* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Download paper (PDF)

Fiscal multiplier wikipedia , lookup

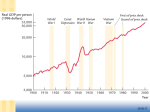

Economic growth wikipedia , lookup

Business cycle wikipedia , lookup

Rostow's stages of growth wikipedia , lookup

Fei–Ranis model of economic growth wikipedia , lookup

Early 1980s recession wikipedia , lookup

Full employment wikipedia , lookup

Refusal of work wikipedia , lookup