* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Title - HHBElectiveOutline

Survey

Document related concepts

Radio propaganda wikipedia , lookup

Architectural propaganda wikipedia , lookup

Propaganda in the Soviet Union wikipedia , lookup

Propaganda of the deed wikipedia , lookup

Psychological warfare wikipedia , lookup

Role of music in World War II wikipedia , lookup

Transcript

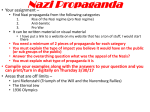

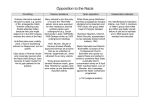

Section 7: Conformity and Obedience page 1 Section 7: Conformity and Obedience Section at-a-glance The purpose of this section is to explore essential questions such as: ? What is “the media?” What purposes does it serve? How does the media shape the way we think and act? ? What is propaganda? How can propaganda be distinguished from other forms of media? ? How do you know when information is accurate? Under what conditions do you believe what you see and hear? ? What type of schooling prepares young people for their role as citizens in a democracy? What type of schooling prepares young people for their role as citizens in a dictatorship? ? What is dehumanization? What conditions allow a group to become dehumanized? ? What is the difference between obedience and unconditional (“blind”) obedience? What can be the consequences of unconditional obedience? ? Under what conditions is it appropriate to obey authority? Under what conditions is it appropriate to resist authority? When exploring these questions, students will deepen their understanding of concepts such as: Antisemitism Propaganda Censorship Dehumanization Civic education Conformity Obedience Resistance Opportunism Fear Terms introduced in this section include: Hitler Youth The lesson ideas for this section are built around these core resources: “The Nazis: A Warning from History,” episode 2, Chaos and Conspiracy (film) Nazi propaganda posters (image) Obedience (film) Readings from Chapter 5, Facing History and Ourselves: Holocaust and Human Behavior Facing History Elective Course Outline DRAFT – NOT FOR PUBLICATION Section 7: Conformity and Obedience page 2 Part 1: Overview Background information To support the teaching of this section, we strongly recommend reading chapter 5 in the resource book Facing History and Ourselves: Holocaust and Human Behavior. Rationale: What is the purpose of this section? Why teach this material? As we explored in the previous section, once Hitler and the Nazis seized power, they enacted laws that furthered their ideology. For example, they all but ended opposition by banning political parties and they stripped Jews of German citizenship by passing the Nuremberg laws. Most Germans went along. Why? What were the forces that influenced decision-making in Nazi Germany? Historical context and agency are two important concepts that can help to examine decisions made in the past and connections to the present. Understanding historical context requires identifying important events and cultural norms that define an era. Agency is the concept that people are powerful social and political actors whose choices shape history. Considering agency means looking at specific choices made by individuals – children, women and men – why these choices might have been made and what were the consequences. Who had power in Germany during the 1920’s and 30’s? Who did not? What was considered to be acceptable behavior? What was popular? Unpopular? How did people define success? What influential events took place during this time? These are the kinds of questions we ask when describing the historical context of a particular time and place, such as Germany in these decades. Psychological factors also shape decision-making. This section includes resources on two aspects of human behavior that influence how individuals behave in larger society: conformity and obedience. Recall reading about Eve Shalen in “The ‘In Group’,” and the story of “The Bear that Wasn’t”. The need to belong, the desire to “fit in,” the yearning for acceptance, these are powerful forces that encourage individuals to conform to the perceived norms of the larger group. Examining decisions made by children, women and men through the lens of obedience and conformity raises the complicated issue of how ordinary people can behave under certain circumstances. The role of propaganda One way to look at obedience and conformity in Nazi Germany is through the lens of propaganda. Propaganda - the dissemination of information to persuade an audience toward a particular idea or cause - was among the most powerful tools in the Nazi armada. Adolf Hitler said, “By the skillful and sustained use of propaganda, one can make a people see even heaven as hell or an extremely wretched life as paradise.” By establishing the Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda as one of his first acts as chancellor, Hitler demonstrated his Facing History Elective Course Outline DRAFT – NOT FOR PUBLICATION Section 7: Conformity and Obedience page 3 belief that controlling information was as important as controlling the military and the economy. He appointed Josef Goebbels to direct this department. Goebbels’s strategy as Propaganda Minister was guided by the maxim, “If you tell a lie big enough and keep repeating it, people will eventually come to believe it.”1 Goebbels penetrated virtually every sector of German society, from film, radio, posters, and rallies to school textbooks with Nazi propaganda. The Nazis also found ways to remove ideas from larger society that they felt went against party doctrine. They organized public book burnings, censored newspapers, published lists of banned books and authors, and prohibited “offensive” artists from displaying their work (except when displayed by the Nazis under the label of “degenerate” art). Much of Nazi propaganda was aimed at dehumanizing groups that the Nazis saw as “unfit”: the mentally and physically disabled, homosexuals, communists and Gypsies. Jews were especially targeted. The Nazis understood the power of old antisemitic myths and stereotypes that shaped the way ordinary Germans and other Europeans viewed Jews. They combined those lies with the (flawed) theories of race-science to arouse hatred. Then, they created a whole industry to disseminate propaganda that presented Jews as a monstrous threat to humanity and a subhuman source of disease and degeneration. Psychologist Phillip Zimbardo asserts that one reason many Germans were capable of unspeakable acts against Jews and other groups was because they had come to believe that these “sub-humans” were unworthy of dignity, respect, and eventually, life itself.2 The Nazis focused much of its propaganda on the youth. Hitler often spoke of the importance of indoctrinating German youth to Nazi ideals. In a 1935 speech to Nazi party officials, Hitler declared, “He alone, who owns the youth, gains the future,”3 and four years later he announced, “I am beginning with the young. . . . With them I can make a new world.”4 One of the critical spaces where the Nazis hoped to indoctrinate German youth was in the schools. Recalling his experience as a student in Nazi Germany, Alfons Heck shares: Unlike our elders, we children of the 1930s had never known a Germany without Nazis. From our very first year in the Volksschule or elementary school, we received daily doses of Nazism. These we swallowed as naturally as our morning milk. Never did we question what our teachers said. We simply believed what was crammed into us. And never for a moment did we doubt how fortunate we were to live in a country with such a promising future.5 German youth were explicitly taught to believe that Jews were less-than-human. The teaching of race science in all subjects became mandatory. In the film, Childhood Memories, Holocaust survivor Frank S. recalls how he was forced to stand in front of his class as the teacher instructed students that Aryans were strong and Jews were weak. Another German-Jewish 1 D-M http://www.lucifereffect.com/dehumanization.htm 3 DM 4 DM 2 5 Facing History Elective Course Outline DRAFT – NOT FOR PUBLICATION Section 7: Conformity and Obedience page 4 man recalls how lessons in school about the inferiority of Jews translated directly into violence against him: The second year a Nazi functionary was put in place as the principal. And this new principal came into our classroom and made all the Jewish boys and girls stand up – about two or three of us. And then he said that Jews were the source of all the problems in Germany – he said they were enemies of the people. He reiterated the caricatures of Jews [as] money-grubbing [sic]. They will steal your belongings, they’ve been stealing from the country and individuals….I didn’t listen that closely…I didn’t believe it…because I knew my own family…And then he told all the boys in the class that it was patriotic to beat up all the Jewish boys and make them go away…They chased me and caught me and whipped me with these flexible sticks.6 What was the impact of these persistent messages in Germany? Psychologist Philip Zimbardo, writing about the effect of antisemitic propaganda on German youth, argues: Hitler’s “final solution” of genocide of all European Jews began by shaping the beliefs of school children through the reading of assigned texts in which Jews are portrayed in a series of increasingly negative scenarios. At the end of these lessons in civics or geography, we see the “reasonable” discriminatory actions that Germans should take toward Jews. This educational propaganda was intentionally designed to create a dehumanized conception of Jews among students by means of providing them with required texts that were colorful and visually told provocative narratives. Students from primary school through high school read these books.7 These examples, and others that are included in the resource book, speak to the power of education on the beliefs and actions of young people. Many would argue that the role of education in any society is to persuade students to act and think in ways deemed positive by that particular society and to honor its values? In Germany, Jews were deemed to be subhuman. Violence against them was accepted, even encouraged. Thinking about education in Nazi Germany provides an opportunity to consider education in our own communities. What does our society value? How are these values expressed in what we teach in our classrooms and in the ways schools are structured? German children who grew up in the 1930s, such as Hede von Nagel, describe how obedience was a central part of their upbringing and schooling. “Our parents taught us to raise our arms and say, ‘Heil Hitler’ before we said ‘Mama,’” she recalls.8 Students did not call their instructors by the title Lehrer, meaning teacher, but instead they referred to their teachers as Erzieher. “The word [Erzieher] suggests an iron disciplinarian who does not instruct but commands, and whose orders are backed up with force if necessary,” explains Gregor Ziemer, a teacher and journalist who lived in Germany when the Nazis came to power.9 Recalling his own schooling, 6 Denial, p. 39 http://www.lucifereffect.com/dehumanization.htm 8 DM 9 DM Facing History Elective Course Outline DRAFT – NOT FOR PUBLICATION 7 Section 7: Conformity and Obedience page 5 Alfons Heck shares, “Never did we question what our teachers said. We simply believed what was crammed into us.”10 Teachers obeyed authority as well, adjusting their curriculum to the new Nazi frameworks. According to Holocaust scholars Richard Rubenstein and John Roth, teachers were among Hitler’s staunchest supporters. They explain: German school teachers and university professors were not Hitler’s adversaries…Quite the opposite; the teaching profession proved one of the most reliable segments of the population as far as National Socialism was concerned. …Teachers, especially from elementary schools, were by far the largest professional group represented in the party. Altogether almost 97% of them belonged to the Nazi Teachers’ Association, and more than 30% of that number were members of the Nazi Party itself. From such instructors, German boys and girls learned what the Nazis wanted them to know. Hatred of Jews was central in that curriculum.11 Erika Mann, a German who opposed the Nazis, wrote a book called School for Barbarians in which she described how the Nazi propaganda permeated the lives of young Germans: “The German child breathes this air. There is no other condition wherever Nazis are in power; and here in Germany they do rule everywhere, and their supremacy over the German child, as he learns and eats, marches, grows up, breathes, is complete.”12 In addition to receiving Nazi propaganda in schools, all German youth were required by law to participate in the Hitler Youth Movement. Hitler Youth groups started at the age of six. In such groups, said Hitler, “These young people will learn nothing else but how to think German and act German. . . . And they will never be free again, not in their whole lives.”13 Parents could be punished if their children did not regularly attend meetings. By 1939, about 90% of the Aryan children in Germany belonged to Nazi youth groups. In the documentary film Heil Hitler: Confessions of a Hitler Youth. Alfons Heck, a former leader of the Hitler Youth describes his strong desire to follow Hitler’s every command. Watching Alfons share stories about his experience raises many questions about the relationship between propaganda, conformity and obedience: What does Heck say inspired his dedication to Hitler and to being a good Nazi? What has shaped his heart and mind? What about Alfons’ story seems familiar to us? What seems particular to Nazi Germany? What are the factors in society today that may be shaping our students’ values, ideas and behaviors? Are our students as susceptible to believing what they see and hear as Alfons and millions of other German youth were? The resources in this section offer a number of opportunities to think about what it must have been like to grow up in Nazi Germany. Eleanor Ayers, the author of numerous books on Nazi Germany and the Holocaust, including Parallel Journeys, describes the 1930s as, “a terrific time to be young in Germany.” She continues, “If you were a healthy teenager, if you were a patriotic German, if you came from an Aryan (non-Jewish) family, a glorious future was yours. 10 DM DM 12 DM 13 DM 11 Facing History Elective Course Outline DRAFT – NOT FOR PUBLICATION Section 7: Conformity and Obedience page 6 The Nazis promised it.”14 Yet, despite the onslaught of propaganda, not all German adults or young people accepted the Nazis’ ideas. By the late 1930s, a number of teenagers were questioning the system Hitler created. Among them were members of the Edelweiss Pirates, a loose collection of independent gangs in western Germany, and the “Swing Kids,” who used dance and music as a form of resistance.15 And some Germany parents left Germany to avoid putting their children in the position of following Hitler’s orders.16 After World War II was over and evidence of Nazi war crimes were made public through the Nuremberg trials, Heck described his experience growing up in Nazi Germany as “a massive case of child abuse.” In his memoir, A Child of Hitler, he writes about the vulnerability of youth and issues a warning to future generations: The experience of the Hitler Youth in Nazi Germany constitutes a massive case of child abuse. Out of millions of basically innocent children, Hitler and his regime succeeded in creating potential monsters. Could it happen again today? Of course it can. Children are like empty vessels: you can fill them with good, you can fill them with evil; you can fill them with compassion.17 The importance of media literacy The success of Nazi propaganda in influencing the minds and hearts of many Germans, especially German youth, demonstrates the dangers that can befall a society whose citizens are not able to make informed judgments about the media around them. Studying propaganda during the Nazi years provides an opportunity to think about how we educate our young people to look at media and ask questions such as, “Who produced this message and what was their goal?” What messages does society send to youth about acceptable ways to think and act? What role does propaganda and other forms of media have on their lives? What are the consequences for young people today who do not conform to “mainstream” culture? (To be sure, for some youth, especially those that do not conform to conventional gender roles the consequences can be extremely harsh.) How do young people today learn how to analyze or “decode” the messages disseminated over the internet, television, and other media, and critically analyze what the see and hear? Studying Nazi propaganda reveals that the effective use of information to persuade the public is not the same as the responsible dissemination of ideas. Many forms of media (i.e., advertising, political campaign speeches, public service announcements) are produced with the purpose of persuading public opinion, and might be classified as propaganda. Yet, should all propaganda be considered unethical, even propaganda aimed at causes we support? What criteria should we use to evaluate the ethical use of information? In the twenty-first century, when most of us have increasing access to a wide range of information, it is especially important for students to be equipped with the ability not only to comprehend ideas, but to evaluate this information 14 DM Add footnote to reading 16 Add footnote to reading 17 DM 15 Facing History Elective Course Outline DRAFT – NOT FOR PUBLICATION Section 7: Conformity and Obedience page 7 from a moral and intellectual perspective. That is why we encourage educators to spend time helping students develop their media literacy skills. In this section, we have provided lesson ideas, primary source documents and discussion questions aimed at helping students interpret any forms of media – from Nazi propaganda posters to advertisements on television today. By helping students develop the habit of asking and answering questions such as, “What is the intended purpose of the text? What message is being expressed? How do I know if this information is true?” we nurture their growth as the critical thinkers who are necessary for a democracy. Obedience in Nazi Germany Under what conditions are people most likely to believe what they hear or see? Does it matter where the information is coming from? Are people more likely to believe what they hear when it comes from a person or organization in a position of authority? Can propaganda inspire obedience? To what extent does a culture that nurtures obedience also motivate citizens to passively accept the information around them? Wrestling with the relationship between propaganda and obedience can help us think about the factors that may have influenced decision-making in Nazi Germany. Some observers and scholars wondered if there was something distinctive about German identity that made them more prone to obedient behavior than individuals from other cultures. Stanley Milgram, a professor at Yale University, decided to design a series of experiments to study obedience as a characteristic of human behavior in which volunteers were ordered to give electric shocks to an unseen person (who was an actor, pretending as though he was receiving this treatment) In Milgram’s words, “The point of the experiment is to see how far a person will proceed in a concrete and measurable situation in which he is ordered to inflict increasing pain on a protesting victim. At what point will the subject refuse to obey the experimenter?”18 Milgrim hypothesized that most volunteers would refuse to give electric shocks of more than 150 volts. A group of psychologists and psychiatrists predicted that less than one-tenth of 1% of the volunteers would administer all 450 volts. To everyone’s amazement, 65% gave the full 450 volts! Based on these results, Milgram concluded: The extreme willingness of adults to go to almost any lengths on the command of an authority constitutes the chief finding of the study . . . Ordinary people, simply doing their jobs, and without any particular hostility on their part, can become agents in a terrible destructive process. Moreover, even when the destructive effects of their work become patently clear, and they are asked to carry out actions incompatible with fundamental standards of morality, relatively few people have the resources needed to resist authority.19 What does Milgram’s experiment reveal about human behavior? Debriefing the experiment with subjects, Milgram learned how some of them rationalized shocking the “learner” because they would not be held responsible for their actions. But others stopped providing shocks to 18 19 DM http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Milgram_experiment#cite_note-2#cite_note-2 Facing History Elective Course Outline DRAFT – NOT FOR PUBLICATION Section 7: Conformity and Obedience page 8 the “learner,” even after being asked to do so repeatedly by the experimenter? What does this fact reveal about the nature of obedience? Why might some people choose to obey while others choose to resist? How can Milgram’s study be helpful in trying to make sense of decision-making in Nazi Germany? Historical evidence suggests that some Germans were excessively obedient to Hitler’s demands, going above and beyond to show their loyalty to the Reich. For example, Germans took it upon themselves to report their neighbors to the Gestapo, even when they were under no pressure to do so. A few, however, like Ricarda Huch, a poet and writer, refused to take the oath of loyalty to Hitler. She had to resign from her prestigious academic position and lived in Germany throughout the Nazi era in “internal exile,” unable to publish her work but also physically unharmed.20 Historian Robert Gellately refutes the argument that many Germans went along with the Nazis simply because of a desire to obey authority. His research about “Gestapo’s unsolicited agents” revealed that in most cases, informers were motivated by factors such as greed, jealousy, revenge, or a desire to be taken seriously.21 Multiple factors, including obedience to authority, antisemitism, opportunism, propaganda, fear, conformity, prejudice, and self-preservation, all working together in complex ways, likely shaped the choices of many Germans in the 1930’s and 1940’s. Studying decision-making in Nazi Germany provides an opportunity for students to practice constructing sophisticated historical arguments, as opposed to making simplistic (mono-causal) explanations for events. Obedience and resistance One of the primary questions embodied in this section involves when obedience to authority is appropriate and when such obedience goes beyond the bounds of ethical judgment. How can we distinguish obedience from unconditional or “blind obedience”—when individuals follow orders without really “seeing” or questioning what they are being asked to do with no consideration of the moral consequences of their decisions? The history of Germany in the 1930s, as well as other histories (e.g. Cultural Revolution in China) makes clear that human rights are more likely to be abused when individuals blindly obey authority—when they fail to consider whether what they are being asked to do is appropriate and morally just. Yet, other moments in history—from Gandhi’s salt march in India, to the anti-apartheid struggle in South Africa, to the civil rights movement in the United States— demonstrate that when citizens have the capacity to wisely and respectfully question authority, they can make better decisions about whether or not their obedience is ethically justified and can push for unjust laws to be changed. One argument Milgram makes is “few people have the resources needed to resist authority.” What are those resources? Where do people learn how to question authority? Do schools have a role in this effort? How can we help our students make thoughtful choices about obedience? Such questions go to the heart of the meaning of participation in a democracy. 20 21 DM DM Facing History Elective Course Outline DRAFT – NOT FOR PUBLICATION Section 7: Conformity and Obedience Facing History Elective Course Outline DRAFT – NOT FOR PUBLICATION page 9 Section 7: Conformity and Obedience page 10 Resources (What materials will help them learn about this topic?) Resources referred to in the lesson ideas: Readings and images: From Facing History and Ourselves: Holocaust and Human Behavior, “A Matter of Obedience,” pp. 210-13 Videos and audio-recordings: The Nazis: A Warning from History - Chaos and Consent Heil Hitler: Confessions of a Hitler Youth Obedience Childhood Memories Websites: German Propaganda Archive at Calvin College Handouts: Handout 7.1 Examples of Nazi Propaganda Handout 7.2 Definitions of Propaganda Handout 7.3 Heil Hitler: Confessions of a Hitler Youth – Viewing Guide Handout 7.4 Life for German Youth (1933-1939) – Analysis Worksheet Other suggested resources: Readings and images: Chapter 5, Facing History and Ourselves: Holocaust and Human Behavior “Changes at School,” pp. 175–76 “School for Barbarians,” pp. 228–31 “Belonging,” pp. 232–35 “Models of Obedience,” pp. 235–37 “Birthday Party,” pp. 237–40 “A Matter of Loyalty,” pp. 240–41 “Propaganda and Education,” pp. 242–43 “Racial Instruction,” pp. 243–45 “School for Girls,” pp. 245–46 “A Lesson in Current Events,” pp. 246–48 “Rebels Without a Cause,” pp. 249–50 “A Matter of Obedience,” pp. 210–13 “Taking Over the Universities,” pp. 172–74 “No Time to Think,” pp. 189–90 “A Refusal to Compromise,” pp. 192–93 “Do You Take the Oath?” pp. 198–200 “The People Respond,” pp. 203–4 Facing History Elective Course Outline DRAFT – NOT FOR PUBLICATION Section 7: Conformity and Obedience “Rebels Without a Cause,” pp. 249–50 “Taking a Stand,” pp. 268–69 “Defining a Jew,” pp. 201–2 “The People Respond,” p. 203 “The Hangman,” pp. 204–6 “No Time to Think,” pp. 189–91 “Threats to Democracy,” pp. 160–61 “Propaganda,” pp. 218–21 “Propaganda and Sports,” pp. 221–23 “Art and Propaganda,” pp. 223–25 “Using Film as Propaganda,” pp. 225–27 Videos and audio-recordings: Student Jamarr R. Talks about Education in Nazi Germany (51 sec) The Wave Lesson plans: Decision-Making in Times of Injustice - Lesson 9 Decision-Making in Times of Injustice - Lesson 11 Decision-Making in Times of Injustice - Lesson 12 Facing Today Fake TV Game Show About Obedience Shocks France (March 19, 2010) Decades Later Still Asking: Would I Pull That Switch (July 1, 2008) Websites The Lucifer Effect - Dehumanization Institute for Propaganda Analysis Sourcewatch Facing History Elective Course Outline DRAFT – NOT FOR PUBLICATION page 11 Section 7: Conformity and Obedience page 12 Part 2: Lesson ideas The lesson ideas presented here provide options for different ways you might use the core resources, and additional materials, to support students’ exploration of the section’s’ essential questions. We encourage you to use these ideas as a guide to support your own curriculum development. . Lesson idea #16 – Propaganda and conformity (Suggested duration: 2 class periods) Recommended journal and discussion prompts If you were the head of a group (an organization, a school, a country…) and you wanted to convince people to believe a certain idea, what might you do? Do you strongly agree, agree, disagree, or strongly disagree with the following statement: Under most circumstances, most people can be convinced to believe almost anything? Explain your answer. Under what circumstances do you think people are less likely to believe what they see or hear? Under what circumstances do you think people are most likely to believe what they see or hear? In the first few months of being appointed Chancellor, Hitler created a Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda. Why do you think Hitler might have done this? What might the director of a Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda do? What criteria do you use to determine what information is accurate and can be trusted? How do you know when what you are hearing is misleading or inaccurate? What is censorship? What is the purpose of censorship? Under what circumstances, if any, is it appropriate to ban or censor the media? What does it mean to dehumanize someone? What are the ways in which we can make individuals or groups seem unworthy or less-than-human? Activity ideas 1. Warm up - Beginning with this lesson, students engage with material that will help them answer the question, “Why did most Germans follow the policies dictated by Hitler and the Nazi Party?” Students begin to answer this question by examining the role of propaganda in German society. The following suggestions represent different ways to help students review prior knowledge and preview the material they will be studying about conformity, propaganda and obedience. Reviewing the laws passed by the Nazis: The names Nazis gave to the laws they enacted reveals the power of language to persuade. These names expressed what the Nazis wanted the German population to believe about these laws. For example, the “Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service” sends a message of improvement; it does not suggest that the law mandates firing people, even if they are doing good work, just because they belong to a particular group. What might have been the public reaction to this law if Facing History Elective Course Outline DRAFT – NOT FOR PUBLICATION Section 7: Conformity and Obedience page 13 the Nazis called it the “Law for the Discrimination against Civil Service Workers Who Happen To Be Jews, Communists or Other Individuals We Just Don’t Like” or the “Law for Firing Competent Doctors, Teachers, Judges, and City Employees Who Do Not Belong to the Nazi Party?” What message do these new names send? Students can repeat this exercise with a partner. Post the names of the following laws on the board: (Note: These are from the laws students interpreted during lesson 15) Law for the Protection of German Blood and Honor Reich Citizenship Laws Law for the Protection of Hereditary Health Law Against the Establishment of Parties Law Concerning the Hitler Youth Ask pairs to select one of these laws and then answer the following questions: ? What messages does the name of this law send? ? If you were going to name the same law, what might you call it? ? What different message might that new name send? How might this message influence the beliefs and actions of Germans? Allow time for volunteers to share their responses. Then, ask students why they think about the power of language. Why would the Nazis have cared about what the laws were called? What was their purpose in naming them? To what extent, if at all, were the names of these laws misleading? Often students understand that Nazis selected names that they thought would gather the most support for their policies. So, they wanted to highlight the ideas they thought would appeal to the German people while hiding the parts that they thought might raise concerns. So, often the names of laws distorted the actual intent of the policy. In this way, how the Nazis named laws becomes an example of propaganda – the use of information, often in misleading ways, for the purpose of persuasion. Create a working definition for propaganda- Before they begin analyzing Nazi propaganda, help students come up with a working definition for propaganda. A working definition of propaganda might include pro meaning for something and ganda meaning to reproduce. Here are some other ways to help students think more deeply about this concept: o Handout 7.2 includes several definitions of propaganda you might share with students to help them think about the different meanings of this word. You could ask students which definition/s best describe the practice of naming laws in Nazi Germany. o The reading “Propaganda,” on pp. 218-19 of the resource book, describes how Nazi Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels and Hitler believed they could use a range of media to control the beliefs and actions of German citizens. Students could read “Propaganda” for homework in preparation for this lesson. Or, you could read it aloud and ask students to develop a working definition of propaganda. Facing History Elective Course Outline DRAFT – NOT FOR PUBLICATION Section 7: Conformity and Obedience page 14 o Another way to help students think about propaganda is to ask what they might do if they wanted to convince someone—friends, parents, teachers, etc.—of an idea. What strategies might they use? What kinds of words would they employ? o At this point, you might want to remind students that within the first few months of being appointed Chancellor, Hitler created a Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda. The United States federal government, like many nations, has ministries (or departments) of defense, treasury, and education, but does not have a department of propaganda. In Nazi Germany, what might the director of a Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda do? What purpose might it serve? They could write about this question in their journals and then share responses with a partner. Pairs can then draft a working definition of propaganda to share with the rest of the class. Watch excerpt from The Nazis: A Warning from History, episode 2, Chaos and Conspiracy (24:00 – 38:27) - This excerpt from the BBC-produced documentary The Nazis: Chaos and Conspiracy describes life in the Third Reich starting when Hitler came to power (1933) until violence against Jews escalated with Kristallnacht (1939). This clip provides a review of some material students have already covered, such as the Nuremberg Laws, while previewing concepts students will be exploring in this section (e.g., conformity, propaganda, and antisemitism). While viewing this clip, ask students to identify at least one example of propaganda, conformity and obedience. Then have students use the evidence from the film to answer the question, “What are some ways the Nazi dictatorship encouraged people to both conform and obey?” So that students know what to look for as they watch, you may wish to review students’ working definitions of conformity and obedience before viewing the film. Students will continue to develop their answer to this question as they learn more about life during the Third Reich. In the clip, Erna Kranz recollected her feelings as a young woman living in Nazi Germany who witnessed violence and injustice against Jewish people yet did nothing to stop these crimes. Here is a transcript from the video: Erna Kranz: It was quite a shock….You actually thought about things more…. At first you allowed yourself to swim with the tide. You were carried along on a wave of hope, because we had it better, we had order in the country, we felt secure. But, then you really started to think. Me, personally, that is….It was a terrible shock. I have to admit it. Interviewer: But you didn’t become an opponent of the regime. Erna Kranz: No, no, no, that, no. One could have, then. But when the masses were shouting “Heil,” what could one do? You went with it. We were the ones who went along. Facing History Elective Course Outline DRAFT – NOT FOR PUBLICATION Section 7: Conformity and Obedience page 15 After reading these words or watching this clip again, ask students to reflect in their journals on the following questions: Why do you think Erna decided not to act against injustice, but to be part of the group “who went along”? What options did she feel she had? Erna asks, “What could one do?” How might you answer her given what you know about the time period? 2. Analyzing Nazi Propaganda– Facing History teachers have found that one of the most effective ways to help students understand life in the Third Reich is through studying the propaganda disseminated by the Nazis. In handout 7.1 we have included several examples of Nazi propaganda distributed during the 1930s - two posters and a page from a children’s book that exemplify Nazi propaganda that was targeted at young people. You can find many more examples of Nazi propaganda online. For example, on the German Propaganda Archive at Calvin College you can find speeches, posters, and political cartoons. Facing History’s library has a set of propaganda slides available for borrowing. Describe, interpret, evaluate: For a structured way to help students analyze Nazi propaganda, refer to the teaching strategy Media Literacy: Analyzing Visual Images. This strategy guides students through the process of describing, interpreting and evaluating what they see. We suggest that you analyze the first image together as a whole class so that you can model how to answer questions with specific evidence from the image. You might continue to analyze images as a whole class, or you might have students analyze other images in small groups or independently. Propaganda and dehumanization: After students have analyzed several examples of Nazi propaganda, be sure they have the opportunity to discuss how these images may have impacted the millions of Germans who saw it. As students will likely discover, Nazi propaganda served many purposes: to glorify the pure German race, to encourage obedience to Hitler, and to promote specific gender stereotypes. One of the main purposes of Nazi propaganda was to dehumanize Jews – to make them appear unworthy of the dignity and respect afforded to human beings. This is an appropriate time to introduce students to the term dehumanization, if you have not already done so. What does it mean to strip the humanity from someone? How might this be accomplished? What might be the consequences of dehumanizing an individual or group? Once people believe that someone is sub-human, how might that individual be treated? Students might bring up examples of dehumanization from other periods of history, such as slavery or the treatment of Native Americans. 3. Discussing the impact of propaganda: Because the topic of propaganda is so relevant to our media-filled lives, students will likely bring up many questions for discussion. You might debrief this lesson by asking students what is on their mind and then following up on their questions. Here are some other questions that can provide a starting point for a class discussion or a personal essay assignment: ? Does propaganda have to be misleading? Does it have to be untrue? Is it always harmful? Facing History Elective Course Outline DRAFT – NOT FOR PUBLICATION Section 7: Conformity and Obedience page 16 ? In Nazi Germany, propaganda could have deadly consequences. What are the consequences of media and propaganda on lives today? ? Can you think of positive uses for propaganda? Where is the line between the appropriate use of media to persuade and the misuse of media to inflict harm? ? What criteria can we use to determine whether what we see and hear can be trusted? ? Hitler is known for saying, “What good fortune for governments that people do not think,”22 and his policies were based on the premise that most individuals are conformists who do not think for themselves. What do you think of his statement of human behavior? ? The Nazis used several tactics to control information; including limiting access to media that they thought was offensive. They organized public book burnings, censored the media, and banned particular authors and artists. What have been your experiences with censorship? What are the reasons why a person, group, or government may want to restrict access to certain information? Under what circumstances, if any, do you think censorship is appropriate? Why? ? After seeing a Nazi propaganda film called The Eternal Jew, a graduate student named Marion Pritchard said: It was so cruel . . . that we could not believe anybody would have taken it seriously, or find it convincing. But the next day one of the gentiles [non-Jews] said that she was ashamed to admit that the movie had affected her. That although it strengthened her resolve to oppose the German regime, the film had succeeded in making her see Jews as “them.” And that of course was true for all of us. The Germans had driven a wedge in what was one of the most integrated communities in Europe.23 You might end this lesson by sharing this quotation with students and asking them to reflect on how they think propaganda might have influenced their lives. Questions you might use to prompt students’ journal writing include: Have you ever felt like Marion Pritchard? After seeing a movie or an advertisement or listening to a song, have you ever felt like a message about individuals or groups might stick with you, even though you knew the message is not true? 4. Analyzing Contemporary Media - Students are surrounded by advertisements and other media that are intended to influence public opinion. The messages people, especially young people, pick up from the media can have a profound impact on how individuals define themselves and how they are defined by others. The media, intentionally or unintentionally, disseminate ideas about race, gender, age, class and it can be empowering for students to be able to interpret and evaluate these texts and images. Here are some ways you can help students develop their media literacy skills while also giving them an opportunity to think about how the media influences how they see themselves and how they see others. Ask students to identify a group to which they belong (gender, race, age, religion, neighborhood, school, nation, etc.). They can begin by making an identity chart for this group that addresses the questions, “How do you perceive this group? How do you think this group is perceived by others?” Then have students look for examples of how this 22 23 DM DM Facing History Elective Course Outline DRAFT – NOT FOR PUBLICATION Section 7: Conformity and Obedience page 17 group is represented by the media (by a song, a newspaper article, advertisements, etc.). Finally, students can report on how these representations are aligned with the ideas on their identity chart. To what degree (a lot, somewhat, not much) does the media’s portrayal of this group match the student’s own characterization? To what degree (a lot, somewhat, not much), does the media’s portrayal of this group match how we think others define this group? This exercise can lead into a discussion about the relationship between the media and identity. How does the media shape who we are and how we see others? In what ways can this be helpful? In what ways can the media be harmful? Students can bring in examples of propaganda; either found on the Internet, in magazines, or on television, and then discuss why they think this text should be classified as propaganda based on the definitions they developed in class. To complicate students’ work with propaganda, include an example of media with a “positive” message, such as a public service announcement. Students could organize the examples of contemporary propaganda they have collected on a continuum from most ethical to least ethical. EXTENSION: After students analyze propaganda from Nazi Germany and from today, you might give them the opportunity to create their own propaganda posters. Begin by having students select a cause or message that is important to them. Then they can identify an appropriate audience for this message and they can brainstorm tactics that might be persuasive to this audience. If you want to spend more time teaching your students about propaganda techniques, two helpful resources include the Institute for Propaganda Analysis and the Sourcewatch web site. Both of these sites include a list of propaganda techniques as well as other examples of propaganda from different historical time periods. Assessment ideas (for class work and/or homework) The German Propaganda Archive at Calvin College has a large archive of Nazi propaganda posters. Students can pick a different poster and analyze it on their own. They can share the poster and their analysis with students in class the next day. To evaluate students’ understanding of propaganda, you could ask them to select an example of propaganda today and analyze this artifact following a similar protocol used during this lesson. Facing History Elective Course Outline DRAFT – NOT FOR PUBLICATION Section 7: Conformity and Obedience page 18 (Handout 7.1) Examples of Nazi Propaganda The caption on this poster reads: "Healthy Parents have Healthy Children." Facing History Elective Course Outline DRAFT – NOT FOR PUBLICATION Section 7: Conformity and Obedience page 19 (Handout 7.1) Examples of Nazi Propaganda Page from the German children's book, "Der Giftpilz" (The Poisonous Mushroom) published in 1938 by Julius Streicher, member of the Nazi party and founder of the Der Sturmer newspaper. The text reads, "Just as it is often very difficult to tell the poisonous from the edible mushrooms, it is often very difficult to recognize Jews as thieves and criminals..." Facing History Elective Course Outline DRAFT – NOT FOR PUBLICATION Section 7: Conformity and Obedience (Handout 7.1) Examples of Nazi Propaganda Hitler Youth poster, “Youth Serves the Fuhrer: All Ten Year Olds into the Hitler Youth” Facing History Elective Course Outline DRAFT – NOT FOR PUBLICATION page 20 Section 7: Conformity and Obedience page 21 (Handout 7.1) Examples of Nazi Propaganda This picture comes from the book Trust No Fox on His Green Meadow and No Jew on His Oath, published by Julius Streicher in 1936. The book was used in many schools. Martin Luther, the founder of the Protestant Church, is credited with saying these words in the sixteenth century. The Nazis were known for incorporating antisemitic ideas from the past into their propaganda. 24 24 http://www.calvin.edu/academic/cas/gpa/fuchs.htm Facing History Elective Course Outline DRAFT – NOT FOR PUBLICATION Section 7: Conformity and Obedience page 22 (Handout 7.2) Definitions of Propaganda Definition #1 - The spreading of ideas for the purpose of helping or harming an institution, a cause, or a person (Source: Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary) Definition #2 - Information, especially of a biased or misleading nature, used to promote a political cause or point of view. (Source: Concise Oxford English Dictionary) Definition #3 - A manipulation designed to lead you to a simplistic conclusion rather than a carefully considered one. (Source: Dr. Anthony Pratkanis, Professor of Psychology, University of California Santa Cruz) Definition #4 - The deliberate, systematic attempt to shape perceptions, manipulate cognitions [thoughts], and direct behavior to achieve a response that furthers the desired intent of the propagandist. (Source: Propaganda and Persuasion, Garth Jowett and Victoria O’Donnell, 1999) What do you think propaganda is? Write your own working definition of propaganda. Facing History Elective Course Outline DRAFT – NOT FOR PUBLICATION Section 7: Conformity and Obedience page 23 Lesson idea #17 – “He alone who owns the youth, gains the future” (Suggested duration: 1 class periods) Recommended journal and discussion prompts What messages does society send to young people today about the proper way to think and act? Where do these messages come from? To what extent do you agree or disagree with these messages? What is the purpose of education? How is education different, if at all, from propaganda? If you were designing a school that was supposed to prepare young people for their role as citizens in a democracy, what would it be like? What would students learn? What would happen at this school? How might this school be different than one that was preparing students for their role as citizens in a dictatorship? Hitler said, “He alone who owns the truth, gains the future.” What do you think he meant by this? Do you strongly agree, agree, disagree or strongly disagree with this statement? Explain. Activity ideas 1. Warm up – The purpose of this lesson is to help students explore the different strategies the Nazis used to prepare young Germans for their role as obedient followers of Hitler. You might begin this lesson by having students think about the purpose of education, especially civic education. Any of the suggested journal questions could be used to prompt students’ writing and discussion. 2. Watch Heil Hitler: Confessions of a Hitler Youth – In the 30-minute video Heil Hitler: Confessions of a Hitler Youth, Alfons Heck recalls how he became a high-ranking member of the Hitler Youth. He discusses the influence of peer pressure and propaganda on Hitler’s ability to recruit eight million German children to participate in the “war effort,” with some as young as 12 participating in murder. The interview is supplemented by archival footage. The chapters “Hitler Youth” and “Nuremberg” are most relevant for the purposes of this lesson. As students dig deeper into this history, they can watch the other chapters. Handout 7.3 includes a viewing guide for these chapters of this film. The questions on this guide follow the Levels of Questions strategy, ranging from factual to inferential to universal. 3. Explore other narratives describing life for German youth in the 1930s - Understanding history requires us to listen to many voices and Facing History teachers have found that students are especially engaged in the study of history when they have the opportunity to learn about the experiences of young people in the past. For this reason, in our resource book and video library, we have included narratives that focus on the experiences of German youth representing different perspectives (i.e. “Aryan,” Jewish, etc.) As students explore these materials, ask them to analyze these texts using a process similar to the one Facing History Elective Course Outline DRAFT – NOT FOR PUBLICATION Section 7: Conformity and Obedience page 24 they used when interpreting Nazi propaganda in the previous lesson. What message is being sent to German youth? By whom? What is the purpose of sending this message? What influence might it have on the thoughts and actions of German youth? (See handout 7.4 for a sample worksheet you might use to help students analyze these materials.) Childhood Memories - Facing History, working with Yale University, has produced Childhood Memories, a video montage of Holocaust survivors. Some of these survivors share stories of what it was like to grow up in Nazi Germany and attend German schools. We especially recommend having students view the testimonies of Frank S. and Walter K. Stories about school in Germany – The resource book includes many narratives about life for young people under the Nazis, especially focusing on education, including: “Changes at School,” pp. 175–76 “School for Barbarians,” pp. 228–31 “Belonging,” pp. 232–35 “Models of Obedience,” pp. 235–37 “Birthday Party,” pp. 237–40 “A Matter of Loyalty,” pp. 240–41 “Propaganda and Education,” pp. 242–43 “Racial Instruction,” pp. 243–45 “School for Girls,” pp. 245–46 “A Lesson in Current Events,” pp. 246–48 The jigsaw teaching strategy could be an effective way to structure students’ reading of these texts. Or, you might ask students to select two or three of these readings and then share what they have learned with a partner who may have selected different readings. As students read, encourage them to connect what they are reading to other material they have covered, such as the story of Alfons Heck or the propaganda posters. Teachers have found the text to text, text to self, text to world teaching strategy can help students make connections between what they are reading and prior knowledge, their own lives and society today. 4. Discuss the role of civic education - Having learned about education in Nazi Germany, students can discuss their ideas about the role of education in civic preparation today. Some students may express confusion about the difference between propaganda and education. Both enterprises attempt to convey information to students. You can begin this discussion by asking students to share any connections they may have made between what they read or watched and their own lives today. Or you might begin with one of the following prompts: ? What is the difference between education and propaganda? What is the difference between education and indoctrination? ? Where did young people in Nazi Germany learn about morality and ethics – about right and wrong? Where do young people learn about ethics today? What roles should school have in teaching students ethics? What have you learned in schools about right and wrong ways to think and act? Facing History Elective Course Outline DRAFT – NOT FOR PUBLICATION Section 7: Conformity and Obedience ? page 25 If you were designing a school that was supposed to prepare young people for their role as citizens in a democracy, what would it be like? What would students learn? What would happen at this school? How might this school be different than one that was preparing students for their role as citizens in a dictatorship? EXTENSION: Civic education debate- The materials in this lesson might spark students’ interest in civic education. Students could research what their school, district, or state mandate in terms of civic education. They could also analyze civics or history textbooks. Another way to deepen students’ understanding of civic preparation in a democracy is to organize a debate on the topic. Teachers have found the SPAR teaching strategy a useful structure for classroom debates. Assessment ideas (for class work and/or homework) Students’ responses to the questions on the viewing guide and/or their responses on handout 7.4 (“Life for German Youth – Analysis Worksheet) will reveal the degree to which they understand the role of propaganda in the lives of German youth. This is an appropriate time to have students add to their definitions of conformity, obedience and propaganda. They can turn in an exit card with their revised understanding of these terms. Or, you can ask them to identify a specific way that these concepts played out in the lives of German youth. Facing History Elective Course Outline DRAFT – NOT FOR PUBLICATION Section 7: Conformity and Obedience page 26 (Handout 7.3) Heil Hitler: Confessions of a Hitler Youth – Viewing Guide Questions for “Hitler Youth” Approximately how many children pledged themselves to Hitler and the Third Reich? How old was Alfons when he joined the Hitler Youth Corp? Identify at least 3 examples of propaganda that Alfons said had an impact on him. How did the propaganda impact him? How did the Nazis try to captivate the young? (Try to come up with at least three strategies they used.) What do you think was the intended purpose of showing a film like The Eternal Jew? What is racial science? Why do you think people believed it? How do you think learning about racial science influenced young school age children? Why do you think the Nazis targeted the youth? Why did they devote so much time to their education and training? What does this film reveal about how the Nazis taught young Germans about distinctions between we and they? What do you think might be the impact of these lessons? According to this film, how were the Nazis trying to shape the morals of the young? What were they teaching was the “right” way to behave? The “wrong” way to behave? To what extent do you think it is possible for governments to shape the morals of its citizens? What shapes your morals and beliefs? Questions for “Nuremberg” Where did the Nazis hold the Annual Nazi Party Conference? What was the purpose of this conference? What “mesmerizing” message did Hitler give the Youth Corp? What is the significance of Hitler referring to young people in the audience as “his youth?” What are some feelings Aflons experiences at the Nazi rally in Nuremberg? Why do you think belonging to the Hitler Youth is important to Alfons? Do you think belonging to a group is important to young people today? Why or why not? Identify an example of obedience in this film. Who is obedient? To whom? Why? Identify an example of conformity in this film. Who is conforming? To what norm or set of behaviors? Why? What are the benefits of having a charismatic government leader? What are the dangers of having a charismatic government leader? Facing History Elective Course Outline DRAFT – NOT FOR PUBLICATION Section 7: Conformity and Obedience page 27 (Handout 7.4) Life for German Youth (1933-1939) – Analysis Worksheet What message is being sent to German youth? By whom? What might be the purpose of disseminating this message? What influence might it have on the intended audience? How might it have influenced their thoughts and actions? Who else might have been impacted by this message? How so? What questions or thoughts does this document or video raise for you? Facing History Elective Course Outline DRAFT – NOT FOR PUBLICATION Section 7: Conformity and Obedience page 28 Lesson idea #18 – Obedience (Suggested duration: 1 class periods) Recommended journal and discussion prompts Think of a time when you obeyed a rule or an authority figure (a parent, teacher, group leader, etc). Why did you obey? What were the consequences of your decision? Now think about a time when you ignored or disobeyed a rule or an authority figure? Why did you resist authority? What were the consequences of your decision? What is obedience? What factors encourage obedience to authority? What is resistance? What factors encourage resistance to authority? Under what circumstances do you think it is appropriate, or even necessary, to obey authority? Why? Under what circumstances do you think it is appropriate, or even necessary, to resist authority? Why? Activity ideas Warm up – To frame the concept of obedience, we suggest beginning this lesson by giving students the opportunity to think about the role of obedience in their own lives and/or to review the role of obedience in Nazi Germany. Think-pair-share: Ask students to identify specific moments of obedience from their own lives, perhaps even as recent as the same week or day. You could use a prompt such as: Think of a time when you obeyed a rule or an authority figure (a parent, teacher, group leader, etc). Why did you obey? What were the consequences of your decision? Now think about a time when you ignored or disobeyed a rule or an authority figure? Why did you resist authority? What were the consequences of your decision? In the sharing portion of this exercise, focus on the reasons why students choose to obey and to resist authority. You could also ask students to react to the adjective “obedient.” Do they think of this as a positive quality or a negative quality? Some students may already have a nuanced answer to this question, understanding that obedience is a positive trait under certain circumstances and dangerous under other circumstances. Other students may have a more simplistic response to this question. At this point, the purpose of asking these questions is to pique students’ thinking and help them articulate their initial thoughts. At the end of this lesson, students can return to their writing and consider how (or if) any of their ideas may have shifted. Developing vocabulary: Give students the opportunity to construct a working definition for obedience and conformity (or review earlier definitions). Review: Have students brainstorm as many examples of obedience from their study of Nazi Germany. Examples could come from films or readings. One way to structure this exercise is as a graffiti board – where students record their ideas silently on a whiteboard or chalkboard. Facing History Elective Course Outline DRAFT – NOT FOR PUBLICATION Section 7: Conformity and Obedience page 29 2. Watch Obedience: The film Obedience is a documentary about Stanley Milgram’s famous experiment. It can be borrowed from Facing History’s library. We strongly recommend that you watch the entire film before deciding whether or not it is appropriate for your students. The film Obedience is approximately 45 minutes long. To allow ample time for setting up the context of the film and debriefing it, many teachers choose to show students excerpts. You might want to focus students attention on “teacher” (subject) who refuses to go along with the experimenter’s instructions (9:30-11:45) and another clip where the “teacher” volunteer obeys the instructions of the test administrator to the most advanced degree (minutes 21:50–35:15). In the final five minutes of the film (39:40-44:17), Milgram describes variations to the experiment and how that influenced the results. In particular, this excerpt shows how subjects were influenced by the actions of people around them. When the group obeyed, the subject was more likely to obey, and vice versa. Thus, this clip can be useful in helping students consider the relationship between conformity and obedience. In addition to or instead of viewing Obedience, students can read “A Matter of Obedience” (pp. 210-212 in HHB). This reading provides a description of this experiment. Pre-viewing suggestions: Explain to students that in this lesson they will learn about a famous study conducted by Professor Stanley Milgram. He wanted to understand why so many people went along with Hitler’s orders. In a brief lecture, give students some background information about Milgram’s experiment or have students read the following excerpt from “A Matter of Obedience” in the resource book: Working with pairs, Milgram designated one volunteer as “teacher” and the other as “learner.” As the “teacher” watched, the “learner” was strapped into a chair with an electrode attached to each wrist. The “learner” was then told to memorize word pairs for a test and warned that wrong answers would result in electric shocks. The “learner” was, in fact, a member of Milgram’s team. The real focus of the experiment was the “teacher.” Each was taken to a separate room and seated before a “shock generator” with switches ranging from 15 volts labeled “slight shock” to 450 volts labeled “danger–severe shock.” Each “teacher” was told to administer a “shock” for each wrong answer. The shock was to increase by 15 volts every time the “learner” responded incorrectly. The “teacher” received a practice shock before the test began to get an idea of the pain involved. Some teachers ask students to form a hypothesis about the results of Milgram’s study. Prompts that might guide students’ ideas include: • What percentage of volunteer “teachers” do you think will refuse to give the “learner” any electric shocks at all? • What percentage of volunteer “teachers” do you think will refuse to give electric shocks of more than 150 volts? • What percentage of volunteer “teachers” do you think will give shocks up to 450 volts (labeled “danger–severe shock”)? You can record students’ hypotheses on the board so you can review them after they learn the results of Milgram’s experiment. Before you show the video, you might share Facing History Elective Course Outline DRAFT – NOT FOR PUBLICATION Section 7: Conformity and Obedience page 30 Milgram’s hypothesis with the class: he predicted that most volunteers would refuse to give electric shocks of more than 150 volts. During-viewing suggestions: While viewing this clip, ask students to closely observe the behavior of the “teacher” and the test administrator. We suggest that students are provided ample time to write in their journals about what they have viewed. If you use several excerpts, you might give students the opportunity to write after each one. Students can be encouraged to write about what they see and their reactions to this information. Two-column note-taking can be a useful structure to help students capture information about what they see and their reactions to this information. The following questions might be written on the board or on a note-taking template to guide students’ viewing of the clip: What do you observe? What language is used by the experimenter and the “teacher”? What is the teacher’s body language? How does the teacher act as he administered the shocks? What does he say? What pressures were placed on him as the experiment continued? How does viewing this film make you feel? What ideas and questions does it raise for you? This film has been known to provoke strong emotional reactions in students. Many teachers have been surprised when students laugh at sensitive moments of the documentary. This laughter can be interpreted in many ways, but often it is a sign of discomfort or confusion, not of enjoyment. Those who study human behavior say that laughter can be a way of relieving tension, showing embarrassment, or expressing relief that someone else is “on the spot.” You might share these findings with students so that they see laughter as something other than a sign that something is funny or foolish. Post- viewing suggestions: Teachers who have used this film comment on the importance of planning sufficient time for debriefing during that class period, so that students can process their reactions before moving on to their next class. Let them discuss first….After students view the clip, inform them that 65 percent of the volunteers gave the “learner” the full 450 volts. (You may want to remind students that the “learner” in the experiment was a member of the research team and was not actually receiving any electric shocks.) The Think-pair-share or fishbowl teaching strategies can help students process their responses to what they just viewed. There are so many ways that this film can be a springboard to deep discussions about obedience and conformity in the past and today. You might begin by asking students to generate a list of questions that they want to talk about. Here are other questions that teachers have used following this film. These questions can be used as the basis for writing or discussion activities: ? What were the results of this experiment? ? Why do people go all the way to 450 volts? Why do some refuse? ? What does this study teach us about human behavior? ? What does this study teach us about Nazi Germany? ? What conclusions does Milgam draw from this experiment? To what extent do you agree with his conclusions? Facing History Elective Course Outline DRAFT – NOT FOR PUBLICATION Section 7: Conformity and Obedience ? ? ? ? ? ? page 31 How do the results of this experiment relate to what you know about other moments in history? How do the results of this experiment relate to what you have observed or experienced about people today? How do people learn about obedience? Do you think this is something that is taught to people or is it just an instinctive part of human nature? Explain. How should young people, especially, be taught to approach issues of obedience? What should they learn about obeying authority? How might they be taught these lessons? Milgram concluded that “relatively few people have the resources to resist authority?” To what extent do you agree with this statement? What resources are needed to resist authority? How might someone acquire or develop these resources? Some people make a distinction between obedience and “blind obedience.” How can you explain the difference between these concepts? Under what conditions might someone obey “blindly”? 3. Exploring the ethical dimensions of obedience and resistance: For societies to function it is critical that individuals obey authority. Thus, one possible learning goal for this lesson is for students to develop their ability to draw distinctions between situations when it is appropriate to obey authority and situations that call for resistance to authority. One way you can help students practice this important skill is to ask them to create examples of situations when it is good, and even vital, that individuals obey authority. For example, as a matter of public safety, when a mayor asks citizens to leave town before a hurricane, it is important that residents of that town listen. Then, ask students to brainstorm examples that call for resistance to authority. These examples could come from history or from students’ own experiences. You might have students work in groups to develop at least one obedience scenario and one resistance scenario. Students could read the scenarios aloud and ask the rest of the class to suggest if they think that scenario calls for obedience or resistance. If there are scenarios where the class does not agree about the appropriate course of action, give students the opportunity to explain their positions and to listen to the ideas of others. This also could be structured as a barometer activity. Another way to get at this concept is by reminding students of Erna Kranz’s statement from the film The Nazis: Chaos and Conspiracy: “When the masses were shouting ‘Heil,’ what could one do? You went with it. We were the ones who went along.” Kranz represents an example of when the human desire to conform yields disastrous consequences. Yet, is conformity or obedience always bad? How would society function if we never obeyed authority or conformed to the norms of a community? Groups of students might make lists of situations when conformity or obedience is appropriate and situations when conformity or obedience is inappropriate. After either of these exercises, students can determine the criteria they might use to evaluate when it is acceptable or unacceptable to obey authority or conform to the Facing History Elective Course Outline DRAFT – NOT FOR PUBLICATION Section 7: Conformity and Obedience page 32 norms of the group. Groups can present their criteria to the class verbally. Or they can record their criteria on a poster, put their posters on the wall, and do a gallery walk of the room. A final activity might ask students to determine their own “obedience and conformity criteria,” drawing on the ideas from the various posters. Assessment ideas (for class work and/or homework) To evaluate how students have been able to connect the Milgram study to themes in this course you can ask them to respond to themes in the course you can ask them to respond to the questions: What were the results of Milgram’s study? Were you surprised by them? Why or why not? What does this teach you about human behavior? What does it teach you about Nazi Germany? You can also use any of the other journal prompts or discussion questions included in this lesson idea as the basis of a short essay assignment. Or you might ask students to answer a question such as: This section focused on the themes of obedience, conformity and propaganda. For each of these terms, do the following: 1) Define the term in your own words, 2) Explain how this term helps you understand decision-making in Nazi Germany, 3) Identify one important idea that you hope to remember related to this concept, 4) List one question that you have related to this concept. Encourage students to use their journals to help them with this assignment. Facing History Elective Course Outline DRAFT – NOT FOR PUBLICATION