* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Progressive Multifocal Leukoencephalopathy

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

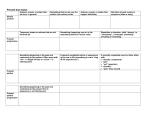

Review Article Address correspondence to Dr Allen J. Aksamit Jr, Mayo Clinic, Department of Neurology, 200 First Street SW, Rochester, MN 55905, [email protected]. Relationship Disclosure: Dr Aksamit reports no disclosure. Unlabeled Use of Products/Investigational Use Disclosure: Since there are no US Food and Drug Administration approved treatments for progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, all treatments discussed by Dr Aksamit are unlabeled. * 2012, American Academy of Neurology. Progressive Multifocal Leukoencephalopathy Allen J. Aksamit Jr, MD, FAAN ABSTRACT Purpose of Review: Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) is an opportunistic viral infection of the human CNS that has gained new importance because of AIDS and newer immunosuppressive therapies. It destroys oligodendrocytes, leading to neurologic deficits associated with demyelination. Recent Findings: PML most commonly occurs in patients who are HIV infected, but increasing numbers of patients are being recognized in the context of immunosuppressive therapies for autoimmune diseases. The precise pathogenesis of infection by JC virus, the etiologic human papovavirus, remains elusive, but much has been learned since the original description of the pathologic entity PML in 1958. Detection and diagnosis of this disorder have become more sophisticated with MRI of the brain and spinal fluid analysis using PCR detection. Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome complicates reversal of immunosuppression when PML has established a foothold in the brain. Summary: No effective therapy exists, but there is hope for better management of patients by withdrawing exogenous immunosuppression and reconstituting the immune system, with a projection of better long-term survival. Continuum Lifelong Learning Neurol 2012;18(6):1374–1391. INTRODUCTION Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) is caused by JC virus infection of the oligodendrocytes in the white matter of the brain, which leads to neurologic deficits. JC virusYinduced killing of oligodendrocytes leads to myelin loss focally. This is manifest as dysfunction of the cerebral hemispheres, cerebellum, or brainstem. The optic nerves and spinal cord are not clinically affected in PML. This helps to distinguish it from multiple sclerosis (MS). JC virusYinduced PML is regarded as an opportunistic infection of the human nervous system. AIDS is the most common associated immunocompromising illness in recent years, but non-AIDS immunosuppressive illnesses also cause PML. In past years, lymphoretic- 1374 www.aan.com/continuum ular malignancy, such as chronic lymphocytic leukemia or non-Hodgkin lymphoma, have caused PML. These are considered B-cell neoplasms. The importance of B cells in PML pathogenesis is not yet fully understood, but some researchers have suggested B cells carry JC virus into the brain. Other diseases associated with immunosuppression, such as those related to organ transplantation, and immunosuppression associated with rheumatoid arthritis, sarcoidosis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and dermatomyositis, have all caused PML. It is unclear whether these disorders intrinsically lead to immunosuppression causing PML or whether the treatments are required for PML to occur. Immunosuppression prolonged for 6 months or more is associated with PML. December 2012 Copyright @ American Academy of Neurology. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited. HISTORY PML, first described as a neuropathologic entity in 1958,1 was noted to be a microscopically multifocal demyelinating disease, with coalescence-forming macroscopic lesions. Histologically, oligodendrocyte nuclear enlargement and bizarre astrocyte formation established the disease as unique. Early on, it was suspected to be a viral illness, based on the pathologic appearance of the inclusion-bearing oligodendrocytes and its occurrence in immunosuppressed populations.2 At the advent of electron microscopic investigation, electron micrographs revealed polyomavirusYsize particles in the nuclei of the infected oligodendrocytes.3 However, it took until 1971, when brain from a patient with PML was cultured with human fetal glial cells by Padgett and colleagues,4 to isolate a replicating human DNA polyomavirus. The patient’s name from whom this virus was identified was John Cunningham, leading to the designation as JC virus. Within 2 years, the group at Wisconsin did further investigations to show that much of the population carried antibodies to the newly described JC virus.5 Early on, it was shown that the virus exposure occurred as a consequence of adolescent or early adulthood exposure, and persistent serologic reactivity was present in 60% to 70% of the population. Other researchers isolated another polyomavirus, called SV40 virus, from another PML patient,6 but all subsequent PML cases studied by molecular means have been caused by JC virus. Part of the unique PML histopathology was the finding of bizarre astrocytes. These are cytologically bizarre and have the appearance of tumorlike astrocytic cells. A case of glioma in a human PML patient was reported as early as 1974.7 Subsequently, however, gliomas have been extraordinarily rare, and controversy about the association Continuum Lifelong Learning Neurol 2012;18(6):1374–1391 between the JC virus and human glioma remains.8Y10 By 1982, PML was reported to be associated with AIDS.11,12 A review in 1984 showed only a few hundred cases of known PML, some of which were from the early aspects of the AIDS epidemic, although most had been associated with other immunosuppressive illness.13 By 1984, the complete nucleotide sequence of the double-stranded DNA JC virus was published.14 It was found to be closely linked to the SV40 virus and another human polyomavirus, designated BK virus. By 1985, nonradioactive means of in situ hybridization provided evidence that oligodendrocytes and bizarre astrocytes in the brain of patients with PML were infected by JC virus.15 These tools became useful for confirming the presence of JC virus in cases of PML requiring pathologic confirmation by brain biopsy. Immunohistochemical staining for JC virus antigen has also provided means for pathologic confirmation of this infection.16 Although the pathogenesis of JC virus entry into the brain remains somewhat unclear, in 1988 B cells were reported to contain JC virus in patients with PML.17 Other authors subsequently showed that JC virus was detected in lymphocytes of PML and HIV-positive patients by PCR.18 The PCR revolution in virology affected the diagnosis of PML. For the first time, in 1992, JC virus was detected in the spinal fluid of patients with PML.19,20 This has become the noninvasive standard for diagnosing PML and has now become accepted as a surrogate marker for histologic proof of JC virus replication in the brain.21 Despite the severe and usually fatal nature of PML, no proven therapy has been defined. A landmark article testing cytarabine in AIDS-related PML was published and found to be ineffective KEY POINT h Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy is a reactivation, opportunistic infection by JC virus. www.aan.com/continuum Copyright @ American Academy of Neurology. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited. 1375 Progressive Multifocal Leukoencephalopathy KEY POINT h Most people (50% to 70%) are latently infected with JC virus. in patients with AIDS.22 A variety of agents have been tried, but none with any reliable success. More recently, PML has occurred in patients with MS treated with natalizumab, an immunomodulatory monoclonal antibody. Natalizumab was removed from the United States drug market for a time because of its association with PML infection23Y25 but later returned to the market under stricter prescribing guidelines.26 This, however, became a harbinger of PML occurring with other commonly used immunosuppressive agents, including rituximab and mycophenolate mofetil.26,27 It is anticipated that additional immunosuppressive therapies may likewise continue to predispose to PML as an opportunistic infection. In opportunistic infections, particularly those associated with AIDS, immune reconstitution after initiation of antiretroviral therapy can create a rebound inflammatory response that is damaging to the infected organ. This complication was named the immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS).28,29 IRIS may become manifest in patients with AIDS-associated PML treated with antiretroviral therapy and was recognized in patients with MS in whom natalizumab was stopped after recognition of PML infection, leading to an immune response that is damaging to the brain. Treating PML in this complex context of immunosuppressive disease has created uncertainty about treatment and challenges for the future. PATHOGENESIS The viral structure of JC virus demonstrates that it is double-stranded DNA human polyomavirus. The virus is acquired in childhood or young adulthood.5 It is thought to enter the body by a respiratory or oral route. Latency is established in the body after infection. At least 50% of adults are sero- 1376 www.aan.com/continuum positive; recent interest in stratifying patients with MS who are candidates for natalizumab therapy reconfirmed a seroprevalence in this patient population of adults as 50% to 60%.30 Seropositive individuals harbor latent virus in the kidney, lymphoreticular tissue, or brain. This occurs after primary infection, but no illness is produced. Periodic asymptomatic systemic reactivation also occurs without consequence, principally detected as asymptomatic shedding of virus in the urine. PML is considered a JC virus reactivation infection in which a second event occurs. When reactivation of viral replication occurs systemically, immunosuppression may cause dissemination to the brain. However, it is also possible that latency reactivation occurs in the brain and causes PML (Figure 7-1).31 It is likely that JC virus is carried into the brain via white blood cells. Clinically, this has been suspected because the subcortical gray-white junction localization is typical of PML. Clinically and pathologically this represents an end arteriole location for hematogenously disseminated cells, as occurs in brain abscesses and metastatic brain carcinoma. The cell that carries JC virus into the brain remains uncertain. B cells and glia share a common DNA binding factor that may tie them in pathogenesis.32 One hypothesis suggests B cells carry the virus. JC virus can sometimes be found in B cells of the bone marrow, and cells identified as B cells by flow cytometry performed on blood of immunosuppressed patients can contain JC virus.10 A study using double-labeling techniques that evaluated lesions with inflammation and identified B cells in PML lesions did not demonstrate JC virus.31 Other studies suggest that JC virus can be present.10 The timing of JC virus entry into the nervous system relative to the development of PML is controversial December 2012 Copyright @ American Academy of Neurology. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited. Pathogenesis of JC virus infection causing progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. The virus is acquired in childhood or young adulthood and becomes latent in lymphocytes, spleen, kidney, bone marrow, and other lymphoid tissue. It also may establish latency in the brain. With immunosuppression, JC virus replicates in oligodendrocytes; kills them, causing demyelination; and nonproductively infects astrocytes, causing bizarre histologic changes. FIGURE 7-1 Reprinted with permission from Aksamit AJ Jr, Microsc Res Tech.31 onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ jemt.1070320405/abstract. and important in pathogenesis. One hypothesis suggests that JC virus reacts in nonbrain organs, such as the spleen, lymph node, or kidney, and then is hematogenously disseminated during immunosuppression to the nervous system, causing oligodendrocyte infection. A second hypothesis suggests that JC virus infection occurs in childhood or adolescence, and dissemination occurs via the bloodstream to the brain at the time of primary infection. Latency is established in the brain at this time in this model. Then, with the onset of immunosuppressive illness, the virus is reactivated and causes PML. This pathogenesis is important to treatment and immune surveillance of the brain. This second hypothesis is suggested in a study of natalizumab-treated cases in which no JC virus was detected Continuum Lifelong Learning Neurol 2012;18(6):1374–1391 before PML developed in two of three patients.24,25,33 JC virus produces different cellular pathology in oligodendrocytes than in astrocytes, but the mechanism for the distinct pathology in the glial cells of the same patient is unclear. In oligodendrocytes, JC virus infection is lytic. The virus infects the cell and undergoes DNA replication and synthesis of viral capsid proteins. The virus infects adjacent cells from a central nidus of infection, leading to a circumferential expansion of demyelinated lesions.31 Astrocytes, on the other hand, take on a bizarre morphologic appearance, with marked enlargement of the cells and distortion of the nuclei with enlargement or multiple nuclei. These cells are similar to those seen in giant cell astrocytomas unrelated to JC virus www.aan.com/continuum Copyright @ American Academy of Neurology. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited. 1377 Progressive Multifocal Leukoencephalopathy KEY POINT h Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy produces cerebral focal syndromes more commonly than brainstem or cerebellar syndromes, but either can occur. infection. Electron microscopic examination of these cells shows no virions present. In situ hybridization and, to a lesser extent, immunohistochemistry for viral proteins show that these cells are infected in a nonproductive fashion.16 They have a ‘‘transformed’’ appearance in an oncogenic sense. The role of JC virus in human astrocytomas is uncertain and controversial.8,9 CLINICAL PML presents clinically as a focal or multifocal neurologic disorder. The disease, progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, was named for neuropathologic observation of microscopic multifocal lesions involving the brain white matter.1,31 However, clinically, a more typical presentation is of a unifocal syndrome of cerebral or brainstem dysfunction. The frequency of MRI focal versus multifocal abnormalities at the time of clinical presentation differs among various authors. Some regard PML to have typically multifocal changes on MRI, even with unifocal clinical presentation. Others suggest that most patients present with a unifocal MRI scan and clinical unifocal syndrome simultaneously.31 Whichever is correct, a multifocal or unifocal PML clinical presentation is possible. The neurologic presentation of PML reflects varying locations of the brain affected. Motor system involvement causes corticospinal tract findings. Cortical sensory loss, ataxic cerebellar deficits, and focal visual field defects are common. ‘‘Cortical’’ deficits, such as aphasia or visual-spatial disorientation, can occur because PML demyelination is often immediately subcortical, undermining the cerebral cortex identified with the clinical syndrome. Most patients with PML without AIDS have neurologic focal deficits from cerebral hemisphere abnormalities. The ratio of cerebral versus brainstem in- 1378 www.aan.com/continuum volvement is approximately 10:1. For reasons that are unclear, brainstem involvement happens more commonly in patients with PML who have AIDS, with a cerebral to brainstem ratio of involvement approximating 4:1. A patient with immunosuppression characterized as a cell-mediated immunity defect who develops a subacute focal progressive neurologic syndrome should undergo a search for PML. Although JC virus infection has been historically regarded as a ‘‘slow virus’’ infection, the illness of PML is subacute in progression with focal worsening of neurologic symptoms evolving over days to weeks. Sometimes the focal neurologic syndrome can seem acute and be suggestive of a stroke mechanism. Inevitably with PML, serial neurologic examinations demonstrate subacute neurologic worsening. The MRI of the brain parallels the clinical changes over time. Patients with more immunopreserved status may have a slower clinical course, mimicking brain tumors such as CNS lymphoma or glioma (Figure 7-2). Weakness or paralysis occurs in 60% of patients with PML.11Y13 Gait abnormalities are common and occur in up to 65% of patients at presentation, and cognitive disorders are the presenting manifestation in 30%. Presenting manifestations are most commonly memory concerns or a behavioral disorder. Cognitive disturbances are present in most cases with clinical progression in the cerebral hemispheres. Aphasia occurs in 20%. Visual field defects are the presenting manifestation in 20%. Focal cortical sensory loss (proprioception loss, astereognosis) is common but poorly quantitated as to frequency of occurrence. Cortical limb monoparesis, limb apraxia, unilateral ataxia, or focal brainstem signs can all occur. Seizures are infrequent but estimated to occur in 10% of patients. Illnesses associated with nonAIDS PML are shown in Table 7-1. December 2012 Copyright @ American Academy of Neurology. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited. AIDS AIDS is the most common mechanism of immunosuppression leading to PML. It is estimated that PML affects 1% to 4% of symptomatic AIDS cases. PML can be the presenting manifestation of AIDS. However, more commonly, PML occurs with low CD4 blood counts (less than 200 cells/2L) and occurs later in the course of AIDS disease. As an opportunistic infection, PML incidence has been less affected by combination antiretroviral therapy than other opportunistic infections of the nervous system, such as toxoplasmosis or cryptococcal meningitis (Case 7-1). LYMPHORETICULAR MALIGNANCY The lymphoreticular malignancies are the most common non-AIDS-related cause of immunosuppression predisposing to PML. The most common disorders are chronic lymphocytic leukemia, Hodgkin disease, and non-Hodgkin lymphoma. It is interesting that chronic lymphocytic leukemia and most nonHodgkin lymphomas are generally regarded as neoplasms of B-cell lineage. Yet all of these disorders are well known to be associated with opportunistic infections that manifest as disorders of T-cell immune deficiency, such as toxoplasmosis or cryptococcal meningitis. Therefore, the precise immune defects that predispose to PML in these malignancies remain ill defined. RHEUMATOLOGIC DISORDERS Virtually any form of rheumatologic disorder has been reported to be associated with PML. Since these autoimmune disorders are commonly treated with immunosuppressive agents, it is unclear whether the underlying disease or the treatment is primarily responsible for the predisposition to PML. In a study looking at underlying disorders in nonAIDS PML (Table 7-1), the frequency of Continuum Lifelong Learning Neurol 2012;18(6):1374–1391 T2-weighted fluid-attenuated inversion recovery brain MRI scan of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML). Bifrontal PML lesions including involvement of the corpus callosum mimicking glioma or lymphoma. FIGURE 7-2 connective tissue diseasesVrheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, dermatomyositis, and vasculitis with methotrexate and cyclophosphamideVwas 16%. Estimates of PML incidence in patients with rheumatoid arthritis suggest the frequency is low, approximately 0.4 per 100,000 discharges.35 KEY POINT h Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy primarily occurs in immunosuppressed illnesses of T-cell deficit, ie, AIDS or lymphoreticular malignancy. TRANSPLANTATION PML is an important but rare cause of neurologic disease in transplant recipients. A recent study found the estimated incidence of PML in patients receiving heart and/or lung transplant occurring approximately 1.24 per every 1000 transplant person-years.36 Mean onset of PML symptoms after transplantation was 17 months. PML is most often fatal (84% case fatality) in this population but is compatible with recipient survival measured in years (3 of 50 patients). The risk of PML likely exists throughout the entire posttransplant period and should be suspected www.aan.com/continuum Copyright @ American Academy of Neurology. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited. 1379 Progressive Multifocal Leukoencephalopathy TABLE 7-1 Progressive Multifocal Leukoencephalopathy Patients at Mayo Clinic: Non-AIDS Progressive Multifocal Leukoencephalopathy—Associated Diseases (n=58) b Lymphoreticular Malignancy (n=32, 55%) Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (n=14, 24%) Hodgkin disease (n=6, 10%) Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (n=12, 21%) b Connective Tissue Diseases (n=9, 16%) Rheumatoid arthritis (n=3, 5%) Systemic lupus erythematosus (n=4, 7%) Dermatomyositis (n=1, 2%) Vasculitis with methotrexate and cyclophosphamide (n=1, 2%) b Organ Transplantation (n=4, 7%) Renal transplantation Liver transplantation Heart transplantation b Granulomatous Disease (n=5, 9%) Sarcoidosis b Other (n=4, 7%) Cirrhosis Pulmonary fibrosis Diabetes mellitus, pulmonary histoplasmosis, and prednisone b ‘‘Normal Aged’’ Patients With No Immunosuppression (n=4, 7%) Patients aged 66, 76, and 80 years and quickly diagnosed because temporary reduction of immunosuppression may be compatible with PML improvement and long-term patient survival. The case fatality among patients who develop PML posttransplantation is high, with death occurring within 18 months in most cases. Exceptions to this occur. In one series, three patients were still alive at 13, 44, and 155 months following PML symptom onset.36 Among survivors, all patients had their immunosuppressive drug regimen significantly reduced or withdrawn at the time of diagnosis of PML. No 1380 www.aan.com/continuum patient survived without immunosuppressive medication reduction. Graft rejection is of significant concern with immunosuppressive drug reduction but consistent with survival in some cases of PML. MULTIPLE SCLEROSIS TREATED WITH NATALIZUMAB Natalizumab, a monoclonal antibody directed against the !4 integrin molecule, was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in November 2004 for treatment of patients with MS after a controlled trial.37 By February December 2012 Copyright @ American Academy of Neurology. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited. Case 7-1 A 55-year-old right-handed man had received a diagnosis of HIV disease 8 months earlier. He recently went through a series of changes in his antiretroviral drug regimen and had persistent nausea despite multiple changes of his medications. His CD4 count was 386 cells/2L, and HIV serum quantitation was less than 400 copies of RNA/mL. For 2 months he had unsteadiness of gait and progressive decline in balance, more prominent on the left side and affecting the left lower extremity. Change in control of the left upper extremity with the unsteadiness also occurred. In the prior 1 month he also noticed some diplopia. His examination showed that his gait and station were impaired by marked ataxia. He could stand independently only with support. Ataxia was present in the left upper and lower extremities. Nystagmus occurred on lateral gaze and mild conjugate gaze paresis on the gaze to the left. Extraocular movements were otherwise full, and pupils were normal. Diffuse hyperreflexia was present, but plantar responses were flexor. The remainder of the neurologic examination was unremarkable. MRI scan of the head showed increased fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) signal involving the cerebellar white matter of the left cerebellar hemisphere and extending into the pons through the middle cerebellar peduncle (Figure 7-3). The abnormality produced little mass effect. No contrast enhancement was present on postgadolinium images. Spinal fluid protein concentration was 104 mg/dL with 2 nucleated cells/2L. CSF Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) testing was nonreactive. Results from the following tests were negative: cryptococcal antigen, cytology, blood serology for toxoplasmosis, and PCR assays for toxoplasmosis and Epstein-Barr virus in the spinal fluid. PCR of spinal fluid for JC virus was ‘‘indeterminate’’ positive. Two of four specimens tested positive, with one each of duplicate specimens run twice showing JC virusYspecific PCR detection. The diagnosis was PML. Comment. PML in AIDS typically occurs in patients who have had HIV disease with more severe immunosuppression. Usually CD4 counts are less than 200 cells/2L. However, immunosuppression does not reliably predict pathology, and PML can occur with normal CD4 counts. The presentation with cerebellar or brainstem disease is more common in AIDS than FIGURE 7-3 T2-weighted fluid-attenuated inversion recovery brain MRI scan non-AIDS cases. PCR testing for JC virus in the spinal of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML). Left cerebellar and fluid of patients with PML has 76% sensitivity, pontine PML lesion. combining a number of studies. A positive PCR finding abolishes the need for brain biopsy. The indeterminate result is a reflection of the assay operating at the limits of detection and is a reason why not all patients with PML test positive by this method. The need for brain biopsy in PCR-negative cases depends on clinical circumstances, including localization of the lesion, social situation, and therapeutic options. This patient was treated with cidofovir and significantly improved.34 Whether the improvement was an effect of cidofovir, the immunologic restoration by the cART regimen (which was stable throughout the PML course), or both is open to interpretation. 2005, two patients with MS who had been treated with natalizumab therapy were diagnosed with PML, leading to the Continuum Lifelong Learning Neurol 2012;18(6):1374–1391 withdrawal of natalizumab from the market. One patient died.24 The second patient, with PML proven by brain biopsy, www.aan.com/continuum Copyright @ American Academy of Neurology. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited. 1381 Progressive Multifocal Leukoencephalopathy KEY POINT h Exogenous immunosuppressive treatments such as natalizumab and rituximab have been linked to progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy occurrence. had an unstable clinical course. He developed severe clinical deficits and IRIS when natalizumab was stopped.25 Another case of PML related to natalizumab was recognized in a patient being treated for Crohn disease. He died of a progressive syndrome, which was initially diagnosed as astrocytoma. A rereview of neuropathology revealed PML.33 The long duration of therapy and prior immunosuppressant exposure has been consistent with other cases of PML. In transplantation, where the date of immunosuppression can be accurately determined, PML occurs late (usually longer than 1 year) after immunosuppressants are introduced. Since that time, natalizumab has been reintroduced to the market with a close monitoring system and a registry of patients administered by Biogen Idec, and with data available to physicians online for assessment of risk to patients (medinfo.biogenidec.com/medinfo). Several aspects have emerged from the data about these patients.23 The incidence of PML is dependent on the duration of natalizumab use and substantially increased after 24 months of use. Incidence of confirmed PML in patients who have had 24 or more infusions of natalizumab is now estimated to be one case of PML per 1000 patients.23 As of May 1, 2012, BiogenIdec reported 242 cases of natalizumabassociated PML. Of these, 20% have died. Those who have survived experienced varying degrees of disability. Seropositivity for JC virus in the blood increases incidence of natalizumabassociated PML to as much as one per 100 patients after 2 years of use. Finally, prior exposure to other immunosuppressive drugs also increases the risk of PML (Case 7-2). OTHER DRUGS Other specific immunosuppressant drugs that can predispose to PML are predni- 1382 www.aan.com/continuum sone, methotrexate, cyclophosphamide, and cyclosporine.26 It is also apparent that newer immunosuppressives, such as leflunomide, can predispose to developing PML.38 The exact risk with use of these drugs, such as monoclonal antibodies targeting lymphocyte trafficking or antagonizing specific cytokines, remains to be defined on an individual basis. Mycophenolate mofetil is used for a variety of B- and T-cell disorders. It was initially developed as a posttransplant antirejection drug. However, the drug is used off-label for many other autoimmune disorders because of its favorable side-effect profile. The presence of PML in patients treated with mycophenolate mofetil has been reported. Online resources may help with risk assessment (www.gene.com/gene/ products/information/cellcept/), and this subject has been covered in a recent review.26 Rituximab is a therapeutic monoclonal anti-CD20 antibody that targets B cells selectively and removes them from the circulation. This monoclonal antibody has been used to treat a variety of B-cell neoplasms (eg, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, lymphoma) and autoimmune diseases, specifically rheumatoid arthritis, and off-label for systemic lupus erythematosus. PML has been shown to occur in rituximab-treated patients.27,39 It is estimated that the risk is approximately one per 25,000 patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with rituximab.27 Systemic lupus erythematosus may have a higher propensity to PML.27 Another monoclonal anti-CD11a antibody named efalizumab was marketed for the treatment of refractory psoriasis. It was withdrawn from the United States market as of June 2009 because of PML occurring in patients treated with this drug. The frequency was estimated to be four of 46,000 patients treated.40 However, whether the rare occurrence of a usually fatal neurologic December 2012 Copyright @ American Academy of Neurology. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited. Case 7-2 A 54-year-old right-handed woman was diagnosed with MS after experiencing diplopia. She had an abnormal multifocal MRI scan reported by her local neurologist. Spinal fluid showed absent oligoclonal banding, normal IgG index, normal protein concentration, and 3 white cells. Three years later, natalizumab was started for treatment of multiple sclerosis. One year after starting her natalizumab therapy, she developed progressive weakness of the left hand, which progressed and spread during 1 month so that she essentially had left hemiplegia. Her treatment with natalizumab had been discontinued at the beginning of her worsening symptoms. MRI scan of the head showed an enlarging lesion of T2 hyperintensity involving the white matter in the right cerebral hemisphere, extending from the deep white matter up to the superficial cortex, and involving the precentral gyrus and premotor subcortical white matter of the right hemisphere (Figure 7-4). This worsened despite 4 days of IV methylprednisone 1 g/d. Spinal fluid testing was repeated and showed glucose concentration of 71 mg/dL, protein concentration of 48 mg/dL, and no white blood cells; PCR was positive for JC virus. Comment. The patient developed PML after starting natalizumab therapy. A progressive neurologic deficit, with subcortical white matter imaging abnormalities that are worsening subacutely, would strongly suggest a diagnosis of PML. PML needs to be considered with high index of suspicion in patients on natalizumab therapy. The patient received three plasma exchanges to shorten the period in which natalizumab remained T2-weighted fluid-attenuated FIGURE 7-4 inversion recovery brain MRI scan active. She was at increased risk for developing IRIS, of progressive multifocal which subsequently needed treatment. IRIS is leukoencephalopathy (PML). Right frontal large more common and more severe in patients with PML lesion with tiny left frontal lesions. natalizumab-associated PML than in patients with HIV-associated PML. infection should prohibit drugs such as this from use in all cases is uncertain. Screening by serologic means allows one to determine whether a patient carries latent JC virus.30 Since PML is regarded as a reactivation infection, this serologic testing has been proposed as a screening tool so that these immunosuppressives are used only with great caution in seropositive individuals. No reliable method is available to detect PML before symptoms. A positive JC virus serology predicts predisposition to infection. CSF PCR Continuum Lifelong Learning Neurol 2012;18(6):1374–1391 techniques or brain biopsy currently are the only methods to confirm PML. SARCOIDOSIS Systemic sarcoidosis is associated with defects in cell and humoral immunity, with a granulomatous pathologic reaction. Many reports have been published of PML occurring in patients with sarcoidosis. However, it is unclear whether the predisposition to PML is part of the primary disease or a result of the immunosuppressive treatment often used chronically to treat the disease, such as www.aan.com/continuum Copyright @ American Academy of Neurology. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited. 1383 Progressive Multifocal Leukoencephalopathy KEY POINTS h Radiologic evaluation should be done by MRI scan in suspected cases. h The principal MRI finding is T2 or fluid-attenuated inversion recovery subcortical white matter demyelination. h PCR for JC virus in the spinal fluid is only 70% to 75% sensitive in progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy cases. prednisone or methotrexate. Some patients with sarcoidosis who develop PML are on no active treatment. In either case, PML is an infrequent opportunistic infection in patients with sarcoidosis, although incidence data are lacking. In a series of non-AIDS PML cases, sarcoidosis was present in 9% of the patients (Table 7-1). RADIOLOGIC FEATURES An MRI scan of the head is more sensitive than a CT scan for detecting abnormalities related to PML (Table 7-2).41 A normal MRI head scan would argue against PML as the cause of neurologic deficits. Rarely, patients with PML have clinically detectable neurologic deficits and no MRI abnormalities. MRI abnormalities are typically localized to the subcortical white matter at the graywhite junction (Figure 7-2, Figure 7-4, and Figure 7-5A, B, and C). The lesions show increased T2 signal, no or little mass effect, and minimal or no enhancement after gadolinium administration (Figure 7-5C and D). These characteristics have exceptions with PML. Any cerebral lobe is potentially vulnerable to disease. Some authors have suggested that occipital PML is more common.41 Presumably some of the variability of the presenting syndrome represents the neurologic deficit effect on the patient’s functions of daily living. Any area of the white matter areas of the brainstem can be affected. More common is involvement of the cerebellum. A focal abnormality on MRI scan in the brainstem would suggest PML when little mass effect and no contrast enhancement are present. DIAGNOSTIC TESTS PCR has been used to amplify JC virus DNA from the spinal fluid of patients with PML. Current studies of JC virus show that CSF detection is specific for pathologically significant PML.19,20,42,43 All studies have been retrospective analyses of spinal fluid specimens of patients with either pathologically confirmed or clinically suspected PML, based on MRI and coincident underlying immunosuppressive illness. Sensitivity of detection is not 100%. Specifically, combined data from published studies show that 76% were correctly diagnosed by this assay. It is unclear why false negatives occur. The most likely explanation is low abundance of virus DNA in spinal fluid. Other possible explanations include storage TABLE 7-2 Brain MRI Findings b MRI T2 and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery are most sensitive b Lesions typically localize to subcortical white matter more commonly than periventricular regions b Gadolinium nonenhancing or minimally enhancing (unless immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome is present) b Almost always abnormal b Regional expression: Frontal equals occipital Unifocal greater than multifocal Cerebral greater than brainstem 1384 www.aan.com/continuum December 2012 Copyright @ American Academy of Neurology. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited. Brain MRI scan of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML). All are T2-weighted fluid-attenuated inversion recovery images except D, which is a T1 postgadolinium image. A, Single superficial subcortical left frontal PML lesion. B, Multifocal right-greater-than-left subcortical frontal PML lesions. C, D, Symmetric bioccipital PML lesions that show trace enhancement after gadolinium. FIGURE 7-5 and handling of specimens, small volume of spinal fluid assay, inhibitors in the spinal fluid, and loss of DNA during CSF concentration. Combining data from studies,19,43,44 the false-positive rate identifying CSF specimens from AIDS patients without PML or other controls was only 2%. Sensitivity of 75% has been borne out in larger studies.42 If PML is suspected and PCR for JC virus is negative, the recommendation is to repeat Continuum Lifelong Learning Neurol 2012;18(6):1374–1391 the assay and consider a laboratory capable of detecting low copy numbers of JC virus DNA. The other spinal fluid chemistry and cell count findings in patients with PML are typically nonspecific. Minimal pleocytosis occurs, but the finding is usually less than 20 cells/2L. More than 20 cells/2L suggests the possibility of a different infection or restored immunity of the host with reaction against JC virus. A spinal www.aan.com/continuum Copyright @ American Academy of Neurology. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited. 1385 Progressive Multifocal Leukoencephalopathy KEY POINT h In suspected progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy cases with negative CSF PCR for JC virus, the PCR should be repeated with consideration of a laboratory capable of detecting low DNA copy numbers, or the patient should be taken to brain biopsy. fluid pleocytosis can be seen when contrast enhancement increases on the brain MRI. Pleocytosis correlates with the neuropathologic finding of perivascular lymphocytic cuffing in the brain. Spinal fluid protein is only moderately elevated, usually less than 100 mg/dL. Culture for JC virus is unrevealing. PATHOLOGY When spinal fluid PCR is negative for JC virus, a brain biopsy of suspected PML lesions is advised in order to confirm diagnosis. Immunohistochemistry or in situ hybridization are the best techniques for confirming JC virus in a biopsy specimen.15,16,45 Oligodendrocytes at the gray-white matter junction are the most common site for infection (Figure 7-6A). The spectrum of neuropathology in the brain of JC virus infection in patients with PML has been changed. JC virus infects oligodendrocytes, astrocytes, and now granule cell neurons of the cerebellum. The demyelination of PML is secondary to oligodendrocyte infection and death.1 Demyelination expands in a circumferential way to produce plaques easily demonstrated on myelin stains (Figure 7-6B). Histology of PML shows nuclear enlargement of infected oligodendrocytes. Virion accumulations produce the ‘‘inclusion-bearing’’ nuclei of oligodendrocytes. Oligodendrocyte nuclei are enlarged, with ground-glass appearance, and amphophilic, basophilic, or sometimes eosinophilic staining after hematoxylin and eosin. The death of oligodendrocytes leads to release of virus and infection of neighboring cells. Virus spreads circumferentially from a central nidus to neighboring cells, leading to expansion of demyelination.31 The number of oligodendrocytes infected with JC virus by in situ hybridization is more numerous than would be suspected based on nuclear enlargement.16 On electron microscopy, oligodendrocyte nuclei are filled with JC icosahedral virions approximately 40 nm in size. The size helps to identify JC virus. Accompanying tubular forms of immature Pathology of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML). Gross and microscopic appearance of PML lesions affecting the superficial subcortical gray-white matter junction in the cerebral hemisphere. A, This is a coronal section of fixed PML brain. The subcortical white matter is undermined by multifocal punctate coalescent demyelinating lesions (black arrows). B, Luxol fast blue stain shows a microscopic demyelinated lesion (between opposing black arrows) in the white matter immediately subcortical. The cortex and neuronal cell bodies are in the left of the picture (original magnification 430). FIGURE 7-6 1386 www.aan.com/continuum December 2012 Copyright @ American Academy of Neurology. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited. capsid protein may assemble in the nucleus. Bizarre astrocytes are a nonlytic JC virus infection of astrocytes. These cells look bizarre with enlarged and multilobulated nuclei. They look like neoplastic cells but do not form frank tumors. Rare reports of gliomas in PML lesions have occurred.7 More commonly, the PML can be misdiagnosed as glioma because of the cell atypia.33 Bizarre astrocytes have limited JC virus DNA replication by in situ hybridization and viral capsid immunohistochemistry. They do not, however, produce significant virions based on electron microscopic analysis.31,45 Double-labeling techniques have shown that granule cell neurons of the cerebellum are infectible with JC virus.18,46 Granule cell neurons show lytic infection and cell death with atrophy of the granule cell layer of the cerebellum.46 The pathology is associated with limited or no inflammation. This is regarded to be proportional to the immune state of the host. More severe immunosuppression is associated with little or no inflammation. Patients have had immune reconstitution and developed IRIS in the nervous system in the context of AIDS.47 KEY POINT h No satisfactory antiviral therapy is available for the treatment of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. TREATMENT No treatments have proven to be effective for PML (Table 7-3). General principles about treatment include improvement in immune status. Antiviral therapy may promote survival.48 Therapies can be offered if the goal of neurologic stabilization satisfies the patient’s quality-of-life goals. Although the prognosis of PML is generally dismal, removal of the immunosuppression influence of an external drug allows the patient’s own immune system to clear JC virus from the brain. This is an effective approach but can also lead to IRIS, which, when it occurs in the brain after immune restoration, may need treatment. IRIS should be treated if TABLE 7-3 Treatment Options b Immune Reconstitution Stop immunosuppressants Optimize antiretroviral therapy (in AIDS) b Nucleoside Analogs (Questionable Effectiveness) Cytosine arabinoside 2 mg/kg/d for 5 days, single course Cidofovir 5 mg/kg once weekly for 2 weeks, then every 2 weeks for 2 months b Treatments Not Likely to Work Interferon alpha Topotecan 5-hydroxytryptamine antagonists Chlorpromazine Mirtazapine Risperidone Mefloquine Continuum Lifelong Learning Neurol 2012;18(6):1374–1391 www.aan.com/continuum Copyright @ American Academy of Neurology. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited. 1387 Progressive Multifocal Leukoencephalopathy KEY POINTS h Patients with progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy associated with AIDS should have optimization of antiretroviral therapy. h Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome should be treated if it is associated with significant neurologic deterioration. 1388 accompanied by neurologic deterioration with short-term corticosteroids. In patients with AIDS, cART should be initiated. If the patient with AIDS is already receiving cART, therapy should be changed to optimize immune restoration and normalization of the CD4 count. Cytosine arabinoside has failed in patients with AIDS-related PML.22 For deteriorating patients with PML with or without AIDS, cidofovir can be considered,34,49 although several studies have suggested it is ineffective.50,51 For patients with PML without AIDS, no effective therapy is available. If the goal to stabilize neurologic deterioration is acceptable in the clinical context of the systemic disease, however, one may consider IV cytosine arabinoside 2 mg/kg/d for 5 days. A single nonblinded study showed an approximately 30% response rate in patients in whom 85% mortality was expected within 1 year.48 Mirtazapine or risperidone have also been suggested as options for treatment, but their effectiveness is not yet proven. The receptor for JC virus entry into the cell is identified as a subtype of the serotonin receptors 5hydroxytryptamine 2A (5-HT2A).52 This is combined with a sialic acidYN-linked glycoprotein on the cell membrane. This report has led to treatment of PML with psychotropic medications known to block the 5-HT2A receptor. Mirtazapine is an antidepressant, and risperidone is an antipsychotic proposed to be specific for blockade of this receptor. Mirtazapine has been used anecdotally at 15 mg/d to 30 mg/d, in patients with nonYAIDS-related PML. 53,54 These patients also had alteration of their immunosuppressive regimen and treatment with other agents, including cytosine arabinoside or cidofovir. Risperidone has been suggested to be potentially more potent.55 None of this form of therapy blocking the serotonin receptor has www.aan.com/continuum been successful, although no blinded prospective trials have been published. Mefloquine has been suggested to be potentially helpful based on in vitro screening of compounds with activity against JC virus. Mefloquine hydrochloride was used in several cases of rituximabassociated PML.27 However, a recent clinical trial was stopped for lack of demonstrable efficacy.56 Interferon alpha has been rarely reported to have some success in treating PML; however, the patients were treated with multiple agents, making these reports difficult to interpret. Current consensus is that interferon alpha is not helpful in the treatment of PML.18 Interferon beta also seems to be of no help.57 Camptothecin and topotecan, two DNA topoisomerase inhibitor drugs, have antiviral activity against JC virus. These drugs are antineoplastic agents. Few case reports of treating PML have been published.58 No series of PML patients treated suggest that these drugs are successful. IMMUNE RECONSTITUTION INFLAMMATORY SYNDROME IRIS can occur after withdrawal of the immunosuppressive agent and after PML diagnosis. The immune response is important in clearing JC virus from the brain. Therefore, at least limited inflammation is probably important in neurologic survival.28 IRIS, however, is thought to be injurious to the brain, and many patients need additional treatment. Treatment is typically a short course of high-dose IV methylprednisolone, usually 1 g/d for 5 days.29 However, universal consensus is lacking on route, type, dose, or duration of corticosteroid therapy. Despite treatment success and survival, PML deficits can be expected to be permanent. In the circumstance of natalizumabassociated PML, management of the PML has routinely used plasma exchange December 2012 Copyright @ American Academy of Neurology. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited. or immunoabsorption to hasten clearance of the drug and shorten the period in which natalizumab remains active (usually several months). Exacerbation of symptoms and enlargement of lesions on MRI have occurred within a few days to a few weeks after plasma exchange, indicative of IRIS. This syndrome seems to be more common and more severe in patients with natalizumab-associated PML than in patients with HIV-associated PML treated with cART. PROGNOSIS In general, PML has been regarded as nearly a universally fatal disease. However, more recent experience with PML suggests that patients can survive. A preAIDS era study showed the 4-month survival rate to be 30%, and the 12-month survival rate 15%.13 In the pre-cART era, AIDS-related PML was fatal in 95% of patients in 6 months.46 Institution of optimized cART therapy has produced 50% survival at 1 year.50 Natalizumab-associated PML has had a higher survival rate of 80% (medinfo. biogenidec.com/medinfo), although PMLassociated deficits are expected to be permanent. These patients usually also require treatment of IRIS. REFERENCES 1. Astrom KE, Mancall EL, Richardson EP Jr. Progressive multifocal leuko-encephalopathy; a hitherto unrecognized complication of chronic lymphatic leukaemia and Hodgkin’s disease. Brain 1958;81(1):93Y111. 2. Richardson EP Jr. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. N Engl J Med 1961;265:815Y823. KEY POINT 5. Walker D, Frisque R. The biology and molecular biology of JC virus. In: Salzman NP, ed. The papovaviridae. New York: Plenum Press, 1986. h Patients with natalizumab-associated progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy should have plasma exchange to speed removal of the drug. 6. Weiner LP, Herndon RM, Narayan O, et al. Isolation of virus related to SV40 from patients with progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. N Engl J Med 1972;286(8):385Y390. 7. Castaigne P, Rondot P, Escourolle R, et al. [Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy and multiple gliomas.] Rev Neurol (Paris) 1974;130(9Y10):379Y392. 8. Del Valle L, Azizi SA, Krynska B, et al. Reactivation of human neurotropic JC virus expressing oncogenic protein in a recurrent glioblastoma multiforme. Ann Neurol 2000;48(6):932Y936. 9. Major EO. From telomeres to T-antigens: many roadsImultiple pathwaysInovel associations in the search for the origins of human gliomas. Ann Neurol 2000;48(6):823Y825. 10. Major EO, Amemiya K, Tornatore CS, et al. Pathogenesis and molecular biology of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, the JC virus-induced demyelinating disease of the human brain. Clin Microbiol Rev 1992;5(1):49Y73. 11. Berenguer J, Miralles P, Arrizabalaga J, et al. Clinical course and prognostic factors of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in patients treated with highly active antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis 2003;36(8):1047Y1052. 12. Berger JR, Pall L, Lanska D, Whiteman M. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in patients with HIV infection. J Neurovirol 1998;4(1):59Y68. 13. Brooks BR, Walker DL. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Neurol Clin 1984;2(2):299Y313. 14. Frisque RJ, Bream GL, Cannella MT. Human polyomavirus JC virus genome. J Virol 1984;51(2):458Y469. 3. Zurhein G, Chou SM. Particles resembling papova viruses in human cerebral demyelinating disease. Science 1965;148(3676):1477Y1479. 15. Aksamit AJ, Mourrain P, Sever JL, Major EO. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy: investigation of three cases using in situ hybridization with JC virus biotinylated DNA probe. Ann Neurol 1985;18(4):490Y496. 4. Padgett BL, Walker DL, ZuRhein GM, et al. Cultivation of papovalike virus from human brain with progressive multifocal leucoencephalopathy. Lancet 1971;1(7712):1257Y1260. 16. Aksamit AJ, Sever JL, Major EO. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy: JC virus detection by in situ hybridization compared with immunohistochemistry. Neurology 1986;36(4):499Y504. Continuum Lifelong Learning Neurol 2012;18(6):1374–1391 www.aan.com/continuum Copyright @ American Academy of Neurology. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited. 1389 Progressive Multifocal Leukoencephalopathy 17. Houff SA, Major EO, Katz DA, et al. Involvement of JC virus-infected mononuclear cells from the bone marrow and spleen in the pathogenesis of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. N Engl J Med 1988;318(5):301Y305. 18. Koralnik IJ. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy revisited: has the disease outgrown its name? Ann Neurol 2006;60(2):162Y173. 19. McGuire D, Barhite S, Hollander H, Miles M. JC virus DNA in cerebrospinal fluid of human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients: predictive value for progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Ann Neurol 1995;37(3):395Y399. 20. Telenti A, Marshall WF, Aksamit AJ, et al. Detection of JC virus by polymerase chain reaction in cerebrospinal fluid from two patients with progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 1992;11(3):253Y254. 21. Ryschkewitsch CF, Jensen PN, Monaco MC, Major EO. JC virus persistence following progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in multiple sclerosis patients treated with natalizumab. Ann Neurol 2010;68(3):384Y391. 22. Hall CD, Dafni U, Simpson D, et al. Failure of cytarabine in progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy associated with human immunodeficiency virus infection. AIDS Clinical Trials Group 243 Team. N Engl J Med 1998;338(19):1345Y1351. 23. Clifford DB, De Luca A, Simpson DM, et al. Natalizumab-associated progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in patients with multiple sclerosis: lessons from 28 cases. Lancet Neurol 2010;9(4):438Y446. 24. Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK, Tyler KL. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy complicating treatment with natalizumab and interferon beta-1a for multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med 2005;353(4):369Y374. 25. Langer-Gould A, Atlas SW, Green AJ, et al. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in a patient treated with natalizumab. N Engl J Med 2005;353(4):375Y381. 26. Berger JR, Houff S. Opportunistic infections and other risks with newer multiple sclerosis therapies. Ann Neurol 2009;65(4):367Y377. 1390 29. Tan K, Roda R, Ostrow L, et al. PML-IRIS in patients with HIV infection: clinical manifestations and treatment with steroids. Neurology 2009;72(17):1458Y1464. 30. Bozic C, Richman S, Plavina T, et al. Anti-John Cunningham virus antibody prevalence in multiple sclerosis patients: baseline results of STRATIFY-1. Ann Neurol 2011;70(5):742Y750. 31. Aksamit AJ Jr. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy: a review of the pathology and pathogenesis. Microsc Res Tech 1995;32(4):302Y311. 32. Major EO, Amemiya K, Elder G, Houff SA. Glial cells of the human developing brain and B cells of the immune system share a common DNA binding factor for recognition of the regulatory sequences of the human polyomavirus, JCV. J Neurosci Res 1990;27(4):461Y471. 33. Van Assche G, Van Ranst M, Sciot R, et al. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy after natalizumab therapy for Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med 2005;353(4):362Y368. 34. Razonable RR, Aksamit AJ, Wright AJ, Wilson JW. Cidofovir treatment of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in a patient receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy. Mayo Clin Proc 2001;76(11):1171Y1175. 35. Calabrese LH, Molloy ES. Progressive multifocal leucoencephalopathy in the rheumatic diseases: assessing the risks of biological immunosuppressive therapies. Ann Rheum Dis 2008;67(suppl 3):iii64Yiii65. 36. Mateen FJ, Muralidharan R, Carone M, et al. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in transplant recipients. Ann Neurol 2011;70(2): 305Y322. 37. Rudick RA, Stuart WH, Calabresi PA, et al. Natalizumab plus interferon beta-1a for relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med 2006;354(9):911Y923. 38. Rahmlow M, Shuster EA, Dominik J, et al. Leflunomide-associated progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Arch Neurol 2008;65(11):1538Y1539. 27. Clifford DB, Ances B, Costello C, et al. Rituximab-associated progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in rheumatoid arthritis. Arch Neurol 2011;68(9):1156Y1164. 39. Carson KR, Evens AM, Richey EA, et al. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy after rituximab therapy in HIV-negative patients: a report of 57 cases from the Research on Adverse Drug Events and Reports Project. Blood 2009;113(20): 4834Y4840. 28. Berger JR. Steroids for PML-IRIS: a double-edged sword? Neurology 2009;72(17):1454Y1455. 40. Korman BD, Tyler KL, Korman NJ. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, efalizumab, and immunosuppression: a www.aan.com/continuum December 2012 Copyright @ American Academy of Neurology. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited. cautionary tale for dermatologists. Arch Dermatol 2009;145(8):937Y942. 41. Whiteman ML, Post MJ, Berger JR, et al. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in 47 HIV-seropositive patients: neuroimaging with clinical and pathologic correlation. Radiology 1993;187(1):233Y240. 42. Bossolasco S, Calori G, Moretti F, et al. Prognostic significance of JC virus DNA levels in cerebrospinal fluid of patients with HIV-associated progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Clin Infect Dis 2005;40(5):738Y744. 43. Weber T, Turner RW, Frye S, et al. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy diagnosed by amplification of JC virus-specific DNA from cerebrospinal fluid. AIDS 1994;8(1):49Y57. 44. Aksamit AJ. Cerebrospinal fluid in the diagnosis of central nervous system infections. In: Roos KL, ed. Central nervous system infectious diseases and therapy. New York, NY: Marcel Dekker, Inc, 1997:731Y745. 45. Aksamit AJ Jr. Nonradioactive in situ hybridization in progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Mayo Clin Proc 1993;68(9):899Y910. 46. Du Pasquier RA, Corey S, Margolin DH, et al. Productive infection of cerebellar granule cell neurons by JC virus in an HIV+ individual. Neurology 2003;61(6):775Y782. 47. Clifford DB, Yiannoutsos C, Glicksman M, et al. HAART improves prognosis in HIV-associated progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Neurology 1999;52(3):623Y625. 48. Aksamit AJ. Treatment of non-AIDS progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy with cytosine arabinoside. J Neurovirol 2001;7(4):386Y390. 49. Viallard JF, Lazaro E, Ellie E, et al. Improvement of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy after cidofovir therapy in a patient with a destructive Continuum Lifelong Learning Neurol 2012;18(6):1374–1391 polyarthritis. Infection 2007;35(1): 33Y36. 50. De Luca A, Ammassari A, Pezzotti P, et al. Cidofovir in addition to antiretroviral treatment is not effective for AIDS-associated progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy: a multicohort analysis. AIDS 2008;22(14):1759Y1767. 51. Marra CM, Rajicic N, Barker DE, et al. A pilot study of cidofovir for progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in aids. AIDS 2002;16(13):1791Y1797. 52. Elphick GF, Querbes W, Jordan JA, et al. The human polyomavirus, JCV, uses serotonin receptors to infect cells. Science 2004;306(5700):1380Y1383. 53. Owczarczyk K, Hilker R, Brunn A, et al. Progressive multifocal leucoencephalopathy in a patient with sarcoidosisVsuccessful treatment with cidofovir and mirtazapine. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2007;46(5):888Y890. 54. Vulliemoz S, Lurati-Ruiz F, Borruat FX, et al. Favourable outcome of progressive multifocal leucoencephalopathy in two patients with dermatomyositis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2006;77(9):1079Y1082. 55. Kast RE, Focosi D, Petrini M, Altschuler EL. Treatment schedules for 5-HT2a blocking in progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy using risperidone or ziprasidone. Bone Marrow Transplant 2007;39(12):811Y812. 56. Clifford D, Nath A, Cinque P, et al. Mefloquine treatment in patients with progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Neurology 2011;76:A28. 57. Nath A, Venkataramana A, Reich DS, et al. Progression of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy despite treatment with beta-interferon. Neurology 2006;66(1):149Y150. 58. Royal W 3rd, Dupont B, McGuire D, et al. Topotecan in the treatment of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-related progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. J Neurovirol 2003;9(3):411Y419. www.aan.com/continuum Copyright @ American Academy of Neurology. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited. 1391