* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Document

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

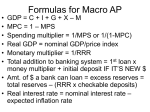

Principles of Economics Session 11 Topics To Be Covered Identities of Saving and Investment Consumption Function Marginal Propensity to Consume Marginal Propensity to Save Investment Function Equilibrium of the Goods Market Case Study: Output Accounting and Output Determination Topics To Be Covered Business Cycle Fiscal Policy Multiplier Effect Crowding-Out Effect Paradox of Thrift National Saving National saving is the amount of income that households have left after paying their taxes and consumption and the revenue that the government has left after paying for its purchases. National Saving = Private Saving + Public Saving Private Saving Private saving is the amount of income that households have left after paying their taxes and paying for their consumption. Private Saving = Y – T - C Public Saving Public saving is the amount of tax revenue that the government has left after paying for its spending. Public Saving = T - G Surplus and Deficit Budget Surplus If T>G, the government runs a budget surplus because it receives more money than it spends. Budget Deficit If G>T, the government runs a budget deficit because it spends more money than it receives in tax revenue. Identities of Saving and Investment Assume a economy consisting of households and firms only. The expenditures are consumption and investment and the incomes are either spent on consumption or saved. C+I=C+S Therefore, saving is equal to investment. I=S Identities of Saving and Investment In a closed economy with households, firms, and government, there exists the following equation, the left side being expenditures and the right side being income allocations: C+I+G=C+S+T Therefore, the national saving is equal to investment. I = S + (T – G) Identities of Saving and Investment In an open economy, import and export should be considered. Since the aggregate income (Y) is equal to the aggregate expenditure, there exist the following equations: Y= C + I + G + NX I + NX = Y – C - G Identities of Saving and Investment For an economy as a whole, net export (NX) and net foreign investment (NFI) must balance each other so that: NX = NFI Therefore, in an open economy national saving is equal to the sum of domestic investment and net foreign investment. I + NFI = (Y – C -T ) – (T – G) Consumption and Saving In a society without tax, a household can do two things with its income— consumption and saving. Y=C+S Determinants of Consumption Household income Household wealth Interest rates Households’ expectations Consumption Function Keynes points out that the household consumption is closely related to the income. With the income increase, people will consume more. However, the increase of consumption is not as great as that of income. Empirical studies also reveal the close relationship between consumption and income but the increase of consumption is on the whole proportional to income. Consumption Function Keynes’ View Consumption C=Y C = f ( Y) 45º Income Consumption Function Empirical Finding Consumption C=Y C = a + bY 45º Income Marginal Propensity to Consume The marginal propensity to consume (MPC) is the extra amount that people consume when they receive an extra dollar of income. Marginal Propensity to Consume Consumption MPC = f ‘( Y) C = f ( Y) MPC=Slope Income Marginal Propensity to Consume Consumption C = a + bY MPC=Slope=b Income Consumption Function Keeping other variables (interest rate, expectation, etc.) constant, consumption can be thought of as a function of income. C = f (Y) If the function is linear, it can be expressed as: C = a + bY Consumption Function Aggregate Income (Y) (Billion Dollars) 0 80 100 200 400 600 800 1,000 Aggregate Consumption (C) (Billion Dollars) 100 160 175 250 400 550 700 850 Consumption Function Consumption C = 100 + 0.75Y 100 Income Marginal Propensity to Save The marginal propensity to save (MPS) is the fraction of an additional dollar of income that is saved. MPC + MPS = 1 MPS = 1 - MPC Marginal Propensity to Save Aggregate Income 0 80 100 200 400 600 800 1,000 Aggregate Consumption Aggregate Saving (All in Billion Dollars) 100 160 175 250 400 550 700 850 -100 -80 -75 -50 0 50 100 150 Marginal Propensity to Save consumption C=Y C = 100 + 0.75Y 0 Save 45° Income MPS = 0.25 S = -100 + 0.25Y 0 Income Investment Investment refers to purchases by firms of new buildings and equipment and additions to inventories, all of which add to firms’ capital stocks. Generally, investment is considered a function of interest rate (r). When the interest rate is high (low), the financial cost for the firm is high (low), the firm invests less (more). Investment Interest rate I = f (r) Investment Planned Investment Desired or planned investment refers to the additions to capital stock and inventory that are planned by firms. Actual investment is the actual amount of investment that takes place; it includes items such as unplanned changes in inventories. Planned Investment For simplicity, it is assumed that planned investment is fixed, for the major determinant of investment is the interest rate and the investment is an exogenous variable in the Keynesian cross model. It does not change when income changes, so investment is an autonomous variable. Planned Investment Investment I = 25 Income Planned Aggregate Expenditure To determine planned aggregate expenditure (AE), we add consumption spending (C) to planned investment spending (I) at every level of income. Planned Aggregate Expenditure C+I AE = C+ I = 125 + 0.75Y C = 100 + 0.75Y 125 100 25 I = 25 Y Equilibrium in Goods Market In macroeconomics, equilibrium in the goods market is the point at which planned aggregate expenditure is equal to aggregate output. Y=C+I Equilibrium in Goods Market Y>C+I Inventory investment is greater than planned. Actual investment is greater than planned, so there is unplanned inventory Y<C+I Inventory investment is smaller than planned. There is negative unplanned inventory. Equilibrium in Goods Market Saving is a leakage out of the spending stream. If planned investment is exactly equal to saving, then planned aggregate expenditure is exactly equal to aggregate output, and there is equilibrium. Aggregate output will be equal to planned aggregate expenditure only when saving equals planned investment (S = I). Case Study: Output Accounting and Output Determination Assume an economy consists of the firm and the family only and the firm produces a single product—bread. Case Study: Output Accounting and Output Determination The firm thinks that the household will consume $800 of bread. Considering that the firm needs the inventory $200 of bread to entertain international guests, the firm produces $1000 worth of bread. Case Study: Output Accounting As expected, the firm sells exactly $800 of bread and keeps an inventory of $200 of bread. What’s the GDP of this economy for this period? Case Study: Output Accounting Aggregate Output=$1000 Aggregate Income=$1000 Output:$1000 Aggregate Expenditure=C+I=$1000 GDP=$1000 Consumption: $800 Income: $1000 Inventory: $200 Case Study: Output Determination As expected, the firm sells exactly $800 of bread and keeps an inventory of $200 of bread. Is the goods market in equilibrium? Why? Output = AS: $1000 Case Study: Output Determination Planned Expenditure = AD: $1000 Planned Saving: $200 Unplanned Inventory: $0 Income: $1000 Case Study:Output Determination AD= Planned Expenditure =C+I AS=AD Output=AD, so the C+I 1000 0 Investment here doesn’t include unplanned inventory, so investment does not necessarily equal saving. 45° 1000 Saving and Investment goods market is in equilibrium. GDP= AS =Output = Income=C+S Planned Saving Planned Investment 200 0 1000 GDP=Income Case Study: Output Accounting Unexpectedly, the firm sells only $600 of bread, so it has to keep an inventory of $400 of bread. What’s the GDP of this economy for this period? Case Study: Output Accounting Aggregate Output=$1000 Aggregate Income=$1000 Output:$1000 Aggregate Expenditure=C+I=$1000 GDP=$1000 Consumption: $600 Income: $1000 Inventory: $400 Case Study: Output Determination Unexpectedly, the firm sells only $600 of bread, so it has to keep an inventory of $400 of bread, $200 of which is unplanned inventory. Is the goods market in equilibrium? Why? Output = AS: $1000 Case Study: Output Determination Planned Expenditure = AD: $800 Planned Saving: $400 Unplanned Inventory: $200 Income: $1000 AD= Planned Expenditure =C+I Case Study:Output Determination Output is greater than AD by $200 800 0 C+I 45° Saving and Investment Equilibrium output 1000 GDP= AS =Output = Income=C+S S 400 I 200 0 1000 Other things held constant, the firm should decrease its output next period. Planned saving is greater than planned investment by $200. GDP=Income Case Study: Output Accounting Unexpectedly, the firm sells all the bread it has produced—$1000 of bread, so it has run out of inventory. What’s the GDP of this economy for this period? Case Study: Output Accounting Aggregate Output=$1000 Aggregate Income=$1000 Output:$1000 Aggregate Expenditure=C+I=$1000 GDP=$1000 Consumption: $1000 Income: $1000 Inventory: $0 Case Study: Output Determination Unexpectedly, the firm sells all the bread it has produced—$1000 of bread, so it has run out of inventory, which means a negative unplanned inventory of $200. Is the goods market in equilibrium? Why? Output = AS: $1000 Case Study: Output Determination Planned Expenditure = AD: $1200 Planned Saving: $0 Unplanned Inventory: - $200 Income: $1000 AD= Planned Expenditure =C+I Case Study:Output Determination C+I 1200 Output is smaller than AD by $200 0 45° 1000 Saving and Investment Other things held constant, the firm should increase its output next period. Equilibrium output GDP= AS =Output = Income=C+S S I 200 0 1000 Planned saving is smaller than planned investment by $200. GDP=Income Case Study: Output Determination Planned Planned Planned GDP Consumption Saving Investment 1000 600 400 200 1000 800 200 1000 1000 0 GDP Total Planned C and I Resulting Tendency of Output Contraction 200 1000 > 800 1000 = 1000 Equilibrium 200 1000 < 1200 Expansion Business Cycle GDP Peak Trend Growth Trough Trough Time Business Cycle AE AE 800 0 45° 150 GDP Equilibrium output 1000 Expansion Trough Peak Recession Business Cycle A recession is a period of declining real GDP, falling incomes, and rising unemployment. A depression is a severe recession. Business Cycle Economic fluctuations are irregular and unpredictable. Most macroeconomic variables fluctuate together. As output increases, unemployment falls, but the price level increases. Fiscal Policy The government can play a very important role in smoothing the economic fluctuation. When the economy is in recession, the government may adopt expansionary policy—decrease taxes or increase spending. When the economy develops too fast, the government may adopt contractionary policy—increase taxes or decrease spending. Expansionary Fiscal Policy AS Price Level P2 P1 AD2 AD1 0 Q1 Potential Output Quantity of Output Contractionary Fiscal Policy AS Price Level P1 P2 AD1 AD2 0 Potential Output Q1 Quantity of Output Potential Output The potential output is determined by the stock of labor, capital, land, and technology. The price level has little effect on the supply of these factors in the long run. So in the ASAD model, the potential output is vertical. This level of production is also referred to as natural rate of output or full-employment output. Fiscal Policy and Aggregate Expenditure In a closed economy with three sectors— firms, households, and government. Government spending (G) is a very important component in aggregate expenditure. AE = C + I + G In the Keynesian model, government spending does not change with output, so G is an autonomous variable. Fiscal Policy and Aggregate Expenditure AE 150 125 100 50 25 C+I+G = 150 + 0.75Y C+ I = 125 + 0.75Y C = 100 + 0.75Y G = 25 I = 25 Y The Multiplier The 1 dollar increase of autonomous variable (investment, government purchase, etc.) is likely to result in more than 1 dollar increase in total output. For example, if the government spending increases by $1, the individual who earns that dollar saves $0.25 and pays $0.75 for a book. △GDP = $1 + $0.75 = $1.75 The Multiplier If the book seller saves 25% of $0.75 received and spends 75%, the increase of GDP is: △GDP = $1 + $0.75 + $0.5625= $2.3125 If the MPC of every person is 0.75, then the GDP increase is: $1 GDP $1 $1 0.75 $0.75 0.75 $4 1 0.75 GDP increases four times as large as the increase of government spending, so the multiplier is 4. The Multiplier The multiplier is the ratio of the change in the equilibrium level of output to a change in some autonomous variable. The Multiplier MPS may be expressed as: S MPS Y Because △S must be equal to △I for equilibrium to be restored, △I can be substituted for △S. I 1 MPS Y I Y MPS 1 1 Multiplier MPS 1 MPC The Multiplier AE2 = C+ I + G2 =150 + 0.75Y AE AE1 = C+ I + G1 =125 + 0.75Y 1 Multiplier 1 MPC 1 4 1 0.75 150 125 45º 500 600 Y The Tax Multiplier A tax cut increases disposable income, which is likely to lead to added consumption spending. Income will increase by a multiple of the decrease in taxes. However, a tax cut has no direct impact on spending. The tax multiplier for a change in taxes is smaller than the multiplier for a change in government spending. The Tax Multiplier 1 MPC Y ( T MPC) T MPS MPS MPC Tax Multiplier MPS Tax Multiplier MPC Expenditure Multiplier However, a tax cut has no direct impact on spending. The tax multiplier for a change in taxes is smaller than the multiplier for a change in government spending. The Crowding-Out Effect There are two macroeconomic effects from the change in government purchases: The multiplier effect The crowding-out effect The Crowding-Out Effect Fiscal policy may not affect the economy as strongly as predicted by the multiplier. An increase in government purchases causes the interest rate to rise. A higher interest rate reduces investment spending. The Crowding-Out Effect This reduction in demand that results when a fiscal expansion raises the interest rate is called the crowding-out effect. The crowding-out effect tends to dampen the effects of fiscal policy on aggregate demand. The Crowding-Out Effect AS Price Level Crowding-out effect= Q2 – Q3 P2 P3 P1 AD2 AD1 0 Q1 Q3 Q2 AD3 Quantity of Output The Paradox of Thrift When households are concerned about the future and plan to save more, the corresponding decrease in consumption leads to a drop in spending and income. In their attempt to save more, households have caused a contraction in output, and thus in income. They end up consuming less, but they have not saved any more. The Paradox of Thrift S, I 175 125 S2 75 S1 I 25 -25 -75 300 600 Y Assignment Review Chapter 22, 23, and 24 Answer questions on P430, 444 and 463. Search for information on China’s fiscal policies in the recent years. Preview Chapter 25 and 26 Thanks