* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download CLINICAL PRACTICE Anaesthetist`s responses to patients` self

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

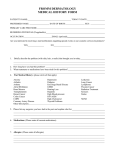

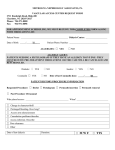

British Journal of Anaesthesia 97 (5): 634–9 (2006) doi:10.1093/bja/ael237 Advance Access publication September 1, 2006 CLINICAL PRACTICE Anaesthetist’s responses to patients’ self-reported drug allergies R. D. MacPherson1 *, C. Willcox2, C. Chow2 and A. Wang1 1 Department of Anaesthesia and Pain Management and 2Department of Pharmacy, Royal North Shore Hospital, Pacific Highway, St Leonards, NSW 2065, Australia *Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] Background. Patients with drug allergies are commonplace in anaesthetic practice. We investigated the incidence and nature of drug ‘allergies’ reported by surgical patients attending a hospital pre-admission clinic, and went on to ascertain to what degree drug allergies recorded in the records influenced drug prescribing during the patients’ hospital stay and determine whether any adverse events occurred in relation to drug prescribing in this population. Methods. Patients attending for anaesthetic assessment at a Pre-Admission Clinic over a 30 week period were questioned concerning drug allergies. Medical records of these patients were then examined after their hospitalization to assess medications prescribed during that period. Results. Of 1260 patients attending the Pre-admission clinic during the study period 420 (33.4%) claimed to have a total of 644 individual drug ‘allergies’. The most common agents implicated were antibiotics (n=272), opioid analgesics (n=118) and NSAIDs (n=62); the most common form of these reactions were dermatological (n=254) and nausea and vomiting (n=124). There were 41 self-reports specifically of anaphylaxis and a further 61 where there was significant respiratory system involvement. Conclusions. The majority of the self-reported allergies were in fact simply accepted adverse effects of the drugs concerned. The patients’ reported drug ‘allergy’ history was generally well respected by anaesthetists and other medical staff. There were 13 incidents, mainly involving morphine, where patients were given a drug to which they had claimed a specific allergy. There were 101 incidents in 89 patients where drugs of the same pharmacological group as that of their allergic drug were used. There were no untoward reactions in 84 patients who had claimed a prior adverse reaction to penicillin who were given cephalosporins. There were no sequelae from any other events. While anaesthetists generally respected patients self-reported ‘allergies’, more attention needs to be paid to the accurate recording of patients’ events and a clear distinction should be made both in medical records and to the patient between true drug allergy and simple adverse drug reactions. Br J Anaesth 2006; 97: 634–9 Keywords: complications, adverse drug reaction; complications, allergy Accepted for publication: June 29, 2006 Taking a drug history is an integral part of any medical admission, and within that history it is important to elicit from the patient reports of previous adverse drugs effects or drug allergies, as these details will obviously influence drug selection and therapeutic decision making. Unfortunately, the reliability and details of such self-reported allergies are often questionable, and furthermore these details are often recorded in a perfunctory manner. The aims of the present study were 3-fold. First, to examine in detail self-reported drug allergies in a surgical patient population, and to determine the extent to which these events were likely to be true drug allergy as opposed to a simple adverse drug effect. Then, by examination of patient medical records, to ascertain to what degree patient reported allergy had influenced prescribing and whether any adverse events occurred because of inappropriate prescribing. Methods After approval from the Hospital Ethics Committee, as part of their routine admission, all patients attending the PreAdmission Clinic at this hospital were questioned by an The Board of Management and Trustees of the British Journal of Anaesthesia 2006. All rights reserved. For Permissions, please e-mail: [email protected] Anaesthesia and drug allergies attending pharmacist (C. W. or C. C.) using a formatted questionnaire as to whether they had any drug allergies to report. If the response was positive, patient characteristic data were recorded, and the exact nature of the reaction and how long ago the reaction occurred. These patient allergies were recorded in the usual manner on the Patient Medication Chart. After discharge from hospital, the medical records of these patients were examined to ascertain what drugs were administered during their admission and whether any of these medications might conflict with those reported as allergies from the patient allergy list. Results During the 30 week period, a total of 1260 patients attended the Hospital PAC for assessment before surgery. Of these 431 (29.1%) claimed to have at least one drug allergy and underwent further assessment by a pharmacist. Eleven patients were excluded. In nine patients this was because their allergy was not to a drug but rather to either surgical dressings or foodstuffs. The remaining 2 cases were patients who each claimed to have more than 40 different drug allergies. Unfortunately, of the list presented, in many instances these patients had not received all of these drugs at all, but rather had created lists of drugs to which they felt they might be allergic. It proved impossible to determine from these patients’ histories which drugs they had been exposed to and which ones were simply ‘suspected’ allergens. Therefore 420 patients were finally admitted to the study. The patient characteristics of the group showed a female preponderance (females 269, males 139) with a mean overall age of 62.6 yr (range 19–95 yr). Preoperative assessment A total of 644 reactions were reported by the 420 patients finally enrolled in the study. Mild reactions such as rash or pruritus (n=254) or nausea and vomiting (n=124) constituted the bulk of reports (Table 1). Of the serious reports, there were 41 self-reports specifically of anaphylaxis [penicillins (n=21); sulphonamides (n=4); NSAIDs (n=2)] and a further 61 reports of potentially serious events involving respiratory distress, upper airway obstruction or oro-facial oedema. Although there is clearly considerable possibility of crossover between the anaphylaxis and Table 1 Nature of adverse reactions to drugs as described by patients (n=number of reports) Type of reaction n Rash/pruritis Nausea/vomiting CNS/hallucinations Oedema/swelling Anaphylaxis Extrapyramidal symptoms Other reactions Could not recall 254 124 64 61 41 8 54 38 ‘breathing/oedema’ categories, only patients who specifically stated anaphylaxis as their type of reaction were included in the former category. Of this group, the most common drugs implicated again were antibiotics with 31 reports [penicillins (n=14); sulphonamides (n=12), other antibiotics (n=5)], non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (n=8) and opioids (n=3). There were 38 cases in which the patient stated they had suffered an adverse reaction to a particular drug, but had forgotten details of the event and could offer no further information. Table 2 shows the most common drugs implicated in these reactions with antibiotics (n=272) and opioid analgesics (n=118) being the most common. Of importance to anaesthetists, other common agents to which allergy was reported included NSAIDs (62), phenothiazines (13) and tramadol (12). Of six patients who claimed to be ‘allergic’ to general anaesthesia, all in fact were reporting postoperative nausea and vomiting. The time course of these reactions was also investigated. Although the majority (n=317) had occurred within the last 10 yr, patients continued to report reactions that had occurred 30 (n=570), 40 (n=47) or even 50 yr earlier (n=37). In 124 cases, the patient could not recall when the reaction had occurred. Postoperative assessment The aim of this part of the study was to examine to what degree patients’ self-reported drug allergies were respected with regard to medication prescription. Of the original 420 patients enrolled in the study, records for 400 were selected for further examination. Twenty patients were excluded from the second part of the study either because the patient did not proceed to surgery (n=9), or because the patient medical record could not be located (n=11). In the majority of cases (n=298), patients were not given drugs to which they had stated a specific drug allergy. There were 101 instances in 89 individuals where drugs were selected from related groups, presumably in an effort to avoid the ‘allergic’ drug (Table 3). The most common event was Table 2 Drugs to which patients claimed they had previous adverse or ‘allergic’ reactions (n=number of individual reports) Drug n Antibiotic Penicillin Sulphonamides Cephalosporins Erythromycin Tetracyclines Other Opioids NSAIDs Iodine Vaccines Phenothiazines Tramadol Steroids Other 272 147 60 15 12 8 30 118 62 24 14 13 12 7 122 635 MacPherson et al. Table 3 The left column (Stated allergy) lists drugs to which patients had claimed a previous adverse reaction. The middle column shows drugs of similar pharmacological activity administered to these patients. The right column lists number of instances Stated allergy Drug given Penicillin Penicillin Penicillin Prochlorperazine Pethidine Atropine Atropine Antibiotics Anaesthetics Codeine Omeprazole Indomethacin Indomethacin Cephazolin Cefotetan Ceftriaxone Metoclopramide Morphine Hyoscine Glycopyrrolate Gentamicin GA Tramadol Esomprazole Rofecoxib Diclofenac n 73 7 4 2 2 1 1 1 6 1 1 1 1 the use of cephalosporins in patients who self-reported a preexisting adverse reaction to penicillin (n=84). However, in a small number of cases (n=13) there was evidence that the patient was administered either the drug to which they had claimed they were allergic or an agent of very close pharmacological similarity. In six of these cases, morphine was administered to patients who had claimed a previous allergy to the drug. In the other cases, penicillin was given to two patients with a claimed penicillin allergy, and codeine (three), tramadol (one) and aspirin (one) were administered under similar circumstances. In none of these cases was there any evidence of any subsequent adverse reaction after administration. Discussion An integral part of the medical or anaesthetic assessment is an appraisal of any previous drug allergies or adverse drug reactions (ADRs). In the hospital setting, these same questions are often asked by multiple members of the health care team including nursing staff and pharmacists, but despite this, accurate recording of details does not always occur.1 While such data are usually then summarized as a simple list, further analysis often gives useful insight into the nature of these reactions. An ADR has been defined2 as any noxious, unintended and undesired side effect of a drug that occurs at doses used for prevention, diagnosis and treatment. However, Rawlins and Thompson3 have expanded this concept, and classified ADRs into two main categories, depending on their aetiology. Type A reactions are common and predictable. These are usually dose dependent and are produced by known and understood pharmacological actions of a drug. They include the effects of excessive dosage and secondary effects such as diarrhoea related to antibiotic use.4 Drug intolerance (an undesired effect produced by a drug at therapeutic or sub-therapeutic doses) is also included in this category. Type B reactions are defined as uncommon, usually unpredictable and dose-independent events. A range of other descriptors have been used to describe these events including idiosyncratic reactions (uncharacteristic reactions that are not explicable in terms of a drugs pharmacological action) and allergic or hypersensitivity reactions.5 Recently, the whole question as to what criteria should be present to constitute an allergic reaction has been re-examined. Expert groups6 7 have suggested that the term ‘drug hypersensitivity’ should be used as an umbrella term to cover the gamut of reactions, especially those involving the skin and mucous membranes. The term ‘allergy’ should be used only to describe reactions that have been demonstrated to be immunologically mediated, with all other events referred to as ‘non allergic hypersensitivity’. There is no doubt that analysis of ADRs and hence comparisons between studies have become more difficult. This is because of what one author8 has called a ‘Tower of Babel’ terminology, where over time definitions and terms have changed, with some categories (e.g. pseudo-allergy) being declared obsolete while other new categories (e.g. allergic protein contact dermatitis) have emerged. In part these changes reflect the growing understanding in the area of clinical immunology. Despite the limitations of the Rawlinson and Thompson classification, it remains in use by many authors as a means to simply classify ADRs.9 It has been suggested that in addition to the Type A and B reactions outlined above, a third group needs to be acknowledged. These are patients who experience an adverse event, such as nausea or vomiting, and wrongly ascribe this as being because of medication, when in fact it may be part of the disease process. The incidence of drug allergies and the distribution of Types A and B reactions using the Rawlins and Thompson classification has been widely studied. Taken in the broadest context, most studies have found that the incidence of selfreported drug allergy is in the order of between 25 and 39%.10–12 In one of these studies11 the rates of reported ADRs were assessed on admission. In 915 patients admitted over a 13 month period, 78 (8.5%) reported a total of 102 ADRs and 102 reactions. In 45 cases in this study, the adverse drug event was directly responsible for the patients’ admission. The most common drugs implicated were diuretics, analgesics, especially NSAIDs, and anti-psychotic agents. In another study, Jones and Como12 found the ADR rate in their sample (n=133) to be 39% with beta-lactam antibiotics (12.6%), sulphonamides (9.1%) and opioids (4.4%) being the most commonly implicated agents. When these ADRs are further examined, most studies have concluded that the majority of the self-reported drug reactions are of the Type A category. These constitute between 70 and 80% of reports13 14 with an undetermined group of about 10%. Our study supports these findings with Category A reactions (n=386) exceeding Category B reactions (n=152). In the remainder of cases (n=106) it was not possible to determine the nature of the reaction from the data supplied. The most common types of reactions were 636 Anaesthesia and drug allergies generally minor with dermatological and gastrointestinal reactions being the most common. Others have found conflicting results. In one study15 the investigators examined more than 1800 patients and found that 28% claimed to have one or more allergies. There was a clear female preponderance (60.3%). Commonly implicated drugs were antibiotics (50%), opioids (27%) and NSAIDs (10%). The rate of probably true allergic (Type B) reaction was higher than most at 50%. In another large prospective study of hospital admissions 366 cases of suspected drug allergy were reported during a 2 yr period16 and found the majority (57.4%) to be true allergic reactions, 19.7% idiosyncratic and 19.1% coincidental reactions. Despite changes in prescribing patterns over time, the most commonly reported drugs in our study are common to other earlier studies and include antibiotics and analgesics including opioids and NSAIDs,12 with the most common reactions being dermatological, another finding common to previous studies.14 16 17 It is generally accepted that penicillins are the most common cause of allergic drug reactions and anaphylaxis,18 with an incidence across the population as a whole of between 1 and 10%. However, it has been suggested that the vast majority of patients who report a penicillin allergy are not truly allergic19 and could safely receive the drug. Another large scale prospective study showed that of 1790 people with claimed penicillin allergy, only 57 (3.2%) demonstrated true penicillin allergy of which 4 were anaphylactic in nature.20 Much has been written on penicillin allergy and its consequences. It is clearly important to correctly identify the true nature of reactions in patients claiming ‘penicillin allergy’. Validation of true allergy using skin prick testing should be instituted where possible, as patients self-labelled as allergic may be treated with inappropriate antibiotics and hasten the spread of multiple drug resistant organisms.19 Anaphylactic reactions to penicillin, while still very rare,5 continue to account for more than 75% of all fatal anaphylactic drug reactions.21 22 When this reaction does occur, it is mainly in adults aged 20–49 yr.23 Interestingly, with the passage of time the risk associated with readministration of the drug decreases,24 with the incidence of positive skin test responses in previous anaphylaxis patients reducing by about 10% annually. Skin testing itself has a very variable sensitivity of between 20 and 70% depending on the determinant.25–27 The incidence of cross-sensitivity between penicillins and cephalosporins has been the subject of continued interest. The degree of cross-reactivity has been estimated at about 10% for first generation cephalosporins, but only 1–2% in third generation agents.28 29 In our study a range of cephalosporins [cephazolin (n=73), cefotetan (n=7) and ceftriaxone (n=4)] were given to 84 patients who believed they were allergic to penicillin with no adverse sequelae. Sulphonamide antibiotics are rarely prescribed nowadays, and most people stating allergy to these agents were older patients (mean age 61.7), reflecting changes in prescribing patterns. While occasional dermatological reactions such as Stevens–Johnson syndrome can be potentially life threatening, most common skin and gastrointestinal complaints to this drug group are generally minor. There is some disagreement concerning the incidence of cross-sensitivity between sulphonamides and other agents with structural similarities. While it is known that the para-amino benzoic acid moiety found in sulphonamides is also found in a range of other drugs such as COX-2 inhibitors, thiazide diuretics, sulphonylurea oral hypoglycaemic agents and diazoxide, it has been suggested that the risk of cross-reactivity would seem to be more of a theoretical rather than a clinical consideration.30 This is because the sulphonamide antibiotics contain an aromatic amine on the N4 position, necessary both for the drugs antimicrobial activity and allergenic propensity, a side chain that is lacking in these other drugs.31 NSAIDS are common producers mainly of gastrointestinal upset, a typical Type A reaction. While true allergic reactions are uncommon,32 this group of drugs has been implicated in more serious reactions such as NSAID induced asthma and urticaria/angio-oedema. Aseptic meningitis and hypersensitivity pneumonitis are other rare immunerelated reactions that have been reported.33 34 With regard to opioids, the majority of reactions are clearly of the Type A category and include, nausea, vomiting sedation and pruritus. These are clearly not ‘allergic’ in nature but it can be problematic to administer the drug again. Most anaesthetists in our study chose to avoid the offending drug (usually morphine) and selected another opioid. However, with the current trend against the use of meperidine35 the possibilities are becoming more limited. It is of interest to note that in our study, seven patients reported a reaction to corticosteroids (rash, 2; facial swelling, 2; hallucinations, 1; could not recall, 1). Steroid hypersensitivity reactions although rare are not unknown. In one review36 the authors noted that steroid reactions can vary from minor dermatological effects to complete cardiovascular collapse. The mechanisms involved are probably multiple with some being of a classic IgE response and some pseudo-allergic in nature. In this study, a total of 644 reactions were reported by 420 patients seen in a Pre-Admission Clinic, a result that concords with those of previous reports that suggest that approximately one-third of hospital patients will report at least one drug allergy. Patients have a tendency to venerate their drug allergies, with many of the reported reactions being of dubious importance and many having occurred more than 40 yr ago. Importantly, the most commonly reported drugs, antibiotics, opioids and analgesic agents such as NSAIDs and tramadol, are those that would normally be given as part of the anaesthetic or surgical admission. When called to anaesthetize these patients, the anaesthetist must decide whether to avoid reported ‘allergic’ drugs completely and use alternative agents or whether to investigate the selfreported ‘allergy’ in more detail. If further investigation 637 MacPherson et al. suggests that the reaction simply represents an adverse drug event, and there are no reasonable alternatives to the suspect drug, then the use of the drug could be justified after discussion with the patient. The risk, as always, is that the prescriber will have little recourse in the unfortunate situation should an untoward reaction occur. The label of ‘drug allergy’ needs to be applied with caution after the occurrence of an ADR. Patients should understand that unnecessarily labelling themselves as ‘allergic’ when it is not the case can result in the use of less appropriate medication in the future, as the ‘allergic’ label will restrict the prescriber’s choice. Even when the patient has suffered a true allergic reaction subsequent investigations may show that this was not caused by the drug thought to be responsible at the time.37 A second approach is the replacement on medication charts and anaesthetic record sheets of the work ‘drug allergy’ with ‘ADR’, which apart from being more correct terminology, might give prescribers more leeway in deciding whether to administer the stated drug or not after consideration of previous events. In our hospital, adverse drug events are recorded on a specific sheet, which is then transferred from the patient’s medical record to his or her medical admission notes during subsequent admissions. Therefore we have a permanent and ongoing record of previous adverse drug events recorded by appropriate and identifiable hospital personnel. We should also be aware that a large proportion, if not the majority, of ADRs occur in the community, and not the hospital setting.38 Appropriate communication of such events7 represents another possible area of improvement. Should an adverse drug event occur during the perioperative period the anaesthetist should make a point of discussing this with the patient. If it is likely that a Type A reaction has occurred the patient should be reassured that this does not constitute an allergic reaction and does not preclude the use of the drug in the future. The results of the present study indicate that in general anaesthetists take great care to avoid the administration of medications to which a patient has claimed a stated allergy. However, much of the information volunteered by patients is unreliable, reflecting events of decades earlier. Ensuring that patients are given accurate and preferably written details of adverse drug events that occur during their hospital admission will help alleviate these problems in the future. References 1 Shenfield GM, Robb T, Duguid M. Recording previous adverse drug reactions—a gap in the system. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2001; 51: 623–6 2 World Health Organisation. International drug monitoring: the role of the hospital. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser 1969; 425: 5–24 3 Rawlins MD, Thompson W. Mechanisms of adverse drug reactions. In: Davis DM, ed. Textbook of Drug Reactions. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1991; 18–45 638 4 Borda IT, Slone D, Jick H. Assessment of adverse reactions within a drug surveillance program. JAMA 1968; 205: 645–7 5 Gruchalla RS. Drug allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2003; 111: S548–59 6 Johansson SG, Hourihane JO, Bousquet J, et al. EAACI (the European Academy of Allergology and Cinical Immunology) nomenclature task force. A revised nomenclature for allergy. An EAACI position statement from the EAACI nomenclature task force. Allergy 2001; 56: 813–24 7 Johansson SG, Bieber T, Dahl R, et al. Revised nomenclature for allergy for global use: Report of the Nomenclature Review Committee of the World Allergy Organization, October 2003. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2004; 113: 832–6 8 Nebeker JR, Barach P, Samore MH. Clarifying adverse drug events: a clinician’s guide to terminology, documentation and reporting. Ann Intern Med 2004; 140: 795–801 9 Myers PS, Cheras PA. The other side of the coin: safety of complementary and alternative medicine. Med J Aust 2004; 181: 222–5 10 Peyriere H, Cassan S, Floutard E, et al. Adverse drug events associated with hospital admission. Ann Pharmacother 2003; 37: 5–11 11 Dormann H, Criegee-Rieck M, Neubert A, et al. Lack of awareness of community-acquired adverse drug reactions upon hospital admission: dimensions and consequences of a dilemma. Drug Saf 2003; 26: 353–62 12 Jones TA, Como JA. Assessment of medication errors that involved drug allergies at a university hospital. Pharmacotherapy 2003; 23: 855–60 13 deShazo RD, Kemp SF. Allergic reactions to drugs and biologic agents. JAMA 1997; 278: 1895–906 14 Hunziker T, Kunzi U, Braunschweig S, Zehnder D, Hoigne R. Comprehensive hospital drug monitoring: adverse drug reactions: a 20 year survey. Allergy 1997; 52: 388–93 15 Hung OR, Bands C, Laney G, Drover D, Stevens S, MacSween M. Drug allergies in the surgical population. Can J Anaesth 1994; 41: 1149–55 16 Thong BY, Leong K, Tang C, Chang H. Drug allergy in a general hospital: results of a novel prospective inpatient reporting system. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2003; 90: 342–7 17 Bigby M, Jick S, Jick H, Arndt K. Drug-induced cutaneous reactions; a report from the Boston Collaborative Drug Surveillance Program on 152,438 consecutive inpatients, 1975 to 1982. JAMA 1986; 256: 3358–63 18 Anderson JA. Allergic reactions to drugs and biologic agents. JAMA 1992; 268: 2845–57 19 Solensky R. Hypersensitivity reactions to beta-lactam antibiotics. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 2003; 24: 201–20 20 International Rheumatic Fever Group. Allergic reactions to longterm benzathine penicillin prophylaxis for rheumatic fever. Lancet 1991; 337: 1308–10 21 Joint Task Force on Practice Parameters, American Academy of Allergy Asthma and Immunology, American College of Allergy Asthma and Immunology, Joint Council of Allergy Asthma and Immunology. The diagnosis and management of anaphylaxis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1998; 101: S465–528 22 Neugut A, Ghatak A, Miller R. Anaphylaxis in the United States: an investigation into its epidemiology. Arch Intern Med 2001; 161: 15–21 23 Gadde J, Spence M, Wheeler B, Adkinson NF. Clinical experience with penicillin skin testing in a larger inner-city STD clinic. JAMA 1993; 270: 2456–63 24 Sullivan TJ, Wedner HJ, Schatz GS, Yecies LD, Parker CW. Skin testing to detect penicillin allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1981; 68: 171–80 Anaesthesia and drug allergies 25 Choi IS, Koh YI, Koh JS, Lee MG. Sensitivity of the skin prick test and specificity of the serum-specific IgE test for the airway responsiveness to house dust mites in asthma. J Asthma 2005; 42: 197–202 26 Golden DB, Tracy JM, Freeman TM, Hoffman DR. Negative venom skin test results in patients with histories of systemic reaction to a sting. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2003; 112: 495–8 27 Moneret-Vautrin DA, Kanny G. Anaphylaxis to muscle relaxants: rationale for skin tests. Allerg Immunol 2002; 34: 233–40 28 Saxon A, Beall GN, Rohr AS, Adelman DC. Immediate hypersensitivity reactions to beta-lactam antibiotics. Arch Intern Med 1987; 107: 204–15 29 Anne S, Reisman RE. Risk of administering cephalosporin antibiotics to patients with histories of penicillin allergy. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 1995; 74: 167–70 30 Strom BL, Schinnar R, Apter AJ, et al. Absence of cross-reactivity between sulfonamide antibiotics and sulfonamide nonantibiotics. N Eng J Med 2003; 349: 1628–35 639 31 Gruchalla RS. Understanding drug allergies. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2000; 105: S637–44 32 McMahon AD, Evans JM, MacDonald TM. Hypersensitivity reactions associated with exposure to naproxen and ibuprofen: a cohort study. J Clin Epidemiol 2001; 54: 1271–4 33 Greenberg GN. Recurrent sulindac-induced aseptic meningitis in a patient tolerant to other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. South Med J 1998; 81: 1463–4 34 Webber JC, Eissigman WK. Pulmonary alveolitis and NSAIDs fact or fiction? Br J Rheumatol 1986; 25: 5–6 35 Molloy A. Does pethidine still have a place in therapy? Aust Prescr 2002; 25: 12–13 36 Butani L. Corticosteroid-induced hypersensitivity reactions. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2002; 89: 439–45 37 Kroigaard M, Garvey LH, Menne T, Husum B. Allergic reactions in anaesthesia: are suspected causes confirmed on subsequent testing? Br J Anaesth 2005; 95: 468–71 38 Incidence of serious adverse drugs reactions in general practice: a prospective study. Clin Pharm Ther 2001; 69: 458–62