* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Status Epilepticus in CHildren

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

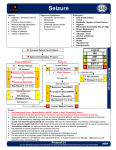

Status Epilepticus in Children Definitions • Status Epilepticus: 30 minute duration of seizures (or two or more sequential seizures without full recovery of consciousness between seizures). For practical purposes, start treatment earlier • Seizure: paroxysmal event characterized by a change in behavior of the patient; it is caused by abnormal and excessive activity of a group of cortical neurons. • Epilepsy: occurrence of two or more unprovoked seizures Status epilepticus • Common in children, particularly in children less than 2 years old • Particularly common in children with epilepsy (9-27% over time have at least one episode of status) • High morbidity and mortality Complications • • • • • • Hypoxemia Acidemia Glucose alterations Blood pressure disturbances Increased intracranial pressure Morbidity – Neurologic sequelae – – – – – • Mortality – 3-4% Focal motor deficits Mental retardation Behavioral disorders Chronic epilepsy Acute and chronic MRI changes Assessment of the Patient with Status Epilpeticus 1. 2. 3. 4. Determine if patient is having a seizure Determine type of seizure Determine possible etiology of seizure Treat underlying etiology of seizure if pertinent 5. Stop the seizure Differential Diagnosis Is patient having a seizure?? • Movement Disorder – Drug induced dystonic reaction – Paroxysmal dyskinesias – Sandifers syndrome • Breathholding spell • Syncope • Spasm – Secondary to increased ICP • Psychogenic seizure • Narcolepsy (cataplexy) Classification of seizures Generalized Partial • loss of consciousness • whole brain at onset • no loss of consciousness • focal onset Convulsive Complex Partial • tonic clonic • tonic • clonic • change in level of consciousness Nonconvulsive • • • • absence atypical absence myoclonic atonic Simple Partial • no change in consciousness Partial Seizure evolving to secondary generalization Etiology of Status Epilepticus • • • • • Acute symptomatic Remote symptomatic Progressive encephalopathy Febrile Cryptogenic/Idiopathic Acute Symptomatic Seizures • Fever • Infectious – Meningitis – Abscess – Encephalitis • Neurovascular – Ischemic stroke – Hemorrhagic stroke (AVM, aneurysm, etc) • Trauma • Tumor • Metabolic – Hypoglycemia – Hypocalcemia – Hyponatremia Management of Status Epilepticus in Children--Initial Approach Status Epilepticus Working Party, 2000 (mostly) • Initial assessment – – – – A, B, Cs Rapid neurologic examination Brief history Give high flow oxygen • Measure rapid blood glucose – More to avoid glucose infusion than the uncommon hypoglycemic seizures • Confirm epileptic seizure – Not all events are epileptic!!!! • Laboratory Studies – – – – – Glucose, electrolytes, calcium, magnesium ABG CBC Serum anticonvulsant drug levels (if indicated) Toxicology screening Rapid Neurologic Evaluation • Observation – What is the patient doing • • • • What are the movements? Which extremities involved? Stiff or floppy? What are eyes doing? Head? Is patient at all responsive? • Mental Status – Can you get the patient to respond? Verbal? Noxious stimuli (not too noxious!)? Appropriate withdrawal? • Cranial Nerves – Pupil reactivity, extraocular movements • Motor/Sensory: – What parts of body are moving? What parts withdraw to nailbed pressure Brief history • • • • Has the child ever had a seizure before? History of trauma? Fever? Ingestion? Was the child his usual self prior to this event? What medications (including nonprescription) does the child take? • Any medical problems? • Any neurologic/developmental problems? • If child has known epilepsy – Name and dosage of medications!!! Calculate if this is appropriate dosage. – Has the child missed dosage of medication • If so, consider loading with that medication – Be aware of paradoxical side effects of ACDS • Phenytoin and carbamazepine toxicity may precipitate SE Management of Status Epilepticus in Children--Initial Approach • Initial assessment – – – – A, B, Cs Rapid neurologic examination Brief history Give high flow oxygen • Measure rapid blood glucose – More to avoid glucose infusion than the uncommon hypoglycemic seizures • Confirm epileptic seizure – Not all events are epileptic!!!! • Laboratory Studies – – – – – Glucose, electrolytes, calcium, magnesium ABG CBC Serum anticonvulsant drug levels (if indicated) Toxicology screening No Caption Found The Status Epilepticus Working Party, et al. Arch Dis Child 2000;83:415-419 Management of Status Epilepticus in Children 1. Stop the seizure 2. Keep seizure from recurring Treatment of Status Epilepticus: 1. STOP the seizure with benzodiazepine – If no IV access: Diazepam 0.5 mg/kg PR • Diastat • IV diazepam, inserted per rectum through butterfly (needle cut off!) – If IV access: Lorazepam • 0.1 mg/kg IV over 30-60 seconds • If seizures continue another 10 minutes, repeat lorazepam – Midazolam: IV, buccal, nasal 2. ADD fosphenytoin (either as second medication if seizure refractory, or to stop from recurring) – 20 PE/kg IV 3. ADD third medication if necessary- Phenobarbital, Valproic acid, Keppra Benzodiazepines • Diazepam vs. Lorazepam • Diazepam – Highly effective in rapidly terminating seizures – However, redistribution into adipose tissue limits anticonvulsant effect to less than 20 minutes – Available in rectal gel, which can be given outside the ED • Lorazepam – – – – Equally or more effective than diazepam Longer duration of action (6-12 hours vs. <1 hour) Less respiratory depression than diazepam Not available rectally Treatment of Status Epilepticus in the Child Step 2 • ADD fosphenytoin:20 PE/kg over 7 min. – If fosphenytoin not available, use phenytoin: 18-20mg/kg over 20 minutes – General rule of thumb: for each 1 mg/kg phenytoin (or 1PE/kg fosphenytoin) expect level to rise by 1) • If already on phenytoin, load with phenobarbital 20mg/kg over 10 minutes Phenytoin vs. Fosphenytoin • • • • • • Phenytoin Can be diluted in NS only! Maximum concentration of 10mg per ml Infusion rate < 1 mg/kg/min (Therefore 18 mg/kg is infused over no less than 18 minutes) Risk of hypotension and cardiac arrythmia Monitor heartrate BP and EKG Extravasation reaction, purple glove syndrome • • • • • • Fosphenytoin Pro drug: converted into phenytoin Can be diluted in commonly used diluents Can infuse 3 times more rapidly than phenytoin (ie, over 7-8 minutes) Decreased risk hypertension and arrhythmia Decreased risk extravasation reactions (pH of 8) Dosed in phenytoin equivalents (PE) which can be confusing. Treatment of Status Epilepticus in the Child Step 3 • ADD third medication if necessary – Phenobarbital 20mg/kg IV (2 mg/kg/min)\ • • may repeat 10mg/kg every thirty minutes Be prepared to intubate as barbituates and benzos potentiate each others effects – Valproic Acid • Not yet approved for initial treatment of SE • Dosage 20-40 mg/kg IV (diluted 1:1 with normal saline or 5% dextrose in water) over 5-10 minutes; may repeat in 10-15 minutes; follow with IV infusion of 5 mg/kg/hr – Keppra • Not approved for initial treatment of SE Refractory Status Epilepticus • Definition: continued seizures after 2 or 3 antiepileptic drugs have failed • Will usually need EEG monitoring at this point; typically titrate to burst suppression Managementof Refractory Status Epilepticus in the Child • Confirm this is truly an epileptic seizure and continue to look for underlying treatable cause • Call for back up from anesthetist or intensive care specialist Treatment of Refractory Status Epilepticus in the Child • • Inhalational anesthetics Pentobarbital • Propofol • Midazolam • Valproic acid • • Keppra Consider IV pyridoxine • Short acting; Significant side effects: respiratory depression, hypotension, myocardial depression, reduced cardiac output, pulmonary edema, ileus; Intubation and intravascualr monitoring usually required • Thiopental • Active metabolites which can accumulate; Possibly higher adverse reactions than pentobarbital • Intravenous anesthetic; Risk of hypotension, apnea and bradycardia • Contraindicated in child on ketogenic diet • Short half life; IV, IM, intranasal, PO, buccal or rectal • 0.1-0.3 mg/kg IV followed by 1mcg/kg/min IV infusion; increase every 15 minutes as necessary; maximum 8-10 mcg/kg/min • 20-40 mg/kg IV (diluted 1:1with normal saline or 5% dextrose in water) over 5-10 minutes; may repeat in 10-15 minutes. Follow with IV infusion of 5 mg/kg/hr Valproic acid • Not yet approved for initial treatment of SE • Appears effective and safe • Dosage – 20-40 mg/kg IV (diluted 1:1 with normal saline or 5% dextrose in water) over 5-10 minutes; may repeat in 10-15 minutes – Follow with IV infusion of 5 mg/kg/hr Propofol – Intravenous anesthetic – Small number of studies show effectiveness – Risk of hypotension, apnea and bradycardia – Contraindicated in child on ketogenic diet Midazolam – Short half life – IV, IM, intranasal, PO, buccal or rectal – Can be given as continuous IV infusion for refractory SE – Midazolam infusion • 0.1-0.3 mg/kg IV followed by 1mcg/kg/min IV infusion. • Increase every 15 minutes as necessary • Maximum 8-10 mcg/kg/min Pentobarbital • Short acting; used for refractory SE • Significant side effects: respiratory depression, hypotension, myocardial depression, reduced cardiac output, pulmonary edema, ileus • Intubation and intravascualr monitoring usually required • Thiopental – Used for refractory SE – Active metabolites which can accumulate – Possibly higher adverse reactions than pentobarbital Diagnostic assessment Riveillo et al: Practice Parameter: Diagnostic assessment of the child with status epilepticus (an evidence-based review) Neurology 2006;67:1542-1550 • CBC, electrolytes, calcium, glucose • Anticonvulsant levels (if applicable) • LP: only if there is clinical suspicion of meningitis – If this is first febrile seizure, presenting as status, LP will usually need to be performed • Consider toxicology testing • Metabolic and genetic testing: only if specific concern at first seizure (eg: history of recurrent lethargy, etc) • Consider neuroimaging: – MRI better sensitivity, but may not be available – CT better for evaluation of acute blood, skull fractures • Obtain EEG (not in acute period) Disposition • Patient gets admitted for observation for 24 hours Home treatments for Status Epilepticus • Diastat – Dosage: 0.5 mg/kg, round up – DIASTAT AcuDial • 10mg delivery system with a 4.4 cm tip (delivers doses of 5, 7.5 and 10 mg) • 20 mg delivery system with a 6.0 cm tip (delivers doses of 10, 12.5 and 20 mg) • Twin Pack of 2 pre-filled configurations (pharmacist locks in proper dosage) • Intranasal midazolam Neonatal Seizures Neonatal Status Epilepticus Etiology • • • • • • • Hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy CNS infection Intracranial Hemorrhage Cerebral Infarction Chromosomal abnormalities Congenital Brain abnormalities Metabolic Distubances – – – – Hypoglycemia Hypocalcemia Hypomagnesemia Pyridoxine dependency • Inborn errors of metabolism • Drug withdrawal or intoxication Neonatal Seizures Etiology Time of Onset Hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy 12-24 hour Drug withdrawal 24-72 hour Hypocalcemia (nutritional) 3-7 days Aminoaciduria/organic aciduria 3-7 days Differential Diagnosis of Neonatal Seizures by Peak Time of Onset Fenichel, 2nd ed. • 24 hours • 72 hours – 1 week 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. Meningitis/Sepsis Direct drug effect Hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy Intrauterine infection Laceration of tentorium or falx Pyridoxine dependency Subarachnoid hemorrhage • 24-72 hours 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. Familial neonatal seizures Cerebral dysgenesis Cerebral infarction Hypoparathyroidism Intracerebral hemorrhage Kernicterus Nutritional hypocalcemia Methylmalonic/ propionic acidemia Urea cycle abnormalities 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. Meningitis/sepsis Drug withdrawal Cerebral contusion/SDH Cerebral dysgenesis IVH in newborns Pyridoxine dependency Subarachnoid hemorrhage Urea cycle abnormalities Hypoparathyroidsm-hypocalcemia • 1 week- 4 weeks 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. Neonatal adrenoleukodystrophy Cerebral dysgenesis Fructose dysmetabolism Gaucher Type 2 Gm1 gangliosidosis Herpes simplex encephalitis MSUD Urea cycle abnormalities Diagnostic Assessment of Neonatal Seizures • Metabolic testing (screening) – – – – – – • LP – – – – – – • Blood glucose Calcium Ammonia Lactate pH electrolytes Cells Protein/glucose Cultures Herpes PCR Lactate/pyruvate Aminoacids Neuroimaging – – – Head ultrasound Head CT Brain MRI Neonatal Status Epilepticus Treatment • Etiology specific treatment if possible – Hypoglycemia • Correct with 10% glucose solution IV 2cc/kg • Maintenance glucose infusion to max of 8 mg/kg/min – Hypocalcemia • Treat with 10% calcium gluconate (100 mg/kg or 1ml/kg IV over 5-10 minutes while monitoring heart rate and infusion site; or calcium chloride (20mg/kg or 0.2 ml/kg) – Hypomagnesemia • Often associated with hypocalcemia • Treat with 50% solution of magnesium sulfate IM, 0.25 ml/kg – Pyridoxine dependency • Used empirically in infants with refractory seizures • While EEG monitoring, give 100 mg/kg IV Neonatal Status Epilepticus Treatment • Phenobarbital – Usually used first – Prolonged half life—100 hours after day 5-7; therefore watch for toxicity – 20 mg/kg IV (up to 40 mg); repeat 10/kg every 15-30 minutes times two • Phenytoin/Fosphenytoin – 20 mg/kg (over 30-45 minutes) – Half-life 100 hours – Nonlinear kinetics; redistribution, variable rate hepatic metabolism require individuallization of maintenance dosing • Benzodiazepine – Diazepam • 0.25mg/kg IV bolus or 0.5 mg/kg PR – Lorazepam • 0.05 mg/kg IV over2-5 minutes • Midazolam infusion References • • • • • • • Riviello JJ et al: Practice Parameter: Diagnostic assessment of the child with status epilepticus (an evidence based review): Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the Practice Committee of the Child Neurology Society, Neurology 2006;67;1542-1550. Appleton et al: Drug management for acute tonic-clonic convulsions including convulsive status epilepticus in children, The Cochrane Collaboration, Volume (4), 2006. Fenichel GM: Clinical Pediatric Neurology: A Signs and Symptoms Approach, 5th Edition, Elsevier Suanders 2005, p 1-45. Mizrahi,EM and Kellaway p: Diagnosis and Management of Neonatal Seizures, Lippincott-Raven, Philadelphia, 1998,p. 181. Tharp, Barry: Management of Status Epilepticus in Children, Uptodateonlline.com The Status Epilepticus Working Party: The treatment of convulsive status epilepticus on children, Arch Dis Child 2000;83;415-419. Wolfe et al: Intranasal midazolam therapy for pediatric status epilepticus, American Journal of Emergency Medicine 2006; 24(3);343-346.