* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Progress in developing and implementing stepped-care psychological support for people with psoriasis

Psychiatric and mental health nursing wikipedia , lookup

Emergency psychiatry wikipedia , lookup

Mental health professional wikipedia , lookup

Moral treatment wikipedia , lookup

History of psychiatric institutions wikipedia , lookup

Victor Skumin wikipedia , lookup

Controversy surrounding psychiatry wikipedia , lookup

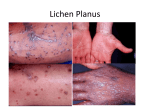

Practice DEVELOPMENT Progress in developing and implementing stepped-care psychological support for people with psoriasis Mark A Turner, Lucy Moorhead, Anna Simpson, Karina Jackson Abstract Psoriasis is an inflammatory, chronic, skin condition that can bring about significant difficulties in physical, psychological and social functioning. The need for people with this skin condition to be assessed and treated with an approach to care accounting for the mind and body is becoming increasingly recognised in research and current policy. This article shares how one specialist centre collaborated with a South London-based project to develop and implement systematic screening and various care pathways to support people with psoriasis, psychological distress and problems in coping. The work described includes a ‘stepped-care’ service model of psychological support drawing from existing and newly developed resources. The article also includes reflections for nursing and recommendations for dermatology services. Key words Psoriasis Psychological distress Screening Stepped-care service model Care pathways Introduction Psoriasis is an inflammatory, chronic skin condition involving erythematous, scaly plaques that can affect any skin surface; most commonly the knees, elbows, scalp and buttocks in a symmetrical fashion. It Dr Mark A Turner is a Highly Specialist Clinical Psychologist, Lucy Moorhead is a Clinical Nurse Specialist and Karina Jackson is a Nurse Consultant at St John’s Institute of Dermatology, Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, London. Anna Simpson is a Project Coordinator at Integrating Mental and Physical Healthcare: Research Training and Services, King’s College, London 22 affects up to 3% of the population with its most common age of onset being before 40 years of age, and men and women are affected equally (Menter et al, 2008). Many people with this condition also develop co-morbidities such as psoriatic arthritis and metabolic syndrome (Christophers, 2007). However, psoriasis can cause a significant impairment in quality of life across physical, psychological and social functioning (de Korte et al, 2004). Indeed, the burden of psoriasis goes well beyond the physical and there is an increasing awareness that people with this skin condition require their assessment and treatment to be more ‘holistic’, accounting for the mind and body. Research, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance, recommendations from the British Association of Dermatologists (BAD) and parliamentary policy (ie, the All Party Parliamentary Group on Skin, 2013) all highlight the need to address psychosocial distress in people with psoriasis. Dermatological Nursing, 2015, Vol 14, No 2 The purpose of this article is to illustrate how one dermatology centre has responded to this progressive agenda. We will outline the process adopted for the systematic screening of psychological difficulties in our psoriasis service and the corresponding steppedcare pathways, considering the role of the nurse in the team approach. A follow-on article will share data on the prevalence and type of psychological distress revealed through the screening process. Psoriasis and psychological distress It has been shown that more than 10% of people with psoriasis have clinical depression and twice as many have depressive symptoms (Dowlatshahi et al, 2014). It has also been known for some time that one in four people with psoriasis report having experienced suicidal ideation at some point in their life because of their skin condition (Rapp et al, 1997) and around 40% experience high levels of anxiety (Richards et al, 2001). Furthermore, research shows that levels of anxiety, depression and worry do not necessarily decrease www.bdng.org.uk Practice DEVELOPMENT following successful medical treatment for psoriasis (Fortune et al, 2004). Data also exists demonstrating that the extent to which people with psoriasis are psychologically distressed is not related to more objective ratings of the severity of their skin condition (Kimball et al, 2004; Sampogna et al, 2004). Research also suggests that psychosocial difficulties or stressors can induce the onset and exacerbation of psoriasis, perhaps more so than in people with other skin conditions (AlAbadie et al, 1994; Schmid-Ott et al, 2009) and impede the effectiveness of its medical treatment (Fortune et al, 2003). Furthermore, there is some evidence that psychological intervention as an adjunct to medical treatment can reduce psoriasis severity and improve psychological wellbeing or dermatologyrelated quality of life, relative to medical treatment alone (Fordham et al, 2014; Fortune et al, 2002; Kabat-Zinn et al, 1998). However, it has been shown that only 39% of significantly distressed psoriasis patients have psychological difficulties raised by their dermatologist in routine consultations (Richards et al, 2004). Therefore we believed that the adoption of a systematic approach to appropriately identify the psychological needs of people with psoriasis would improve holistic assessment. We also recognised that such identification would require us to devise care pathways offering psychological support, which are described hereafter. NICE guidance relevant to psoriasis Clinical guidelines (NICE, 2012) on the assessment and management of psoriasis recommend that the impact of this skin condition on physical, psychological and social wellbeing should be routinely assessed, including impact on mood and levels of distress. The same guidelines recommend that people with psoriasis are provided with information and support including strategies to deal with the impact on their psychological wellbeing. Assessing the impact of psoriasis on the person is also one of six quality standards agreed for national adoption (NICE, 2013). More broadly, www.bdng.org.uk NICE guidance on the treatment of common mental health problems (NICE, 2011) and on treating depression in adults with a long-term physical health problem (NICE, 2009) both promote the use of a ‘stepped-care’ approach in which the level of intervention and healthcare professional expertise is matched to clinical need. NICE (2009) has suggested the following steps: Step 1; The recognition, assessment and initial management of all patients through the use of screening questions, a validated measure, and advice and increased contact with practitioners, if necessary. Step 2; For people with recognised depression, including persistent subthreshold depressive or mild to moderate depression, increased levels of advicegiving, monitoring and contact with practitioners and the option of ‘lowintensity’ psychological interventions (eg, group-based peer support or individually guided self-help based on Cognitive Behavioural Therapy; CBT) should be offered. Step 3; For people with recognised depression (as above) with inadequate response to initial interventions and moderate and severe depression — discuss the option of antidepressant medication or ‘highintensity’ psychological interventions (eg, individual or group-based CBT) for initial presentations of depression and a combination of these treatment modalities for severe depression. Step 4; For people with complex and severe depression, contact with specialist mental health services working closely and collaboratively with the physical health services should be used. British Association of Dermatologists (BAD) working party report The importance of offering stepped care, specifically within the dermatology setting, has been put forward by the BAD working party report on minimum standards for psychodermatology services (Bewley et al, 2012). This stepped-care service model strongly encourages the involvement of dermatologists and dermatology nurses for offering psychological support at level 1 (Figure 1). The suggested level 2 support for people who are moderately distressed involves patient contact with psychotherapy/CBT subsequent to contact with a psychodermatology multidisciplinary team (MDT). The level 3 support, for people who are highly distressed and those with primary psychiatric needs, suggests referral to a regional psychodermatology service. One of the main recommendations from this report is that psychological support remains largely embedded within the dermatology setting and this is in keeping with what has been suggested for stepped-care support by other experts working in the field of psychodermatology (Thompson, 2009, 2014a, b). Methods adopted in psoriasis clinic In our centre we grasped the opportunity to team up with a South London-based project called ‘IMPARTS’. Standing for Integrating Mental and Physical Healthcare: Research Training and Services, IMPARTS is a project that assists physical health settings like dermatology or rheumatology departments to screen for psychological problems in their respective patient populations. The IMPARTS project provides advice on the selection and development of screening tools for each specialist department. IMPARTS also helps the physical health team to devise and implement the most appropriate and integrated care pathways for their patients while offering IT support. The IMPARTS team package is completed with staff training in topics relevant to psychosocial distress and the development of bespoke selfhelp material to promote improved psychological coping in specialist areas. Screening tools selected There is a range of validated psychological health-screening questionnaires available to use in practice. We selected the patient health questionnaire depression scale (PHQ9) and the generalised anxiety disorder scale (GAD-7). The PHQ-9 and GAD7 were used so that we could ‘talk the same language’ as Primary Care Psychology and General Practice services who are both used to using these questionnaires for regular monitoring and outcome assessment. These tools Dermatological Nursing, 2015, Vol 14, No 2 23 Practice DEVELOPMENT be marked as not relevant by the patient and in these cases such items are scored as 0. Quality-of-life cut-off scores on the DLQI are: 0-1 (no effect), 2-5 (small effect), 6-10 (moderate effect), 11-20 (very large effect), and 21-30 (extremely large effect). Dermatology patient Initial assessment in dermatology clinic Low level distress Moderate level distress High level distress and primary psychiatric disease eg delusional infestation/suicidal Psychological support Level 1 skills Dermatologist/Dermatology nurse Psycho-dermatology Multi-disciplinary team Risk assessment Psychologist Dermatologist Psychiatrist Regional psychodermatology service Level 3 skills Dermatologist Psychologist Psychiatrist Psychotherapy/CBT Level 2 skills Figure 1. The stepped-care provision of psychodermatology services from the BAD working party report (Bewley et al, 2012). are also NICE recommended for screening physical health patients. We also continued to use the dermatology life quality index (DLQI) Patient Health Questionnaire depression scale (PHQ-9) The PHQ-9 is a reliable and valid 9-item self-report questionnaire that measures symptoms of depression experienced in the last two weeks (Kroenke et al, 2001). It belongs to the patient health questionnaire, which is an instrument for diagnosing mental health problems commonly found in primary care (Spitzer et al, 1999). Scores for each item of the PHQ-9 range from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day) and so the measure’s full range is 0-27 with the following symptom severity cut-off scores: 5 (mild), 10 (moderate), 15 (moderatesevere) and 20 (severe). 24 Generalised Anxiety Disorder scale (GAD-7) The GAD-7 is a reliable and valid 7-item self-report questionnaire that measures symptoms of anxiety experienced in the last two weeks (Spitzer et al, 2006). Scores range from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day) for each item of the GAD-7 and so the measure’s full range is 0-21 with the following symptom severity cut-off scores: 5 (mild), 10 (moderate), 15 (severe). Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) The DLQI measures quality of life specifically related to living with a skin condition. It is widely used for both clinical and research purposes and has adequate validity and reliability (Finlay, Khan, 1994). It has 10 items, each of which is scored using the range 0 (not at all/no) to 3 (very much or ‘yes’ in the case of item 7) and so the measure’s full range is 0-30. Eight items can also Dermatological Nursing, 2015, Vol 14, No 2 Electronic screening The selected questionnaires were offered on an electronic tablet device (iPad) to all patients attending the specialist tertiary psoriasis clinic at each attendance. Patients were initially given an information sheet about the content and use of the questionnaires as a means of gathering informed consent. An opt-out rather than opt-in consent process was adopted because the work was routine clinical practice, as opposed to research. Clinic nurses also confirmed that the patients were able to use the tablet device as well as read and understand the questionnaires’ items. If the patient required assistance, due to English not being their first language, unfamiliarity with the device and/or physical disabilities, the patient was invited to a quieter area and offered assistance to maintain privacy and dignity. Patients completed the PHQ-9, GAD-7 and DLQI questionnaires at every clinic visit prior to seeing the clinician. The questionnaire data collected was available almost instantaneously on the patient’s electronic patient record. The speed of this system enabled clinicians to review the results prior to their consultation with patients and address any relevant issues within it. In the rare instances that a patient declined to complete the iPad’s questionnaires we offered a paper DLQI solely to be completed during their consultation. Interpreting the questionnaire data The interpretation of screening data was in keeping with a protocol collaboratively made with the IMPARTS team. This protocol included algorithms that converted scores from the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 into referral advice based around what was most likely to be clinically meaningful, in keeping with the stepped-care model described www.bdng.org.uk Practice DEVELOPMENT www.bdng.org.uk Dermatological Nursing, 2015, Vol 14, No 2 25 Practice DEVELOPMENT Table 1. Referral advice corresponding to cut-off scores on the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 used in the IMPARTS integrated care pathways. In our protocol, referral advice for depression was only shown for those who screened positive for ‘Probable Major Depression’ on the PHQ-9. Suicidal ideation was defined as a score of ‘2’ or ‘3’ on item 9 of the PHQ-9 and this was always followed with additional questions and appropriate actions, such as urgent contact with liaison psychiatry, if necessary. Name of tool Cut-off scores used in protocol Referral advice Patient Health Questionnaire depression scale (PHQ-9) Suicidal ideation AND severe depression (PHQ-9 = 20-27) Urgent referral to liaison psychiatry/ phone GP Suicidal ideation OR severe depression Referral to liaison psychiatry/ (PHQ-9 = 20-27) phone GP Generalised Anxiety Disorder scale (GAD-7) Moderate depression (PHQ-9 = 15-19) Team clinical psychologist OR alert GP and advise IAPT Mild depression (PHQ-9 = 9-14) Alert GP in letter; advise IAPT referral Severe anxiety (GAD-7 ≥15) Team clinical psychologist Mild to moderate anxiety (GAD-7 = 10-14) Alert GP in letter; advise IAPT referral Dermatology patient Step 1: Screening AND staff recognition of reduced quality of life/problems in coping/emotional health difficulties Step 2: Peer support and self-help Referrals to IAPT Step 3: Team psychologist Inside GSTT general hospital setting Step 4: Urgent and non-urgent referrals to liaison psychiatry Outside GSTT general hospital setting Figure 2. The flexible stepped-care service model of psychological support developed and being implemented in Medical Dermatology and more specifically the psoriasis clinic at Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust (GSTT). below. See Table 1. It is important to note that the referral advice generated from the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 was never the sole source of information upon which referrals were made. Specific referral advice was not generated from the DLQI, although its results were still displayed electronically and used in parallel to assist overall interpretation. A clinical psychologist was recruited to support and work 26 alongside the dermatology clinical team. The psychologist assisted the nursing and medical team to interpret the questionnaire data and identify people with psoriasis presenting with problems in coping and/or psychological distress. The knowledge and skill of the medical and nursing team to identify and act upon identified psychological distress was achieved with regular multidisciplinary discussion and brief consultations with the psychologist Dermatological Nursing, 2015, Vol 14, No 2 in the psoriasis clinic. Management plans were formed using several care pathways, as part of our stepped-care model. One of the key distinctions informing these plans was the extent to which psychological distress was related to coping with psoriasis or unrelated psychosocial difficulties. Our flexible stepped-care service model of psychological support In order to support those people identified with psychological difficulties in our psoriasis clinic, we have developed and are implementing the stepped-care service model of psychological support shown in Figure 2. The model is in keeping with stepped care as outlined in NICE guidelines (NICE, 2009) and we refer to it as ‘flexible’ further to its use of care pathways both inside and outside of the hospital setting to which our tertiary psoriasis clinic belongs. The decision to use such care pathways was made further to the extent of the unmet need in our department in the context of having only one team psychologist, the reality of having many patients who live too far away to return for regular psychological therapy, and the nationwide availability of support in primary care psychology, namely ‘Increasing Access to Psychological Therapies’ (IAPT) services. The model nonetheless includes psychological support in the dermatology department (Bewley et al, 2012) at steps 1–3, in keeping with guidance from Thompson (2009). Step 1: Recognition and handling Our step 1 includes the routine use of screening for reduced dermatology-related quality of life and emotional health difficulties each time a person with psoriasis attends the outpatient clinic. This screening has also been supported by staff training on topics such as ‘identifying anxiety and depression in people with psoriasis’ and ‘Introducing IAPT’ and the team psychologist’s presence in every psoriasis clinic. Such work has optimised the recognition and handling of emotional health difficulties and problems in coping specific to people living with psoriasis; it has also www.bdng.org.uk Practice DEVELOPMENT supported the use of various care pathways described below. Step 2: Peer support and self-help Peer-support groups and self-help are recognised step 2 methods of intervention delivery (NICE, 2009). More specifically, peer support between people sharing a physical health problem is suggested in this NICE guidance and so we are aiming to develop this form of intervention within our medical dermatology department. Our self-help material is based on a cognitive-behavioural approach (available at: http://www.kcl.ac.uk/ioppn/depts/pm/ research/imparts/Self-help-materials. aspx ). We have tailored the material to the experiences of people with psoriasis and received input from patients and the medical and nursing team to inform the resource. This material, as well as that based on more generic difficulties such as sleep problems, was given to patients as appropriate after consultation with nursing staff or the team psychologist during psoriasis clinic appointments. www.bdng.org.uk Self-help as a method of intervention is important because many patients who do not receive face-to-face psychological therapy might still have at least some symptoms of psychological distress (Dowlatshahi et al, 2014) that should not be left untreated. The widespread provision of self-help interventions requires multidisciplinary involvement and so both medical and nursing staff should be aware of what material is available and where to direct patients to access it (Thompson, 2014a). This has been a key role for our nursing team. Primary care psychology: increasing access to psychological therapies (IAPT) Increasing access to psychological therapies, or ‘IAPT’ services, offers psychological therapy options on a national level. These services can be referred to by GPs and other health professionals, or indeed self-referrals can often be made. IAPT services have also been developed in a stepped-care model and they offer support mainly at steps 2 and 3. The IAPT service makes decisions on who enters each of these steps usually through a telephone triage system. People can be ‘stepped-up’ or ‘down’ according to need. As part of our steppedcare model we routinely advise GPs to refer patients to their local IAPT services. We also give out self-referral telephone numbers that can be found through visiting NHS choices (see: http://www.nhs.uk/Service-Search/ Counselling-NHS-(IAPT) services/ LocationSearch/396). Our rationale for utilising these services in parallel to developing psychological resources in dermatology as part of our model has been mentioned. A further point, however, is that, as of yet, self-help/ computerised methods of intervention cannot be used in substitute for face-to-face delivery (Bundy et al, 2013). We aim to refer people with psychological distress unrelated to their psoriasis to IAPT services. Step 3: Highly specialist clinical psychology In every psoriasis clinic the team psychologist carries out consultations in the form of brief assessments and some Dermatological Nursing, 2015, Vol 14, No 2 27 Practice DEVELOPMENT intervention work. The psychologist’s presence in the psoriasis clinic also allows this member of the clinical team to function as a pivot for the care pathway leading on from step 1. Being embedded in the psoriasis clinic also serves the important purpose of destigmatising contact with psychological services and gives access to patients who would not otherwise come into contact with a psychologist; it also promotes and normalises the mind-body link to this population. This approach may be particularly important in people with psoriasis (and others with skin conditions) due to the high risk of discrimination and stigma they experience. The team psychologist also receives internal referrals from nursing and medical staff in medical dermatology outside of the time spent in the psoriasis clinic. The psychologist carries out specialist assessment and treatment of those referred based on cognitive-behavioural approaches. This work includes the measurement of clinical outcome and patient satisfaction (Bewley et al, 2012). There is an aim to refer people with a complex interaction between their psoriasis, coping, and emotional health into step 3, given the team psychologist’s presence in the multidisciplinary team and special interests. Step 4: Liaison psychiatry In some patients there is a need for psychiatric review and management. Psychiatrists are medically trained doctors specialising in mental healthcare. They therefore have a key role in diagnostic assessment and prescribing as a form of treatment, in addition to holding knowledge of community-based mental health services. Psychiatry plays an important role in the management of potentially suicidal patients. Liaison psychiatry in our hospital setting uses a system including both urgent and non-urgent referrals. For referrals where this system does not match clinical need, psychiatry embedded in accident and emergency and/or community services (often called assessment and brief treatment teams) is 28 utilised. In parallel we also keep general practice up to date. General reflections The implementation of systematic screening for anxiety and depression (in addition to dermatology-related quality of life) through electronic questionnaire surveys has been widely accepted by people attending our psoriasis service, with a decline rate of <5%. The use of technology over paper questionnaires has also been implemented without difficulty. The process has been simplified as this is a clinic specifically for people with psoriasis and the approach in a mixeddiagnosis general dermatology clinic would need further consideration. In our experience, the introduction of systematic screening for psychological distress has led to a number of positive outcomes; the holistic needs of people with psoriasis are being assessed and addressed appropriately as recommended in NICE guidelines; there is improved staff learning and understanding with a corresponding reported increase in confidence and competence in addressing patients’ psychological needs; there is also a better understanding of the range of psychological interventions and support services available. These changes have led to more appropriate onward referrals through the adoption of the stepped-care model. An additional advantage of implementing the screening programme was the formal identification of unmet patient need and that, in turn, supported the business case for a clinical psychologist post dedicated to medical dermatology. Reflections for nursing Nursing involvement with the stepped-care model outlined above is crucial. Indeed, nurses are well placed to address the psychological needs of patients with psoriasis, although this is sometimes not fully addressed in consultations. It was believed by our team that exploration of Dermatological Nursing, 2015, Vol 14, No 2 adjustment difficulties such as anxiety and depression (including suicidal thoughts), as well as patients’ methods of coping, would require training and the addition of a healthcare professional specialising in this work. The addition of a psychologist to our team has allowed ongoing training and support with the interpretation of screening tools and the development of care pathways from our psoriasis clinic. These changes have enabled the nursing team to truly offer holistic care for their patients. Recommendations for dermatology services Based on the work completed by our service so far we would encourage other dermatology departments to scope their unmet need for psychological support with service evaluation work, adapt a steppedcare model, and build psychological resources according to their setting. The development of nursing skills at steps 1 and 2 (NICE, 2009) is particularly important given the finite resource of team psychology. That is, such nursing skills allow a team psychologist more time to create selfhelp resources and focus on working at step 3 in individual or group therapy. It is noteworthy, however, that what is deemed sufficient as a method of self-help guidance is still not yet known. It is nonetheless encouraging that there has been some recent academic interest in this for people with physical health problems (Matcham et al, 2014) and, more specifically, in distress associated with skin conditions (Thompson, 2014a). Our self-help so far has been delivered as stand-alone or ‘pure self-help’ with little or no ongoing support from a clinician. Self-help supported by guidance from a clinician, where possible, may be a more effective option (Thompson, 2014a), although this might not necessarily be the case (Matcham et al, 2014). Further research is needed to look at the relative effectiveness of different methods of self-help for people with dermatological conditions such as psoriasis. www.bdng.org.uk Practice DEVELOPMENT www.bdng.org.uk Dermatological Nursing, 2015, Vol 14, No 2 29 Practice DEVELOPMENT We would emphasise that the use of IAPT is not a substitute for building internal resources, as this would not fully answer the service problem of requiring psychological support within dermatology. Moreover, without such integration, the mind-body link and message of de-stigmatisation is not fully made for patients with psoriasis. Nonetheless, we also acknowledge the usefulness of primary care psychology services, particularly where patients are less complex. Monitoring the extent to which dermatology patients access IAPT, either by GP or self-referral, is also important. More guidance on offering psychological support to dermatology patients is available from Thompson (2014b). Summary The present article has highlighted research and policy pointing to a need for changes in the landscape of health care for people with psoriasis, bringing together its physical and psychosocial aspects. We propose that our flexible stepped-care service model is allowing us to start addressing this need by drawing from existing resources in primary care and psychiatry while, in parallel, developing additional support within the dermatology department. DN References Al-Abadie MS, Kent GG, Gawkrodger DJ (1994) The relationship between stress and the onset and exacerbation of psoriasis and other skin conditions. Br J Dermatol 130(2): 199-203 Bewley A, Affleck A, Bundy C, Higgins E, McBride S, Millard L, Taylor R (2012) Working party report on minimum standards for psycho-dermatology services. British Association of Dermatologists, London Bundy C, Pinder B, Bucci S, Reeves D, Griffiths CEM, Tarrier N (2013) A novel, web-based, psychological intervention for people with psoriasis: the electronic Targeted Intervention for Psoriasis (eTIPs) study. Br J Dermatol 169(2): 329-336. a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Invest Dermatol 134: 1542-1551 Excellence, London. Available at: www. nice.org.uk/guidance/cg91 De Korte J, Sprangers MAG, Mombers FMC, Bos JD (2004) Quality of life in patients with psoriasis: a systematic literature review. J Invest Dermatol Symp Proc 9(2): 140-147 NICE (2011) Common mental health disorders: identification and pathways to care (Clinical guideline 123). National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, London. Available at: www.nice.org.uk/ guidance/cg123 Finlay AY, Khan GK (1994) Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) — a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol 19(3): 210-216 Fordham B, Griffiths CEM, Bundy C (2014) A pilot study examining mindfulness-based cognitive therapy in psoriasis. Psychol Health Med 20(1): 121-127 Fortune DG, Richards HL, Kirby B, et al (2003) Psychological distress impairs clearance of psoriasis in patients treated with photochemotherapy. Arch Dermatol 139(6): 752-756 Fortune DG, Richards HL, Kirby B, Bowcock S, Main CJ, Griffiths CEM (2002) A cognitive-behavioural symptom management programme as an adjunct in psoriasis therapy. Br J Dermatol 146(3): 458-465 Fortune DG, Richards HL, Kirby B, McElhone K, Main CJ, Griffiths CEM (2004) Successful treatment of psoriasis improves psoriasis-specific but not more general aspects of patients’ well-being. Br J Dermatol 151: 1219-1226 Kabat-Zinn J, Wheeler E, Light T, Skillings A, Scharf MJ, Cropley TG, Hosmer D, Bernhard JD (1998) Influence of a mindfulness meditation-based stress reduction intervention on rates of skin clearing in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis undergoing phototherapy (UVB) and photochemotherapy (PUVA). Psychosom Med 60(5): 625-632 Kimball AB, Jacobson C, Weiss S, Vreeland MG, Wu Y (2005) The psychosocial burden of psoriasis. Am J Clin Dermatol 6(6): 383-392 Kroenke K, Spitzer, RL, Williams JBW (2001) The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 16(9): 606-613 Matcham F, Rayner L, Hutton J, Monk A, Steel C, Hotopf M (2014) Self-help interventions for symptoms of depression, anxiety, and psychological distress in patients with physical illnesses: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev 34(2): 141-157 Christophers E (2007) Comorbidities in psoriasis. Clin Dermatol 25(6): 529-534 Menter A, Smith C, Barker J (2008) Psoriasis: Fast Facts, 3rd edn. Health Press Limited, Oxford Dowlatshahi EA, Wakkee M, Arends LR, Nijsten T (2014) The prevalence and odds of depressive symptoms and clinical depression in psoriasis patients: NICE (2009) Depression in adults with a chronic physical health problem: Treatment and management (Clinical guideline 93). National Institute for Health and Care 30 Dermatological Nursing, 2015, Vol 14, No 2 NICE (2012) Psoriasis: the assessment and management of psoriasis (Clinical guideline 153). National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, London. Available at: www. nice.org.uk/guidance/cg153 NICE (2013) QS40 — Psoriasis. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, London. Available at: www.nice.org.uk/ guidance/QS40 Rapp SR, Exum ML, Reboussin DM, Feldman SR, Fleischer A, Clark A (1997) The physical, psychological and social impact of psoriasis. J Health Psychol 2(4): 525-537 Richards HL, Fortune DG, Griffiths CEM, Main CJ (2001) The contribution of perceptions of stigmatisation to disability in patients with psoriasis. J Psychosom Res 50(1): 11-15 Richards HL, Fortune DG, Weidmann A, Sweeney SKT, Griffiths CEM (2004) Detection of psychological distress in patients with psoriasis: low consensus between dermatologist and patient. Br J Dermatol 151(6): 1227-1233 Sampogna F, Sera F, Abeni D (2004) Measures of clinical severity, quality of life, and psychological distress in patients with psoriasis: a cluster analysis. J Invest Dermatol 122: 602-607 Schmid-Ott G, Jaeger B, Boehm T, Langer K, Stephan M, Raap U, Werfel T (2009) Immunological effects of stress in psoriasis. Br J Dermatol 160(4): 782-785 Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW (1999) Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. JAMA 282(18): 1737-1744 Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JW, Löwe B (2006) A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The HSF-7. Arch Intern Med 166(10): 1092-1097 Thompson A (2009) Psychological impact of skin conditions. Dermatol Nurs 8(1): 43-48 Thompson AR (2014a) Self-help for management of distress associated with skin conditions. In: Bewley A, Taylor, RE, Reichenberg, JS, Magid, M (Eds) Practical Psychodermatology, pp60-66. Wiley, London Thompson AR (2014b) Treatment challenges: Getting psychodermatology into the clinic. Dermatol Nurs 13(4): 26-31 www.bdng.org.uk