* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Constipation - Australian Medicines Handbook

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

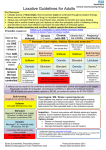

AMH Aged Care Companion Constipation Before starting treatment nt en t Constipation in older people is commonly associated with immobility and/or decreased fluid and fibre intake. Although whole gut transit time is unchanged in healthy, active older people, it is prolonged in immobile people. Other contributing factors include social conditions (eg lack of privacy, reliance on others for toileting assistance, change in surroundings), drugs, cognitive status and medical conditions (eg hypothyroidism, neurological disease, depression, perianal conditions). In older people, constipation may present as confusion, overflow diarrhoea, abdominal pain, urinary retention, nausea or loss of appetite. m pl e co Assess for faecal impaction and consider need for referral to exclude colon cancer in older patients with alarm symptoms or sudden change in bowel habit. Treat reversible causes, eg dehydration, depression, hypothyroidism, hypercalcaemia. The relationship between urinary incontinence and constipation can be complex: constipation may exacerbate urinary incontinence and treatment of urinary incontinence can lead to constipation, eg if fluid intake is decreased in an attempt to control urinary incontinence or if anticholinergic drugs are used. Assess for and manage urinary incontinence, see Urinary incontinence p 172. Stop causative drugs if possible, eg aluminium antacids, opioids, drugs with anticholinergic effects (p 236), calcium or iron supplements, diuretics, verapamil. Ensure an accurate bowel chart is kept, recording time, amount and consistency of stool; this is useful for assessing when laxatives are required and response to treatment. Sa Non-drug treatment Usually the first step in management, although evidence is limited; should be continued even if laxatives are used: – ensure adequate fluid intake (but consider risk of fluid overload in people with heart failure or renal impairment) – ensure adequate dietary fibre intake; increase intake gradually to avoid bloating and flatulence; consider dietetic review – toilet after meals or hot drink when gastrocolic reflex is maximal – increase exercise within the person’s abilities – improve access to toileting facilities – advise unhurried, complete defecation. For more detailed drug information, see the current edition of the Australian Medicines Handbook © Australian Medicines Handbook Pty Ltd www.amh.net.au AMH Aged Care Companion Drug treatment Sa m pl e co nt en t Management of constipation remains largely empirical; evidence supporting the use of laxatives is poor, particularly in the elderly. Both fibre and laxatives modestly improve bowel movement frequency in adults with constipation. There is inadequate evidence to establish whether fibre is superior to laxatives, or whether one laxative class is superior to another. Drug choice may be based on required onset of action, patient preference, adverse effects, effectiveness of previous treatments and cost, see Table 8 Comparison of laxative classes p 142. Whilst some cases of constipation may resolve with short-term use of laxatives, chronic laxative use is often required (eg in opioid-induced constipation, progressive neurological conditions, immobility); titrate dose to minimum required to achieve desired effect. Rapid relief of constipation: initial management of moderate-to-severe constipation may include suppositories, enemas, macrogol or saline laxatives to clear the rectum, followed by ongoing management. Ongoing management of constipation: promote regular bowel habits by using small regular doses of laxatives. Try bulk-forming laxatives for people who have a low-fibre diet, adequate fluid intake and are mobile. Osmotic and/or stimulant laxatives may be more appropriate for immobile people and those with decreased fluid intake. Opioid-induced constipation can be anticipated, so begin regular laxatives when starting opioid analgesia. Agents of choice include combined stimulant with stool softener (eg Coloxyl with Senna®) or osmotic laxatives (eg sorbitol or lactulose). Avoid bulk-forming laxatives and a high-fibre diet as increasing bulk may cause obstruction. For resistant cases use glycerol suppositories, small volume enemas, a macrogol laxative (eg Movicol®) or a saline laxative (see Safety considerations below). For palliative care patients, methylnaltrexone may be considered, see Palliative care issues p 71. Faecal impaction often presents as faecal soiling or overflow diarrhoea (usually small volume); management may include high-dose oral macrogol laxatives, suppositories, enemas and manual evacuation. Antidiarrhoeal agents should not be used to stop overflow diarrhoea. Regular laxatives may be required once impaction has been alleviated in addition to any lifestyle and dietary changes that can be made. Aged Care Companion © AMH 2016 © Australian Medicines Handbook Pty Ltd Constipation www.amh.net.au AMH Aged Care Companion Table 8 Comparison of laxative classes Laxative class Example Onset of action Place in treatment and safety considerations 2–3 days • ensure adequate fluid intake • contraindicated in intestinal obstruction, impaction, colonic atony; avoid in dysphagia • avoid in immobile or fluidrestricted older patients as can worsen constipation 1–3 days • use in opioid-induced constipation • contraindicated in intestinal obstruction • not suitable for acute relief of constipation due to slow onset of effect • flatulence is common ispaghula husk (eg Fybogel®)1; psyllium (eg Metamucil®)1; sterculia (eg Normafibe®)1 sorbitol (eg Sorbilax®)2; lactulose (eg Duphalac®)2 macrogol laxatives (eg Movicol® products); saline laxatives containing magnesium (eg Epsom Salts, Magnesia S Pellegrino®)1 0.5–3 hrs; 1–3 days (macrogol) Sa m pl e osmotic laxatives stool softeners 1 2 3 4 docusate (Coloxyl®)3 • some macrogol laxatives can be used for faecal impaction and constipation • magnesium salts are not recommended for regular use • limited evidence suggests macrogol laxatives may be more effective, and better tolerated, than lactulose in chronic constipation • risk of electrolyte disturbance and dehydration (less of a risk with macrogol laxatives than others, eg saline laxatives); use with caution in older people and in renal impairment or cardiovascular disease • contraindicated in intestinal obstruction (partial or complete), bowel perforation or threatened perforation (eg colitis), severe colitis (especially toxic megacolon) • avoid sodium phosphatecontaining laxatives, see Safety considerations p 143 co bulkforming laxatives nt en t Oral laxatives 2–3 days • may be used to reduce straining, eg in rectal surgery, acute perianal disease, ischaemic heart disease • use for opioid-induced constipation in combination with a stimulant laxative (eg Coloxyl with Senna®) dose according to label 15–30 mL once daily adjusted according to clinical response 50–150 mg once or twice daily up to 480 mg/day in divided doses 2.8 g rectally; allow to remain for 15–30 minutes For more detailed drug information, see the current edition of the Australian Medicines Handbook © Australian Medicines Handbook Pty Ltd www.amh.net.au AMH Aged Care Companion Laxative class Example Onset of action Place in treatment and safety considerations 6–12 hrs • can be used for acute or chronic (eg in neuromuscular disease) constipation • contraindicated in intestinal obstruction, acute abdominal conditions and inflammatory bowel disease • may cause abdominal discomfort and cramping • increased risk of faecal incontinence in elderly patients • ensure adequate fluid intake with products that also contain a bulk-forming laxative (eg Normacol Plus®, Agiolax®) stimulant laxatives bisacodyl (eg Bisalax®)1; frangula bark (in Normacol Plus®)1; senna (eg Senokot®)1 nt en t Oral laxatives (continued) Rectal laxatives glycerol suppository4; saline microenema (eg Microlax®) 5–30 mins (glycerol); 2–30 mins (saline laxatives) stimulant laxatives bisacodyl microenema or suppository (eg Bisalax®) 5–60 mins 1 2 3 4 • rectal laxatives may be indicated for occasional use, eg in faecal impaction or if there is insufficient response to oral laxatives • avoid embedding suppositories in faecal matter (delays effect) • avoid sodium phosphate enema (eg Fleet®), see Safety considerations p 143 co osmotic laxatives dose according to label 15–30 mL once daily adjusted according to clinical response 50–150 mg once or twice daily up to 480 mg/day in divided doses 2.8 g rectally; allow to remain for 15–30 minutes pl e Safety considerations Sa m Saline laxatives contain ions such as magnesium, sulfate, phosphate and citrate; they may cause electrolyte disturbances. Use with caution in older people, and avoid in renal impairment or cardiovascular disease. Laxatives containing sodium phosphate (eg Fleet®, Diacol®) should not be used in the elderly; they can cause serious fluid and electrolyte disturbance, including hypocalcaemia, hyperphosphataemia and hypokalaemia. Acute renal failure (including acute phosphate nephropathy), cardiac arrest and deaths have been reported. There is a greater risk of adverse effects in patients >55 years, in dehydrated patients, or in those being treated with diuretics, ACE inhibitors, sartans or NSAIDs. Sodium phosphate laxatives are contraindicated in heart failure or renal impairment. Some macrogol products contain sodium (eg Movicol® contains approximately 8.1 mmol (186 mg) sodium per sachet; Movicol-Half® and Movicol Junior® sachets contain approximately half this); consider impact of sodium intake in certain patients (eg those with heart failure). Aged Care Companion © AMH 2016 © Australian Medicines Handbook Pty Ltd Constipation www.amh.net.au AMH Aged Care Companion Practice points • • • Sa m pl e • nt en t • glycerol is also known as glycerin laxatives are also referred to as aperients encourage person to sit on the toilet with both feet supported on floor or foot stool, leaning forward slightly so abdomen falls away from body relaxing pelvic floor muscles, as this will help reduce the need for straining stool softeners have little value used alone in chronic constipation or constipation from opioids be aware of difficulties for older people in the community or lowlevel care facilities; they may not use non-drug options because: – they feel unsafe going out alone to exercise – fruit and vegetables may be too expensive – they believe increased fluid intake may worsen urinary incontinence cost may be a problem, especially if long-term laxative use is needed; not all laxatives are subsidised by the PBS and restrictions may apply to those that are there is no convincing evidence that chronic use of stimulant laxatives causes atony, aperistaltic colon or colonic injury prucalopride is approved for treatment of chronic idiopathic constipation when other regular laxatives are inadequate; in a 4-week study in people >65 years (70% female), the recommended dose was not significantly better than placebo in achieving the primary endpoint (3 or more spontaneous complete bowel movements per week) at any point during the trial; further study is needed to establish its role in the management of constipation in older people co • • • For more detailed drug information, see the current edition of the Australian Medicines Handbook © Australian Medicines Handbook Pty Ltd www.amh.net.au