* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Management of paediatric IBD

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

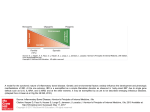

Milk intolerance in infants Food intolerance or food allergy ? Intolerance is not immune mediated For cow’s milk = lactose intolerant Lactose intolerance in infants = enteropathy Allergy is immune mediated IgE-mediated - local or systemic Non-IgE-mediated - local or systemic Lactose intolerance Normal in most adults in the world Tolerance mutation arose since dairy farming North Europeans usually tolerant as adults Lactase downregulated in teens Always abnormal in infants Very rare - congenital absence (Lapps) Very common - enteropathy Temporary – following rotavirus etc Persistent – with mucosal allergic sensitisation Eczema, GI symptoms Respiratory GI symptoms Urticaria, anaphylaxis T cells Eosinophils Mast cells David Hill et al Types of milk allergy IgE-mediated – rapid onset Systemic – anaphylaxis response Localised to gut – secretion, dysmotility Non-IgE-mediated – slow onset Systemic – Eczema, asthma Localised to gut – Enteropathy, colitis, eosinophilic GI disorders Mixed IgE and Non-IgE-mediated Detection of IgE-mediated food allergy usually straightforward Usually rapid onset of symptoms Symptoms are visible and easily related to food Usually supportive diagnostic tests Skin prick tests, specific IgE often positive Open food challenge easy to interpret Difficulties mainly occur if complex mixture of food antigens ingested Contrasting difficulty in non IgE-mediated food allergy N =14 Often delayed onset symptoms True association missed N=4 Symptoms often chronic Eczema, loose stools, ± poor weight gain Motility disturbance - colic, reflux, constipation Tests often negative Skin prick tests, specific IgE Skin patch tests – variable reports Hill et al, J Pediatr 1999 Cow’s milk sensitive enteropathy T cells become milk-sensitised Causes villous shortening, crypt lengthening Variable antibody response Epithelial function impaired Lactose malabsorbed Protein, fat malabsorption less striking Barrier function ↓ - 2o sensitisations Reflux or milk allergy? The screaming back-arching baby almost always is milk allergic – not simple GOR Even more likely if the baby has: Eczema, cradle-cap Colic Red swollen anus Nappy rash Candida Prolonged viral infections FH of atopy, autoimmunity (ask about thyroid disease) Causes of milk allergy Impaired oral tolerance mechanisms Loss of previously acquired tolerance Often pathogens break epithelial barrier eg Cow’s milk allergy after rotavirus Secondary sensitisation to soya etc Failure to establish oral tolerance initially Immunological abnormalities Inadequate innate immune exposures eg breast-milk sensitisation, multiple food allergy Oral tolerance Dependent on the gut flora Innate immune responses to flora are critical Mediated by regulatory T cells (TREG) Different mechanisms for low and high doses High doses – induce anergy of T cells Antigen presented by the epithelium Low doses – require active TREG generation Antigen taken up in lymphoid follicles Diagnosis of CMSE Depends on clinical recognition Skin prick test -ve Specific IgE -ve Features include: Post prandial distension, acid stools Weight gain often impaired May have eczema, colic, dermatographia Micronutrient deficiencies Coeliac diseasE Sir Samuel Gee The first modern description of coeliac disease 'chronic indigestion met with in persons of all ages, Yet especially apt to affect children between 1 and 5 years old‘ Lecture at GOS, 5th October, 1887 Hongerwinter – the Dutch famine 1944-5 Dicke WK (1950) Coeliakie. MD Thesis, Utrecht. Diagnostic aids Antibodies Anti-gliadin – moderate sensitivity- not specific Anti-reticulin – possibly more specific Anti-endomyseal/ TTG – sensitive and specific HLA association B8 – first described DR3 or DR5/7 - Much more predictive DQ2/DQ8 – actual association Coeliac disease Farrell and Kelly, NEJM 2002 Limitations of biopsy Changes may be non-specific. Similar appearances in other diseases Lesion may be patchy Capsule biopsies are jejunal, endoscopic are not Possibly less marked in D2 and D3 May even be absent in D2/3. IBD in childhood Rising incidence and change in phenotype Advances in genetics Immunological basis Inflammation required to establish tolerance The central role of the gut flora Pointers from epidemiology IBD and the “Clean-Child” hypothesis Dalziel’s report BMJ 1913 Autopsies on 13 patients with intestinal obstruction Inflamed jejunum, ileum or colon in all Transmural inflammation seen on histology “Crohn’s disease” Weiner 1914, Moschowitz & Wilensky 1923, 1927, Goldfarb & Suissman 1931 Ginzburg & Oppenheimer (for Berg) 1927,1928 Ginzburg & Oppenheimer with Crohn. May 2, 1932, AGA Crohn. May 13 1932, AMA Crohn BB, Ginzburg L, Oppenheimer GD. Regional ileitis: A pathologic and clinical entity. J Am Med Assoc 1932; 99: 1323 – 1328. Crohn’s or UC Crohn’s – Transmural. Focal chronic inflammation. Fibrosis. Granulomas. Anywhere along GI tract. Th1 response. UC – Largely mucosal. Diffuse acute and chronic inflammation. Essentially confined to colon. Indeterminate colitis. Definite IBD. Features between UC and Crohn’s. May evolve with time. IBD incidence Highest Scandinavia, Scotland Increased incidence on migration from low to high-risk countries Indian subcontinent origin in UK Ethnic groups Ashkenazi Jews IBD susceptibility genes European twin-birth registries Concordance for CD: MZ 37%, DZ 7% Concordance for UC: MZ 10%, DZ 3% Susceptibility loci from genome-scanning IBD1 – chromosome 16. CD. NOD2 gene IBD2 – chromosome 12q. UC > CD IBD3 - chromosome 6p. MHC locus IBD4 – chromosome 14q. CD IBD – breakdown of tolerance to the normal gut flora Enteric bacteria provide continuous immune challenge Evidence of specific unreactivity to own flora This is lost in active IBD Flora reactive T cells, antibody Reaction to normal flora causes experimental IBD Paediatric inflammatory bowel disease Similarities to adult IBD Essential inflammatory processes Mucosal lesion Differences to adult IBD Management emphasis Growth, puberty, psychosocial Indications for steroids, surgery Patterns of Paediatric IBD “Classical” Crohn’s disease and UC CD now becoming more prevalent Marked increase in incidence Ileocaecal involvement most common in CD Oral (/anal) Crohn’s Indeterminate colitis Aims of management Minimise impact of disease on: Linear growth Psychosocial development Pubertal development The family ie Multidisciplinary specialised therapy Diagnosis Clinical assessment exclude infectious aetiologies Upper endoscopy Colonoscopy (incl. ileoscopy) +/- Barium follow-through/ MR enteroclysis Mucosal healing Minimal Steroids, Mesalazine, Antibiotics Slow but definite healing Enteral nutrition, Azathioprine, 6MP Rapid but definite healing Infliximab, adlimumab Mucosal healing in Crohn’s disease Mucosal healing in UC Mucosal healing Only 29% of patients with colonic Crohn’s disease heal with corticosteroids Role of enteral nutrition Healing with azathioprine 70% heal with Infliximab single infusion improved histology / mucosal inflammation Current success... Induction of remission 75-85% within 2-4 weeks Maintenance of remission 60-70% relapse at 12 months 30% steroid dependent but..40-70% in remission on Aza at 12 months IBD Therapies Aminosalicylates Nutrition Antibiotics Corticosteroids Immunosuppressants Immunologic Surgery Steroid therapy Avoid when possible in children Poor effect on mucosa Second line agent relapsing disease severe exacerbation (i.v. hydrocortisone) Reducing course 2mg/kg (max 60mg / day) Enteral nutrition in paediatric IBD Highly effective first-line therapy Polymeric formulas more palatable Reduce pro-inflammatory cytokines Increase regulatory cytokines Animal models suggest alteration of gut flora Motivation of child and family critical Infliximab safety Short-term infusion related Medium term infectious complications delayed hypersensitivity antibody formation Long-term Malignancy – Hepato-splenic T cell lymphoma