* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

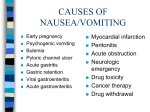

Download Antiemetics for reducing vomiting related to acute gastroenteritis in

Transtheoretical model wikipedia , lookup

Declaration of Helsinki wikipedia , lookup

Clinical trial wikipedia , lookup

Fetal origins hypothesis wikipedia , lookup

Epidemiology wikipedia , lookup

Forensic epidemiology wikipedia , lookup

Women's Health Initiative wikipedia , lookup