* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Diagnosis

Public health genomics wikipedia , lookup

Transmission (medicine) wikipedia , lookup

Self-experimentation in medicine wikipedia , lookup

Hygiene hypothesis wikipedia , lookup

Non-specific effect of vaccines wikipedia , lookup

Infection control wikipedia , lookup

Compartmental models in epidemiology wikipedia , lookup

Canine parvovirus wikipedia , lookup

Marburg virus disease wikipedia , lookup

Epidemiology of measles wikipedia , lookup

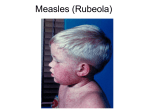

„Approved” on methodical conference department of infectious diseases and epidemiology „____” ____________ 200 р. Protocol № _____ Chief of Dept., professor __________ V.D. Moskaliuk METHODOLOGICAL INSTRUCTIONS to a fifth year student of the Faculty of Medicine on independent preparation for practical training Topic: MEASLES, MUMPS, SMALLPOX IN ADULT, MORBILLI VIRUS, SCARLET FEVER Subject: Major: Educational degree and qualification degree: Year of study: Hours: Prepared by Infectious Diseases Medicine Specialist 5 2 Sorokhan MD, PhD. Topic: Measles, mumps, smallpox in adult, scarlet fever. 1. Lesson duration: 2 hours 2. Aims of the lesson: 3.1. Students are to know: • etiology of measles, mumps, smallpox and scarlet fever; • epidemiology of measles, mumps, smallpox and scarlet fever; • pathogenesis of measles, mumps, smallpox and scarlet fever; • symptoms and development of measles, mumps, smallpox and scarlet fever; • measles, mumps, smallpox, scarlet fever complications; • diagnosis of measles, mumps, smallpox and scarlet fever; • differential diagnosis of measles, mumps, smallpox and scarlet fever; • treatment of measles, mumps, smallpox and scarlet fever; • prophylactic and antiepidemic measures at measles, mumps, smallpox and scarlet fever. 3.2. Students are to be able: • to question a patient in order for obtaining of information on disease history and epidemiologic anamnesis; • to perform clinical examination of a patient; • to formulate and to substantiate the diagnosis of measles, mumps, smallpox and scarlet fever; • to prepare a plan of additional patient examination; • to make differential diagnosis of measles, mumps, smallpox and scarlet fever; • to prescribe adequate etiotropic treatment; • to prepare a plan and organize prophylactic and antiepidemic measures. 3.3. Students are to acquire the following skills: • to conduct clinical examination of patient with measles, mumps, smallpox and scarlet fever; • to formulate and substantiate a clinical diagnosis; • to prepare a plan of paraclinic patient examination; • to evaluate results of paraclinic patient examination; • to organize hospitalization and treatment of patients with measles, mumps, smallpox and scarlet fever; • to plan and organize prophylactic measures against measles, mumps, smallpox and scarlet fever; • to plan and organize antiepidemic measures to localize and liquidate a measles, mumps, smallpox and scarlet fever; 4. Advice to students. MEASLES (RUBEOLA) Measles (rubeola) is an acute highly contagious disease, caused by a virus, featuring fever, runny nose, cough, red eyes, and a spreading skin rash. Rubeola is measles. The name "measles" comes from the Middle English "maselen" meaning "many little spots" referring to the rash that is characteristic of measles. Rubeola refers specifically to the reddish color of the rash. Other names for the measles (rubeola) include the hard measles and (depending on how long you think it lasts) the seven-day measles, the eight-day measles, the nine-day measles, or the ten-day measles, and morbilli. Etiology Measles is caused by paramyxovirus. Epidemiology The measles virus is, in fact, spread principally by small droplets from the nose, throat, and mouth of someone who is in the early stages of the disease. These infected droplets are sprayed out during sneezing and coughing. Measles can also be passed by direct contact with nasal or throat secretions of infected persons or objects contaminated with the measles virus. Measles is among the most readily transmitted of all infectious diseases. Measles epidemics occur every 23 years in areas of the world without effective immunization programs and there are small localized outbreaks in the intervening years. These outbreaks are often in unimmunized preschoolers or other unimmunized people in the population. A child born to a mother who had measles receives immunity from its mother lasting most of the first year of life. One attack of measles provides lifelong immunity, and proper vaccination confers lifelong protection against measles. The incubation period is 7-14 days. A person with measles can transmit it beginning 2 to 4 days before the rash appears until the time that the rash fades and clears. Symptoms Typical measles begins with fever, runny nose (coryza), hacking cough, and red eyes (conjunctivitis). The very characteristic (pathognomonic) spots within the mouth (called Koplik's spots) appear 2 to 4 days later, are often on the inside of the cheeks (the buccal mucosa) opposite the 1st and 2nd upper molars, and look like little grains of white sand surrounded by a red ring. Sore throat (pharyngitis) occurs along with inflammation of the airways (the laryngeal and tracheobronchial mucosa) develop. The rash appears 3 to 5 days after the onset of symptoms. The rash progresses from the head downward. It begins below the ears and on the side of the neck as small irregular bumps that soon increase in size and spread rapidly (within 1-2 days) to the trunk and limbs as they begin to fade on the face. Bleeding spots (petechiae) and bruises (ecchymoses) can occur with very severe rashes. The fever can top 104° F (40° C). The eyes are reddened and watery (conjuctivitis), very sensitive to light (photophobiac) and there is swelling around the orbits (periorbital edema). There is a hacking cough. The patient looks (and feels) sick. The course of the disease usually follows the course of the rash. In 3 to 5 days, the rash begins to fade, the fever falls abruptly, and the patient feels more comfortable. (The patient now can no longer pass on the disease). The rash may leave discoloration in its wake and the discolored skin may peel. The atypical measles syndrome (AMS) is an altered expression of measles. AMS begins suddenly with high fever, headache, cough, and abdominal pain. The rash may appear 1 to 2 days later, often beginning on the limbs. Swelling (edema) of the hands and feet may occur. Pneumonia is common and may persist for 3 months or more. Diagnosis The diagnosis of measles may be suspected in someone with a head cold, light sensitivity of the eyes (photophobia) and bronchitis. But before the rash appears, a definitive diagnosis of measles can be made only by seeing Koplik's spots, the tiny white spots most often seen on the inside of the cheeks (the buccal mucosa) opposite the lst and 2nd upper molars. These spots, followed by high fever and the rash with its characteristic progression firmly establish the clinical diagnosis of measles. The measles virus can be detected in the early stage of the disease. This is done by rapid staining (by immunofluorescence) of cells from the throat (pharynx) or urine. The virus can be isolated in tissue culture in the lab. Blood (serologic) tests are also available. Isolation of the measles virus by growing it in tissue culture and/or blood (serologic) tests may be necessary to establish the diagnosis of the atypical measles syndrome (AMS) because AMS, by definition, involves the altered expression of the disease (modified measles). Differential diagnosis It might be a lot of other diseases including rubella (German measles), scarlet fever, drug rashes, roseola, infectious mononucleosis, and adenovirus, echovirus and coxsackievirus infections. Atypical measles syndrome (AMS) can be confused with other diseases including Rocky Mountain spotted fever, meningococcal infection, various types of pneumonia, appendicitis, juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, and others. Complications A number of different types of complications, some of them very serious, even fatal, can and do occur with measles: Bacterial infections: Pneumonia and ear infections (otitis media), and other bacterial infections are common complications. People with measles are vulnerable to strep infections. Measles can reactivate and worsen tuberculosis (TB). Immune deficiency: Immunodeficient patients may develop a grave progressive pneumonia without a rash. Acute thrombocytopenic purpura: Low blood platelet levels (important blood clotting elements) with severe bleeding constitute a potentially serious complication during the acute phase of measles. Encephalitis: Brain inflammation (encephalitis) occurs in 1 in 1,000 cases. It starts (up to 3 weeks) after onset of the rash and presents with high fever, convulsions, and coma. It may run a blessedly short course with full recovery within a week. Or it may eventuate in central nervous system impairment or death. Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE): The measles virus causes subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE), a chronic brain disease of children and adolescents that occurs months to often years after an attack of measles, causing convulsions, motor abnormalities, mental retardation and, usually, death. Treatment Eye care: The eyes may be very sensitive to light and have an irritating discharge. Wash the eyes by wiping them with a clean, wet washcloth but avoid rubbing them. Keep lights dim or the room darkened. Sunglasses may also help. Humidity: For the cough, humidify the air with a cool mist vaporizer or with pans of water set in the room. The mist from a shower also helps. Fluids: Increase fluids to 12-16 glasses of liquid (8 ounces or 250 ml per glass) a day during the fever. You should drink enough fluids to cause urination every 2 hours. Bed rest: Stay in bed during the fever. Balanced diet: Eat a balanced diet (as always, we hope). Avoid aspirin: Avoid aspirin and all aspirin products. (Aspirin today is not recommended for children or for patients with infectious diseases caused by viruses, because of the association with Reyes syndrome). Prognosis Barring complications, measles has a low mortality rate when it occurs in normal wellnourished healthy children. Unfortunately, complications are not rare with measles and they increase the degree of morbidity (illness). And some of the complications of measles (such as measles encephalitis and subacute sclerosing panencephalitis) carry an appreciable mortality rate. Prevention The way to prevent measles is by measles immunization: The standard MMR (measles, mumps and rubella) vaccine is given in two dosages. The first dose should be at 12-15 months of age. The second vaccination should be at 4-6 years of age. Measles, mumps, and rubella vaccines may be administered as individual shots, if necessary, or as a measles-rubella combination. Most children should receive MMR vaccinations. Exceptions may include children with congenital immunodeficiency (born with an inability to fight off infection), some children on treatment with radiation or drugs for cancer, and children on long term steroids (cortisone). People with severe allergic reactions to eggs or the drug neomycin should probably avoid the MMR vaccine. Pregnant women should wait until after delivery before being immunized with MMR. Worldwide (universal) immunization against measles is the goal. Exceptions should be made only for special reasons. People with HIV or AIDS should normally receive MMR vaccine. MUMPS Mumps is a contagious viral infection that can cause painful swelling of the parotid glands, which are the salivary glands located between the ear and the jaw. Epidemiology Mumps is spread when an infected person coughs or sneezes, as well as through contact with contaminated items such as tissues, drinking glasses, and dirty hands. The incubation period is usually 16 to 18 days, although it can be as long as 4 weeks. Usually, infected people are contagious a day or two before the first symptoms appear, although they can spread the virus any time from 7 days before to 9 days after symptoms appear. Symptoms Mumps can affect many body systems and cause flu-like symptoms, abdominal pain, swollen cheeks, and swollen and painful testicles. However, up to 20% of people who are infected with the mumps virus do not have any symptoms. The mumps virus enters your body through the nose and throat. You may start to feel symptoms as the virus multiplies and spreads to the brain and the membranes that cover it, glands (usually the salivary glands), pancreas, testicles, ovaries, and other areas of the body. Symptoms usually last about 10 days and may include: Swelling and pain in one or both parotid glands, which are the salivary glands located between the ear and jaw. One or both cheeks may look swollen. About 30% to 40% of people infected with mumps have this symptom. 1 Many people consider swollen parotid glands to be a classic sign of mumps, however, this symptom can also develop with other conditions. Fever of 101° (38°) to 104° (40°). Headache, earache, sore throat, and pain when swallowing or opening the mouth. Pain when eating sour foods or drinking sour liquids, such as citrus fruit or juice. Tiredness, with aching in the muscles and joints. Poor appetite and vomiting. Some people who are infected with the mumps virus do not have any symptoms. Diagnosis Mumps is most often diagnosed by a history of exposure to the disease, the presence of swelling and tenderness of the parotid glands, and other symptoms, including neck stiffness, headache, and painful testicles. If needed, blood tests, such as an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA, EIA), can be done to confirm the diagnosis and eliminate the possibility that another illness is causing the symptoms. The mumps virus itself can be identified with a viral culture of samples of urine, saliva, or cerebrospinal fluid obtained by a lumbar puncture. Differential diagnosis In the past, smallpox was sometimes confused with chickenpox, a childhood infection that's seldom deadly. Yet chickenpox differs from smallpox in several important ways: Severity and location of lesions. Chickenpox lesions are much more superficial than are those of smallpox and occur primarily on the trunk, rather than on the face, arms and hands. Types of lesions. You'll often see a combination of scabs, vesicles and pustules in someone with chickenpox. In smallpox, all of the lesions in a given area are at the same stage. Timing of transmission. A person infected with chickenpox can unknowingly transmit the virus to others before symptoms ever develop. But smallpox becomes infectious only when signs and symptoms appear and remains contagious until scabs fall from the pustules. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), smallpox is most contagious after the fever starts and during the first week of the rash. You're less likely to become infected if you're exposed to someone in the later stages of the disease. Complications Complications may require treatment in the hospital. Medications to relieve pain associated with orchitis, meningitis, pancreatitis, and other complications may be given. Treatment with other medications, such as interferon for severe orchitis, is experimental. Antibiotics are not given to treat mumps or other viral infections. Treatment In most cases, people recover from mumps with rest and care at home. In complicated cases, hospitalization may be required. Prevention Mumps can almost always be prevented by getting a series of injections with the combination measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine. The first MMR injection usually is given around 12 to 15 months of age. Most babies do not become infected with mumps during their first year of life because of the temporary immunity they acquired during fetal development. SMALLPOX Smallpox is a contagious, disfiguring and often deadly disease caused by the variola virus. It's believed to have first appeared in northeastern Africa or south-central Asia nearly 12,000 years ago. Since then, few other illnesses have had such a profound effect on human health and history. In the 20th century alone, an estimated 300 million people died of smallpox. The initial signs and symptoms of smallpox, which appear about two weeks after infection, resemble those of the flu: fever, fatigue and headache. Later, severe pus-filled blisters appear on the skin that eventually leave deep, pitted scars. Once symptoms develop, there's no effective treatment for smallpox and no known cure. Naturally occurring smallpox was finally eradicated worldwide in the 1970s - the result of an unprecedented immunization campaign. But the virus didn't disappear entirely. Stocks of smallpox virus, set aside for research purposes, are officially stored in two high-security labs - one in the United States and one in Siberia. This has lead to concerns that smallpox someday may be used as a biological warfare agent. Etiology The variola virus causes smallpox. Under high magnification, variola particles look like rectangles with a deeply patterned surface. They're sometimes referred to as bricks. Each brick is composed of at least a hundred different proteins. Although extraordinarily large for a virus, 3 million smallpox bricks lined end to end would be no larger than the period at the end of a sentence. Once you're infected, the virus immediately begins replicating inside your cells - first in the lymph nodes and then in your spleen and bone marrow. Eventually, the virus settles in the blood vessels in your skin and the mucous membranes of your nose and throat. When the lesions in your mouth slough off, large amounts of virus are released into your saliva. This is when you're most likely to transmit the disease to others. Epidemiology Smallpox usually requires face-to-face contact to spread. It's most often transmitted in air droplets when an infected person coughs, sneezes or talks. Inhaling a single particle may be enough to cause infection. In rare instances, airborne particles may spread through the ventilation system in a building, infecting people in other rooms or on other floors. Smallpox also can spread through contact with contaminated clothing and bedding, although the risk of infection from these sources is slight. Smallpox outbreaks typically occur in two-week intervals. Initially, just a few people get sick. Fourteen days later, a larger number of people develop the disease, and in another two weeks, even more cases appear. This pattern reflects the incubation period of the virus as well as its exponential spread. There are two main forms of smallpox exist: Variola minor. This is a milder form of the disease and causes a less serious illness. It's fatal in less than 1 percent of people who contract it. Variola major. By contrast, this form of the disease kills one-third of the people it infects. There are also two rare forms of smallpox: Hemorrhagic smallpox. This form is characterized by a red, pinpoint rash and bleeding in the skin and mucous membranes. In some cases, hemorrhagic smallpox may destroy the entire skin surface and all mucous membranes. Hemorrhagic smallpox is almost always fatal within five to seven days. Malignant smallpox. This form is also often fatal. The early signs and symptoms are similar to other forms of the disease, but the lesions are velvety and never become filled with pus. Eventually, the skin takes on a rubbery appearance. Bleeding in the skin and intestinal tract also may occur. Symptoms The first symptoms of smallpox usually appear 12 to14 days after you're infected. During the incubation period of seven to 17 days, you look and feel healthy and can't infect others. Following the incubation period, a sudden onset of flu-like signs and symptoms occurs. These include: Fever A feeling of bodily discomfort (malaise) Headache Severe fatigue (prostration) Severe back pain A few days later, the characteristic smallpox rash appears as flat, red spots (lesions). Within a day or two, many of these lesions turn into small blisters filled with clear fluid (vesicles) and later, with pus (pustules). The rash appears first on your face, hands and forearms and later on the trunk. It's usually most noticeable on the palms of your hands and the soles of your feet. Lesions also develop in the mucous membranes of your nose and mouth. The way the lesions are distributed is a hallmark of smallpox and a primary way of diagnosing the disease. When the pustules erupt, the skin doesn't break, but actually separates from its underlying layers. The pain can be excruciating. Scabs begin to form eight to nine days later and eventually fall off, leaving deep, pitted scars. All lesions in a given area progress at the same rate through these stages. People who don't recover usually die during the second week of illness. Diagnosis Trained health workers can diagnose smallpox without the need for laboratory tests. The World Health Organization provides training materials to help health staff recognize smallpox and distinguish it from chickenpox. Still, an initial case of smallpox is likely to be confirmed by laboratory testing. Even a single confirmed case of smallpox would be considered an international health emergency to be reported immediately to local health authorities and national officials. Differential diagnosis In the past, smallpox was sometimes confused with chickenpox, a childhood infection that's seldom deadly. Yet chickenpox differs from smallpox in several important ways: Severity and location of lesions. Chickenpox lesions are much more superficial than are those of smallpox and occur primarily on the trunk, rather than on the face, arms and hands. Types of lesions. You'll often see a combination of scabs, vesicles and pustules in someone with chickenpox. In smallpox, all of the lesions in a given area are at the same stage. Timing of transmission. A person infected with chickenpox can unknowingly transmit the virus to others before symptoms ever develop. But smallpox becomes infectious only when signs and symptoms appear and remains contagious until scabs fall from the pustules. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), smallpox is most contagious after the fever starts and during the first week of the rash. You're less likely to become infected if you're exposed to someone in the later stages of the disease. Complications Historically, variola major is fatal in about 30 percent of people who contract it. Almost no one survives the hemorrhagic and malignant forms of the disease. People who recover from smallpox usually have severe scars, especially on the face, arms and legs. In many cases, smallpox may lead to blindness. Treatment No cure for smallpox exists. There is some evidence that cidofovir - an antiviral medication normally used to treat an infection known as cytomegalovirus (CMV) - might prevent smallpox if it's administered within a day or two of exposure. The smallpox vaccine itself can prevent or lessen the severity of the disease if given within four days of infection. But neither of these is useful once signs and symptoms develop, and both can have serious side effects. For now, the best that doctors can offer people with symptomatic smallpox is supportive therapy and antibiotics to prevent secondary infections. Apart from immediate vaccination, isolation is the only way to manage the disease. Unfortunately, isolation can only contain the spread of the virus, not eradicate it. If an outbreak of smallpox were to occur, people with confirmed cases of the disease would be treated in separate hospitals, in other special facilities or at home. Those admitted to regular hospitals would probably be placed in negative pressure rooms - the pressure outside the room is greater than the pressure inside - with highly sophisticated air filtration systems. Strict precautions would be taken with bed linen and clothing. Even so, the risk is so high that all hospital employees as well as most other patients would probably be vaccinated against the disease. Prevention Smallpox is one of the most devastating of human diseases. In its 12,000-year history, it has probably killed more people than any other illness, including the plague. Yet no naturally occurring smallpox cases have been reported for nearly 25 years. The story of smallpox prevention, and its eventual eradication through immunization, is a long and compelling one. For centuries, it was known that people who survived smallpox became immune to it. For that reason, nearly every civilization tried to induce immunity in healthy individuals. The Chinese used tubes to insert powdered smallpox scabs into their nostrils. In Turkey, pus from lesions was scratched into the skin. Eventually these methods - collectively known as variolation reached Europe and the New World. There, as elsewhere, variolation had varying degrees of success. Some people became immune, but others contracted the disease and died or became the source of a new epidemic. Still, by the early 1700s, "do-it-yourself" smallpox inoculation had become widespread. In 1788, the scientist Edward Jenner inoculated a healthy, 8-year-old boy with cowpox - a disease caused by a virus that closely resembles variola. Cowpox's natural hosts are small mammals such as wood mice, but the virus can spread to other animals, especially cattle, and lesions on the udders and teats of cows can infect people who milk them. Although rare today, cowpox was widespread in 18th-century Europe, where it was common knowledge that milkmaids who had been infected with cowpox - which is generally mild were then immune to the far more deadly smallpox. Jenner's experiment was a success. His patient failed to contract smallpox, even when deliberately exposed to variola. By 1800, cowpox vaccinations (the word "vaccine" is from the Latin word for "cow") were commonplace, primarily because they caused fewer side effects and deaths than did variolation with smallpox itself. Smallpox vaccine that was used in the United States until vaccinations were stopped contained live vaccinia virus - a virus similar to cowpox and closely related to variola. Before 1972, most young children were vaccinated against smallpox, as were military recruits and many people traveling out of the country. In 1967, the World Health Organization launched a global immunization campaign to eradicate smallpox. At that time, 2 million to 3 million people died of smallpox every year. The WHO's efforts were remarkably effective, and the last naturally occurring case of smallpox was reported in 1977. In 1980, smallpox vaccinations were discontinued worldwide. SCARLET FEVER Scarlet fever, or scarlatina, is an illness that brings on a rash covering most of the body, a strawberry-like appearance of the tongue and usually a high fever. The most common source of scarlet fever is one form of a common bacterial infection known as strep throat. Therefore, a sore throat and other signs and symptoms of a typical strep throat infection almost always accompany scarlet fever. Infrequent sources of scarlet fever are related bacterial infections affecting other organ systems. Scarlet fever rarely affects people older than 18 and is most common in children 5 to 15 years of age. Although scarlet fever was once considered a serious childhood illness, antibiotic treatments have made it less threatening. Nonetheless, if left untreated, scarlet fever (like strep throat) can result in more serious conditions that affect the heart, kidneys and other parts of the body. Etiology A bacterium called Streptococcus pyogenes, or group A beta-hemolytic streptococcus causes scarlet fever. This is the same bacterial infection that causes strep throat, but the strain of bacteria causing scarlet fever releases toxins that produce the rash, Pastia's lines, flushed face and red tongue. Epidemiology. Strep bacteria that cause scarlet fever spread from one person to another by fluids from the mouth and nose. If an infected person coughs or sneezes, the bacteria can become airborne, or the bacteria may be present on things the person touches — a drinking glass or a doorknob. If you're in proximity to an infected person, you may inhale airborne bacteria. If you touch something an infected person has touched and then touch your own nose or mouth, you could pick up the bacteria. The incubation period is usually two to four days. If scarlet fever isn't treated, a person may be contagious for a few weeks even after the illness itself has passed. And someone may carry scarlet fever strep bacteria without being sick. Therefore, it's difficult to know if you've been exposed. Scarlet fever strep bacteria can also contaminate food, especially milk, but this mode of transmission isn't as common. Rare causes of scarlet fever are other strains of Streptococcus pyogenes associated with either a skin infection (impetigo) or a uterine infection contracted during childbirth. These cases result in the characteristic fever, rash and other "scarlet" symptoms but not signs and symptoms associated with a throat infection. Symptoms Red rash that looks like a sunburn and feels like sandpaper Red lines (Pastia's lines) in folds of skin around the groin, armpits, elbows, knees and neck Strawberry-like red and bumpy appearance of the tongue, often covered with a white coating early in the disease Flushed face with paleness around the mouth Fever of 101 degrees Fahrenheit or higher, often with chills Very sore and red throat, sometimes with white or yellowish patches Difficulty swallowing Enlarged glands in the neck (lymph nodes) that are tender to the touch Nausea or vomiting Headache The sore throat, enlarged lymph nodes and fever are likely to appear first, while the "scarlet" signs and symptoms of scarlet fever usually appear on the second day of illness. If your child has scarlet fever, the rash will most likely begin on his or her chest and spread to the neck, trunk, arms and legs. The rash won't appear on your child's face, palms of the hands or soles of the feet. The rash and the redness in the face and tongue usually last about a week. After these scarlet fever symptoms have subsided, the skin affected by the rash often peels. The red rash of scarlet fever usually begins on the chest and spreads to the neck, trunk, arms and legs. Diagnosis The diagnosis is made by throat culture. The sample from your child's throat is examined in a laboratory test in which the bacteria can thrive. Although this is a very reliable test, the results may take as long as two days. Rapid antigen test. Your doctor may also order a rapid antigen test, sometimes called a rapid strep test, which can detect foreign proteins (antigens) associated with strep bacteria infection. This test can be completed during a visit to your doctor's office. This test is less reliable than a throat culture. If a rapid antigen test is negative, your doctor will probably order the throat culture to ensure an accurate diagnosis. Rapid DNA test. Your doctor may also be able to order a relatively new rapid test that uses DNA technology to detect strep bacteria from a throat swab in a day or less. These tests are at least as accurate as throat cultures, and the results are available sooner. Complications Scarlet fever rarely results in serious complications, particularly if promptly and appropriately treated with antibiotics. But post-scarlet fever disorders may occur. These include: Rheumatic fever. Rheumatic fever is an inflammatory disease that can affect the heart, joints, skin and nervous system. Long-term effects may include damage to heart valves; other heart disorders; and a syndrome called Sydenham's chorea, which causes emotional instability, muscle weakness and jerky movements of the hands, feet and face. Appropriate treatment of strep bacteria infection greatly reduces the risk of rheumatic fever. Poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis. Poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis is inflammation of the kidneys that results from certain byproducts of strep bacteria infection. This disorder may cause long-term kidney disease. Pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections (PANDAS). In children who have neuropsychiatric disorders, such as obsessivecompulsive disorder and Tourette syndrome, some researchers believe strep bacteria infection may cause or are associated with an autoimmune disorder that significantly exacerbates psychiatric symptoms. Other complications that may result from untreated scarlet fever include: Bacterial infection of the blood (bacteremia) Ear infection (otitis media) Inflammation of the membranes and fluid that surround the brain and spinal cord (meningitis) Infection of the bone behind the ear (mastoiditis) Infection of the heart's inner lining (endocarditis) Pneumonia Inflammation of mucous membranes and buildup of fluids in the sinuses (sinusitis Arthritis Pus-filled sac (abscess) in the throat Skin infections Treatment An antibiotic medication include: Penicillin, in pill form or by injection Amoxicillin (Amoxil, Trimox) Azithromycin (Zithromax) Clarithromycin (Biaxin) Clindamycin (Cleocin) A cephalosporin (Keflex, Ceclor) Prevention The best prevention strategies for scarlet fever are the same as the standard precautions against infections: Wash your hands. Don't share dining utensils. Cover your mouth and nose. 5. Test questions. 1. What is measles? 2. What is rubeola? 3. What causes measles (rubeola)? 4. How is measles spread? 5. How does one become immune to measles? 6. What is the incubation period for measles infection? 7. When is measles communicable? 8. What are signs and symptoms of measles? 9. What is the atypical measles syndrome (AMS)? 10. How is the diagnosis of measles made? 11. What laboratory testing can assist the diagnosis? 12. How is the lab diagnosis of the atypical measles syndrome made? 13. If it isn't measles, what might it be? 14. What complications can occur with measles? 15. What to do if someone is exposed to measles? 16. What can your health care provider do to treat the measles? 17. What can I do to treat the measles? 18. What is the outlook (prognosis) with measles? 19. How can measles be prevented? 20. What is mumps? 21. What causes mumps? 22. What are the symptoms? 23. How is mumps diagnosed? 24. How is it treated? 25. Can mumps be prevented? 26. What are signs and symptoms of mumps? 27. What testing can assist the diagnosis? 28. How can mumps be prevented? 29. What is smallpox? 30. What causes smallpox? 31. What are the symptoms? 32. How is smallpox diagnosed? 33. What are signs and symptoms of smallpox? 34. What is scarlet fever? 35. What causes scarlet fever? 36. What are the symptoms? 37. How is scarlet fever diagnosed? 38. How is it treated? 39. What are signs and symptoms of scarlet fever? 40. What testing can assist the diagnosis? 6. Literature: 1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2001). Mumps. Health Topics A to Z. Available online: http://www.cdc.gov/nip/publications/pink/mumps.pdf. 2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2004). Summary of notifiable diseases, United States, 2002. MMWR, 51(53): 1–84. 3. Madsen KM, et al. (2002). A population-based study of measles, mumps, and rubella vaccination and autism. New England Journal of Medicine, 347(19): 1477–1482. 4. American Academy of Pediatrics (2003). Mumps. In LK Pickering, ed., Red Book: 2003 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases, 26th ed., pp. 439–443. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics. 5. Sydney Youngerman-Cole, RN, BSN, RNC Medical Review: Adam Husney, MD - Family Medicine.