* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download PDF

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

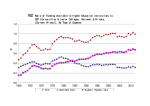

Agricultural Economics, 1 (1987) 195-207 Elsevier Science Publishers B.V., Amsterdam- Printed in The Netherlands 195 On Why Agriculture Declines with Economic Growth Kym Anderson Department of Economics, University of Adelaide, Adelaide S.A. 500 1 (Australia) (Accepted 15 April 1987) Abstract Anderson, K., 1987. On why agriculture declines with economic growth. Agric. Econ., 1: 195-207. When economic growth is characterised by a slow rise in the demand for food and rapid growth in farm relative to non-farm productivity, it is understandable that agriculture in a closed economy declines in relative terms as that economy develops. But why should agriculture decline in virtually all open growing economies as well, including those able to retain a comparative advantage in agricultural products? A key part of the answer is that the demand for non-tradable goods tends to be income elastic, so resources are diverted to their production . . even m open economLes. Introduction One of the dominant changes that characterises a growing economy is the proportionate decline in the agricultural sector. This phenomenon is commonly attributed to two facts: the slower rise in the demand for food as compared with other goods and services, and the rapid development of new farm technologies which lead to expanding food supplies per hectare and per worker (Schultz, 1945; Kuznets, 1966; Johnson, 1973). It is true that such conditions could lead to a relative decline of agriculture globally, or in a smaller closed economy. But why does agriculture decline in virtually all open growing economies? Might not some countries with rapid growth in agricultural relative to non-agricultural productivity improve their comparative advantage in agriculture sufficiently to prevent their agricultural sectors from declining in relative terms? The purpose of this paper is to use standard theory and empirical realities 0169-5150/87/$03.50 © 1987 Elsevier Science Publishers B.V. 196 TABLE 1 The declining importance of agriculture, 1960 to 1981 GDP Employment Exports Relative labour productivity in agriculture Low-income countries 1960 1981 48 37 77 73 70 31 0.62 0.51 Lower middle-income countries 1960 1981 36 22 71 54 76 39 0.51 0.41 Upper middle-income countries 1960 1981 18 10 49 30 46 18 0.37 0.33 6 3 18 6 23 15 0.32 0.52 Share of agriculture (%) in Industrial market economies 1960 1981 "Agriculture's share of GDP divided by its share of employment. Source: World Bank (1983, 1984, 1985). to explain why agriculture tends to decline even for economies able to retain a strong comparative advantage in agriculture. The evidence of decline The relative decline of agriculture is clear from both cross-sectional and time-series data for the major country groupings shown in Table 1. The negative relationships between agriculture's shares of gross domestic product ( G D PSH), employment ( EMPSH) and exports ( EXPSH) on the one hand, and income per capita ( YPC) on the other, are very significant statistically. These shares are also negatively associated with population density per unit of agricultural land ( PD), although significantly so only for EXPSH. This is clear from the following OLS regression equation estimates, which are based on World Bank data for 1981 for 70 countries with populations in excess of 1 million ( t-values in parentheses): GDPSH = 87 9.2ln YPC ( 6.7) EMPSH= 179 18.5ln YPC (16.6) 197 A'" Food F' F" 0 M B M' B'" M" B' B" Manufactures Fig. 1. The world (or closed) economy. EXPSH = 152 - 9.5ln YPC ( 5.1) 8.5ln PD ( 4.7) The measured rates of decline in agriculture's importance would be even faster were it not for the fact that low-income countries tend to underprice agricultural products while high-income countries tend to overprice them. Reasons for agriculture's relative decline GOP share To understand why agriculture declines, it is simplest to proceed in stages, beginning with the GD P share. Consider first the global (or a closed) economy producing with available resources only two final goods, food (F) from the agricultural sector and non-food manufactures (M) from the rest of the economy. If AB in Fig. 1 represents the production possibility frontier for the economy in the first period and U a consumption indifference curve, then tangency point E will be the point of equilibrium where supply equals demand for both goods. The equilibrium price ratio is the slope of price line 1. Suppose that with economic growth the production possibility curve moves out equi-proportionately. Then because the income elasticity of demand for food is less than one (Engel's Law), the new equilibrium pointE' will be to the southeast of the ray OE extended and the new price line 2 will be steeper 198 than price line 1 (assuming, as is reasonable, that the shift in the production possibility curve is not solely due to population growth, so that per capita income rises). That is, the ratio of food to non-food production falls and so too does the ratio of food to non-food prices. Hence agriculture's share of GDP must fall as a result of this pattern of economic growth (where GDP is the summed product of price and quantity for the two sectors in this simple model with no intermediate inputs). If non-food manufactured goods are the numeraire and pis the price of food in terms of manufactures, then from Fig. 1 gross domestic product in this model increases from Fp + M to F'p' + M', where ' indicates the new quantities and price ratio. Since M/F < M' /F' andp> p', agriculture's share ofGDP decreases from Fp/ (Fp+ M) to F'p' / (F'p' + M') or, equivalently, from 1/ (1 + M/Fp) to 1/ (1 + M' /F'p'). Under what circumstances would the GDP share of this economy's food sector expand with economic growth? There are two extreme possibilities, both shown in Fig. 1. One involves productivity growth being heavily biased in favour of non-food, as with a shift to E"; the other involves the opposite extreme condition, as at E "'. In both cases the sectoral productivity bias has to be sufficiently extreme for the effect on the price ratio to more than offset the opposite effect on relative quantities ofF and M. In terms of Fig. 1, the pointE" and the slope of price line 3 would need to be such that M/Fp> M" /F"p". Since M/F < M' /F' < M" /F", a very large increase in the price of food relative to non-food- that is, a very skewed shift in the production possibility curve in favour of non-food- would be required to prevent agriculture's share of GDP from falling as this economy grows. Even if there were to be no productivity growth in agriculture, it is still possible that the skewed effect of income growth on demand could outweigh the skewed effect of productivity growth on supply so that the price of food relative to non-food, and hence agriculture's share of GDP, falls in this growing global (or closed) economy. The other extreme case, atE"', seems even less likely: if growth were to be sufficiently biased in favour of the food sector to ensure a new equilibrium at E 0 on the ray OE extended, for example, so that the relative quantities ofF and M produced were the same as at E, the lower relative price of food at E 0 would still ensure a drop in the food sector's share of GDP. That is, E "' has to be even further to the northwest corner of Fig. 1 than E 0 • Two reasons can be given as to why an outcome such as E"' is unlikely. One is that since agriculture typically is the more labour-intensive sector of a developing country, the accumulation of capital per worker as economic growth proceeds will tend to encourage expansion ofthe more capital-intensive sector at the expense of the more labour-intensive sector. This is a standard trade theorem due to Rybczynski (1955). The second reason is based on an empirical observation. While the empirical evidence on the long-run trend in the price of primary products relative to manufactures is still subject to debate, partie- 199 200 150 100 75 1900 1910 1920 1930 1940 1950 1960 1970 1960 Fig. 2. Real international prices of agricultural products, 1900-1985 (1979-81 = 100). Weighted average of international prices in US dollars for grains, livestock products, sugar, beverages, vegetable oils, bananas, fibres, rubber, tobacco, hides and skins, and timber, deflated by the qualityadjusted US producer price index for industrial goods, with weights based on the share of each commodity in the value of world trade in 1979-81. When the logarithm of this relative price index (P) is regressed against time ( T), the equation obtained is P= 0.25-0.0051 T UP= 0.48; tvalue= -8.8). (Compiled by the author from data provided in Grilli and Yang (1986) and supplemented with updated data from World Bank files for which the author is indebted to M.C. Yang.) A, Food A" A I I F' ------+---1 I I I 0 B" M Manufactures Fig. 3. A small, open economy. ularly on the extent to which quality adjustments have been made to available price indexes of manufactured goods, the weight of evidence seems to support the view that agricultural prices have declined relative to industrial product prices (see, for example, Spraos, 1980; Sapsford, 1985; Grilli and Yang, 1986). One comprehensive series, developed by the World Bank for the period 1900-1985, is shown in Fig. 2. The rate of decline is slightly faster if beverages are excluded, and slightly slower if non-food agriculture is excluded, but in all 200 cases the estimated coefficients for the time variable in the log-linear regression equations are significantly less than zero at the 0.1% level. Together these observations suggest that outcomes to the northwest of E 0 such as E"' in Fig. 1 are most unlikely, and so will be ignored. The above model is appropriate for the world economy as a whole, and for a closed national economy. Consider now a small country in an open global economy, with again only two sectors producing the tradable products F and M. Suppose that economic growth in the rest of the world is not strongly biased against agriculture, so the international price of food relative to manufactures is falling as Fig. 2 suggests. If there is no growth in this small country then the decline internationally in the relative price of food from p to p' will result in a decline in the share of agriculture in this economy's GDP. This is clear from the movement from E to E' in Fig. 3, since both the price and the quantity of food relative to manufactures fall. What if this small economy is also growing? If its growth is such that the production possibility curve moves out equi-proportionately, then agriculture's share of GDP must still decline. This is because in Fig. 3 F" /M" would then equal F' /M' ( <F/M) and, since p' is still the ruling international and domestic price ratio, it follows that 1/ (1 + M/Fp) > 1 (1 + M" /F"p'). Only if the shift in this country's production possibility curve is skewed in favour of agriculture, such as from AB to A"' B"', would it be possible for the increase in production of food relative to manufactures to more than offset the decrease in the relative price of food. Three points are thus worth stressing so far. First, in a growing world economy (or a closed national economy) agriculture's share of total product is likely to decline because the income elasticity of demand for food is less than one. Only if the expansion in production possibilities is heavily biased towards non-agriculture is it possible that the price of food relative to other goods will rise - and even then this price change may not be sufficient to offset the opposite change in relative production levels and thereby increase agriculture's share of total product. Second, in a small open economy faced with a decline in the relative price of food because of economic growth elsewhere, agriculture's share of GDP will fall unless growth in this economy is biased in favour of agriculture (unlike for the world economy as a whole). The pro-agricultural bias in its growth (or in its price distortions - see below, "some qualifications") would have to be greater for agriculture's share of national product not to decline, the larger the fall in the relative price of food internationally. And third, the pattern ofdomestic consumption in this model with only two tradable goods is not relevap.t in determining the production pattern in the small open economy, again in contrast to the situation for the world economy as a whole; however, as will become clear below, domestic consumption does affect the trade pattern. In reality, a large part of each economy involves the production and con- 201 sumption of non-tradable goods and services ( N). These are items for which the costs of overcoming barriers to trading internationally (especially transport costs) are prohibitively expensive. If it can be shown that the share of tradables in GDP declines with economic growth, then this increases the likelihood even more that agriculture's share of GDP will decline in growing economies. To examine this possibility, combine the F and M sectors into a super-sector of tradables, T. The price ofT for our small open economy is given by the international prices ofF and M. The price of non-tradables (N), however, is determined by domestic demand and supply conditions because, in equilibrium, domestic demand for non-tradables has to equal domestic supply. Given that the non-tradables sector is roughly equivalent to the services sector (some services are tradable but some goods are non-tradable), and that services account for about one-third of expenditure in low-income countries and two-thirds in high-income countries, it is reasonable to assume that the income elasticity of demand for non-tradables exceeds one, and hence the corresponding elasticity for all tradables (including food) is less than one. [ Lluch et al. (1977, table 3.12) obtained estimates of expenditure elasticities in the range 1.3-1.8 for major groups of services. More recent cross-sectional studies support the expectation of an income elasticity of demand for services of well above unity for low-income countries but gradually approaching unity as countries get richer ( Kravis et al., 1983; Summers, 1985).] Figure 1 can be used to illustrate what happens when a small open economy with a tradables sector grows, if on the axes F is replaced by T and M by N. Then E is the initial equilibrium point (when demand for and supply of nontradables are equated) and price line 1 represents the initial price of nontradables relative to tradables. Now assume the price ofT remains unchanged for the moment but there is economic growth which shifts out the production possibility curve. If the curve moves out equiproportionately from AB to A' B' then necessarily both the price and quantity of non-tradables relative to tradables must increase (a real exchange rate appreciation), given that E' must be to the southeast of the ray OE extended because of the income effect. That is, tradables contribute a declining proportion of GDP in an economy whose productivity growth is not sectorally biased but whose consumption growth pattern is biased against tradables. As with the earlier discussion of the global economy without non-tradables, there are two extreme sets of circumstances in which, conceptually, the nontradables sector of a growing economy would not expand its share of GDP. One is represented by point E", the other by E "'. To reach E", growth would have to be heavily biased in favour of non-tradables production and the elasticity of substitution in consumption between T and N low for the relative price of nontradables to fall sufficiently to offset the increase in production of non-tradables relative to tradables. Alternatively, to reach E"' growth would have to be 202 heavily biased in favour of tradables production and again the elasticity of substitution in consumption between T and N low for the relative price ofnontradables to rise sufficiently to offset the decrease in production of non-tradables relative to tradables. The first possibility seems most unlikely, given that productivity growth has, if anything, been biased against the non-tradables sector (Clark, 1957). The second possibility is less remote, but recall that it requires an extreme bias in productivity growth against non-tradables to offset the consumption bias in favour of tradables: it is not sufficient, for example, to be only biased enough for point E 0 to be attained. Thus, since agriculture's share ofthe tradables part ofGDP is likely to decline, and the tradables' share of GDP is also likely to fall, introducing a non-tradables sector into the model to make it more closely represent a real economy makes it even more likely that agriculture's share of GDP will decline with economic growth. Employment share The above reasoning is also sufficient for explaining the decline in agriculture's share of employment, except in cases where agricultural labour productivity grows extremely slowly relative to labour productivity in other sectors. Where labour productivity is growing more rapidly on farms than in non-farm jobs, as appears to have been the case in industrial countries during recent decades (Table 1) , there is even more reason to expect agriculture to become a less important employer. In fact, the number of people employed on farms in industrial countries has declined absolutely, the rate of decline averaging 2.8% per year during the period 1960-1981 (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, 1983). Export share Why is agriculture's share of exports less strongly correlated with per capita income than is agriculture's share of GDP or employment, as shown in the above regression equations? Consider again a small economy within an open global economy in which the international price of food relative to other tradables is declining over time because productivity growth in the rest of the world is not strongly enough biased against agriculture to offset the effect of a relative decline in food demand. If this small economy is not growing, then clearly the share of agriculture in exports will decline: the price change would discourage domestic food production and encourage domestic food consumption, while the opposite would occur in the domestic market for non-foods. If this small economy is growing and if its productivity growth is sectorally unbiased, then this tendency for agriculture's share of exports to fall would be weakened because domestic demand would grow less rapidly for food than for non-food. And it 203 would be weakened further if productivity growth grew faster in agriculture than non-agriculture in this small economy. Thus it is understandable that the share of agriculture in exports is less strongly (negatively) correlated with per capita income than agriculture's shares of GDP and employment. A negative relationship nonetheless is likely, both for economies which are growing only slowly and, especially, for economies where productivity growth is fastest in the industrial sector; a positive relationship will occur only for those economies where productivity growth in agriculture is sufficiently greater than in manufacturing so as to be able to generate additional food export volumes to more than offset the long-term decline in the real international price of food. Note, however, that a declining contribution to the country's exports from agriculture does not necessarily imply a declining agricultural comparative advantage as revealed by the pattern of its export specialisation. This is because agriculture's importance in world trade may be falling even faster than its importance in this country's exports. Some qualifications The above discussion has abstracted from the fact that many economies seriously distort incentives faced by producers and consumers. In particular, it is common for low-income economies to tax agriculture relative to manufacturing, for high-income (especially food-deficit) economies to subsidise agriculture relative to manufacturing, and for growing economies to gradually change from the former to the latter as they industrialise. [See, for example, Little et al. (1970), Balassa et al. (1971), Anderson and Hayami (1986) and Tyers and Anderson (in press). The latter two studies also suggest reasons for the growth of agricultural protection in industrialising countries.] Any one economy following this pattern after having taxed agriculture would slow the pace of decline of its agricultural sector, both because of the direct effect of price changes on sectoral output levels and on their changing per unit valuation at distorted domestic prices, and because ofthe indirect effect those changes have in boosting investments in new farm technology. Indeed the latter can be large enough to actually reverse the economy's net food trade position, as has been the case in Western Europe and China during recent years. When many economies conform to this distortions pattern simultaneously, the effect on international food prices depends on the proportion of world food markets that is low priced as compared with the proportion that is high priced. Over time, however, as each economy industrialises and so moves towards the agricultural protection camp, the net effect will be to add to the downward pressure on the international price of food relative to other tradables. As a result, the agricultural sector of undistorted economies will be under pressure to decline even faster than would be the case in a distortion-free world. The above models have also ignored the fact that intermediate goods and 204 TABLE2 Value added share (%) of agricultural (manufacturing) production measured at domestic prices, Industrial Market Economies, 1963-1983" Australia Austria Canada EC-IOb Japan Korea New Zealand Norway Sweden Taiwan United States Weighted averagec 1963-65 1970-73 38 (41) 33 70 38 57 62 80 63 52 54 56 43 49 43 65 (39) (33) 59 55 64 42 48 (40) (39) (44) (46) (40) (40) (40) (33) (41) (34) (39) (38) (37) (38) (46) (41) 1975-78 33 68 29 51 62 77 53 52 53 54 37 43 (42) (37) (33) (40) (32) (36) (33) (31) (37) (43) (41) 1980-83 30 66 22 46 54 67 45 50 48 50 34 39 (38) (35) (33) (39) (30) (33) (33) (28) (34) (42) (38) "Manufacturing sector shares are shown in parentheses; in the final column they refer only to 1980. Because of different statistical methods used, shares are not as comparable across countries as they are over time for each country. bWeighted average for France, Federal Republic of Germany and the United Kingdom for manufacturing shares, with weights based on 1980 value of manufacturing production. cweights based on 1980 value of agricultural (manufacturing) production at domestic prices. Source: Manufacturing data are from United Nations (1985a, b and earlier issues). Agricultural data for Austria, Japan, Norway and Sweden are from United Nations (1985a and earlier issues), for the European Community are from Eurostat (1985 and earlier issues) and for other countries are from the following national sources: Australian Bureau of Agricultural Economics (1986), Agriculture Canada (1980 and 1984), Korean Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries (1981 and 1985), New Zealand Department of Statistics (1985 and earlier issues), Council for Economic Planning and Development (1985), Department of Agriculture and Forestry (1985 and earlier issues) and U.S. Department of Agriculture (1984 and earlier issues). services are used in the production process. To include them requires two modifications. One is to recognise that agriculture's share of GDP then refers to a percentage of value added rather than of total value of production. This would not matter if the value-added share of output was constant or changed at the same rate in each sector. But, as Table 2 shows, that share has been declining much more rapidly in agriculture than in manufacturing: during the two decades to 1983, the share for industrial countries declined from 48 to 39% for agriculture but only from 40 to 38% for manufacturing, measured at domestic prices. [The relative decline in agriculture's share would have been even greater if measured at international prices, given the gradual growth in agricultural protection mentioned above.] This adds to the reasons for the decline in agriculture's share of GDP. The second modification is to consider the sectoral source of intermediate goods and services. Casual empiricism suggests the nonfarm sectors traditionally have supplied a disproportionately large and 205 increasing share of those inputs, so this again strengthens the expectation of a decline in agriculture's share of GDP. Throughout, the discussion has used the term food to describe agricultural output. While non-food agricultural products are slightly different in that the income elasticity of demand for them is not necessarily below one and falling, they are relatively small contributors to total agricultural output, so the conclusions are unlikely to be altered if they had been specifically included in the analysis. Conclusion This analysis allows the following conclusions to be drawn. First, in a growing world economy (or a closed national economy), agriculture's shares of GDP and employment are likely to decline because the income elasticity of demand for food is less than one; to avoid this would require a heavy bias in productivity growth towards the non-farm sector. A corollary is that the world price of food relative to non-food is likely to decline with global economic growth. Second, in a small open economy faced with a decline in the relative price of food because of economic growth elsewhere, agriculture's shares of GDP, employment and exports are likely to decline. This is so even if this small economy is itself not growing, because of the decline in international food prices. If it is growing, then agriculture's shares of GDP and employment, if not of exports, are even more likely to decline because of the low domestic income elasticity of demand for food. To avoid declining requires either a strong bias in productivity growth towards the farm sector (in contrast with the global or closed economy case) and/ or a heavy distortion of incentives towards agriculture. Experience suggests that even then the decline in agriculture's shares of GDP and employment are unlikely to be arrested: Western Europe and China provide recent examples of reversing the downward trend in agriculture's share of exports, but not GDP and employment, through price policy changes which improved incentives for farmers. Third, the fact that many countries tend to distort incentives increasingly in favour of farmers as their economies industrialise, which further depresses the real international price of food, only adds to the likelihood of agriculture declining in undistorted economies. Finally, it should be stressed that it does not follow from this analysis that farmers necessarily lose from economic growth. Part of the reason for declining real food prices is increased productivity on farms, and part of the reason for labour moving out of agriculture is improved income-earning prospects in nonfarm sectors. Thus farm households may well be sharing in the fruits of economic growth either through new farm technologies which raise farm labour and land productivity and/or through household members taking higher-pay- 206 ing jobs in other sectors. Nor does it follow that policies should be adopted to accelerate resource movements away from the declining agricultural sector. On the contrary, the policy response advocated by Prebisch (1964) and others to declining terms of trade for countries exporting primary products, namely, protecting the import-competing manufacturing sector so as to divert resources away from primary production, would only make things worse for farmers and the total economy, as it would worsen the domestic terms of trade for nonmanufacturing sectors as well as reduce national income and hence non-farm job prospects for farm household members. References Agriculture Canada, 1980, 1984. Selected Agricultural Statistics for Canada. Ottawa. Anderson, K. and Hayami, Y., 1986. The Political Economy of Agricultural Protection: East Asia in International Perspective. Allen and Unwin, Sydney. Australian Bureau of Agricultural Economics, 1986. Commodity Statistical Bulletin. Australian Government Publishing Service, Canberra. Balassa, B. and Associates, 1971. The Structure of Protection in Developing Countries. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, MD. Clark, C., 1957. The Conditions of Economic Progress. Macmillan, London, 3rd edn. Council for Economic Planning and Development, 1985. Taiwan Statistical Data Book. Taipei. Department of Agriculture and Forestry, 1985. Taiwan Agricultural Yearbook. Taipei. Eurostat, 1985. Yearbook of Agricultural Statistics. Brussels. Grilli, E.R. and Yang, M.C., 1986. Long-term Movements of Non-fuel Primary Commodity Prices: 1900-83. Economic Analysis and Projections Department, The World Bank, Washington, DC (mimeograph) . Johnson, D.G., 1973. World Agriculture in Disarray. Fontana, London. Korean Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries, 1981, 1985. Yearbook of Agriculture and Forestry Statistics. Seoul. Kravis, I.B., Heston, W. and Summers, R., 1983. The share of services in economic growth. In: F.G. Adams and B.G. Hickman (Editors), Global Econometrics. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA. Kuznets, S.S., 1966. Modern Economic Growth: Rate, Structure and Spread. Yale University Press, New Haven, CT. Little, I., Scitovsky, T. and Scott, M., 1970. Industry and Trade in Some Developing Countries: A Comparative Study. Oxford University Press (for OECD), London. Lluch, C., Powell, A.A. and Williams, R.A., 1977. Patterns in Household Demand and Savings. Oxford University Press, New York. New Zealand Department of Statistics, 1985. Official Year Book. Wellington. Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, 1983. Historical Statistics 1960-1981. OECD, Paris. Prebisch, R., 1964. Towards a New Trade Policy for Development. United Nations, New York. Rybczynski, T.M., 1955. Factor endowments and relative commodity prices. Economica, 22: 336-341. Sapsford, D., 1985. The statistical debate on the new barter terms oftrade between primary commodities and manufactures: A comment and some additional evidence. Econ. J., 95: 781-788. Schultz, T.W., 1945. Agriculture in an Unstable Economy. McGraw-Hill, New York. 207 Spraos, J., 1980. The statistical debate on the net barter terms of trade between primary commodities and manufactures. Econ. J., 90: 107-128. Summers, R., 1985. Services in the International Economy. In: R.P. Inman (Editor), Managing the Service Economy. Cambridge University Press, New York, pp. 27-48. Tyers, R. and Anderson, K., (in press). Distortions in World Food Markets. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. United Nations, 1985a. National Accounts Statistics: Main Aggregates and Detailed Tables. United Nations, New York. United Nations, 1985b. Statistical Yearbook. United Nations, New York. U.S. Department of Agriculture, 1984. Economic Indicators of the Farm Sector. USDA, Washington, DC. World Bank, 1983, 1984, 1985. World Development Report. Oxford University Press, New York.