* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

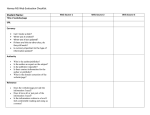

Download WHO Safe Childbirth Checklist Implementation Guide

Infection control wikipedia , lookup

Breastfeeding wikipedia , lookup

HIV and pregnancy wikipedia , lookup

Neonatal intensive care unit wikipedia , lookup

Birth control wikipedia , lookup

Reproductive health wikipedia , lookup

Prenatal nutrition wikipedia , lookup

Maternal health wikipedia , lookup

Breech birth wikipedia , lookup

Fetal origins hypothesis wikipedia , lookup