* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Factors that influence Italian consumers` understanding of over

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

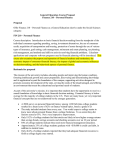

Patient Education and Counseling 87 (2012) 395–401 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Patient Education and Counseling journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/pateducou Medication information Factors that influence Italian consumers’ understanding of over-the-counter medicines and risk perception Andrea Calamusa a, Alessandra Di Marzio a, Renza Cristofani b, Paola Arrighetti c, Vincenzo Santaniello c, Simona Alfani a, Annalaura Carducci a,* a b c Health Communication Observatory, Department of Biology, University of Pisa, Italy Medical Statistics Unit, School of Medicine, University of Pisa, Italy COOP Italia, Italy A R T I C L E I N F O A B S T R A C T Article history: Received 27 April 2011 Received in revised form 11 October 2011 Accepted 22 October 2011 Objective: To evaluate information needs for safe self-medication we explored the Italian consumers’ functional health literacy, specific knowledge and risk awareness about over-the-counter (OTC) medicines. Methods: A survey was conducted in the health sections of six large super stores. Data were collected from a convenience sample of 1.206 adults aged 18 years and older through a self-administered questionnaire. Results: Around 42% confused the concept of ‘‘contraindications’’ with that of ‘‘side effects’’ and were unable to calculate simple dosages. Most respondents were aware of the OTC general potential for side effects but 64.3% did not know that people with high blood pressure should use painkillers with cautions and 14.0% and 20.0% were unaware of the risks of long-term use of laxatives and nasal decongestants respectively. Higher total scores were obtained from women, highly educated people and those citing package leaflets as information sources. Conclusion: The study, the first of this type in Italy, showed an incomplete awareness of several risk areas, with regard to drug interactions and misuse/abuse. Practice implications: The results of this study were the basis of a following intervention plan tailored to the observed consumer needs and including information tools for customers and courses for the retail pharmacists. ß 2011 Elsevier Ireland Ltd. All rights reserved. Keywords: Non-prescription medicines OTC drugs Health literacy Knowledge Risk awareness Information needs 1. Introduction Self-medication is becoming increasingly important, because it offers advantages to healthcare systems in terms of better health outcomes and resource savings and it also impels people towards greater independence in making decisions about their health [1]. Effective self-medication requires that people be able to recognize symptoms and choose the appropriate over-the counter (OTC) medicine, be aware of potential risks, read and follow the instructions in Package Information Leaflets (PILs) and know when to seek the advice of health-care professionals. The decision process of self-medication depends not only on individual knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding health, disease and medication, but also on cultural and social factors. In particular, advertising in different mass media is a potent source of * Corresponding author at: Department of Biology, University of Pisa, via S. Zeno, 35/39, 561127 Pisa, Italy. Tel.: +39 050 2213644; fax: +39 050 2213647. E-mail address: [email protected] (A. Carducci). 0738-3991/$ – see front matter ß 2011 Elsevier Ireland Ltd. All rights reserved. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2011.10.003 information and influence on the purchase and use of OTC medicines. Nevertheless doctors and pharmacists still play a leading role in the self-medication decision-making process, as they are considered the most trustworthy sources of information [2–5]. Although OTC drugs have a favourable safety profile, the relevant risks remain a matter of concern because of the widespread use of these medications. These risks are largely due to some form of inappropriate use [6–14] and may stem from poor knowledge and risk perception [15–17]. Of the several factors that may lead to poor knowledge and low risk awareness regarding self-medication drugs, health literacy can be considered of particular interest: it is a broad complex concept which has been defined as ‘‘the capacity to obtain, process and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions’’ [18], and is strongly related to patients’ knowledge, health behaviors, health outcomes and medical costs [18–20]. Several screening tools have been developed and validated to identify people at risk for poor health literacy and to evaluate its association with medication knowledge [21–25]. However, these tools do not seem to be applicable to large-scale 396 A. Calamusa et al. / Patient Education and Counseling 87 (2012) 395–401 questionnaire surveys, as they cannot be completed easily without help, especially by people with low literacy, defined as scored at level 1 of 5 in prose and document competencies [26]. In the wider concept of health literacy Nutbeam (2000) defined three different levels (functional, communicative and critical): the ‘‘functional health literacy’’ (FHL) represent the baseline literacy individual skills (reading, writing and making simple calculations) that enable people to read and understand health information. The majority of research in clinical settings has focused on FHL, considered as mediating factor in health and clinical decisionmaking [Nutbeam, 2008]. ‘‘To this aim several screening tools (REALM [21,22] TOFHLA [23,24]) have been developed and validated to identify people at risk for poor functional health literacy and to evaluate its association with medication knowledge [25]. In some research studies about clinical conditions such as asthma, hypertension, diabetes, and heart failure, specific aspects of baseline conceptual knowledge have been measured to understand a patient’s learning needs before an educational program. These measures of disease-specific knowledge generally show a direct, linear correlation with measures of reading fluency [19]. As a consequence of the ongoing evolution of OTC distribution across Europe, in Italy since August 2006 all non-prescription medicines, can be sold in channels other than traditional pharmacies, such as supermarket corners, selling also products like herbal remedies, cosmetics etc. In these areas customers can chose medicine by themselves, although the presence of a pharmacist is compulsory at the cash desk to give information and advices. Such a big change in the OTC medicines distribution could lead to an increase of unsafe behaviors if customers are unaware of risks related to self-medication and unable of understanding the information provided by the Package Information Leaflet, that is a leaflet inserted within the outer packaging of the medicinal product containing information about its use and risks (EU Directive 2001/83/EC). In Italy no systematic research has been conducted on health literacy and its association with medication knowledge. The functional literacy of the general adult population as reported by an international study [26,27] is a matter of concern because more than 45% of people aged 16–65 years were scored at the lowest level of prose and document literacy. The aim of this study was to survey Italian consumers’ functional health literacy, specific knowledge and risk awareness about over-the-counter (OTC) medicines, and associated factors. The questionnaire survey was performed at select health sections of Coop, Italian leading company in modern retail, where OTC and health products are sold under the professional supervision of pharmacists. The results of this survey were the first step in designing an information and communication programme focusing on consumer needs. 2. Methods 2.1. Survey design and questionnaire development In a preliminary phase a literature review was carried on PubMed database using the keyword ‘‘self-medication’’. Among the 3880 found references; a further selection was made considering studies about readability and understandability of package leaflets; knowledge; attitudes; perceptios; behaviors and pharmacist counseling. Objectives and methods of these surveys were compared to choose the study design and questions most appropriate for our purpose. A first set of questions exploring the areas of interest for our survey were then asked to a sample of 64 customer attending 8 shopping centres in different cities; using two different methods: semi structured interview (35 people) or self-administered questionnaire (29). The overall response rate was 43% and the most frequent motivation of refusing was the hurry. This preliminary study showed that interviews were time consuming (25 min each) and very difficult; owing to the large turnout of customers: then a self-administered questionnaire (15 min for compilation) was chosen for the survey; although this method could cause a possible selection bias; requiring at least basic reading and writing skills. The first draft of the questionnaire was then tested in 4 focus groups (36 people) and on a convenience sample of 78 university students, in order to fine tune its completeness, readability, comprehensibility and acceptability. A second pilot study, aimed to test the final version of the questionnaire and its distribution method in the real setting, was then carried out on a sample of customers (210) at the health section of the Livorno Coop supermarket [28], a real setting before conducting the large-scale survey. The final questionnaire (available from the authors upon request) consisted of 18 close-ended questions and was divided in 4 sections: (1) Demographic data (age, gender, education), current use of prescription drugs and information sources about minor ailments; (2) Functional health literacy/knowledge section: to measure the ability of reading and understanding information (FHL) related OTC use, a specific new tool was designed, divided in three subsection. The first (vocabulary) investigated the interpretation of most frequent technical words in information leaflet, the second (numeracy) the solution of a simple dosage calculation, the third (knowledge) the awareness about OTC meaning, distribution and identification. (2.1) Vocabulary: 17 high frequency terms were chosen from a list of the most common words obtained through a computational linguistic analysis [29] on a sample of 38 OTC PILs. The understanding of 12 of these terms was tested by asking participants to place them in the correct section of a stylized body divided into four sections (Fig. 1). The meanings of five further terms (‘‘analgesic’’, ‘‘active principle’’, ‘‘dosage’’, ‘‘contraindications’’, ‘‘interactions’’) were asked in multiple-choice questions. (2.2) Numeracy: it was evaluated by asking subjects to calculate the maximum number of pills not to be exceeded per day according to the PILs instructions: ‘‘Take 1 or 2 tablets once or twice a day’’. (2.3) Knowledge of OTC: the synonyms of ‘‘non-prescription medicines’’ were asked, focusing on the possible confusion between OTC and ‘‘generic’’ medicine (i.e. a drug marketed without brand name which is equivalent to a brand reference medicine); moreover the knowledge of OTC distribution channel and identification symbol, which is printed on the outer package of all non-prescription medicines, by national regulations, was tested. (3) Risk awareness: a list of twelve statements representative of three risk categories (‘‘drug interactions’’, ‘‘side effects’’ and ‘‘abuse/misuse’’) was presented for true/false/do not know responses. (4) General attitudes and practices regarding the purchase/use of OTC drugs and PILs: personal motivation for buying OTC drugs, tendency to tell the pharmacist about the concomitant use of other drugs and to read the PIL, PILs understanding and psychological impact were investigated (was the PIL helpful, alarming or confusing?). 2.2. Questionnaire distribution Data were collected from a convenience sample of 1.206 adults aged 18 years and older through a self-administered questionnaire. All questionnaires were collected in the health sections of six Coop large super stores (that include multiple stores, such as a A. Calamusa et al. / Patient Education and Counseling 87 (2012) 395–401 397 Fig. 1. Functional health literacy skills: Knowledge of body location of 12 select terms, definition of 5 select terms and numeracy skill. Participants were asked to place the first 12 terms in the right section of a stylized body divided into four sections. Multiple-choice questions were used to test knowledge of the definition of the other 5 words. The English translations of some of these Italian terms may not adequately reflect their frequency of use in the general population of native English speakers. The plain language translation of technical words is reported following: Cephalea: headache; Gastritis: inflammation of the lining of the stomach; Meniscus: a wedge of cartilage in the knee joint; Oral: to be taken by mouth; Antacid: a substance used to treat acidity in the stomach; Laxative: a medicine that induces the emptying of the bowels; Peptic ulcer: an ulcer in the stomach or duodenum; Mucolytic: an agent that reduces the viscosity of mucus; Hepatic: of the liver; Constipation: a condition in which emptying one’s bowels is difficult; Nephritis: inflammation of the kidney; Hematouria: blood in urine; Analgesic: a drug that relieves pain; Active principle: a constituent of a substance that determines its characteristics; Posology: dosage. The ability to perform simple dosage calculations was assessed by asking participants to calculate the maximum number of pills not to be exceeded per day based on the instructions ‘‘Take 1 or 2 tablets once or twice a day’’. supermarket, a pharmacy, a department store) located in northern (Milan, Turin, Bologna), central (Sarzana, Rome) and southern Italy (Bari). The study was conducted over a five-week period between November and December 2008. The questionnaire was distributed three days a week in each shopping centre, from 10:00 A.M. to 6:00 P.M., on different days of the week (from Monday to Saturday) in order to cover as many customer shopping patterns as possible. A desk, clearly evidenced by posters with the study purpose, was placed at the entrance of each ‘‘health corner’’ (that is the space were OTC are sold in supermarkets). Two trained members of the research team invited to participate every adult customer who entered this area, excluding people evidently vision and cognitively impaired; the purpose of the research was explained and instructions given on how to complete the anonymous questionnaire. The questionnaires were filled out on site and immediately collected in a closed box to guarantee the anonymity. The questionnaire took respondents 15 min on average to complete. No incentive (e.g. discount on purchases) was offered; those who completed the questionnaire received the correct answers as educational feedback. Due to the large turnout of customers in the natural setting of the study, a precise calculation of the response rate was not feasible during the large survey, Then, to estimate the response rate we considered data from pilot tests, when people who refused were asked reason for not participating: as previously reported the overall response rate was 43% and the most frequent motivation of refusing was the hurry. 2.3. Data analysis Except for the age and the number of pills calculation, all answers were coded as qualitative data and entered into Excel for WindowsTM. The spreadsheet was then converted and analysed using the SAS System software (Version 8.2). The relative frequencies of the different answers to each question were calculated, also taking into account missing responses. Participants level of knowledge and risk awareness were evaluated as scores by awarding 1 point for each correct answer, 0.8 for each partially correct answer, 0 for each incorrect, ‘‘do not know’’ or no response. For the vocabulary skills related to the stylized body, a weighted score was attributed to each correct answer depending on the difficulty level of each term as assessed in the pilot studies. The mean total score of the study population and its variability were then calculated, together with the mean knowledge and risk awareness sub-scores. The maximum total score achievable was 27 (15 for the knowledge sub-score and 12 for the risk awareness sub-score). In order to evaluate the influence of information sources we divided the respondents into four sub-groups depending on the sources cited: (1) personal professional sources (doctor and/or pharmacist), alone or associated with other sources, excluding PILs; (2) personal professional sources, alone or associated with other sources, including PILs; (3) non-professional sources, excluding PILs; and (4) non-professional sources, including PILs. Continuous variables were summarized by mean values and standard deviations, the categorical ones by proportions. Pearson’s chi-square test was used to compare categorical variables and the Cochran–Armitage test to evaluate the trend in age or educational in binomial tables. The Student’s t-test was used to compare twosample means and the General Linear Model (GLM) approach to the analysis of variance to simultaneously compare means among levels defined by categorical characteristics of participants. Once a significant difference was found in the analysis of variance, the 398 A. Calamusa et al. / Patient Education and Counseling 87 (2012) 395–401 Bonferroni t test, alfa level = 0.05, was used in multiple comparisons. Spearman correlation coefficient was used to estimate the association among ordinal variables. Lastly, in order to identify the variables most closely associated with correct knowledge and risk awareness, a multiple logistic regression was performed. We decided to use the multiple logistic regression model due to the lack of normality of total score distribution (Shapiro–Wilk W = 0.95, p < 0.0001; Kolmgorov–Smirnov D = 0.085, p < 0.01). To this aim, the total score was divided into two levels (<21 and = or > 21 based on its median value), the education into two categories (primary/middle and secondary/degree) and the age into four classes: 18–29, 30–44, 45– 59 and the last 60 years which was taken as reference in the logistic analysis. Probability of alpha levels less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Sas software, version 8.2, has been used for all statistical computations. 3. Results 3.1. Sample characteristics On the whole, 1.206 questionnaires were collected. The participants’ characteristics are shown in Table 1. About 44% professed to take prescription medicines regularly, without gender difference, but with a positive age related trend (Cochran– Armitage trend test: z = 12.95, p < 0.0001), and a significant association with the education level (Cochran–Armitage trend test: z = 7.0, p < 0.0001), indicating an higher use of prescriptions in people with lower education levels. 3.2. Information sources about minor ailment remedies The most frequently cited information sources were personal ones (61.5% doctor, 40.4% pharmacist, 26.5% friends/relatives); 4.5% declared that they did not use any source of information, but decided on their own. Written and mass-media sources were less commonly mentioned (16.5% PIL, 8.6% journals/magazines, 8.5% internet, 7.5% television, 4.5% advertising). Regarding the professional sources (doctor and/or pharmacist), females were more likely to cite them than males (81.6% vs 74.3%, p < 0.005), while there was no difference in terms of age or education or prescription drug use. PIL was less frequently cited by males than females (12.5% vs 19.6%, p < 0.01), by those aged 60 than other age groups (9.8% vs 19.3%, p < 0.001), by those with lower education (primary/ middle) than those with higher education (secondary/degree; 11.1% vs 18.3%, p < 0.01) and by prescription drug users than nonusers (13.0% vs 18.8%, p < 0.01). 3.3. Health literacy, knowledge and risk awareness The knowledge and risk awareness sections were filled out to at least 80% by 1.061 respondents (88% of the study sample): for the analysis regarding these aspects we used data from the respondents who completed all sections of the questionnaire. The literacy skills results are shown in Fig. 1: correct body placement varied from 90.0% for ‘‘cephalea’’ to 28.3% for ‘‘haematuria’’. A lexical confusion between the concepts of drug contraindications and side effects was found in 30% of respondents. More than half of participants gave the correct answer to the numeracy test, with a significant association with education level (82% secondary/ degree vs 18% primary/middle, p < .0001). Among the wrong answers, the lower dosage predominated (34.2% against 4.4%). Almost half of respondents gave the correct answer about the meaning of ‘‘non-prescription’’ medicines, but 41.7% confused them with ‘‘generic’’ drugs. Only 61.4% of the respondents recognized the OTC identification symbol. Most respondents knew that only non-prescription drugs can be sold in supermarkets. Table 1 Background characteristics of Italian health section clients of a retail chain participating in the study (total = 1.206). Gender (n = 1.145) Female Male Age (n = 1.145) 18–29 years 30–44 years 45–59 years 60 Education (n = 1.145) Primary (grades 1–5) Middle (grades 6–8) Secondary (grades 9–13) University degree Use of prescription drugs (n = 1.146) Yes No Information sources (n = 1.198)* Group 1a Group 2b Group 3c Group 4d * a N (%) 637 508 (55.6) (44.4) 109 347 337 352 (9.5) (30.3) (29.4) (30.7) 80 238 590 237 (7.0) (20.8) (51.5) (20.7) 510 636 (44.5) (55.5) 794 148 205 51 (66.3) (12.3) (17.1) (4.3) Participants were divided into four groups depending on stated sources. Group 1: professional sources, alone or associated with other sources, excluding PIL. b Group 2: professional sources, alone or associated with other sources, including PIL. c d Group 3: non-professional sources, excluding PIL. Group 4: non-professional sources, including PIL. The results of the risk awareness section are shown in Fig. 2. Most respondents were aware of the risks related to OTC drugs’ potential for side effects. On the other hand, the drug interaction risk category revealed the highest percentage of incorrect and ‘‘do not know’’ responses, in particular about the risk of using painkillers for people suffering from high blood pressure. With regard to the misuse/abuse risk category, 14 and 20% of respondents showed inadequate awareness of the risks related to the long-term use of laxatives and nasal decongestants, respectively. The scores for knowledge and risk awareness are presented in Table 2. The mean total score was 20.12 (SD 4.15, range 2.00– 27.00). Scores were directly associated with female gender and education level. Moreover, the middle age groups between 30 and 59 years achieved higher mean totals than younger and older groups. Similar associations were found for the mean knowledge and risk awareness sub-scores. No significant differences were found between prescription drug users and non-users for mean total score or the two mean subscores. The subgroups citing PILs as information source had significantly higher mean knowledge and total scores. Those who cited nonprofessional sources without doctor or pharmacist, but included PILs among their sources had significantly higher knowledge and total scores, while there was no significant difference between the subgroups for the risk awareness sub-score. These results were confirmed by multiple logistic regression. Higher total scores were directly associated with higher education level (OR 2.9; 95% CI 2.1–4.1), female gender (OR 1.8; 95% CI 1.4–2.4) and the citation of PILs among the information sources (OR 1.7; 95% CI 1.2–2.5). Regarding age, the oldest one taken as reference, adults aged between 45 and 60 years had significantly higher total scores (OR 1.7; 95% CI 1.2– 2.4) and young aged between 18 and 25 years significantly lower (OR 0.3; 95% CI 0.2–0.5). The correlation between functional health literacy and risk awareness sub-scores was slightly positive (Spearman correlation coefficient 0.38). A. Calamusa et al. / Patient Education and Counseling 87 (2012) 395–401 Correct Incorrect "I don't know" 399 Missing DRUG INTERACTIONS It's better to tell the pharmacist if you are taking other medication If taken together, two painkillers work better Non-prescription drugs may not "agree with" with other drugs Those who suffer from high blood pressure should use painkillers with caution MISUSE/ABUSE It's important to consider children's weight before giving them drugs Laxative drugs, if used regularly to lose weight, are potentially harmful Long-term use of nasal decongestants is potentially harmful Those who suffer from constipation must take laxative drugs regularly SIDE EFFECTS Even non-prescription drugs may cause side effects Painkillers may damage the stomach A drug promoted through advertising is safer Some drugs against allergies may cause sleepiness 0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100% Fig. 2. Perception of risks associated with OTC drug use, according to three risk categories: drug interactions, misuse/abuse, side effects. Participants were asked to indicate whether each statement was true or false; the option ‘‘do not know’’ was also included. The results are presented as correct answers regardless of whether true or false. 3.4. Attitudes and practices regarding the purchase and use of OTC drugs and package leaflets Only 39.8% of the sample declared telling their pharmacist that they take other drugs at the time of purchase, with no difference between prescription drug users and non-users. Most respondents reported that they read PIL every time they buy an OTC medication, mainly regarding the dosage instructions and side effects, but only 38.1% professed to completely understand their contents, with significant differences between education levels (46.1% for secondary/degree versus 26.0% for primary/middle p < .0001). The impact of reading the package leaflets was reportedly Table 2 Participant characteristics associated with knowledge (the maximum score was 15), risk awareness (the maximum score was 12) and total mean scores (the maximum achievable total score was 27). Knowledge sub-score Risk awareness sub-score Mean Total score Characteristic Mean SD p value SD p value Mean SD p value Total sample Gender Male Female Age 18–29 years 30–44 years 45–59 years 60 years Education Primary (grades 1–5) Middle (grades 6–8) Secondary (grades 9–13) University degree Use of prescription drugs Yes No Information sources* Group 1a Group 2b Group 3c Group 4d 10.38 3.02 – 9.60 2.06 – 20.12 4.15 – 9.99 10.79 2.96 2.98 <.0001 9.34 9.85 2.15 1.87 <.0001 19.40 20.82 4.10 3.96 <.0001 9.33 10.93 10.99 9.62 2.77 2.74 2.91 3.23 <.0001 8.96 9.71 9.93 9.48 1.96 1.82 1.88 2.24 <.0001 18.38 20.67 21.01 19.35 3.97 3.90 3.91 4.23 <.0001 7.63 9.09 10.53 12.01 3.25 2.99 2.86 2.22 <.0001 9.01 9.45 9.62 10.05 2.37 2.20 1.97 1.72 0.0002 17.09 18.70 20.22 22.09 4.22 4.23 3.98 3.23 <.0001 10.27 10.51 3.15 2.93 0.22 9.52 9.71 2.15 1.89 0.10 19.94 20.31 4.27 4.01 0.16 10.27 11.28 10.09 10.65 3.08 2.68 2.94 2.98 0.002 9.59 9.80 9.49 9.82 2.04 1.95 2.15 2.00 0.43 19.96 21.27 19.77 20.74 4.17 3.97 4.11 3.98 0.003 Note: Total score, knowledge and risk awareness sub-scores were calculated for each respondent by awarding assigning 1 point for each correct answer, 0.8 for each partially correct answer, 0 for each incorrect, ‘‘do not know’’ or no answer. The mean scores are associated to gender, age groups, education levels, use of prescription drugs and information sources on minor ailment remedies The mean total score of the study population and its variability was then calculated, together with the mean knowledge and risk awareness sub-scores. p values are the probabilities of an alfa error as defined by Anova analysis. * Participants were divided into four groups depending on stated sources. a Group 1: professional sources, alone or associated with other sources, excluding PIL. b Group 2: professional sources, alone or associated with other sources, including PIL. c Group 3: non-professional sources, excluding PIL. d Group 4: non-professional sources, including PIL. 400 A. Calamusa et al. / Patient Education and Counseling 87 (2012) 395–401 perceived as helpful by 67.3% of respondents, but as alarming by 22.6% and as confusing by 9.2%. 4. Discussion and conclusion 4.1. Discussion This study was intended to explore the consumers’ functional health literacy, specific knowledge and risk awareness about overthe-counter (OTC) medicines in order to develop an educational program tailored to the real information needs. The results of this study are in line with other surveys which point to the doctor and the pharmacist as the public’s main sources of information on general health matters and on drug usage, women being more likely to choose personal professional sources than men [2–5,32,33]. Regarding information needs, the mean score resulting from the study revealed that the majority of respondents have a good knowledge and risk awareness related to OTC drugs. As reported in previous studies [25,30], functional health literacy, including vocabulary, reading and numeracy skill, is directly associated with education level, age and female gender. However, a better understanding of the information could be obtained by using plain language, glossaries and clear explanations. Although European Directive [31] dictates that PILs must be written and designed to be clear and understandable, and Italian national regulations [32] require that terms such as ‘‘contraindications’’, ‘‘active principle’’ and ‘‘dosage’’ are to be substituted by standard explanatory wordings, a difficult language is still present in several national OTC PILs (as revealed by the analysis of 38 PILs). Also the results about the numeracy skills showed that quantitative dosage instructions can be misinterpreted and, as other studies suggest [33], it is essential to optimize dosage instructions in PILs and to specify the maximum number of pills not to be exceeded per day. Although the level of risk awareness is generally high, between 10 and 65% of respondents are not fully aware of several risk areas, particularly regarding drug interactions and misuse/abuse. These results show that OTC risk awareness should be increased in the general public, as indicated in previous studies [4,14,17]. Our study reveals that prescription drug users do not show a higher drug interaction risk awareness in comparison to non-users, neither a more positive attitude in informing a pharmacist of the concomitant use of other drugs. Although in our study most people showed to be aware of the potential gastric damage of OTC NSAIDs, another fairly common risk condition, such as the concomitant use of these drugs and antihypertensive prescription medicines, is scarcely known. Furthermore up to 22% of respondents are unaware of OTC misuse risks, e.g. long-term use of laxatives and nasal decongestants. Even the rising trend in OTC abuse, such as the long-term use of laxatives to lose weight, should be deepened in future studies, as also suggested in other studies [4,11]. Higher education, female gender, adult age (44–60 years) and the citation of PIL and non-professional information sources are independent variables predictive of higher total scores. As well as the oldest age 60 years, the youngest age class (18–29 years) is associated to the probability to have lower scores. The results on information sources are in line with other surveys which point to doctors and pharmacists as the public’s main sources on general health matters and on drug usage, women being more likely to choose personal professional sources than men [2–5,34,35]. Regarding the package leaflet, although there is a general positive attitude towards its consultation, this study shows that, while the vast majority declared they could read it, less than half said they understood it in accordance with a research published in 2000 [36]. Nevertheless this study suggests that the PIL may be an important factor affecting knowledge and risk awareness as respondents who cited PIL among information sources had significantly higher knowledge scores. Some limitations in the present study must be considered when interpreting the data. Potential selection bias can be due to questionnaire distribution: the self-compilation probably excluded people unable to read or vision impaired. For this reason the sample had an education level higher than expected on the basis of national data. Besides, excluding Sunday from the questionnaire distribution could have also excluded people who work weekdays. In fact probably the study has overestimated the general public’s knowledge and risk awareness. Besides not all critical issues related to OTC medicines could be covered in the questionnaire. We tried to focus on a mix of knowledge, skills and awareness that can foster consumer wisdom and responsibility in choosing and using OTC drugs. 4.2. Conclusion The present study is the first to explore functional health literacy regarding OTC medicines in a sample of Italian consumers. The results show gaps in understanding the vocabulary of package leaflets and in the ability to calculate maximum daily dosages, as well as a low awareness of risk, mostly related to drug interactions and misuse/abuse. The OTC marketplace is still evolving, and with it, the knowledge and risk awareness of the general public. Further studies will therefore be essential in order to monitor the public’s growing need for information on self-medication. An all-out effort is moreover required to increase public’s knowledge and risk awareness of potential side effects, drug interactions and misuse/abuse. Our results indicated that all consumers, regardless of their literacy skills, need to be educated about OTC medicines and their risks. Educational programmes should address both a pharmacist-assisted self-care model and written information materials, which must contain scientifically reliable information presented in a form that is easily understandable, acceptable and useful to consumers. 4.3. Practice implications The results of this study have implications for both health professional-patient communication regarding the risks of OTC medications and the development of educational programmes tailored to consumer information needs. Following the data analysis, we developed an intervention plan, including information tools for customers, available at supermarket health sections and on the retailer’s Website [37]. The intervention plan also included meetings with the retailer’s pharmacists in order to sensitise them to the results of the study and their key role in meeting OTC consumers’ information needs. From a methodological perspective the next step is to test the questionnaire further in comparison to standardised health literacy screening tools, such as REALM, and transfer the method to other functional health literacy areas to guide the development of educational programmes. Acknowledgements The study was co-funded by Coop and the University of Pisa. No ethical approval was required. The authors would like to thank the management, pharmacists, members and clients of Coop sites for their co-operation during the study. A. Calamusa et al. / Patient Education and Counseling 87 (2012) 395–401 References [1] Hughes CM, McElnay JC, Fleming GF. Benefits and risks of self medication. Drug Saf 2001;24:1027–37. [2] Eurobarometer 58.0 (Spadaro R.). European Union citizens and sources of information about health. The European Opinion Research Group (for Directorate-General Sanco). Available from: http://ec.europa.eu/health/ ph_information/documents/eb_58_en.pdf; March 2003 [accessed July 2010]. [3] Nahri U, Helakorpi S. Sources of medicine information in Finland. Health Policy 2007;84:51–7. [4] Wazaify M, Shields E, Hughes CM, McElnay JC. Societal perspectives on overthe-counter (OTC) medicines. Fam Pract 2005;22:170–6. [5] Censis Forum per la Ricerca Biomedica. Trent’anni di ricerca biomedica e di lotta alle malattie: passato e future del farmaco. Roma; 15 Ottobre 2008. [6] Ferris DG, Nyirjesy P, Sobel JD. Over-the-counter antifungal drug misuse associated with patient-diagnosed vulvovaginal candidiasis. Obstet Gynecol 2002;99:419–25. [7] Grigoryan L, Burgerhof JG, Haaijer-Ruskamp FM, Degener JE, Deschepper R, Monnet DL, et al. Is self-medication with antibiotics in Europe driven by prescribed use? J Antimicrob Chemother 2007;59:152–6. [8] De Bolle L, Mehuys E, Adriaens E, Remon JP, Van Bortel L, Christiaens T. Home medication cabinets and self-medication: a source of potential health threats? Ann Pharmacother 2008;42:572–9. [9] Heard K, Sloss D, Weber S, Dart RC. Overuse of over-the-counter analgesics by emergency department patients. Ann Emerg Med 2006;48:315–8. [10] Wazaify M, Kennedy S, Hughes CM, McElnay JC. Prevalence of over-thecounter drug-related overdoses at accident and emergency departments in Northern Ireland–a retrospective evaluation. J Clin Pharm Ther 2005;30: 39–44. [11] Hughes GF. Abuse/misuse of non-prescription drugs. Pharm World Sci 1999;21:251–5. [12] Steinman KJ. High school students’ misuse of over-the-counter drugs: a population-based study in an urban county. Adolesc Health 2006;38:445–7. [13] Sihvo S, Klaukka T, Martikainen J, Hemminki E. Frequency of daily over-thecounter drug use and potential clinically significant over-the-counter-prescription drug interactions in the Finnish adult population. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2000;56:495–9. [14] Indermitte J, Reber D, Beutler M, Bruppacher R, Hersberger E. Prevalence patient awareness of selected potential drug interactions with self-medication. J Clin Pharm Ther 2007;32:149–59. [15] Shi CW, Asch SM, Fielder E, Gelberg L, Nichol MB. Consumer knowledge of over-the-counter phenazopyridine. Ann Fam Med 2004;2:240–4. [16] Hughes L, Whittlesea C, Luscombe D. Patients’ knowledge and perception of side-effects of PTC medication. J Clin Pharm Ther 2002;27:243–8. [17] Wilcox CM, Cryer B, Triadafilopoulos G. Patterns of use and public perception of over-the-counter pain relievers: focus on nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. J Rheumatol 2005;32:2218–24. [18] Institute of Medicine. Health literacy: a prescription to end confusion. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2004. [19] Baker DW. The meaning and the measure of health literacy. J Intern Med 2006;21:878–83. 401 [20] Clement S, Ibrahim S, Crichton N, Wolf M, Rowlands G. Complex interventions to improve the health of people with limited literacy: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns 2009;75:340–51. [21] Davis TC, Long SW, Jackson RH, Mayeaux EJ, George RB, Murphy PW, et al. Rapid estimate of adult literacy in medicine: a shortened screening instrument. Fam Med 1993;25:391–5. [22] Arozullah AM, Yarnold PR, Bennett CL, Soltysik RC, Wolf MS, Ferreira RM, et al. Development and validation of a short-form, rapid estimate of adult literacy in medicine. Medical Care 2007;45:1026–33. [23] Baker DW, Williams MV, Parker RM, Gazmararian JA, Nurss J. Development of a brief test to measure functional health literacy. Patient Educ Couns 1999;38:33–42. [24] Parker RM, Baker DW, Williams MV, Nurss JR. The test of functional health literacy in adults (TOFHLA): a new instrument for measuring patient’s literacy skills. J Gen Intern Med 1995;10:537–42. [25] Marks JR, Schectman JM, Groninger H, Plews-Ogan ML. The association of health literacy and socio-demographic factors with medication knowledge. Patient Educ Couns 2010;78:372–6. [26] Learning a living first results of the adult literacy and life skills survey – statistics canada and organisation for economic co-operation and development; 2006. [27] Saverio Avveduto Volar senz’ali. Roma: I.P.S.; 2004. [28] Calamusa A, Carducci A, Di Marzio A, Cristofani R, Arrighetti P, Santaniello V. Swallowed drugs or reasoned drugs? Communication and information needs of the customer/consumer attending the health corners Coop–results of the pilot study. In: 2008 International Conference on Communication in Health (Oslo, 2–5/9/2008); 2008. [29] DBT (DataBase Testuale). Computational linguistic software developed at CNR (Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche) of Pisa (Dr. Eugenio Picchi); 2000. [30] Kripalani S, Henderson LE, Chiu EY, Robertson R, Kolm P, Jacobson TA. Predictors of medication self-management skill in a low-literacy population. J Gen Intern Med 2006;21:852–6. [31] European Directive 2001/83/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 6 November 2001 on the Community Code relating to medicinal products for human use. Available from: http://eurlex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CONSLEG:2001L0083:20070126:en:PDF; [accessed July 2010]. [32] Circolare 16 Ottobre 1997, n. 13 Medicinali di automedicazione: definizione, classificazione e modello di foglio illustrativo. Available from: http:// www.normativasanitaria.it/jsp/dettaglio.jsp?id=20548; [accessed July 2010]. [33] Fuchs J, Hippius M. Inappropriate dosage instructions in package inserts. Patient Educ Couns 2007;67:157–68. [34] Bernardini C, Ambrogi V, Perioli L. Drugs and non-medical products sold in pharmacy: information and advertising. Pharmacol Res 2003;47:501–8. [35] Gfk Eurisko per ANIFA (Associazione Nazionale dell’Industria Farmaceutica dell’Automedicazione) – Federchimica. Osservatorio sull’Automedicazione. Rapporto 2008. available from: http://www.sefap.it/servizi_letteraturacardio_200807/ANIFA_rapporto2008.pdf; [accessed July 2010]. [36] Bernardini C, Ambrogi V, Perioli L, Tiralti MC, Fardella G. Comprehensibility of the package leaflets of all medicinal products for human use: a questionnaire survey about the use of symbols and pictograms. Pharmacol Res 2000;41:679–88. [37] Coop Salute website. Available from: http://www.ecoop.it/portalWeb/portlets/ coopSalu te/coop Sal ute.portal; jsess io nid =Qs KM LK kds gh Jy j93vDcZyzlp1rWCczcHpGrYy0KcBVKkhXhG2p6S!-1241226024; [accessed June 2010].