* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download economic insight SOUTH EaST aSIa Quarterly briefing December 2011 global uncertainty unsettles

Transition economy wikipedia , lookup

Non-monetary economy wikipedia , lookup

Steady-state economy wikipedia , lookup

Nouriel Roubini wikipedia , lookup

Ragnar Nurkse's balanced growth theory wikipedia , lookup

Economic growth wikipedia , lookup

Chinese economic reform wikipedia , lookup

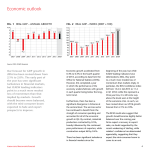

economic Insight South East Asia Quarterly briefing December 2011 Global uncertainty unsettles markets, but will it unsettle ASEAN growth? Welcome to the second issue of the ICAEW Economic Insight: South East Asia, a new quarterly forecast for the region prepared directly for the finance profession. Produced by Cebr, ICAEW’s partner and acknowledged experts in global economic forecasting, it provides a unique perspective on the prospects for South East Asia over the coming years. We mainly focus on the largest economies of the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) – namely Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam. Since the last edition, market concerns about the eurozone have been rising ever higher and the currency union appears to be heading towards further problems, with supposedly final agreements proving temporary and insufficient. This has severely undermined business and consumer confidence, leading us to revise down the growth forecast for the region, whereas that for the US looks broadly unchanged. Most commodity prices have started to come down as expected, although oil still remains higher than anticipated. The large ASEAN economies have started to be affected by rising uncertainty about Western economies, leading regional governments and central banks to revise national growth forecasts down. The US appears sufficiently resilient to avoid a recession, but its economy will take a long time to get back to sustained high economic growth. So many houses are being sold cheaply due to foreclosure that new building is weak. With mortgage delinquencies rising again, more properties will have to change ownership from the over-indebted to those with spare savings before new building relieves the labour market. BUSINESS WITH CONFIDENCE icaew.com/economicinsight The US housing bust indirectly catalysed another crisis, namely that of eurozone sovereign debt. The recession exposed weak economies previously sheltering behind the solid euro. Since then, in a distant echo of the Asian Financial Crisis, contagion has been spreading from country to country. Bond spreads measure the temperature of feverish speculation and the question is: who will succumb next? So far, the proposed remedies have proved ineffective as they only treat symptoms. Close fiscal union or exit are the obvious cures, but this pill still seems too bitter to swallow. So should ASEAN prepare for a global downturn? ASEAN growth to diverge from advanced economies The short answer is ‘no’. Although they are dramatic events that will shape the region, the troubles of Europe should not derail the train of prosperity. ASEAN’s economic growth prospects easily outpace the sluggish US and eurozone and also leave the rest of the world trailing. Of course, the headline figure of annual GDP growth of 4.8% in 2011 glosses over country-specific developments, which are addressed below. But although the world’s major economic blocks are slowing to about 1.6 % year-on-year growth this year and just 1.0% in 2012, ASEAN is forecast to plough on, maintaining its rate of output expansion next year. Figure 1: Comparison of annual economic growth rates by region, annual percentage change % 8 6 4 2 0 -2 -4 2005 2006 2007 ASEAN 2008 2009 World 2010 2011 2012 2013 US and eurozone Source: IMF, Cebr analysis This contrasts with the general world economy, which is expected to slow due to the travails of the West and an easing of China’s ferocious march. This should, in turn, have a dampening effect on commodity prices. In summary, commodities producers, industrialised economies and the Asian giants China and India are predicted to slow in 2012. But we think ASEAN should be able to keep going relatively undisturbed, due to the strength of its domestic demand and growing regional economic integration. For instance, trade with China should expand steadily even if its economy slows to about 7.5%, which is the soft landing scenario. Even this lower growth rate would, after all, still result in an enormous absolute increase for the world’s secondlargest economy. Looking further ahead, ASEAN GDP growth should pick up in 2013, driven by Indonesia. With nearly 40% of regional output, the world’s most populous Muslim country is the major factor in determining the overall growth rate of the 10 member states. As global growth icaew.com/economicinsight cebr.com starts rising again in 2013, South East Asia is expected to benefit, raising its weighted growth rate to 5.4%. By this time, the emerging markets will again have outpaced the advanced economies, making the latter a progressively smaller part of the world economy. Figure 1 illustrates that the world average growth rate is moving away from the West towards emerging markets. In other words, Asia is becoming the main factor in world growth, and ASEAN plays an important role in this global shift. Export growth continued into Q3 2011, but is likely to slow markedly Export volume figures show that ASEAN has overtaken the emerging market average compared to the trade volume during the financial crisis. The latest available data from around the middle of the year shows a small downturn in trade, whereas our focus region kept expanding its foreign sales. This completes the turnaround from the depth of the financial crisis, when a collapse of export orders hit the region especially hard – exports are up around 80% compared with the bottom reached in Q1 2009. The strong turnaround of fortunes is a testament to the economic prowess of ASEAN, but it also highlights the dependence on outside demand. Cautionary signs of a possible export decline have emerged from trade indicators such as IATA’s air freight figures, down 2.7% year on year in September, and the number of ships passing through the Suez Canal falling 3.2% year on year. These show a slowing of trade in the third quarter, in line with weaker industrial growth and retail sales in many major economies. While China has been the main focus of attention, it is only a matter of time until India also starts to suck in growing import volumes as economic growth creates a surge in middle-class consumers. A Malaysian free trade agreement that came into effect on 1 July appears a smart move, considering that by 2030, India is forecast to be the world’s biggest country with a population of 1.5bn. Regardless of bright future prospects, ASEAN’s growth drivers have already changed. Exports are increasingly serving domestic consumption rather than being the historical growth drivers that made the Asian Tiger economies models of development. As pointed out in the previous edition, that means a smaller export contribution to GDP as economies mature into significant markets in their own right. Figure 2: Export volume index; September 2008 =100 120 110 100 90 80 70 60 2008 2009 ASEAN 2010 Emerging Markets 2011 World Advanced Economies Source: CPB, IMF DOTS, Cebr analysis economic insight – south e a st a sia December 2 011 Country focus: Malaysia Malaysia is a microcosm of the ASEAN as it combines nearly the whole range of economic activities found throughout the region. The country has a wealth of natural resources, supplying palm and mineral oils for the world market. A highly developed electronics industry competes with other world leaders in the field. In services, a burgeoning tourism industry brings employment to remote areas, with international arrivals having grown an annual average of 12.9% since 2000, while the world-leading Islamic finance industry underlines aspirations to expand business services. With more than one in five ringgit worth of goods going to China according to the latest IMF data, it has become the largest export market for Malaysia; this is opening fresh opportunities while traditional customers from Europe and the US struggle with structural problems that will limit economic growth. Despite these successes, with 2010 per capita GDP of $8,200 the country remains caught between predominantly rural Asian economies (which earn below $5,000 per capita), and the newly industrialised countries (upwards of $18,000 per capita). While investment in infrastructure offers the prospect of increasing competitiveness in manufacturing, the large geographical size of the country probably limits the scope for full-scale industrialisation seen in countries such as Korea or Taiwan, which are three and ten times smaller respectively. Although well-diversified, the country’s economy is highly sensitive to global demand, demonstrated by swings of over eight percentage points in annual GDP growth during recessions. Looking ahead, a rising middle class is likely to temper this variability somewhat as rising incomes allow a more inward-focused industrial structure with a growing service sector share of output. The Asian Development Bank estimates that 64% of the population will have joined the middle class by the end of the decade. This evolution is evident in the increase in domestic consumption shown in Figure 3, supported by both rising wages and the development of consumer credit. The refocusing of the economy away from the West towards Asia and more stable domestic demand driven by a general increase in living standards should facilitate the gradual move to high income status. ASEAN inflation will come down in 2012, but only temporarily Strong economic growth will bring elevated inflation in its wake, with various factors pointing to structural price increases in future. A major factor influencing inflation in the region is the Chinese labour market, which used to offer a seemingly infinite source of cheap workers. An increase in nominal rural wages exceeding 20% this year (and still accelerating) has reduced the incentive of migrant workers to move, cutting labour supply in coastal manufacturing centres. A spike in wages, as well as the emergence of organised labour demands for better pay and conditions, means that imported deflation from cheap Chinese products will probably be a thing of the past. In fact, China is likely to turn from a deflationary factor for the world economy into an inflationary one as its thirst for commodities has sent prices soaring. Although commodity prices should dip in 2012 – non-oil commodities have already fallen about 10% from their peak – it will probably take a long time for rising production to meet surging demand, with structurally higher prices the logical outcome. The implication of structurally higher inflation is tighter monetary policy, which in turn implies a reduction in the potential growth rate for a given level of inflation. The upshot from this is that ASEAN countries will either have to live with faster price rises or lower growth – see projected inflation rates in Figure 4 that are in line with growth forecasts further down. Singapore has had higher inflation than Malaysia since its emergence from the financial crisis, driven by high economic growth in the period and a tight labour market. This anomaly of the wealthier economy growing faster and seeing quicker price rises is expected to reverse as the Singaporean economy enters a new era of slower growth. Figure 4: Consumer price index, year-on-year change % 12 10 8 6 4 2 0 Figure 3: Malaysian household consumption expenditure and GDP growth, annual change -2 -4 2007 2008 2009 Indonesia % 12 10 2010 2011 Malaysia 2012 2013 Singapore Source: IMF, Cebr analysis 8 6 4 2 0 -2 -4 -6 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 Malaysia household consumption Malaysia quarterly GDP growth Source: IMF, Department of Statistics Malaysia, Cebr analysis icaew.com/economicinsight cebr.com With the population putting greater emphasis on stable prices, we expect the Monetary Authority of Singapore to trade some output expansion for higher price stability. As a consequence, Singapore’s annual rate of consumer price inflation is expected to fall gradually to about 2.0% as commodity prices fall and then increase slightly to about 2.5% by the end of 2013. In addition to healthy growth, a reduction in food and fuel subsidies and the planned introduction of a value-added tax in Malaysia will fuel inflation there despite falling commodity prices. This should result in an annual CPI increase of 2.9% in 2012 and 3.2% in 2013. In Indonesia, strong growth due to strong investment spending and rising domestic demand should fuel price economic insight – south e a st a sia December 2 011 rises, fanned by limited infrastructure. The outcome is projected to be inflation of 5.0% in 2012 and 5.9% in 2013 – higher than in Singapore and Malaysia, but a reasonable rate for a fast-growing emerging market. Mixed performance at the country level in 2012 Middle income countries to pace ahead Many of the factors regarding Malaysia have already been discussed in previous sections. As a result of slowing demand for electronics products and falling commodity prices, as well as pressure on household budgets due to higher taxes and subsidy cuts, we anticipate a slowing of GDP growth from 4.5% in 2011 to 4.3% in 2012. An upturn of the electronics cycle as well as solid consumption spending should support the economy in 2013, pushing annual growth to 5.6% for the year. Splitting the ASEAN members into country groups (as defined by the World Bank) reveals some divergence in annual GDP growth rates. For one, the high income economies Singapore and Brunei have been more affected by the global financial crisis than the other groups. They are expected to grow by 4.8% in 2012 and 3.6% in 2013. Brunei’s dependence on petrochemicals makes it vulnerable to swings in energy prices, while Singapore’s economy is mainly externally focused in both the industrial and service sectors. The strong growth of high-income countries is projected to moderate, falling to the bottom of the comparison in the next two years. Figure 5: Growth rate forecast by World Bank country grouping % 14 12 10 8 6 4 2 0 -2 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 Low income Lower-middle income Upper-middle income High income Source: IMF, Cebr analysis At 5.4% in 2012 and 6.1% in 2013, the highest growth rate is expected from lower-middle income countries, a group which comprises Indonesia, Laos, the Philippines and Vietnam. These countries, and especially Vietnam, are expected to benefit from rising labour costs in China, which is likely to lead to a shift of light manufacturing to lower-cost countries in the region. Relatively small export sectors and rising domestic demand is another main factor, which has the added benefit of insulating economies from external shocks – as evidenced by stable growth for this group throughout the financial crisis. With their limited links to the world economy due to a small export base, low income economies Myanmar and Cambodia were also little affected by the global recession. Upper-middle income economies Thailand and Malaysia were badly hit, on the other hand, compensated by a larger post-recession bounce. Both groups are expected to grow by similar rates, namely around 4.2% in 2012 and 5.0% in 2013. icaew.com/economicinsight cebr.com In this section, we address the outlook for selected ASEAN economies, summarised in Figure 6. Indonesia followed emerging markets Turkey and Brazil in cutting interest rates even though inflation was still high. An attempt to head off the effects of the slowing global economy on the country and to discourage hot money inflows probably contributed to the decision. If economic stability can be maintained, strong investment and domestic consumption should support growth of 5.6% in 2012 despite worsening terms of trade, 0.6 percentage points lower than in 2011. These factors and rising exports should continue to support the country, resulting in growth returning to a level of 6.2% year on year in 2013. An unexpected and sudden turn towards a more democratic process in Myanmar is opening up new perspectives for the country. If maintained, an increase in tourism from a low base, as well as foreign investment, is likely to give a boost to an economy with fast-growing ties to giant neighbour China. This may make up for some delays to a massive hydropower project with significant environmental and social consequences put on hold due to popular discontent – another new development for the country. For 2011, we expect growth of just 3.0%, rising to 3.8% in 2012 and 4.6% in 2013. Figure 6: Country-level GDP growth forecasts % 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 Indonesia Malaysia Myanmar 2011 Philippines Singapore 2012 Thailand 2013 Source: Cebr analysis economic insight – south e a st a sia December 2 011 The Philippines was hit by weak exports, especially electronics products, this year after a healthy growth in the first quarter. Strong private demand held up the economy, but a bump in imports is expected to bring annual growth for 2011 to just 4.3%. Despite strong consumer spending growth, a chronic lack of investment in infrastructure holds the country back, making the success of an announced public-private partnership scheme important for future prospects. Assuming some success on this measure, we anticipate annual GDP growth of 4.5% in 2012 and 5.2% in 2013. falling from about 4% to just 2.3% due to the standstill of Bangkok, which accounts for around 40% of GDP. Although ultimately destroying wealth, natural disasters often boost growth in their wake due to reconstruction efforts. To some extent, repairs and rebuilding should support the economy and substitute for weaker export markets next year. Coupled with strong consumption due to public transfers, this is expected to lift growth in 2012 to 4.4%. A global recovery and strong output expansion in neighbouring countries should result in a further growth increase of 0.2 percentage points to 4.6% in 2013. Elevated inflation and a widespread perception of excessive immigration are leading to some discontent in Singapore, but unemployment remains near 2.0%. Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong announced that the government had reduced its growth target to 3–5%, compared to performance of 7–8% previously. For 2011 and 2012, we expect annual GDP growth of 4.9% and 3.7% respectively. Benefiting from its position as a regional business service hub and a competitive industrial sector, Singapore’s growth should rise to about 4.1% in 2013. These forecasts are based on a scenario of a weak economic environment in the Western economies, but an avoidance of outright, sustained recession. The eurozone debt crisis has the potential to seriously undermine this outlook by threatening the stability of the banking system and by pushing consumer and business confidence further down. The other main risk that may derail the global economy is a possible collapse of the Chinese construction sector. Although unlikely due to the ability of the state to stimulate the economy via credit and fiscal means, falling house prices may lead to a contraction in credit and thus a sharp slowing of the real economy. Currently, however, it appears that the eurozone may avoid an implosion and that China can engineer a soft landing. The unusually heavy monsoon rains that hit Thailand are wreaking havoc on the country’s economy. The GDP growth forecast for 2011 was revised down sharply, ICAEW ICAEW is a professional membership organisation, supporting over 136,000 chartered accountants around the world. Through our technical knowledge, skills and expertise, we provide insight and leadership to the global accountancy and finance profession. Our members provide financial knowledge and guidance based on the highest professional, technical and ethical standards. We develop and support individuals, organisations and communities to help them achieve long-term sustainable economic value. Because of us, people can do business with confidence. Cebr Centre for Economics and Business Research is an independent consultancy with a reputation for sound business advice based on thorough and insightful research. Since 1993, Cebr has been at the forefront of business and public interest research. It provides analysis, forecasts and strategic advice to major multinational companies, financial institutions, government departments and trade bodies. For enquiries or additional information, please contact: Leisl Pillay T (+65) 6407 1527 E [email protected] icaew.com/economicinsight cebr.com economic insight – south e a st a sia December 2 011 ICAEW 9 Temasek Boulevard 09–01 Suntec Tower Two Singapore 038989 icaew.com/southeastasia ICAEW Chartered Accountants’ Hall Moorgate Place London EC2R 6EA UK icaew.com © ICAEW MKTPLN10851 11/11