* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download FedViews

Fear of floating wikipedia , lookup

Full employment wikipedia , lookup

Monetary policy wikipedia , lookup

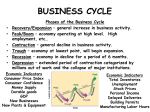

Business cycle wikipedia , lookup

Great Recession in Europe wikipedia , lookup

Post–World War II economic expansion wikipedia , lookup

Transformation in economics wikipedia , lookup

Phillips curve wikipedia , lookup

Twelfth Federal Reserve District FedViews February 11, 2010 Economic Research Department Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco 101 Market Street San Francisco, CA 94105 Also available upon release at www.frbsf.org/publications/economics/fedviews/index.html Glenn Rudebusch, senior vice president and associate director of research at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, states his views on the current economy and the outlook: The economy appears to be in a moderate recovery, but questions remain about the durability of growth and whether it can be sustained by private demand as the impetus from the federal fiscal stimulus fades later this year. While the recession may be over, production, income, sales, and employment are at very low levels. With moderate economic growth, it could take years for the economy to pull out of its deep recessionary hole. Accordingly, the unemployment rate seems likely to remain elevated for several years. The associated economic slack has reduced inflationary pressures. Over the past year, the core PCE price index has increased by 1.5 percent—about a percentage point lower than before the recession. Going forward, we expect inflation to continue to edge down, averaging about 1 percent in 2010. Given the remarkable nature of the recent financial crisis and recession, the amount of uncertainty around our baseline forecast is likely to be larger than usual. However, the risks to the outlook appear to be well balanced. Economic growth may turn out weaker if the distress in labor markets curtails income and spending more than we anticipate. So far, during this downturn, the economy has lost 8.4 million jobs. We anticipate a turnaround this year, but, instead, we could be facing a jobless recovery with long durations of unemployment degrading the skills and abilities of potential workers. Alternatively, a more optimistic scenario is suggested by a few recent positive readings. Notably, over the past few months, temporary employment and the average workweek have risen. The latter increase reflects in part longer shifts for some part-time workers. Such signs often presage an increase in permanent employment. In addition, there may even be some upside risk to growth from higher consumer spending. The level of consumption remains well below its pre-recession trend, in part because households remain quite cautious. As uncertainty about the health of the economic recovery is reduced, pent-up demand may provide a more pronounced snapback to earlier levels of spending and boost growth above our expectations. There are also upside and downside risks to the inflation outlook. Some of the historical evidence linking economic slack and inflation would suggest somewhat more disinflation than we anticipate. (See FRBSF Economic Letter 2010-02, “Inflation: Mind the Gap.”) However, measuring the precise degree of economic capacity and slack is always difficult. The views expressed are those of the author, with input from the forecasting staff of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco. They are not intended to represent the views of others within the Bank or within the Federal Reserve System. FedViews generally appears around the middle of the month. The next FedViews is scheduled to be released on or before March 22, 2010. In contrast to the experience of some countries, where productivity has fallen after large adverse financial shocks, U.S. productivity has grown quite rapidly over the past year. If a significant portion of this jump in productivity is permanent, as anecdotal reports suggest, potential output could grow faster than we have estimated. The resulting wider output gap, which would help reconcile labor-side and product-side measures of economic slack, would argue for even lower inflation going forward. Indeed, while core inflation has already fallen about 1 percentage point since the recession began, measures of labor compensation are down by about 2 percentage points. There is also a risk of higher inflation going forward. In part because of the high levels of the federal fiscal deficit, the Federal Reserve balance sheet, and bank excess reserves, some worry that the Fed’s monetary stimulus will not be appropriately removed when the economy recovers. Such fears could help fuel higher inflation expectations and, in turn, higher inflation. So far, readings on inflation expectations have been mixed. (See FRBSF Economic Letter 2009-31, “Disagreement about the Inflation Outlook.”) Expectations of inflation over the next five years have been falling, while longer-term expectations have edged up. (Recent measures of inflation expectations from financial markets are similarly ambiguous. See FRBSF Working Paper 2008-34, “Inflation Expectations and Risk Premiums in an Arbitrage-Free Model of Nominal and Real Bond Yields.”) Economic theory and evidence have not established which time horizon is more relevant for determining prices and inflation over the next year or two, but there may be some risk that higher inflation expectations could become a self-fulfilling prophecy. To combat the financial crisis and recession, the Federal Reserve took several actions. It lowered short-term interest rates to near zero, eased longer-term credit conditions, and reduced longer-term yields by purchasing U.S. Treasury and government agency securities. The Fed also provided short-term liquidity to alleviate financial market strains. One aspect of this provision of liquidity involved a reduction in the spread of the discount rate—the rate at which the Fed lends to depository institutions through its primary credit facility— from 1 percentage point over the target federal funds rate to 1/4 percentage point. As financial market strains have eased, the private sector has been able to fulfill its own funding needs again and the Fed’s provision of liquidity has shrunk drastically. In response to the recovery of private funding markets, the Fed has also reduced the maximum maturity of discount window loans. A likely next step in normalizing the terms of these loans would be to raise the discount rate spread over the fed funds rate target. Importantly, such an increase in the discount rate would be a purely technical adjustment in response to improved financial market functioning. It would not reflect a change in the stance of monetary policy, nor foreshadow a removal of monetary accommodation. Ideally, the level of the spread should be low enough to encourage the use of the discount window as a backup source of funds during temporary liquidity shortfalls or financial market disruptions. However, the spread should be high enough to discourage its use as a routine source of funds when market alternatives are available. Balancing these objectives may involve some learning over time to determine the spread’s appropriate level. A self-sustaining economic recovery? Real GDP The large output gap will persist Real GDP Percent 10 Percent change at seasonally adjusted annual rate 8 FRBSF Q4 Forecast $, Trillions 15 Seasonally adjusted chained 2005 dollars FRBSF Potential Output 6 14.5 4 14 2 Output Gap 0 -2 13.5 FRBSF Forecast -4 13 -6 12.5 -8 00 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 2006 12 Enormous pool of unemployed workers Unemployment Rate Jan. 2008 2009 2010 2011 PCE Price Inflation Percent 5 Percent change from four quarters earlier 10 9 6 0 3 -1 95 96 97 98 99 00 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 Has labor market reached bottom? A few promising signs on the margin Nonfarm Payroll Employment Workweek and Temporary Employment Millions of employees; seasonally adjusted 139 Change 138 -224K October November +64K December -150K -20K January 137 136 134 133 132 Jan. 131 3 Average workweek* (right axis) Hours 35 Jan. 34.5 2.5 34 05 06 07 08 09 10 2 33.5 1.5 1 33 Temp. help employment (left axis) 130 129 04 Millions 3.5 135 From peak -8.4M 03 1 4 78 80 82 84 86 88 90 92 94 96 98 00 02 04 06 08 10 12 02 2 Core PCE Price Index 5 01 3 Q4 7 FRBSF Forecast 4 FRBSF Forecasts Overall PCE Price Index 8 00 2012 The recession has lowered inflation Percent 11 Seasonally adjusted 2007 0.5 32.5 90 92 94 96 * Three-month moving average 98 00 02 04 06 08 10 Consumers showing signs of life Real Personal Consumption Expenditures Remarkable strength in productivity Billions of 2005$ 10000 Seasonally adjusted annual rate Dec. Nonfarm Business Labor Productivity Annualized percent change from eight quarters earlier 9500 9000 8500 8000 7500 7000 00 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 89 Wages and benefits are barely growing Labor Compensation 93 95 99 01 03 05 07 Headline PCEPI Inflation Forecasts Median forecasts from Survey of Professional Forecasters Percent 2.75 Forecast for average inflation six to ten years ahead 8 Nonfarm Compensation per Hour 97 Mixed readings on inflation expectations Percent 9 Percent change from four quarters earlier 91 Percent 5 4.5 4 Q4 3.5 3 2.5 2 1.5 1 0.5 0 09 7 2.5 6 2.25 5 Q1 4 Q4 3 Employment Cost Index 2 Forecast for average inflation over the next five years 2 1 1.75 0 89 91 93 95 97 99 01 03 05 07 09 Fed’s balance sheet: size and composition Federal Reserve Assets Aid systemicallyimportant firms Billions of Dollars 2500 2/3 Jul 2008 2009 2010 Discount rate spread could be raised Percent 7 Discount Rate and Federal Funds Rate Discount Rate 6 2000 Provide shortterm liquidity 5 Ease overall credit conditions Oct Jan Apr 2009 1500 4 Federal Funds Target 1000 3 2 2/3 500 Treasury portfolio and other assets Oct Jan Apr 2007 2008 1.5 2007 Effective Federal Funds Rate 1 0 Jul Oct Jan 2010 0 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010