* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Near-fatal outcome after administration of hyoscine-N-butylbromide (Buscopan )

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

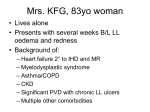

Case Studies: Near-fatal outcome after administration of hyoscine-N-butylbromide (Buscopan®) Near-fatal outcome after administration of hyoscine-N-butylbromide (Buscopan®) Milner A, MBBCh, FFA(SA), MPharmMed, FRCP(C), PGPCCE(Melb) Department of Anaesthesia, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa Correspondence to: Professor Analee Milner, e-mail address: [email protected] Keywords: anaphylaxis; angioneurotic oedema; hyoscine-N-butylbromide; porphyria Abstract While undergoing conscious sedation for a gastroscopy, an 18-year-old female developed severe hypotension and loss of consciousness. This occurred shortly after an intravenous dose of hyoscine-N-butylbromide (Buscopan®). Resuscitation was performed over a period of 10 minutes and was successful. Once conscious, the patient complained of severe lower abdominal pain. Except for a significant metabolic acidosis (BE = -10), initial investigations were negative. She was transferred to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) where the abdominal pain continued and the urine output was scanty for the first 12 hours. Investigations were done to exclude: anaphylaxis, mesenteric ischaemia, angioneurotic oedema, pregnancy, porphyria, autoimmune disease and myocardial ischaemia. Finally it was postulated that the drug had either caused an anaphylactoid reaction or grossly augmented cardiovagal nervous inhibition. This resulted in hypotension which caused mesenteric ischaemia that in turn resulted in severe abdominal pain and a degree of renal shutdown. S Afr J Anaesthesiol Analg 2010;16(4):38-41 Introduction Quaternary ammonium anticholinergic agents usually have some ganglion-blocking activity so that high doses may cause postural hypotension, but in toxic doses non-depolarising neuromuscular blockade and complete respiratory and cardiovascular collapse may be produced.1 Side effects may be increased with the simultaneous administration of other anticholinergic agents and other centrally acting drugs. There have been many reports of adverse reactions to hyoscine-N-butylbromide.1-5 This case is of special interest due to the complicated differential diagnosis. Hyoscine-N-butylbromide is frequently used for gastrointestinal spasm. It is a quaternary ammonium anticholinergic agent, acting primarily on parasympathetic ganglia in the walls of the viscera.1 Here it exerts a specific antispasmodic action on smooth muscle in the gastrointestinal, biliary and urinary tracts. Case report An eighteen-year-old female presented for gastroscopy. She gave no history of allergies or previous anaesthetic problems. She had received 20 mg hyoscine-N-butylbromide (Buscopan®) IV for abdominal cramps and Depo Provera IM for contraception two weeks prior to this procedure. Being an anticholinergic agent, all side effects and precautions cited for atropine should be applicable. Patients with glaucoma, urinary or gastrointestinal tract obstruction, unstable cardiovascular status and reflux oesophagitis should not be given this drug. This drug should be used with caution in patients with impaired metabolic, kidney and liver abnormalities. Her vital signs were normal; blood pressure was 100/60 mmHg and pulse 85 beats/minute. Apart from appearing extremely anxious, nothing abnormal was detected. Informed consent was obtained for conscious sedation. Futhermore, side effects such as dry mouth, tachycardia, blurred vision, confusion and cognitive impairment may be a problem. Hypersensitivity reactions, particularly skin reactions, have been described. S Afr J Anaesthesiol Analg Monitoring was instituted according to the recommendations of the South African Medical 38 2010;16(4) Case Studies: Near-fatal outcome after administration of hyoscine-N-butylbromide (Buscopan®) Association.6 A pulse oximeter and a non-invasive blood pressure device (NIBP) were connected. Oxygen was given via nasal cannulae. A 22G intravenous cannula was inserted into the dorsum of her right hand and an infusion of Lactated Ringers was initiated. The sedation consisted of: sufentanil 10 μg, midazolam 2 mg and, when the gastroenterologist was about to insert the gastroscope, 40 mg propofol was added. The patient complained of severe cramp-like lower abdominal and pelvic pain. She continued to receive 100% oxygen by mask. An additional infusion of hetastarch was initiated. Gradually her vital signs stablised as the blood pressure rose above 100 mmHg systolic and the pulse dropped below 95 beats/minute. While still on the operating table the following tests were done: 1. A 12-lead ECG, that showed a sinus tachycardia, but no ischaemia. 2. An arterial blood gas that showed a severe metabolic acidosis with pH = 7.31, BE = -10 and HCO3- = 18. 3. A cardiologist examined her heart and a transthoracic echocardiograph was done while the patient was still on the operating table. Her heart appeared normal. 4. A radiologist did an ultrasound of her uterus and ovaries, which also appeared normal. Her blood pressure dropped to 85/55 mmHg and her pulse rate slowly drifted down to 48/minute and then 44/minute. The oxygen saturation (SaO2) remained at 100% throughout. The slowing of the pulse rate did not cause concern as she was young, it was a “sleeping pulse”, and she had received an opioid and propofol. Approximately four minutes after the start of the gastroscopy, 20 mg of hyoscine-N-butylbromide was given intravenously. At this point the pulse was 42/minute, the SaO2 saturation 100% and the blood pressure 85/55 mmHg. She was then transferred to the ICU and monitored for the next 24 hours. She continued to complain of severe lower abdominal pain. No bowel sounds were present, but her abdomen was soft. A general surgeon was consulted to rule out the possibility of mesenteric ischaemia. When she began menstruating a gynaecologist was consulted and the β-HCG to rule out an aborting pregnancy was negative. Her urine output was relatively scanty as she passed approximately 400 ml over an eight hour period. She also complained of chest pain and this was thought to be due to the cardiac massage. A tachycardia of 140 beats/min occurred almost immediately. The gastroenterologist commented that the gastric mucosa appeared mottled with areas of extreme blanching, indicative of severe vasoconstriction. The patient began to cough and groan. A further 20 mg propofol was given, but did not appear to sedate her. The heart rate went up to 150/ minute and the NIBP monitor was “unable to record”. No peripheral pulses were present, but a weak central pulse was palpable. The gastroscope was removed, the patient turned on to her back and an ECG monitor was immediately connected. At this point she was still breathing spontaneously, but the oximeter probe was no longer registering. The operating table was placed in Trendellenburg and the infusion of Lactated Ringer’s was increased to facilitate a faster flow. Cardiac massage was initiated and adrenaline was titrated in 100 μg increments. The first recordable blood pressure of 40 mmHg systolic was then measured with a manual sphygmonometer. Her arterial blood gases gradually normalised. Twentyfour hours post cardiac arrest, a significant diuresis occurred. She passed 1 500 ml urine over a two hour period. She was discharged from ICU later that day. The following blood tests were done in an attempt to determine the exact cause of the cardiovascular collapse: a. Anaphylaxis: serum tryptase specific IgE antibodies3 b. Angioneurotic oedema: C1-INH c. Pregnancy: β-HCG d. Autoimmune disease: antinuclear factor e. Myocardial ischaemia: cardiac enzymes. At this point the respiration was erratic and manual ventilation with 100% oxygen was intiated, followed by tracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation. The next blood pressure recorded by the NIBP was 60 mmHg systolic. A further 500 μg of adrenaline was titrated over 60 seconds. Her blood pressure rose to 85/50 mmHg and her pulse came down to 135/minute. She regained consciousness and pulled out her endotracheal tube. The time from administration of the drug to her extubation was nine and a half minutes. S Afr J Anaesthesiol Analg Urine was also tested, for porphyrins and urinary methyl histamine to exclude porphyria and anaphylaxis. Discussion Hyoscine-N-butyl bromide is known to cause adverse cardiovascular side effects.2,3,4,7 Anaphylaxis and 39 2010;16(4) Case Studies: Near-fatal outcome after administration of hyoscine-N-butylbromide (Buscopan®) angioneurotic oedema appear high on the list and needed to be excluded. Although bronchocutaneous manifestations need not be present for both these conditions, the absence of urticaria and bronchospasm should force the physician to include other pathologies in the differential diagnosis. d. A haemorrhage caused by an ectopic pregancy or incomplete abortion causing a haemodynamic collapse and lower abdominal pain. e. An anaphylactoid reaction, causing a “shock”-like picture. Scopolamine has been known to markedly and paradoxically augment cardiovagal nervous inhibition in healthy young subjects.7 in this study low dose scopolamine was postulated to decrease blood pressure by increasing sympathetic cholinergic outflow in the vessels of striated muscle. f. Angioneurotic oedema. This patient had abdominal pain, but no other oedema was evident. Hereditary angioneurotic oedema is an autosomal dominant state associated with the absence of functional C1-INH. The diagnosis suggested not only by family history but also by the lack of urticarial reactions and the predominant signs of gastro-intestinal attacks of colic, and episodes of laryngeal oedema.2 After the anti-muscurinic agent was administered, severe vasoconstriction of the gastric mucosa occurred, as seen by the intense blanching of the gastric mucosa. As acetyl choline normally causes vasodilatation,7 it is logical to assume that an antimuscurinic must cause some degree of vasoconstriction. In our patient the constriction must have been so severe that a degree of mesenteric ischaemia occurred and probably was the cause of her arousal prior to the gastroscope removal. Transthoracic echocardiography in this patient was normal, she had no apparent anatomical abnormality that would make her unable to tolerate a sinus tachycardia of 150 beats/min. Clinically she did not appear to be dehydrated and her reaction to the anaesthetic agents used for conscious sedation was not consistent with that of a dehydrated patient. Shortly after this the blood pressure then dropped to such an extent that she lost consciousness and renal shutdown resulted. A severe metabolic acidosis reflected this acute peripheral and central shutdown. An ultraound of her uterus and ovaries was negative; a negative β-HCG ruled out a possible complicating pregnancy. At the time of the haemodynamic collapse, the cause was not evident and the following aethiologies had to be excluded: a. b. c. In a few cases angioneurotic oedema has been reported as a side effect of this drug. Although this patient had severe abdominal pain, she had none of the other signs of this condition such as urticarial skin lesions and laryngeal oedema. Abnormal cardiac anatomy, such as a left ventricular outflow tract obstruction (HOCAM) or aortic stenosis. This would imply that the patient would be unable to maintain a cardiac output as the heart rate rose significantly after the antimuscurinic agent. It is known that young patients react with a greater degree of tachycardia to all antimuscurinic agents than older patients.6 By exclusion, an anaphylactiod reaction seems the most probable cause. However, she had none of the other clinical signs that usually accompany these reactions, such as bronchospasm, urticaria and weals. It is postulated that 25% of anaphylactoid/ anaphylactic reactions do not manifest these usual bronchocutaneous signs. Unfortunately not all of the blood tests to investigate anaphylaxis were done such as serum tryptase, urinary methyl histamine and specific IgE antibodies.3 Tachy-dysrhythmia caused a drop in cardiac output. She did not have continuous ECG monitoring at the time she received hyoscine. According to the South African Medical Association guidelines, a continuous ECG monitor is only necessary during conscious sedation if the patient has some cardiac problem.5 The patient was a young healthy adult. Conclusion Immediately after the administration of hyoscine N-butylbromide, this patient presented with cardiovascular collapse that caused a loss of consciousness that necessitated intubation and the use of 1 500 μg of adrenaline. She developed a metabolic acidosis, renal shutdown and probably Hypovolaemia due to the enforced period of starvation for eight hours prior to the gastroscope. At the time of the cardiovascular collapse she had received about 300 ml of Lactated Ringers. S Afr J Anaesthesiol Analg 40 2010;16(4) Case Studies: Near-fatal outcome after administration of hyoscine-N-butylbromide (Buscopan®) mesenteric ischaemia that persisted for eight hours post-operatively. 3. 4. Blood tests to confirm an anaphylactic reaction were not done, but by exclusion the most likely cause was an anaphylactoid reaction after the administration of hyoscine N-butylbromide. 5. 6. 7. Bibliography 1. 2. 8. MIMS Desk Reference Vol 34 1999. Buscupan ampoule 260–261. Thomas AMK, Kubie AM, Britt RP. Acute angioneurotic oedema following a barium meal. British Journal of Radiology. 1986;59:1055–1056, Harrison’s principles of Internal Medicine 9th edition. Mc Graw-Hill Book Company 343–345. Aether volume 1 issue 2. Allergy and anaesthesia. Laxemaire MC, et al. 14–18. Treweeke P, Barrett NK. Allergic reaction to Buscopan. A letter. BJRad. 1987;60:417–8. Thomas AMK, Kubie AM, Britt RP. Angioneurotic oedema following a barium meal. BJRad. 1986;59;1055–1056. Conscious Sedation Working Group, Medical Association of South Africa. Conscious sedation clinical guideline. SAMJ.April 1997;part 2:484–492 Vesalainen RK, Tahvanainen KUO, et al. Effects of low-dose transdermal scopolamine on autonomic cardiovascular control in healthy young subjects. Clinical physiology. 1997:17;135–148 Admin. S Afr J Anaesthesiol Analg 41 2010;16(4)