* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Labour Economics and Socio

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

Vladimir Dahl East-Ukrainian National University

© Filippova I.H.

Demos of the discipline

ECONOMIC OF LABOUR

& SOCIO-LABOUR

RELATIONS

Emigration

Labor Migration

Immigration

© Filippova I.H.

ECONOMIC OF LABOUR & SOCIO-LABOUR RELATIONS

According

Organization

to

for

the

International

Migration's

World

Migration Report 2010, the number of

international migrants was estimated at

214 million in 2010. If this number

continues to grow at the same pace as

during the last 20 years, it could reach

World Population:

6,853,328,460

Migrants in the world:

215,738,321

Almost 3.15% of the world population live outside their countries

2

Migration

405 million by 2050.

ECONOMIC OF LABOUR & SOCIO-LABOUR RELATIONS

© Filippova I.H.

International migration will play an increasing role in the demographic future of

nations if fertility continues to decline in most countries.

Net immigration already accounts for roughly 40% of population growth in the

United States of America and about 90% in the EU-15 countries

3

International migration

ECONOMIC OF LABOUR & SOCIO-LABOUR RELATIONS

© Filippova I.H.

International labour migration is defined as the movement of people

from one country to another for the purpose of employment.

Labour

mobility

has

become a key feature of

globalization

global

and

economy

the

with

migrant workers earning

US$ 440 billion in 2011,

and

the

estimating

World

Bank

that

more

than $350 billion of that

total was transferred to

developing countries in

the form of remittances.

4

International Labour Migration

ECONOMIC OF LABOUR & SOCIO-LABOUR RELATIONS

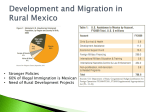

Recently, Ukraine has become

one of the major labor exporting

countries

in

Europe.

Rough

estimations of the workforce that

has at some time worked abroad

about 7 million people, which is a

lot in any case for Ukraine with

its work-capable population of

about 28 million.

5

Migration from Ukraine

© Filippova I.H.

© Filippova I.H.

ECONOMIC OF LABOUR & SOCIO-LABOUR RELATIONS

INDIA

5436012

AUSTRALIA

5522408

Top migrant

destination

FRANCE

6684842

SPAIN

6900547

UNITED KINGDOM

6955738

CANADA

7202340

SAUDI ARABIA

7288900

GERMANY

10758061

RUSSIAN FED

12270388

42788029

USA

0

6

7000000

14000000

21000000

Top migrant destination

28000000

35000000

42000000

49000000

© Filippova I.H.

ECONOMIC OF LABOUR & SOCIO-LABOUR RELATIONS

TURKEY

4261786

PHILIPPINES

4275612

UNITED KINGDOM

4666172

PAKISTAN

4678730

Top emigration

countries

5384875

BANGLADESH

UKRAINE

6525145

CHINA

8344726

RUSSIAN FED

11034681

INDIA

11360823

11859236

MEXICO

0

7

2000000

4000000

6000000

Top emigration countries

8000000

10000000

12000000

14000000

© Filippova I.H.

ECONOMIC OF LABOUR & SOCIO-LABOUR RELATIONS

•CHINA-USA

1736314

Top migration

•INDIA-UNITED ARAB

EMIRATES

2185919

•CHINA-HONG KONG

2224503

•RUSSIAN FED.KAZAKHSTAN

2226706

corridors

•KAZAKHSTAN-RUSSIAN

FED.

2648315

•TURKEY-GERMANY

2733109

•BANGLADESH-INDIA

3299268

•UKRAINE-RUSSIAN FED.

3647234

•RUSSIAN FED.-UKRAINE

3684217

•MEXICO-USA

11635995

0

8

2000000

4000000

6000000

Top migration corridors

8000000

10000000

12000000

14000000

© Filippova I.H.

ECONOMIC OF LABOUR & SOCIO-LABOUR RELATIONS

In countries, which do not share a long

and porous border with the destination

country and do not have extensive

networks leading to low-skilled jobs

there, international migration is more

costly and risky.

This precludes much emigration from

the low end of the skill distribution,

leaving a predominance of brain-drain

migrants at the top.

9

Migration's costs & risks

© Filippova I.H.

ECONOMIC OF LABOUR & SOCIO-LABOUR RELATIONS

Theories of migration try to

explain what drives

population flows.

Given the complex nature of

the

decision

process

individuals face, there is a

large variety

of

theoretical

models available to explain

the actual migration outcome.

While

micro

behavioural

models

focus

on

dominant factors at the individual level (such as

These models may either be

the human capital model), macroeconomic models

classifed

especially focus on the labour market dimension of

as

micro-

macroeconomic in nature.

10

or

migratory flows.

Theories of migration

© Filippova I.H.

ECONOMIC OF LABOUR & SOCIO-LABOUR RELATIONS

The neoclassical migration theory starts

from

The human capital model of migration in

expected

maximization approach.

fact views the process of migration as an

investment where the returns to migration

(in terms of higher wages associated with a

new job) exceed the costs involved in

moving.

From this follows that the humans compare

the expected income they would obtain for

the case they stay in their home region (X)

with the expected income they would

obtain in the alternative region (Y) and

further accounts for 'transportation costs' of

moving from region X to Y.

11

an

Neoclassical migration theory

income

(utility)

ECONOMIC OF LABOUR & SOCIO-LABOUR RELATIONS

© Filippova I.H.

Thus, neoclassical economic theories of labor migration posit that individuals situate

themselves in the labor market and jobs where their expected earnings (net of migration

costs) are highest. Earnings are the product of wages and time worked, both of which

depend on education and other “human capital” characteristics of individuals. Other

considerations affecting individuals’ satisfaction or “utility” at different locales (e.g.,

proximity to family members, relative deprivation, family income risk) also affect migration

propensities in neoclassical models.

The

association

between

characteristics of individuals and

their likelihood of

migrating

frequently

to

referred

as

is

the

“selectivity” of migration.

12

Selectivity of migration

© Filippova I.H.

ECONOMIC OF LABOUR & SOCIO-LABOUR RELATIONS

Social

science

research

the

For example, in most cases, average

determinants of migration using household

schooling levels for immigrants in the

level data generally find that human capital

U.S. are substantially above those of

(e.g., education) is positively related to the

their countries of origin. This finding

likelihood of out-migration.

reflects higher economic returns to

The selectivity of migration on individual and

schooling in the U.S. compared to

household

places of origin as well as other

characteristics

on

varies

across

migrant destinations. It depends critically on

potential

the returns to these characteristics in

urban areas in migrants’ countries of

different migrant labor markets.

origin).

migrant

destinations

(e.g.,

It also has implications for development.

If migrants take (human) capital with

them when they migrate, this may have

detrimental effects on the productivity of

workers left behind.

13

Human capital as the factor of migration

ECONOMIC OF LABOUR & SOCIO-LABOUR RELATIONS

© Filippova I.H.

The Lewis dual economy consists of a "capitalist" sector and a

"non-capitalist" sector.

Although Lewis did not intend this, in practice the capitalist sector

has generally become identified with the urban economy and the

non-capitalist sector with agriculture or the rural economy.

Sir W. Arthur Lewis

Though neoclassical two-sector models originally designed to

examine the reallocation of labor between rural and urban areas, it is

potentially applicable to international migration.

14

Lewis dual economy

© Filippova I.H.

ECONOMIC OF LABOUR & SOCIO-LABOUR RELATIONS

The capitalist sector hires labor and sells

Profit

output for a profit, while the non-capitalist

(or subsistence) sector does not use

reproducible capital and does not hire labor

for a profit.

Capitalist

Initially, labor is concentrated in the non-

sector

capitalist sector. As the capitalist sector

expands, it draws labor from the noncapitalist sector.

Labor

If the capitalist economy is concentrated in

the urban economy, labor transfer implies

geographic movement, i.e., rural-to-urban

migration.

15

Dual economy

Subsistence

sector

© Filippova I.H.

ECONOMIC OF LABOUR & SOCIO-LABOUR RELATIONS

In theory, migration implies an opportunity

Opportunity cost

for the rural

economy

cost for the rural economy, which loses the

product of the individuals who migrate.

However, the centerpiece of the Lewis

model

(and

essence

of

the

classical

approach) is the assumption that labor is

available to the industrial sector in unlimited

In the limiting case, this implies that there

quantities at a fixed real wage, measured in

is surplus or redundant labor in rural

agricultural goods.

areas, such that the marginal product of

rural labor is zero, and labor thus may be

withdrawn from rural areas and employed

in the urban sector without sacrificing any

loss in agricultural output. That is, the

opportunity cost or "shadow price" of rural

labor to fill urban jobs is zero.

16

Opportunity cost for the rural economy

© Filippova I.H.

ECONOMIC OF LABOUR & SOCIO-LABOUR RELATIONS

More generally, the labour supply from

In the Lewis model, earnings at the

the subsistence sector is unlimited if the

prevailing capitalist-sector wage must

exceed

the

labour supply is infinitely elastic at the

non-capitalist-sector

ruling capitalist-sector wage.

earnings of individuals willing to migrate.

Any tendency for earnings per head to

rise in the non-capitalist sector must be

offset by increases in the labor force

W

LD

there (e.g., through population growth,

female

labor-force

participation,

or

LS

immigration).

A key hypothesis of the Lewis model is

that

rural

accompanied

out-migration

by

a

is

decrease

not

in

agricultural production nor by a rise in

either rural or urban wages.

17

Key hypothesis of the Lewis model

L

ECONOMIC OF LABOUR & SOCIO-LABOUR RELATIONS

© Filippova I.H.

According to Ranis and Fei’s interpretation of the Lewis

model, the perfectly elastic labor supply to the capitalist

sector ends once the redundant labor in the rural sector

disappears and a relative shortage of agricultural goods

emerges.

Through migration, the marginal value products of labor

are equated between the two sectors. Here the Lewis

classical approach ends and the neoclassical analysis

starts. The dual economies merge into a single economy

in which wages are equalized across space.

Assuming full employment of labor in both rural and urban sectors and minimal transactions

costs, inter-sectoral wage differentials should be the primary factors driving rural outmigration.

18

Gustav Ranis & John Fei

© Filippova I.H.

ECONOMIC OF LABOUR & SOCIO-LABOUR RELATIONS

Rural-to-urban migration exerts upward pressure on wages and on the marginal value

product of labor in rural areas, while putting downward pressure on urban wages.

W

W

LD

W1

U

0

W

R

S

LS

LD

L

migration

W2R

W1U

Labor drawn

W0R

R

1

L

R

0

L

L

U

0

L

Rural-to-Urban Migration

Rural sector

19

Rural-to-Urban Migration

U

1

L

Urban sector

L

© Filippova I.H.

ECONOMIC OF LABOUR & SOCIO-LABOUR RELATIONS

Internal

and

international

migration

are

modeled according to this perfect-markets

neoclassical specification in virtually all

computable general equilibrium models, both

national and international.

In contrast, most microeconomic models of

rural out-migration are grounded on Todaro's

seminal work, which incorporates labormarket

imperfections,

including

urban

unemployment, into a migration model.

Michael P. Todaro

20

Michael P. Todaro

© Filippova I.H.

ECONOMIC OF LABOUR & SOCIO-LABOUR RELATIONS

Todaro proposed a modification of the neoclassical migration model in which each

potential rural-to-urban migrant decides whether or not to move to the city based on an

expected income maximization objective.

Expected urban income at a given locale is the product of the wage (the sole determinant

of migration in the neoclassical models), and the probability that a prospective migrant will

succeed in obtaining an urban job. Expected rural income is calculated analogously.

Individuals are assumed to migrate if their discounted future stream of urban-rural

expected income differentials exceeds migration costs; i.e., if

T

e t pu (t ) yu yr (t )dt c 0

0

pu (t )

is the probability of urban employment at time t,

yu

denotes urban earnings given employment,

yr (t )

represents expected rural earnings at time t,

21

Michael P. Todaro

c

is migration costs,

is the discount rate.

ECONOMIC OF LABOUR & SOCIO-LABOUR RELATIONS

© Filippova I.H.

Among nations, the share of rural population declines sharply as per-capita incomes

increase, from 70 to 80% in countries with the lowest per-capita GNPs to less than 15%

in the highest-income countries.

22

Share of rural population & GNP pc

ECONOMIC OF LABOUR & SOCIO-LABOUR RELATIONS

© Filippova I.H.

The share of the national workforce in agriculture plunges even more sharply, from 90%

or higher in low-income countries to less than 10 % in high-income countries.

23

The share of the national workforce in agriculture

ECONOMIC OF LABOUR & SOCIO-LABOUR RELATIONS

In the United States an estimated 69 % of the 1996 seasonal

agricultural service workforce was foreign-born, and in

California, the nation's largest agricultural producer, more

than 90 % of the seasonal agricultural service workforce was

foreign-born.

24

Foreign seasonal agricultural service workforce

© Filippova I.H.

ECONOMIC OF LABOUR & SOCIO-LABOUR RELATIONS

© Filippova I.H.

The world's great migrations out of rural areas are accelerating. The most populous

countries also are among the most rural. The greatest migration potential is in China,

where 71 % of the population is rural and an estimated one-third of the rural labor force

of 450 million is either unemployed or underemployed.

25

World migrations out of rural areas

ECONOMIC OF LABOUR & SOCIO-LABOUR RELATIONS

© Filippova I.H.

Human capital models

of migration represent

an effort to provide the

migration

theories

presented above with a

micro

grounding,

permitting tests of a far

richer set of migration

determinants

and

impacts.

The predictions of Human capital migration theory

26

Human Capital Theory and Migration

© Filippova I.H.

ECONOMIC OF LABOUR & SOCIO-LABOUR RELATIONS

The predictions of Human capital migration theory

First, the young should be more mobile

than the old, inasmuch as they stand to

get returns from migration over a longer

period of time.

Second, migration between locales should be negatively related

to migration costs. This has been interpreted as implying a

negative association between migration flows and distance.

However, considerations besides distance (especially access to

information) may make distance less of a deterrent for some

individuals

(e.g.,

better-educated

individuals

or

those

with

"migration networks", contacts with family or friends at prospective

migrant destinations).

27

The predictions of Human capital migration theory

ECONOMIC OF LABOUR & SOCIO-LABOUR RELATIONS

© Filippova I.H.

The predictions of Human capital migration theory

Third, neutral productivity growth in an economy - e.g.,

equal rates of growth in the rural and urban sectors -

will increase migration from low-income (e.g., rural) to

high-income (e.g., urban) sectors or areas.

Fourth, specific human capital variables that yield a higher

return in region A than in region B should be positively

associated with migration from B to A.

In addition to these predictions, human capital theory

implies that income differentials between rural and urban

areas are eliminated by migration over time.

28

The predictions of Human capital migration theory

© Filippova I.H.

ECONOMIC OF LABOUR & SOCIO-LABOUR RELATIONS

Labor Migration

W

If the countries are closed,

there are no migration flows

W

LS

LD

D

L

W1

LS

emigration

immigration

B

0

W

A

W1 A

W0A

W1B

S

1

L

A

0

L

D

1

L

L

Country A

29

B

0

L

Country B

Equilibrium model of migration

B

1

D

1

L L

L

ECONOMIC OF LABOUR & SOCIO-LABOUR RELATIONS

© Filippova I.H.

Migration not only produces lost-labor, and possibly also lost-capital, effects on rural

economies. It also represents a potentially important source of income and savings,

through migrant remittances. Non-migrants benefit from emigration, even if they do not

receive any of the remittances themselves, provided that the magnitude of migrants'

remittances exceeds a critical threshold roughly equal to the value of the production they

would have produced had they stayed behind.

Measuring

remittances

is

difficult

because migrants often enter developed

countries outside of official channels and

repatriate their earnings through informal

means. Money may be returned in the

form of goods purchased abroad or in

the form of cash savings brought back

by migrants or visiting family members

("pocket transfers").

30

Migrant remittances

© Filippova I.H.

ECONOMIC OF LABOUR & SOCIO-LABOUR RELATIONS

Causes of

Impacts of

migration

migrations

on sending countries

Analysis

on receiving countries

of

migration

in migrants and their

s

families

TOWARDS AN ASSESSMENT OF MIGRATION, DEVELOPMENT AND HUMAN RIGHTS LINKS:

CONCEPTUAL

FRAMEWORK

AND

NEW

STRATEGIC

http://www.un.org/esa/population/meetings/ninthcoord2011/assessmentofmigration.pdf

31

The Modern Approach to analysis of Migration

INDICATORS

© Filippova I.H.

ECONOMIC OF LABOUR & SOCIO-LABOUR RELATIONS

IMPACTS ON

Economic impacts

of remittances

SENDING

Impacts of return

migration

COUNTRIES

Social costs of

Demographic

reproduction

impacts

(human capital)

Demographic

Social and cultural

impacts

impacts

Political impacts

32

IMPACTS ON SENDING COUNTRIES

© Filippova I.H.

ECONOMIC OF LABOUR & SOCIO-LABOUR RELATIONS

Economic asymmetries

between sending and

Causes of

migration

receiving countries

Relative economic productivity

Social inequalities between

sending and receiving

countries

Human development index

between sending and receiving

countries

GINI coefficient

Differences in economic growth

Wage differentials

Labor precariousness in sending

and receiving countries

Deficit or surplus in labor force

Gaps in research and

development investments

33

Causes of Migration

Gender inequalities

© Filippova I.H.

ECONOMIC OF LABOUR & SOCIO-LABOUR RELATIONS

IMPACTS ON

Economic impacts

RECEIVING

Impacts on national

security

COUNTRIES

Demographic

Social and cultural

impacts

impacts

34

IMPACTS ON RECEIVING COUNTRIES

© Filippova I.H.

ECONOMIC OF LABOUR & SOCIO-LABOUR RELATIONS

IMPACTS ON

Economic

MIGRANTS

Impacts on labor

impacts

AND THEIR

conditions

FAMILIES

Impacts on

Social and cultural

human rights

impacts

35

IMPACTS ON MIGRANTS AND THEIR FAMILIES

ECONOMIC OF LABOUR & SOCIO-LABOUR RELATIONS

THE END

36

The end

© Filippova I.H.

![Chapter 3 Homework Review Questions Lesson 3.1 [pp. 78 85]](http://s1.studyres.com/store/data/007991817_1-7918028bd861b60e83e4dd1197a68240-150x150.png)