 39,800 acres in the lakes region and 1,570,300 acres in the remaining lands. Applying the same guidelines to Fahey and Reiners (1981) figures for Maine (150 acres) and New Hampshire (50 acres) suggest size on the order of 7500 and 5000 acres respectively. While it may be useful to multiply these numbers by three to 10 approximate the “4 x the stand-replacing patch” estimates, it is theoretically safer (in my opinion) to locate more precise information or develop the information directly using aerial photos of disturbance events. 2a2) Scaling factor 2: Coarse-filter Functions The second scaling factor addresses the role of communities as “coarse-filters” for all associated species particularly those dependent on interior forest habitat. Without a complete inventory and assessment of each species, conservation of the majority of common and uncommon species depends on carefully selecting those community occurrences most likely to contain a full, breeding, complement of their associated flora and fauna (mammals, birds, herptiles, fish, and invertebrates). The approach to developing this scaling factor for matrix-forming communities was to first identify a set of species typical of, or restricted to, a particular community in the ecoregion. Initial attempts to develop this list, however, revealed that most vertebrates and many invertebrate species utilize a mix of matrix and patch community types within a certain proximity to meet all their resource needs. An important consideration then, was those species requiring or associated with forest interior habitat for breeding purposes, as these species have the most restrictive requirements with regard to forest size and some are area-sensitive (Martin and Finch 1995). The analysis was restricted to birds and mammals as they are usually the most space-demanding and wide-ranging. Subsequently, available information on the size of breeding territories, special habitat requirements, and home range was used to determine the minimum area requirements for the community type. In scaling the occurrences towards this component of the fauna we assumed that the space requirements of smaller species would be met as well (certain insects or amphibians may have additional condition requirements). Forest bird assemblages. An estimated 127 species of birds preferentially utilize the four matrixforming forest types in the Northern Appalachian ecoregion (De Graff and Rudis 1986). Thirty-three species are closely associated with coniferous spruce-fir forest while 32 others are closely associated with deciduous northern hardwood forests. The effects of forest patch size and forest fragmentation on particular species, especially neotropical migratory songbirds has received extensive attention in the literature. (Robbins et al. 1989, Gentry 1989, Gibbs and Faaborg 1990, Villard et al. 1993, Ziehmer 1993, Van horn et al. 1995, Gale et al. 11 1997, Burke and Nol 1998). A variety of mechanisms have been proposed and tested to account for the diversity and abundance differences between large and small forest tracts. Breeding success (e.g., the ability of a female bird to successfully fledge young) is repeatedly cited as a likely critical function that is positively associated with forest patch size. Mechanisms that account for low breeding success in smaller patches include: reduced pairing success, (Gentry 1989, Gibbs and Faaborg 1990, Villard et al. 1993, Ziehmer 1993, Van horn et al. 1995), inadequate foraging or nesting sites (Burke and Nol 1998), increased competition for resources (Ambuel and Temple 1983,), increased nest predation (reviews in Paton 1994 and Hartley and Hunter 1997), and increased nest parasitism (Brittingham and Temple 1983). Additionally, several of these factors interact to create negative feedback cycles. For example, the effects of predation may be amplified if food resources are low and restricts a nesting pair from beginning a second brood (Burke and Nol 1998). In general, Helle (1985,1986) concluded that cavity-nesting, non migratory species were particularly sensitive to fragmentation, while Hunter (1992) concluded that sedentary stereotypic species preferring large tracts of old forests were the most sensitive to habitat loss. In the Northern Appalachians the former would likely include Barred Owls (Strix varia) that prefer deep woods with large cavity trees. This species has an average breeding territory of 550 to 650 acres (Nicholls and Warner 1972, Stokes 1989). An example of the latter would include Northern Goshawk (Accipiter gentilis - nesting females utilize a 960 acre territory, Stokes 1989), Spruce Grouse (Dendragapus canadensis -- nesting females utilize a 247-370 acre territory; Ellison 1933, Fritz 1977) and Red Crossbill (Loxia curvirostra -- defends a small area around the nest; Lawrence 1949). Additionally many shrub and ground-nesting songbirds have been identified as “area sensitive” as they are typically absent from smaller forest fragments. Freemark et al. (1996) compiled a list of area-sensitive species that contains 22 species found in the Northern Appalachians. These include: Hermit Thrush (Catharus guttatus), Black-and-white Warbler (Mniotilta varia), Canada Warbler (Wilsonia canadensis), Mourning Warbler (Oporornis philadelphia), Northern Parula (Parula americana), Northern Waterthrush (Seiurus noveboracensis), Black-billed Cuckoo (Coccyzus erythropthalmus), Yellow-billed Cuckoo (Coccyzus americanus), Hairy Woodpecker (Picoides villosus), Eastern Wood-Peewee (Contopus virens), Least Flycatcher (Empidonax minimus), Whitebreasted Nuthatch (Sitta carolinensis), Veery (Catharus fuscescens), Wood Thrush (Hylocichla mustelina), 12 Black-throated Blue Warbler (Dendroica caerulescens), American Redstart (Setophaga ruticilla), Ovenbird (Seiurus aurocapillus), Scarlet Tanager (Piranga olivacea), Red-shouldered Hawk (Buteo lineatus), Magnolia Warbler (Dendroica magnolia), and Blackburnian Warbler (Denroica fusca). Robbins (1989) analyzed 14 area-sensitive species in the moderately well-forested region of western Maryland and determined that 3000 ha (7413 acres) was the minimum reserve size that would retain all species. Askins found similar patterns in southern Connecticut (Askins et al. 1987) a region he considered roughly similar to Robbins’ study area with regard to forest cover (Askins pers. comm.). As the objective of the critical size criteria was to identify source breeding areas that will provide long term habitat for hundreds of breeding pairs, we adopted the recommendations of Robbins et al. (1989) for core reserve areas of at least 10,000 acres for forest dwelling neotropical songbirds(assuming it takes a 10K block to get 7413 acres of core area with a 200 meter road buffer). Mammal assemblages. An estimated 51 mammals are typical of the Northern Appalachian ecoregion forest types (DeGraff and Rudis 1986). Relationships between forest community types and mammal species are not well understood, especially for small mammals such as moles, shrews, bats, and voles. For larger mammals, 15 are closely associated with the matrix forest types(DeGraff and Rudis 1986). Several mammals require remote, extensive, mature forest tracts. Many require mature trees or standing dead snags and cavities (Table 1.2). One, the marten (Martes americana), has been cited as an old growth specialist (Bissonette 1991) as it benefits from the presence of downed wood and coarse woody debris (Buskirk 1992). As with birds, we examined the size and condition needs of some of the more restrictive species to determine the size of the forested reserves needed to insure adequate breeding and source populations. Using the marten as a gauge, Bissonette estimated that 128,741 acres (521 km2) of mature/old growth forest in western Newfoundland could support 150 resident martens (using a mean female home range of 1641 acres –see below) with a presumably smaller effective breeding population. (add Danielsons work). To estimate area needs for mammals we compiled the mean female home range acreage for a variety of Northern Appalachian mammals (Table 1.2) using the generalization that female mammals typically establish and utilize mutually exclusive territories during the breeding season. To address the actual size needed for a community occurrence to be a source area for breeding for both birds and mammals (exclusive of neotropical forest birds) we multiplied the mean breeding territory or 13 female home range by 25 to reflect the so- called “50/500” rule (Franklin 1980, Soule 1980). The 50/500 rule suggests that at least 50 genetically-effective individuals are necessary to conserve genetic diversity within a metapopulation over several generations. While use of this guideline, has been widely critiqued as misleading and inappropriate for all species under all circumstances (refs), it still stands as a reasonable order-of-magnitude estimate of minimum numbers needed for a genetically effective local population (Lande 1988, Meffe and Carroll 1994). Adopting this guideline assumed that all of the available habitat was suitable for breeding, and that the reserve was semi-isolated. None of these assumptions is very realistic but we are not advocating for an actual population size of 50 individuals, rather just approximating the area needed to accommodate 25 breeding females. 125K lynx (Felis lynx) 3200-7900 80K fisher (Martes pennanti) 3000-5000 moose (Alces alces) 2000-10000 marten (Martes americana) 1200-6000 75K 50K 30K white-tailed deer (Odoceoileus virginianus) gray fox (Urocyon cinereoargenteus) Porcupine (Erethizon dorsatum) Woodland jumping mouse (Napaeosapus insignis) deer mouse (Peromyscus maniculatus) red squirrel (Tamiasciurus hudsonicus) Meadow jumping mouse (Zapus hudsonius) s. red backed vole (Clethrionomys gapperi) n. flying squirrel (Glaucomys sabrinus) black bear (Ursus americanus) 25K 1000-2000 200-500 2 Hemlock 5000-20000 Special habitat requirements Spruce-fir bobcat (Felis rufus) N. Hardwood Female Home Range (acres) 25 x mean (in 1000’s of acres) Name Aspenbirch Table 1.2. Characteristic mammals associated with matrix forest types in the Northern Appalachian ecoregion, arranged in order of decreasing home range (based on DeGraff and Rudis 1986). Sources of the rounded range estimates are given in Anderson 1999. 2 2 2 2 Rock ledges, windthrows, hollow logs Secluded den sites, extensive forest Hollow trees logs Wetlands 2 Prefers undisturbed stands, hollow trees, logs Softwood yarding cover 2 2 2 Hollow logs, tree cavities, crevices 2 Rock ledges, den trees 2 2 2 2 2 5K 2 6-36 0.1K 2 1-7 0.02K 1-2 0.02K 2 1 0.02K 2 0.30-1.0 0.01K 0.25-0.50 0.01K 2 2 ? ? 2 2 ? ? 2 2 2 14 2 2 Moist cool woodlands, loose soils, herbs 2 Woodland with mature trees, conifers preferred Moist woodlands, loose soils, herbs 2 Springs, brooks, bogs Mature woodlands w/cavity trees Primarily in remote forests and swamps, fallen trees, hollow logs, rock ledges 2a3 Synthesis of the Disturbance and Coarse-Filter Scaling Factors To set a critical size threshold for matrix forest communities, we combined the two scaling factors along a single linear axis (Figure 2a.4). This allows an estimate of the effect of any particular size minimum on a variety of selected disturbances and faunal associates. For instance, an occurrence of 25,000 acres should be effective for 1) absorbing all types of expected severe wind and fire disturbances, 2) containing multiple breeding populations of all forest interior songbirds, and 3) containing 25 female territories of Barred Owl, Spruce Grouse, and Northern Goshawk and 21 female territories of marten. That size covers the bulk of the forest-interior requiring species. Theoretically, an occurrence of 25,000 acres could also contain 5-12 female breeding territories of species that utilize, but are not restricted to interior forest conditions, such as lynx (Felis lynx), bobcat (Felis rufus) and fisher (Martes pennanti), that are shown on the right side of figure 2a.4. If the size was expanded to 125,000 acres it could theoretically contain 25 of all the latter mammals and would perhaps be more effective at absorbing very rare extensive fires in far northern spruce-fir forests. A reserve size of 500,000 acres would be large enough for 25 resident female mountain lions (Felis concolor) (which are unconfirmed for the region at this time). Based on the above logic and information, we set the criteria for minimum size of a viable matrix forest occurrences at 25,000 acres. One of the implications of this minimum is that species that demand more space than 25,000 acres may need their own fine-filter plans analogous to the rare species sites. This same approach was used in other Northeast and east division ecoregions (Fig 2a.5). Figure 2a.5) Scaling factors for Matrix Forest in the Central Appalachian 15 Scaling factors and Reserve size for Matrix forests in the Central Appalachian Ecoregion: Fires (NH & TH) DISTURBANCES (4 X's the historic severe-destruction patch size) M. Anderson 1999 Downbursts Hurricanes Black Bear Tornados Fires (Oak)* SPECIES (25 X's the mean female home range) Barred Owl Broad-winged Hawk Bobcat Neotropical birds 0 2 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40 // 75 // 150 Reserve size in 1000s of acres Factors to the left of the arrow should be encompassed by a 25,000 acre reserve NH = N. hardwoods (Maple-Beech-Birch) TH = Transitional Hardwoods (High elevation Red Oak or Red Oak -Sugar Maple) * Oak forests are dependent on relatively high-frequency, moderate fires, info on catastrophic fires is sketchy Neotropical estimates based on Robbins et al. 1989, see text for full explanation. 16 A similar approach may be used to determine viability criteria for large patch (black spruce peatland) and small patch (calcareous cliffs) systems (Figures 2a.6 and 2a.7 below) Size relationships of black spruce/dwarf shrub peatland complexes in the Northern Appalachian ecoregion. SIZE COMPARISONS (for the NAP ecoregion based on known occurrences) SPECIES (25 X's the mean female home range) * Small Fires mode median Marion Bog average largest Bog lemming Ringed-neck duck Water shrew Yellow-bellied flycatcher Masked shrew Olive-sided flycatcher jutta arctic bog elvin Palm warbler bog lesser fritillary Wilsons warbler purple lesser fritillary Lincoln sparrow marsh ground cricket 0 2 5 25 50 100 500 Rusty blackbird 1000 // 2000 Size in acres Factors to the left of the arrow should be encompassed reserve of that size Peatlands accumulate peat and close at the rate of 2 to 20 cm per 100 years (Mitch and Gosslink 1986) *Based on examination of time-sequence airphotos they may close at about 0.25 acre per year during dry years, many have been stable for 3000-4000 years (Crum 1998) Ave block size = 13,170 acres, mode = 8092, median = 2799 Scaling factors and size relationships of calcareous cliffs in the Northern Appalachian ecoregion. SIZE (for the NAP ecoregion based on known occurrences) Exfoliating Rock Slabs mode 1 average 16 SPECIES largest 75 Ferns: Maidenhair spleenwort, Fragrant woodfern, rock-selaginaella, slender cliffbrake etc. Herbs: scirpus-like sedge, ebony sedge, birdseye primrose, early saxifrage, lyre-leaved rockcress etc. (500 individuals) 0 50 100 250 Size in acres Factors to the left of the arrow should be encompassed reserve of that size Many known occurrences have remained for over 100 years based on historical records Restricted invertebrates unknown 17 500 // 2000 2b) Condition Criteria Identifying reliable indicators of ecosystem condition is still in its early stages but has been identified as a high priority task by several ecologists (Odum 1985, Waring 1987, Rapport 1989, Ritters et al. 1992). As a practical approach, measuring the current condition of an occurrence may be partitioned into two parts: 1) an assessment of negative anthropogenic degradation or evidence of stress due to alteration of landscape processes, and 2) positive evidence of biological legacies or historical continuity. The former attributes may be developed into guidelines for conservation action with respect to what features need to be removed, repaired or prevented. The latter attributes may serve as restoration guidelines for which attributes need to be restored and replenished . Together they may serve as a road map for determining management options. 2b1) Negative Impacts: Stress, Fragmentation and Roads. Assessing anthropogenic impacts such as fragmentation, alteration of natural disturbance regimes, introduction of exotic species, selective species removal, and modifications of air or water chemistry has direct relevance to occurrence viability. The detection and interpretation of these changes, however, ranges from very difficult to patently obvious (see attached document Mapping the 5 s’s). Direct symptoms of stress on a community include changes in species diversity, nutrient cycling, productivity, size of the dominant species, and a shift in species dominance to opportunistic short-lived forms (Rapport et al. 1985). A depauperate species composition relative to the typical composition (e.g., an absence of characteristic but uncommon species) or poor development of vegetation structure relative to the typical structure may also indicate stress on a community (Natural Heritage ecologists, pers. com.). The latter features suggest that the occurrence may have been recently disturbed, or that the landscape processes are in flux or not operating. Additional evidence of stress includes overcrowding of the dominant species, little evidence of regeneration, regeneration that differs from the current composition, or a noticeable component of exotic species or species indicative of other conditions. The recognition that most of the features listed above require contrasts to be made against some type of benchmark condition has inspired a body of literature on the importance of “reference sites” (refs). As a general rule, a well-developed structure and a species composition that includes the presence of characteristic but uncommon species implies good quality habitat, some historical persistence, and therefore suggests a greater probability of future integrity. 18 Of the more obvious sources of stress, fragmentation, is one of the most easy and critical to detect in that it is often associated with many other negative effects. A key factor in measuring the fragmentation of a community occurrence, is the judgment of which features—highways, dirt roads, power lines, railroads, trails—reduce the integrity of the system to an unacceptable degree, and which do not (Forman and Alexander1998). All such features may have detrimental effects on at least some species and some populations. Thus, fragmenting features have the cumulative effect (Forman 1995). Arguably the most widespread and insidious of fragmenting features in the East and Northeast are roads. Forman (1995) suggests that roads are a particular type of linear “edge” corridor, which subdivide an otherwise homogenous area into smaller areas but of themselves do not constitute large areas of contrasting habitat. In forested regions, they may be thought of as a trough corridors as they are generally bordered by vegetation lower than the adjacent areas (Forman 1995). Their effect on the surrounding forest can be divided into two parts: barriers which include their role as semi-permeable filters and sinks for certain species and conduits which emphasize their role in allowing access for predators or exotic species into interior areas. Roads as barriers: The degree to which a road acts as a selective barrier to species is a function of its width, surface material (contrast), traffic volume, and connectivity, and also of the size, mobility, and behavior of the species in question (Forman and Alexander 1998, Fig 2b.1). Beetles and adult spiders rarely if ever cross 2-lane roads and even narrow, unpaved, roads closed to public access may serve as a barrier (Mader 1984, Mader et al. 1988). Chipmunks, red squirrel, meadow vole, and white-footed mouse rarely venture across 15-30 m roadways but readily traverse smaller roads (Oxley et al. 1974). Amphibians may also exhibit reduced movement across roads (Hodson 1966, van Gelder 1973, Langton 1989, ? and Hunter 1999). Mid-size mammals such as skunks, woodchuck, raccoon and eastern gray squirrel will traverse roads up to 30 m wide but rarely ones over 100 m (Oxley et al. 1974). Larger ungulates will cross most roads, but movement across roads is lower than within the adjacent habitat and many species tend to avoid roaded areas (Klien 1971, Singer 1978, Rost and Baily 1979, Singer and Doherty 1985, Curatolo and Murphy 1986). The frequency of black bear road crossings is related to traffic volume (Brody and Pelton 1989). A variety of nesting birds tend to avoid the vicinity of roads (Ferris 1979, van der Zande et al. 1980, 19 Reijnen et al.1987, Forman and Deblinger 1998, Figure 2b.2). Presumably, roads separating home ranges tend to produce subpopulations with differential gene flow (Meffe and Carroll 1994). Forman (1995) suggests that roads may be usefully conceived of as semipermeable membranes (analogous to cell membranes) that are a barrier to some moving objects, a partial barrier to others, and permeable to others. Thus, roads may best be thought of as selective filters that have a cumulative effect as a filter for certain species. Species that are naturally rare, have low fecundity, are slow to recover from a disturbance, are poor dispersers, or are wide ranging are particularly affected by road densities (Meffe and Carroll 1994). Direct road mortality may have significant effects on slowly reproducing mammals (e.g., black bear, panther), herptiles (e.g., turtles), or on rare species. Although over one million vertebrates per day in the U.S. are killed by direct vehicle collisions, the effects on most species are largely unknown and some ecologists suggest they are unlikely to be significant for many species populations (Forman 1995). Roads as conduits: More problematic is the function of roads as conduits that allow access into the interior regions of a forested tract, and brings with it a direct decrease in forest interior area (Fig 2b.3 and Map 2a.1 in Mapping the 5 S’s). Small, unpaved roads with few vehicles are used for movement by ground predators (fox, coyote, wolves), herbivores, bats, and birds (especially crows and jays; Forman 1995). For forest dwelling birds it is likely that high road densities are accompanied by increases in nest predation (Paton 1994, Hartley and Hunter 1997) and nest parasitism (Brittingham and Temple 1983), subsequent inadequate nesting sites (Burke and Nol 1998), and increased competition for resources (Ambuel and Temple 1983). Presumably, the conduit function is not tightly associated with road size or surface as larger roads tend to have more “roadside” region that may be utilized like a small-unpaved road. Roadside open areas are well-documented conduits for certain (often exotic) plants (Verkaar 1988, Wilcox and Murphy 1989, Panetta and Hopkins 1992) and small mammals (Huey 1941, Getz et al. 1978). Moreover, road networks are one of the single best predictors of certain exotic species distributions such as purple loosestrife (Sharkey 19?). Roads are also conduits for dust, chemical pollutants, salt, sand and noise. Traffic noise, in particular, may be primary cause of avoidance of roads by interior-breeding species (Ferris 1979, van der Zande et al. 1980, Forman and ? 2000). Although powerlines share some of the same features as low use roads, the filter 20 and barrier effects may be softened if they are allowed to obtain a shrub cover and the conduit effects appear to be reduced also (Schreiber and Graves 1977, Chasko and Gates 1982, Gates 1991). 2b1) Positive Condition Attributes: Biological Legacies Over time, sites and occurrences develop and accumulate a number of positive features that greatly increase their viability and their contributions to biodiversity. Perry (1994) defines these “biological legacies” as any thing of biological origin that persists and through its persistence helps maintain ecosystems and landscapes on a given trajectory. In forests, biological legacies include the presence of fallen logs and rotting wood, a well developed moss and herbaceous understory, structural complexity in the canopy and understory layers, a reservoir of soil organic matter for nutrient storage, intact mycorrhizal relationships, seed banks, intact nutrient cycles, and the presence of keystone species (Harmon et al 1986, Tyrrell and Crow 1994, Fig 2b.4). The development of many of these features, may take many generations and sometimes hundreds of years to develop (Duffy and Meier 1992). As few current restoration efforts can guarantee success over such long time frames, it is crucial to identify and target community examples for conservation that appear to have the greatest biological legacy. Additionally it is important to set goals for restoration and management regimes that aim to restore and replenish legacy features. Biological Legacies and Resistance / Resilience: The presence and persistence of biological legacies has a large positive effect on the resistance and resilience of a community occurrence. For instance in undisturbed old forests, large volumes of water are stored in accumulated litter and downed logs. This, in turn, reduces the severity and redistributes the consequences of catastrophic fires through increasing the patchiness of fire effects and providing direct refuges for salamanders, fungi and other organisms. The enormous buffering effect of legacies were observed even in the extreme example of lava flows after the eruption of Mount St. Helens. To the surprise of many ecologists the initial recovery of that system was largely a function of remaining biological legacies (Franklin et al. 1985). In the East, “young forests” which develop after natural disturbances often retain a large amount of the existing legacies in contrast to “harvested forests” where many of the legacies are removed or destroyed (Hansen et al 1991). Thus although disturbance removes and transforms biomass, the residual biotic legacies influence stand recovery to the point that most disturbances may be viewed as converting resources from one state to 21 another rather than “wiping the slate clean: (Perry 1994). In their transformed state, resources that were previously “locked up” become available for utilization by new sets of species. Some biological legacies may even function to increase particular disturbances. For example, volatile oils in scrub oak (Quercus illicifolia) leaves, and many heath family plants (ericaceae) serve to increase the fires frequency and severity in pine-barren systems where some of the dominant species are dependent on fire for dispersal of propagules and the recruitment of new individuals (Forman 1979). Legacies play a critical role in patch communities as well. For example, emergent marshes accumulate persistent dead organic matter which stores water and nutrients and serves as critical substrate for nutrient transformations (Mitch and Gosslink 1986). Like forests, the build up of organic debris, seed banks, storage organs, organic mats, diverse phytoplankton, invertebrate and pollinator populations and complex food webs accumulate to create structure and diversity which leads to an increase in the stability of the marsh system over time. Mitch and Gosslink (1986) suggest that a theme common to all wetlands is that ecosystem development insulates the system from its direct environment primarily through peat production that stabilizes the flooding regime and shifts the main source of nutrients to recycled material within the ecosystem. Biological Legacies and Species Richness: Biotic legacies also have a large effect on the density and richness of associated species (Fig. 2b5). Insects such as the ant-like litter beetles (family Pselaphidae, order Coleoptera) are both more abundant and richer in species in old-growth forests in New Hampshire (Chandler 1986). This is largely explained by their association with rotten wood and deep leaf litter, both of which are more abundant in old-growth forests (Chandler 1986). Likewise, breeding bird densities are significantly higher in old growth hemlock hardwood forests when contrasted with similar forest types managed for timber production (Haney and Schaadt 1996). The magnitude of the differences in Haney and Schaats (1996) research were impressive, ranging from two or three times as abundant in old-growth for brown creepers and black-throated green warblers to over 40 times more abundant in old-growth for Blackburnian warblers and magnolia warblers. The authors believed these differences to be explained mostly by differences in forest structure such as snag size and density but it may reflect the presence of richer and more diverse food resources as well (Goodrum et al. 1971, Burke and Nol 1998). Additionally, breeding individuals often return to the same forest stand, year after year, demonstrating a historical 22 connection to a particular system at a particular place (Levianthal 1999, Eastman 1999). Epiphitic lichen floras, have been found to be richer and denser in Northern Appalachian old-growth forests with over 30 species being proposed as exclusive indicators of old-growth conditions (Selva 1996). The effects of oldgrowth conditions on mammals has not been well studied although Pelton (1996) has argued that many carnivore species in the east benefit from forest components associated with old-growth characteristics (e.g. tip-up mounds, snags, rotted tree cavities). At least one study has suggested that the lynx population in northern Maine may be limited by a lack of large snags (ref). The presence or absent of certain individual species (harmful exotics or keystone species) may have a large effect on the viability of a community. Exotic species are often associated with anthropogenic disturbances particularly roads and trails and are usually a reliable indicator of past history. Caution is necessary in interpreting the effects of exotics because, as a group, they do not share many characteristics. Some types of exotics may have little effect on a system, others may cause large amounts of degradation, some produce apparent changes which dampen out over time and many produce both losses and gains (Anderson 1992). Likewise the absence of keystone species may cause a number of subtle changes that are hard to evaluate and interpret Biological Legacies and Source-Area Characteristics Because of the problems with determining “source-areas” based on long term measurements of species demographic parameters (discussed previously under “size’) it is only practical to determine the physical characteristics of source-areas that insure reproductive success of multiple species over time (Fig 2b6, e.g. food, breeding/nesting or establishment sites, “safe” site and limited predator access, critical biotic interrelationships such as micorrhizal fungi or pollinator asssociations). Legacy features that can be measured and quantified during field surveys are particularly useful in determining the likely-hood of an area serving as a source area for certain species. 2b3) Quantifying Biological Legacies: Coarse Woody Debris Convincing examples of how legacies contribute to source area characteristics have been most extensively studied with regard to old logs and snags collectively referred to as coarse woody debris (CWD) in forests (see Harmon et al.19xx for a review). A typical unmanaged forest receives two major inputs of CWD (Fig 2b7). The first occurs in the initial 80 or so years of forest development when many young trees die from shading or other competitive processes, the second when very old trees die (Harmon 23 et al.19xx). These two fluxes differ in their qualities with the latter being of considerable more utility to the associated species due to its persistence time, storage capacity and size and types of substrates it provides (ref). In old intact sites these age related processes become spatially stirred as the area become a mix of ages and debris inputs. The contributions of CWD to specific species have been documented for plants, invertebrates and vertebrates. For plants, CWD provides important regeneration sites. McKee found that 94-98% of the tree seedlings in certain pacific northwest forest sites were on CWD which, comprised only 6-11% of the available substrate. In the Adirondacks, Knechtel (1903) noted that reproduction of white pine, red spruce and eastern hemlock occurred almost entirely on fallen, decaying logs. These old moss-covered “nurse logs” tend to develop only on large fallen trunks as smaller trunks decay too rapidly for moss colonization to occur (Wessles 1999). While many young trees may not survive to maturity, canopy trees growing on old decayed logs is well documented for birches, balsam fir, red spruce and eastern hemlock (ref). Invertebrates diversity and density benefit from CWD. Large numbers of insects representing at least 14 families utilize CWD for food, shelter and breeding substrate (Harmon et al 199X, table x). Many of these insects are specific to particular tree species, to a particular stage of the decomposition process (dying, dead, decaying) and to a particular part of the tree (heartwood, inner bark etc.). Species more characteristic of the litter fauna, such as slugs, snails, terrestrial isopods, centipedes and earthworms will migrate into CWD during hot weather (Lloyd 1963). Some species such as the ant-like litter beetles (family Pselaphidae, order Coleoptera) are both more abundant and richer in species in old-growth forests (Chandler 1986). Table X. Major invertebrate families associated with coarse woody debris (Harmon et.al. 199x) MAJOR TAXA GROUP Bark beetles Wood borers Termites Carpenter ants Wasps and Bees Butterflies and Moths MAJOR FAMILIES Scolytidae Platypodidae Bruprestidae Caramycidaea Curculividae Isoptera (order) Camponotus Syricidaea Xylocadidae Other predaceous families Hepialidae Cossidae 24 EXAMPLE Bark beetles Ambrosia beetles Flat headed wood borer Round headed wood borer Weevils Termites Carpenter ants Horntail wasps Carpenter bees Various Larva bore into wood Larva bore into wood Beetles Flies (parts of 45 families) Mites Sessidae Pselaphidae Tipulidae Xylophagidaea Steganacarus Larva bore into wood Ant-like litter beetles Crane flies Fungus gnats Many others Vertebrates also selectively utilize CWD particularly logs and standing snag for shelter and breeding sites (Fig. 2b8). Some, like the woodpeckers, are primary excavators while most use cavities excavated by other species. Of the 127 bird species associated with matrix forest types in the northern Appalachians, 21 require cavities (Anderson 1999, Degraff and Rudis 1986). Likewise at least 7 of the mammals associated with matrix forest utilize and benefit from fallen logs and standing snags. These include lynx , bobcat, grey fox, northern flying squirrel, fisher, marten and black bear. Herptiles are particularly dependent on CWD, especially fallen moisture-retaining logs, for shelter (list types and examples) . As sites accumulate legacies over time they tend to become more complex in structure and biotic interrelationships as well as developing resource pools that buffer them against disturbance events (refs). The development of vegetation structure creates a wider variety of microsites that in turn create more breeding and shelter sites. For example consider the nesting preferences of the 127 bird species associated with matrix forest in the northern Appalachians, 64 build cup-type nests in trees, shrubs, or hidden ground locations; 21 require cavities; 11 build platforms in treetops; 4 construct pendulous nests; and 5 nest on simple ground scrapes. Others nest in banks, crevices, cliffs, and under bark. Additionally 16 species typically nest in conifer branches; 12 in deciduous trees; 15 in tall or dense shrubs; 13 on the ground, and 12 utilize old snags. The range and variation in nesting behaviors emphasize the importance of structural and compositional diversity in forests. The combined features of vegetation structure and CWD amounts may begin to explain why Haney and Schaats (1996) found that old growth patches were so much denser in breeding birds than managed forests. Recent research by Burke and Nols (199x) and Hagen (1998) suggest that food resources may be more important that nesting substrates. Predator access as discussed previously is also closely intertwined with breeding success. Setting quantitative goals for coarse woody debris In terms of practical conservation there remains the question of how much of each biotic legacy, such as CWD, is necessary to insure that a site 25 both retains its resistance/resilience and functions as a source area for breeding species. First approximations may be estimated by examining existing old growth sites and replicating their structure. Figure 2b8 and Table 2 below provides some quantitative benchmarks for CWD in eastern northern hardwood forest provided by McGee et al. (1999), who examined the issue at several Adirondack sites as well as across 23 other literature sources. Example criteria for legacies in a Northern Hardwood forest (adapted from McGee et al.1999) FEATURE Living trees Standing dead Downed logs TOTAL AMOUNT SIZE DISTRIBUTION Number per ha <25cm DBH 275 22 (0-50) 44 (10-39) 32% 400 60 (35-80) 137 110m3/ha 25-50cm DBH 75 19 (10-40) 70 (48-96) 51% >50cm DBH 50 (9 >70) 18 (10-25) 23 (5-34) 17% Unlike the attribute of size, condition and legacies requires long time frames to develop and thus have large implications to land based conservation. Consider, for example, the length of time it may take to develop 9 fallen logs, each over 50cm DBH, per acre of land in a 30 year old Northern Hardwood forest. Although there may be ways to speed up or augment the development of legacies (Spies et al. 1991) it is probably more economical and strategic to locate those community occurrences with continuity and focus reserve development around them. In the East and Northeast, where the options are limited, both identifying the best areas and restoring them to a higher condition appear to be critical needs if we are to succeed in meeting our objectives. Identifying community examples which had historical continuity was important the ecoregional planning criteria. Unfortunately current condition is presently difficult to evaluate without actual site visits. For matrix sites we used an extensive GIS analysis of road density, landcover and other features supplement by a expert-interview questionnaire examining the historical and current uses, and condition of a potential matrix site. For patch communities, we opted for EO ranks and expert interview. AN example of the expert interview reports as well as a discussion of the need for more extensive ground surveys and mapping is discussed in the accompanying document Mapping the 5 S’s. 26 Initial steps and future condition I would like to generate some discussion on this topic at the March 21st meeting. I am including a few figures (2b9-2b12) and the following paragraph that I threw into the Mapping the 5s document: Viability, as defined by the resistance and resilience of a system over time is a dynamic state that reflects the interaction of a system with disturbances and stress. Upgrading critical condition attributes of the system such as restoring biological legacies, limiting or removing fragmenting features and restoring a clean, free-flowing stream/lake network will help the system maintain itself along a given trajectory by increasing its resistance and resilience (Fig 2b.9 – 2b.12). However, given a scenario of rapid climate change, shifts in species distributions and increased disturbances, the map of long term conservation success for a site is not a known entity such as a specific species composition or a particular proportion of current community types (Gilpin 1983). Rather the spatial data presented here may be used to develop scenarios and quantitative models that test how a viable functioning system might respond to changes. ELUs and their component parts represent the most stable features and can be adapted to model how fire, wind, flooding might be distributed across the landscape. Trombulak (1996) in an essay on the restoration of old growth forests offers the following six guidelines: 1) Plan restoration at the landscape level rather than the stand level (the 15 to 25K minimums suggested in this document meet Trombulak’s idea of landscape level) 2) Don’t aim for a specific set of species as an end point. 3) Plan for the long term (centuries) 4) Aim to restore all old growth characteristics not just a subset 5) Deal with environmental stresses that influence species composition, succession and ecosystem processes (populations of large herbivores, populations of pests and pathogens, fire suppression, invasion by exotic species) 6) Plan for compatible uses of forests that are in the process of being restored to old growth. 2c) Landscape Context Forest Management Workshop April 4-6 Connectivity Working Group June 11-12 27 Issues of larger landscape condition, roles of forest management, natural dynamic forestry, wide ranging species and other topics pertaining to the space between the forest matrix blocks will be discussed by the above groups and not developed here. Acknowledgements All or parts of this document benefited from review and comment from the following people: Jean Andersen, Kim Babbitt, Rodney Bartgis, Henry Barbour, Ashton Berdine, Frank Biasi, Patrick Bourgeron, Bill Brown, Steve Buttrick, Connie Carpenter, Pat Comer, Frank Davis, Tony Davis, Bob Eckert, Don Faber-Langendoen, Charle Ferree, Jean Fike, Sue Gawler, Denny Grossman, Craig Groves, Tina Hall, Lise Hanners, David Hunt, Mac Hunter, Deborah Jensen, Greg Kehm, Tom Lee, Greg Low, Frank Lowenstein, Julie Lundgren, Arlene Olivero, Karen Poiani, Dave Mehlmen, Mike Merrill, Ken Metzler, Reed Noss, Cathy Regan, Marian Reid, Carol Reschke, John Roe, Josh Royte, Ana Ruesink, Doug Samson, Mike Schafale, Rick Schneider, Loring Schwarz, Mark Shaffer, Marie-Lousie Smith, Lesley Sneddon, Eric Sorenson, Dan Sperduto, Mike Stevens, Pat Swain, Jim Taylor, Elizabeth Thompson, Jim Thorn, Bill Toomey, Jeff Wagner, Dean Walton, Barbara Vickery, Alan Weakley, Susan Young and Bob Zaremba. 28