* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Tuberculosis: A Global Epidemic

Polysubstance dependence wikipedia , lookup

Psychopharmacology wikipedia , lookup

Discovery and development of non-nucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitors wikipedia , lookup

Drug interaction wikipedia , lookup

Prescription costs wikipedia , lookup

Pharmaceutical industry wikipedia , lookup

Pharmacogenomics wikipedia , lookup

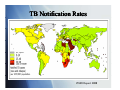

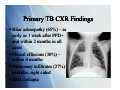

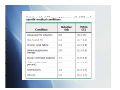

Tuberculosis: A Global Epidemic International Health Seminar Series April 27, 2010 Teresa Bleakly Allison Hill Sid Mahapatra Epidemiology > 2 billion p people p infected ((1/3 world population) 14.4 million with active infection 9.2 million new cases per year 1.7 million deaths per year worldwide Global incidence peaked in 2003, declined since TB Notification Rates WHO Report 2008 TB in children 884,019 cases under age 15 in 2000 (11% of total cases)) US: 1.3/100,000 in 2007 (6% of total cases) Higher rates in children < 5 years Declining rate in the US Most born in the US Infected by household contacts Primary TB Presentation Formerly mostly in children, now seen in teens and adults due to INH therapy py Fever (70%) – generally low grade, lasting 22-3 3 weeks Chest pain (±pleuritic) – retrosternal and interscapular Fatigue, cough, athralgias, pharyngitis less common Primary TB CXR Findings Hilar Hil adenopathy d th (65%) – as early as 1 week after PPD+ andd within ithi 2 months th in i all ll cases Pleural effusions (30%) – within 4 months Pulmonary infiltrates (27%) – pperihilar, right g sided RML collapse Reactivation TB 90% of adult cases in non-HIV infected population Cough, weight loss, fatigue (50-67%) Cough initially mild, in AM, non-productive Cough progresses to continuous, productive Fever, night g sweats (50%) ( ) Chest pain, dyspnea (33%) Hemoptysis (25%) Reactivation TB Usually normal labs Late disease: normocytic anemia, leukocytosis, monocytosis, t i SIADH, SIADH hhypoalbuminemia, lb i i hyerpgammaglobulinemia CXR Apical posterior segment of upper lobe infiltrate (80-90%) Atypical: hilar adenopathy, middle/lower infiltrates, pleural effusions solitary nodules (13-30%) effusions, (13 30%) Normal (10%) Extrapulmonary Manifestations GU: dysuria, hematuria, frequency, painful scrotal p pass,, prostatitis, p , orchitis Joints: osteoporosis, sclerosis, vertebral (Pott disease) CNS: AMS, neck stiffness, increased ICP, cranial nerve involvement TB meningitis or tuberculoma Other: O h llymphadenopathy, h d h choroidal h id l tubercle b l TB in children Pulmonary: most frequent manifestations Chronic cough Fever for > 2 weeks Weight loss, loss FTT Extrapulmonary Lymphadenopathy, adenitis g (neonates ( with highest g risk)) Meningitis Pleural/pericardial effusion Ascites, unexplained chronic diarrhea Nontender joint effusion Vertebral gibbus deformity Warty lesions Sterile pyuria, hematuria Iritis, optic neuritis, phlyctenular conjunctivitis Gibbus Deformity Perinatal TB Mortality of congenital/neonatal TB 50% Congenital TB Associated with TB endometritis or disseminated TB in mothers Acquired hematogenously via placenta or by aspiration asp at o of o amniotic a ot c fluid ud Resp distress, fever, HSM, poor feeding, lethargy, gy, irritability, y, LBW Risk Factors Substance abuse Nutritional status Underwt, U d Vi Vit D ddeficiency, fi i Fe deficiency Systemic diseases Silicosis, malignancy, DM, renal dz, gastric surgery, celiac dz Immune I compromise i HIV, steroids, TNF inhibitors, transplant Age Developing world = young adults Developed world = elderly Gender Male>Female Socioeconomic status Ethnic minority TB and HIV Increased risk of TB with HIV infx Risk doubles w/in 1st year, then progressively increases with decreasing CD4 count HIV accelerates progression of TB Increased risk of AIDS or death TB --> generalized immune activation --> increase CD4 cell circulation --> targeted by HIV Increased CCR5 and CXCR4 (HIV coreceptors) with TB coinfection TB associated with increased HIV viremia Viremia Vi i usually ll declines d li with ith successful f l TB treatment t t t TB and d HIV V Clinical Manifestations Early HIV: present similar to HIV neg pts Risk of extrapulmonary and disseminated TB greater with increased immunosuppression Lymph nodes, pleura TB and HIV Diagnosis PPD CD4 count >350: PPD + strongly suggestive of TB CD4 count <350: PPD not reliable li bl Not useful for diagnosing active TB where prevalence is high g Most important test: repeated sputum samples for smear andd culture, l andd lymph l h node d aspiration i i Normal CXR does not eliminate possibility of TB QuickTime™ and a Diagnosis of TB QuickTime™ and a TIFF (Uncompressed) decompressor are needed to see this picture. CXR In HIV-positive patients As CD4 count drops, more likely to have atypical CXR findings Non-cavitary y ppulmonary y infiltrates No preference for upper lung fields Normal CXR More common when CD4 <200 Chest CT - more sensitive Gastric aspiration Diagnosis of TB Sputum smear: sensitivity 45-80% HIV: Smear-negative pulmonary TB common d/t lower likelihood of pulmonary cavities A positive AFB is very specific for M. tuberculosis Sputum culture: sensitivity 85 85-100% 100% Lymph Node Biopsy FNA + in 75% of cases, bx with cx --> 96% Bronchoscopy To be avoided; aerosols of infectious droplets BUT it is a sensitive diagnostic technique AFB smears + in 50% of pts, culture + in ~100% Diagnosis of TB Fluorescence microscopy (FM) Comparable specificity to smears, smears but ~10% greater sensitivity FM (vs. smears) may be more cost-effective and expedite dit dx d in i resource poor areas Urine culture 77% of HIV pos pts w/ extrapulmonary TB grew M. tuberculosis CSF, pleural, pericardial, and peritoneal fluid High protein, low glucose, lymphocytosis, (elevated ADA) PCR Sensitive for rapid detection in blood, sputum, or urine Treatment of Latent TB I f i Infection Indications for treatment PPD > 5mm HIV Recent contacts of a TB case Persons with fibrotic changes on CXR consistent with old TB Transplant patients Immunosuppressed PPD > 10mm Recent arrivals (< 5 years) from high-prevalence countries IV drug users Residents and employees of high-risk congregate settings (e.g., correctional facilities, nursing homes, homeless shelters, hospitals, and other health care facilities) Mycobacteriology laboratory personnel Children < 4 years of age, or children and adolescents exposed to adults in high-risk categories PPD > 15 mm (none of the above risk factors) Treatment – Daily INH for 9 months Treatment of Active Disease Initial Phase (8 weeks) Daily INH, RIF, PZA, and EMB for 56 doses Continuous phase (18 weeks) Daily INH and RIF for 126 doses or Twice-weekly INH and RIF for 36 doses Monthly sputum specimens Monthly intervals until two consecutive specimens are negative on culture Monitor for adverse effects At end of initial phase to determine length of continuous phase Directly observed therapy (DOT) Health care worker or another designated person watches the TB patient swallow each dose of the anti-TB drugs. All patients taking drugs fewer than 7 days per week (e.g., 1, 2, 3, or 5 days a week) must receive DOT. Multi-Drug Multi Drug Treatment Rationale Patient with extensive pulmonary TB has approximately 10 12 bacteria in his bod body. Frequency of spontaneous mutations conferring resistance to an individual g drug: 1 in 107 for EMB 1 in 108 for STM and INH 1 in 1010 for RMP Chances of harboring a bacterium that is spontaneously resistant to both INH and RMP is 1 in 106. Chances of harboring a bacterium that is p y resistant to all four drugs g is 1 in 1015. spontaneously Different drugs in the regimen have different modes of action. Using only single drugs result in rapid development of resistance and treatment failure. Resistant TB Emergence Patients P ti t who h do d nott complete l t their th i full f ll course off treatment t t t Health-care providers prescribe the wrong treatment, the wrong dose, or wrong length of time for taking the drugs Supply of drugs is not available Drugs are of poor quality Drug-resistant tuberculosis (TB) M. tuberculosis resistant to at least one first-line anti-TB drug. Multidrug-resistant M ltid i t t TB (MDR TB) resistant i t t to t more than th one anti-TB ti TB drug d andd att least l t isoniazid (INH) and rifampin (RIF). Should be managed by or in close consultation with an expert. D Drug resistance it proven by b drug-susceptibility d tibilit testing t ti Can take weeks Start with an empirical treatment regimen When the testing results are known, the treatment regimen should be adjusted according Di tl observed Directly b d therapy th (DOT) always l should h ld bbe used d iin th the ttreatment t t off drugd resistant TB to ensure adherence. Special Considerations Children Guided by the source-case susceptibility results. If source unknown and circumstances suggest an increased risk of drug resistance, treat with standard four-drug initial-phase regimen until susceptibility pattern known. Ethambutol (EMB) can be used safely (15-20 mg/kg per day), in the likelihood of INH resistance. Streptomycin, p y , kanamycin, y , or amikacin also can be selected as the fourth drug. Long-term use of fluoroquinolones in children has not been approved. However, most experts agree that these drugs should be considered for children with MDR TB TB. Consultation with a specialist in pediatric TB treatment is recommended HIV-positive ART dec decreases eases TB-related e ated death deat and a d reduces educes the t e risk s of o developing deve op g TB Risk of TB diminishes only when CD4 >500/microL References Bernardo, J, et al. Diagnosis of tuberculosis in HIV-seronegative patients. Up-To-Date. Last literature review version 18.1: January 2010. Updated: December 1, 2009. Cain, K, et al. An Algorithm for Tuberculosis Screening and Diagnosis in People with g J Med 2010;; 362;8. ; HIV. N Engl David HL (November 1970). Probability distribution of drug-resistant mutants in unselected populations of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Applied Microbiology 20 (5): 810–4. g Jr, CR, et al. Epidemiology p gy of tuberculosis. Up-To-Date. p Last literature Horsburgh review version 18.1: January 2010. Updated: Oct 6, 2009. Horsburgh Jr, CR. Priorities for the treatment of latent tuberculosis infection in the United States. N Engl J Med 2004; 350:2060. g of tuberculosis in HIV-infected Maartens, G, et al. Clinical features and diagnosis patients. Up-To-Date. Last literature review version 18.1: January 2010. Updated: December 18, 2009. Streptomycin treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis. British Medical Journal 2 (4582): 769–82. October 1948. WHO 2009 Global Tuberculosis Report. http://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/2009/annex_1/en/index.html http://www.cdc.gov/tb/topic/treatment/default.htm TB and HIV Clinical Manifestations 133 AIDS pts with TB at a single hosipital in NYC Typical primary TB pattern: 36% Reactivation TB pattern: 29% Miliary pattern: 4% Atypical TB pattern (diffuse infiltrates suggestive of PCP): 13% Minimal change: 5% Normal CXR: 14% More common when CD4 <200