* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Companies, Not Countries

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

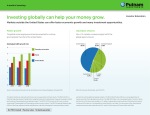

Companies, Not Countries The Real Opportunity in Emerging Markets The Allure of Emerging Markets For decades, the promise of emerging stock markets has fascinated and attracted investors. Despite chronic volatility and, at times, breathtaking market plunges, the “rising tide” of economic growth in developing countries has been a compelling story. With economists predicting that growth in developing countries could outpace that of developed economies by as much as 200%–300% over the next several decades, that story is more compelling than ever (Display 1). Not only are return expectations higher, but many of the high-risk elements of emerging markets appear to be diminishing. In the past, emerging countries were rife with fiscal and monetary mismanagement, significantly contributing to their recurring growing pains. But over the last decade or so, a wave of structural reforms has swept across much of the developing world, and emerging market fundamentals have Display 1 Expectations for Future Emerging Markets Economic Growth Are High Projected* Real GDP Growth SUMMARY The conventional investment wisdom of “going where the growth is” would suggest increasing equity allocations to emerging markets. But our research shows that there’s little relationship between countrylevel GDP growth and local stock market returns. The best way to take advantage of the developing world’s growth is through bottom-up research that identifies companies that are most likely to benefit and that are priced attractively. 2007–2050 (USD) 10 8 Percent 6 Emerging Avg. 5.6% 4 2 Developed Avg. 2.0% 0 n Japa y an Germ Italy UK ce Fran n Spai US da Cana ralia Aust a re S. Ko nd Pola ia Russ ico Mex rica S. Af ntina Arge y Turke il Braz land Thai a ysi Mala stan Paki sia ne Indo a Chin t Egyp nes ppi Phili India Historical analysis and current estimates do not guarantee future results. *Projections from PricewaterhouseCoopers, March 2008 Source: John Hawksworth and Gordon Cookson, The World in 2050: Beyond the BRICs, PricewaterhouseCoopers, March 2008 MARCH 2010 Display 2 There Are Good Reasons to Believe that Growth Is Sustainable Emerging Markets Current Account Emerging Markets Foreign Currency Reserves USD Billions USD Trillions 1,000 6 800 5 600 4 400 3 200 2 0 1 98 09E Percent 45 40 35 30 25 0 (200) Emerging Markets External Debt to GDP 20 99 09 98 02 06 10E As of January 22, 2009 Historical analysis and current estimates do not guarantee future results. Data, including estimates through 2009, are subject to change. Source: International Financial Statistics (IFS), International Monetary Fund (IMF), and World Economic Outlook (October 2009) Do rising GDP estimates and more favorable risk factors signal the opportunity of a lifetime for investors? The common investment wisdom of “going where the growth is” would suggest increasing equity allocations to emerging markets—and that is exactly what investors have been doing (Display 3). From 2005 through 2009, US investors poured more money into emerging markets equity funds than into US funds, with about 40% of the flows going to single-country or target group funds, such as the so-called BRIC countries: Brazil, Russia, India, and China.1 But our research suggests caution. Simply allocating more of one’s portfolio to growing markets (whether emerging or developed) fails to take into account an important but often overlooked truth: that typically there is no direct relationship between a country’s GDP growth rate and investor returns. While the developing world will likely continue to expand its share of the global economy as well as of the world equity markets, this shift does not in and of itself guarantee outsized returns for investors in emerging markets stocks. pursue individual securities in emerging markets. Second, it creates opportunities for companies of all nationalities to participate in the growth. Identifying the best performers among those companies, regardless of their home base, is the key to benefiting from emerging markets growth. In other words, investors shouldn’t simply “go where the growth is”—they should go where the profit growth is. And remember, the maturation of the emerging markets does not negate the need for vigilance toward risk. Avoiding over-concentration in a single country, industry, or stock is still vitally important. Display 3 Investors Believe the Story Emerging Markets Fund Flows Relative to US Fund Flows 1994–2009 90 60 30 USD Billions strengthened dramatically. As Display 2 shows, current accounts have moved from deficits to surpluses; currencies are stronger; and formerly heavy debt burdens have been greatly reduced. 0 (30) (60) (90) (120) However, the maturation of the developing world does present a wealth of opportunity in two important respects: First, with the lowering of country-specific risks, investors are freer to Source: Lipper, Strategic Insight, and AllianceBernstein 1 2 Companies, Not Countries: The Real Opportunity in Emerging Markets 94 95 96 97 98 99 00 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 Through December 31, 2009 Source: Lipper, Strategic Insight, and AllianceBernstein Display 4 The Link Between GDP Growth and Stock Market Returns In the US, Long-Term Stock Market Growth Has Tracked the Economy Why doesn’t GDP growth automatically translate into investor returns? It would seem to be intuitive: Stock values, after all, reflect corporate profit growth over time, which is a key factor of GDP growth. In the US, for example, there is a clear longterm relationship between GDP growth and stock market returns since World War II, as seen in Display 4. Annualized Growth Rates 1948–2009 S&P 500 Price US GDP* S&P 500 Operating Earnings† 48 54 61 68 7.2% 6.7 6.1 75 82 89 96 03 09E As of December 31, 2009 Past performance does not guarantee future results. *Actual GDP through December 31, 2008; 2009 GDP estimate by AllianceBernstein as of December 31, 2009 †Actual earnings through December 31, 2008; 2009 consensus estimate as of December 31, 2009 Source: FactSet, Standard & Poor’s, Thomson First Call, US Bureau of Economic Analysis, and AllianceBernstein But there is also a lot of volatility in the relationship along the way. As the display shows, stock market returns can “de-link” from GDP growth for long periods of time. In fact, over the most recent 20-year period, there is effectively no relationship between GDP growth and long-term investor returns on a local country basis in either the developed or emerging markets (Displays 5 and 6).2 To stress-test these results, we also looked at each five-year period. (See Appendices 1 and 2, pages 8–9). The results were the same. Display 5 But the Relationship Between Market Growth and the Economy Doesn’t Hold Elsewhere… Display 6 …Particularly in the Emerging Markets 20 Years Ending December 2009† 8 12 6 8 4 4 2 0 0 (4) 8 16 6 12 4 8 2 4 0 0 a Brazil pines Philip n Jorda tin Argen o Rea l Per Capita GDP Growth Mexic Turkey nd Thaila e sia Malay esia Indon al Portug Chile Total Equity Return 20 Greec Japan en Swed d Finlan land ea New Z Italy lia Austra France nd rla Switze dom d King Unite Kong Hong any Germ Austria ark Denm m Belgiu ds rlan Nethe Spain ay Norw pore Singa Real Per Capita GDP Growth *All countries categorized as Developed by MSCI as of January 1990 †All values annualized; nominal stock market returns; (R2)=0.11; see definition of R2, pg. 8. Source: International Finance Corporation (IFC), IMF, and Morgan Stanley Capital International (MSCI) 10 Equity Return, USD (%) 16 Equity Return, USD (%) 10 GDP Growth (%) Emerging Markets* Real Per Capita GDP Growth vs. Stock Market Returns 20 Years Ending December 2009† GDP Growth (%) Developed Markets* Real Per Capita GDP Growth vs. Stock Market Returns Total Equity Return *All countries categorized as Emerging by MSCI as of January 1990 †All values annualized; nominal stock market returns; (R2)=0.02; see definition of R2, pg. 8. Source: IFC, IMF, and MSCI Here we show a comparison of per capita GDP growth to stock market returns, but the conclusion also holds for total GDP growth, which includes growth driven solely by population expansion. 2 3 Where Do Equity Returns Come From? Total return—for all markets, not just emerging markets— comes from three components: the return from dividends, the return from changes in the price/earnings (P/E) multiple, and earnings-per-share (EPS) growth. Only one component, EPS growth, is relevant when considering how economic growth may affect shareholder returns. That’s because corporate earnings (the “E” in EPS) are directly related to economic growth, while dividend yield and changes to the P/E multiple have tenuous links at best. Let’s look at each in turn: n n n Dividend yield, defined as cash payments to investors scaled by the price paid per share, is highly idiosyncratic, as it is determined by a company’s directors. Clearly, investors are not pouring money into emerging markets because they think there will be a systemic change in dividend policy. The P/E multiple is determined by the company’s current stock price as much as it is by earnings. Changes in the P/E multiple are primarily an indicator of investors’ perceptions about changes in the future earnings growth rate. If investors believe that the emerging markets will grow faster than current expectations, some P/E expansion might be expected. Earnings per share is the component most directly related to economic growth—at least to the extent that a rising GDP tide will “lift all boats” as local companies benefit from increasing economic activity. However, even this relationship is not as direct as one might expect, as we will see. Why isn’t there a closer link between EPS and GDP? Because the connection is too tenuous. Think of it like a leaky water pipe: Even if GDP is gushing into the pipe, what emerges at the other end is a calm stream. Display 8 (following page) illustrates the sources of leakage. Who benefits from a nation’s GDP growth? Broadly, government (via taxes and state-owned enterprises, for example), labor (via personal consumption and investment), and corporations, as shown in the left bar of Display 8. Stock market investors can’t invest directly in government or labor, so some of the GDP growth gets diverted from EPS growth here. Corporations, in turn, fall into categories: private and public enterprises, as shown in the middle bar. Since the great majority of investors invest only in publicly traded companies, we can strip out the private enterprises. So, the share of earnings going to the stock market depends on—among other things—the extent of government’s involvement in business and the bargaining power of labor, as well as the relative growth of public versus private business. The relative impact of all these factors varies greatly from country to country. Display 7 The Link Between GDP Growth and EPS Growth Is Weak Per Capita GDP Growth vs. EPS Growth* MSCI Emerging Markets EPS (1993–2009) 20 EPS Growth (%) Why isn’t the relationship between GDP growth and long-term investor returns more reliable? For insight, let’s break down the sources of equity returns. Argentina 10 R2=0.23 0 China (10) (20) 0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 Per Capita GDP Growth (%) The Weak Link Between GDP and EPS As Display 7 indicates, the historical relationship between economic growth and EPS growth in the emerging markets—even after discounting the effects of significant outliers— is not particularly strong. In fact, a striking outlier is China, arguably the most exciting GDP growth story of the past 15 years, where the EPS growth has been negative: (3)% per annum. 4 Companies, Not Countries: The Real Opportunity in Emerging Markets All countries categorized as Emerging by MSCI as of January 1990 *Real per capita GDP growth; countries with more than 12 years of EPS data; R2=0.23 excluding China and Argentina; R2=0.01 including China and Argentina; see definition of R2, pg. 8, and Appendices 3 and 4 for data. Source: IMF, MSCI, and AllianceBernstein Last but not least, the right-hand bar shows a final “leak” from the pipeline: Public company earnings can be divided into the portion captured by new share issues and the portion tied to already existing shares. Only the existing shares, by definition, determine EPS growth. Further, new shares dilute the value of existing shares. The impact of equity issuance is especially pronounced in the emerging markets, where a large number of companies have migrated to the public markets since the late 1980s, and we can reasonably assume they will continue to do Display 8 The Link Between GDP and EPS Is Tenuous Hypothetical Path from GDP to EPS so as the markets grow. As Display 9 shows, the expansion in the number of listed public companies has accounted for an increase of more than 21% in aggregate earnings of publicly traded companies per year over the past two decades, and an increase in total emerging markets capitalization of almost 25% annually. The Chinese experience highlights yet another important, though often overlooked, disconnect in the GDP-to-EPS growth pipeline. Globalization encourages firms around the world to allocate portions of their investments and operations into foreign countries, often attracted by cheap labor. For China, this has meant large inflows of foreign direct investment and a rising share of total Chinese exports produced by foreignrelated firms (Display 10). Gov’t Labor Private Public Corp. Profits Corporate Profits GDP New Issuances Existing Shares Local Stock Market Source: AllianceBernstein While this aspect of China’s economy, like that of many other developing nations, may benefit the country and its overall growth, it does not necessarily translate into a competitive advantage for Chinese companies, thus further clouding the link between GDP growth and EPS growth. On the contrary, it suggests that the rise of developing world economies may have as profound an impact on companies based in developed nations as it does on emerging markets companies themselves. Display 10 Foreign-Related Firms Produce More than Half of Chinese Exports New-Share Issuance Further Weakens GDP-EPS Link Impact of New Shares on Total Returns Percent Percent 24.9 21.4 12.7 10.8 7.8 7.1 9.7 8.4 Exports of Foreign Firms in China 1,600 80 1,200 60 800 40 400 20 0 0 96 97 98 99 00 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 Foreign Developed Emerging Aggregate Earnings Growth EPS Growth Developed Emerging Market Cap Growth Total Return Total Shares of Foreign Affiliates (%) Impact of New Shares on EPS Exports (USD Billions) Display 9 Percent As of November 30, 2009 Source: CEIC Data, Chinese Ministry of Foreign Trade and Economic Cooperation, and United Nations Conference on Trade and Development December 1987 through April 2008, annualized USD Source: MSCI, Standard & Poor’s/IFC, and AllianceBernstein 5 Indeed, in a world where companies and markets operate across national borders, ultimately it is global economic growth—not the growth of the country or market where a given company is domiciled—that determines the parameters of global EPS growth. one had to contend with the ever-present possibility of being “right about the company but wrong about the country.” Concerned about country risk, many investors avoided exposure to the emerging markets altogether. The weak link between a country’s GDP growth and the EPS growth of companies domiciled there suggests that investors should not expect a free ride simply by investing passively in a fast-growing economy. As we discuss in the next section, however, the globalization process does create the potential for higher returns by expanding the universe of publicly traded companies that may benefit from the rise of the world’s developing economies. Those who invested in emerging markets often did so for diversification purposes. For many years, emerging markets equities traded in highly segmented markets, each with unique return potential and risks. The idiosyncratic nature of these risks tended to dampen short-term correlations with both developed markets and other emerging markets, providing valuable portfolio diversification benefits. Today, however, the diversification benefit is smaller as correlations between the emerging and developed world have increased (Display 11). Globalization has, in effect, created greater linkages between countries, causing the world’s stock markets to move more closely together. Some would go so far as to argue that once you combine the higher historical volatility of the emerging markets with the now-higher correlation with the developed world, emerging markets should be removed from investor portfolios. How Investors Can Benefit from Emerging Markets GDP Growth Over the past 15 to 20 years, the pace of market openings and reforms has increased dramatically across the developing world, leading not only to new investment opportunities but also to a more attractive environment for investors. Prior to the late 1980s and early 1990s, a vast array of constraints, both practical and regulatory, kept most emerging equity markets largely closed to foreign investment. So-called country risk was an ever-present danger, whether in the form of political instability, corruption, or other intrinsic problems. In the past, However, a side effect of this rising correlation is that the country-level risk has decreased substantially as a driver of the investment decision (Display 12). So, while idiosyncratic country risk remains, the percentage of an individual stock’s return that Display 11 Display 12 The Correlation Between the Emerging Markets and the Developed World Has Been Rising Country-Specific Risk Factors Have Diminished as Markets Globalize Correlation of Emerging Market Returns to Developed Market Returns Percent of Individual Stock Variance Explained by Country of Domicile Five-Year Rolling Periods, 2000–2009 100 Emerging: Developed: 90 26.5% 16.3% 30 Percent 95 Percent 40 Annualized Volatility 1996–2009 85 80 10 75 0 70 00 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 Through December 31, 2009 Past performance does not guarantee future results. Source: MSCI and AllianceBernstein 6 20 Companies, Not Countries: The Real Opportunity in Emerging Markets 09 93 95 97 99 Through December 31, 2009 Source: MSCI and AllianceBernstein 01 03 05 07 09 is attributable to its country of domicile has declined dramatically. Thus, to minimize risk, an investor should search across the widest possible opportunity set to find the best investment opportunities and control risk through prudent diversification across industries, sectors—and countries. As active managers, we look for dispersion in the investment opportunity set in order to find companies that are positioned to outperform. For example, while consensus economic forecasts expect Spain to have the least GDP growth in 2010 and China the greatest, there is a wide range of forecasted earnings among companies based within each country. There are many companies headquartered in Spain whose growth prospects are better than companies domiciled in China. Likewise, while the P/E multiple of the Spanish market overall is significantly lower than that of the Chinese stock market, there are still many companies headquartered in China that are cheaper than those in Spain (Display 13). In the past, most investors who wished to invest globally determined geographic weighting first, then selected specific investments within those geographies. In an increasingly global marketplace, however, geographic weightings should be an effect—not a cause—of bottom-up stock selection. This may cause sector weightings to stray from geographical considerations. At the time of this writing, for example, Bernstein’s global research team found the most attractive materials sector opportunities in emerging markets companies. But we see the best technology opportunities in the US, while the best financials and telecom sector opportunities are in developed international countries. Opportunities for Bottom-Up Research While there is compelling potential in emerging markets today, the opportunities lie more in specific companies than in the markets as a whole—and these companies may be domiciled in emerging or developed countries. Due to the impact of ongoing market integration, investors should prepare for a world where Display 13 Attractive Stocks Can Be Found Within Every Country Fast-Growing Stocks Cheap Stocks 2010 Earnings Growth* Price/2010 Earnings* 28.3% 26.9% 65.2× 36.9× 9.8% 5.2% 10.9× 2.3× Spain China Top Decile Spain China Bottom Decile As of December 31, 2009 *Consensus earnings estimates; current estimates do not guarantee future results Source: MSCI, Thomson I/B/E/S, and AllianceBernstein exposure to stocks domiciled in emerging markets is simply the natural outgrowth of a global investment framework. Our research suggests that emerging markets should represent, on average, between 5% and 10% of global equity investments based on their fair share of the global opportunity set and the investor’s willingness to take on currency risk. Diversification across both stocks and markets will remain essential, as countryspecific events can still produce disappointing outcomes. Above all, investors should not overweight a country or region solely based on GDP growth expectations. Investment success will be determined by the ability to identify the companies that will benefit most from emerging markets growth and that will pass on those benefits to investors. Identifying these companies and investing in them successfully will be the result of bottomup stock research that is truly global in scale and perspective. n 7 Appendix 1: GDP* and Equity† Compound Annual Growth Rate Over Five-Year Periods Developed Countries 1989–1994 Country‡ GDP Equity 1995–1999 GDP Equity 2000–2004 GDP Equity 2005–2009 GDP Equity Australia 1.6% 8.4% 1.8% 8.8% 8.3% 13.2% 5.8% 12.3% Austria 7.9 0.4 0.8 (1.2) 6.0 21.8 5.0 (4.1) Belgium 8.0 7.2 1.3 19.1 6.8 5.1 4.5 (4.4) Denmark 6.6 3.2 2.1 19.4 6.7 8.2 4.3 9.7 Finland (3.5) 6.8 5.1 56.5 7.4 (13.5) 4.9 3.4 5.8 4.2 1.0 23.7 6.4 (0.1) 4.4 5.4 10.9 5.1 (0.2) 21.2 5.0 (3.1) 3.4 7.2 France Germany Greece — — — — — — 7.7 (2.4) 13.0 27.2 2.1 14.1 (0.2) (0.3) 3.9 9.3 Ireland — — 10.8 17.2 12.2 5.2 2.2 (18.0) Italy 3.3 (1.5) 2.6 19.3 7.3 5.0 3.0 (0.7) Japan 9.6 (3.4) (2.0) 2.1 0.9 (6.3) 1.9 (0.7) Malaysia (Former) (Retired) — — (1.2) (8.8) — — — — Netherlands 7.2 13.2 2.8 22.4 7.5 (2.5) 4.6 6.6 New Zealand 2.2 7.6 1.0 2.6 10.2 14.9 1.0 (1.1) Norway 3.8 3.5 4.4 6.5 9.6 13.7 6.4 10.6 Portugal — — — — 7.3 2.1 3.8 4.6 15.0 16.0 0.2 3.8 4.8 (3.7) 5.5 14.6 Spain 4.9 0.4 3.3 30.0 9.6 5.7 4.9 11.3 Sweden 0.6 5.4 3.2 34.1 6.5 (1.6) 1.7 6.6 Switzerland 6.6 14.8 (0.6) 20.1 6.0 3.4 5.8 7.2 United Kingdom 4.0 8.6 6.9 20.2 7.5 0.4 (0.6) Hong Kong Singapore R2 0.14 0.18 0.17 2.4 0.11 Total R2—All Periods 0.01 R2 is a statistical measure that captures how much one statistic predicts another. For example, if the R2 between GDP growth and local equity market growth is 0.14, that means that GDP growth explained about 14% of the change in local equity market growth. Other factors accounted for about 86% of the movement. Developed and Emerging countries categorized as such by MSCI at the beginning of each period, as of December 31, 2009 (Malaysia categorized as both emerging and developed in the 1995–1999 time period.) *GDP is expressed in current US dollars per person. Data are derived by first converting GDP in national currency to US dollars and then dividing it by total population. †All values annualized; nominal stock market returns ‡Each series is comprised of those countries that were categorized as Emerging or Developed by MSCI at the start of any one of the periods. Source: IMF, MSCI, and AllianceBernstein 8 Companies, Not Countries: The Real Opportunity in Emerging Markets Appendix 2: GDP* and Equity† Compound Annual Growth Rate Over Five-Year Periods Emerging Countries 1989–1994 1995–1999 Country‡ GDP Equity Argentina 23.9% 28.7% 0.8% GDP 2000–2004 Equity GDP 11.4% (12.6)% 1.0 Equity 2005–2009 GDP Equity (5.1)% 13.6% 14.4% 8.4 16.2 32.9 Brazil 2.3 26.9 (1.8) 8.2 Chile 12.3 46.8 4.3 (2.5) 4.2 9.5 8.2 18.6 China — — — — 11.5 (3.0) 19.1 23.8 Colombia — — (0.8) (10.2) 1.5 34.2 13.2 30.2 Czech Republic — — — — 12.8 34.9 11.1 17.6 Egypt — — — — — — 16.4 26.4 Greece 7.0 8.3 4.0 33.8 10.6 (5.3) — — Hungary — — — — 16.6 17.2 4.2 4.8 India — — 5.2 2.1 7.0 7.7 11.5 20.9 Indonesia 10.3 (2.1) (6.0) (13.7) 9.8 6.2 13.4 25.6 Israel — — — — 0.7 2.8 9.0 13.3 Jordan 2.1 10.6 2.8 (1.1) 4.4 22.4 12.0 (1.5) Korea — — 0.1 (1.5) 8.6 6.3 1.8 12.9 Malaysia 10.9 13.9 (1.2) (8.8) — — 8.8 12.9 Mexico 13.6 32.5 0.9 11.7 6.2 10.0 2.0 16.2 Morocco — — — — — — 8.4 19.2 Pakistan — — 0.0 (15.3) 4.4 23.8 9.2 3.1 Peru — — 1.2 1.0 4.6 19.0 11.0 34.5 Philippines 6.0 23.5 1.4 (14.5) 0.4 (10.6) 10.6 17.8 Poland — — 10.1 8.0 8.8 9.1 10.9 7.7 Portugal 10.8 (3.4) 4.7 18.8 — — — — Russia — — — — 25.3 18.6 16.7 12.6 South Africa — — — — 9.0 13.2 3.9 12.4 Sri Lanka — — 4.6 (14.3) 3.6 13.4 — — Taiwan — — — — 1.5 (6.4) 1.1 6.7 Thailand 13.3 17.5 (4.1) (23.3) 4.5 7.3 9.9 10.4 Turkey 1.9 (7.5) 6.2 37.2 7.1 (5.5) 7.5 13.9 Venezuela — — 8.6 4.9 1.0 12.8 — — R2 0.15 0.26 0.08 0.22 Total R2—All Periods 0.25 Developed and Emerging countries categorized as such by MSCI as of December 31, 2009 *GDP is expressed in current US dollars per person. Data are derived by first converting GDP in national currency to US dollars and then dividing it by total population. †All values annualized; nominal stock market returns ‡Each series is comprised of those countries that were categorized as Emerging or Developed by MSCI at the start of any one of the periods. Source: IMF, MSCI, and AllianceBernstein 9 Appendix 3: GDP Growth and EPS Growth Developed Countries EPS* Country Start Dates‡ Start End Australia 1989 $20.30 30.54 Austria 1989 18.21 Belgium 1989 41.59 Denmark 1989 Finland France GDP Per Capita ($000)† CAGR Start End 2.0% 16.1 42.0 CAGR 4.7% 43.37 4.2 17.5 45.1 4.6 18.70 (3.7) 15.7 43.0 4.9 32.42 153.35 7.7 22.1 55.9 4.5 1989 7.99 17.19 3.7 21.8 45.9 3.6 1989 32.16 85.69 4.8 17.9 42.1 4.2 Germany 1989 27.50 37.44 1.5 16.0 39.4 4.4 Greece 1992 17.76 43.71 5.4 10.6 30.3 6.4 Hong Kong 1989 123.38 300.81 4.3 10.5 29.6 5.0 Ireland 1993 8.86 8.72 (0.1) 14.1 51.1 8.4 Italy 1989 14.63 24.17 2.4 15.2 35.0 4.0 Japan 1989 76.11 (62.75) (5.1) 24.2 39.6 2.4 Netherlands 1989 46.55 32.57 (1.7) 16.4 47.0 5.2 New Zealand 1989 9.72 5.74 (2.5) 13.3 25.4 3.1 Norway 1989 21.81 84.14 6.6 23.7 76.7 5.7 Portugal 1992 5.56 8.86 2.8 10.4 20.7 4.1 Singapore 1989 43.69 190.25 7.3 8.9 34.3 6.6 Spain 1989 9.59 53.14 8.5 9.4 31.1 5.9 Sweden 1989 63.03 227.21 6.3 23.0 43.1 3.0 Switzerland 1989 33.17 88.41 4.8 29.2 66.1 4.0 United Kingdom 1989 39.57 83.35 3.6 15.0 35.7 4.2 Developed and Emerging countries categorized as such by MSCI as of December 31, 2009 *Trailing 12-month EPS as recorded on the final calendar day of each year. †GDP is expressed in current US dollars per person. Data are derived by first converting GDP in national currency to US dollars and then dividing it by total population. ‡Start and end dates were determined by the earliest year earnings data became available for each country by MSCI. Countries with less than 12 years of EPS data were omitted from this analysis to preserve statistical integrity. Source: IMF, MSCI, and AllianceBernstein 10 Companies, Not Countries: The Real Opportunity in Emerging Markets Appendix 4: GDP Growth and EPS Growth Emerging Countries EPS* Start GDP Per Capita ($000)† Country Start Dates‡ End CAGR Start End CAGR Argentina 1992 $12.88 $263.74 19.4 6.8 7.5 0.5% Brazil 1994 57.79 212.82 9.1 3.8 7.7 4.8 Chile 1992 36.53 109.67 6.7 3.3 8.9 6.0 China 1996 4.51 3.08 (2.9) 0.7 3.6 13.3 Colombia 1994 7.17 31.46 10.4 2.4 4.7 4.5 Czech Republic 1996 8.75 52.01 14.7 6.0 18.2 8.9 Greece 1992 17.76 43.71 5.4 10.6 30.3 6.4 Hungary 1996 7.63 52.14 15.9 4.4 12.4 8.3 India 1994 5.09 21.49 10.1 0.3 1.0 7.9 Indonesia 1992 19.89 38.66 4.0 0.8 2.2 6.0 Israel 1995 5.09 12.93 6.9 18.6 51.1 7.5 Jordan 1995 4.58 9.44 5.3 1.6 3.8 6.4 Korea 1995 10.90 18.40 3.8 12.0 16.4 2.3 Malaysia 1992 9.72 16.86 3.3 3.2 7.5 5.1 Mexico 1992 99.53 226.79 5.0 4.2 8.0 3.9 Pakistan 1994 6.95 8.11 1.0 0.5 1.0 4.5 Peru 1994 5.46 46.53 15.4 2.0 4.4 5.5 Philippines 1992 25.67 14.09 (3.5) 0.8 1.7 4.4 Poland 1995 46.52 46.67 0.0 3.6 11.1 8.4 Portugal 1992 5.56 8.86 2.8 10.4 20.7 4.1 Russia 1997 16.42 50.86 9.9 2.7 8.9 10.3 South Africa 1995 14.73 28.18 4.7 3.7 5.6 3.1 Sri Lanka 1994 13.04 2.15 (11.3) 0.7 2.0 7.3 Taiwan 1996 10.54 1.06 (16.2) 13.4 15.4 1.0 Thailand 1992 22.87 11.71 (3.9) 1.9 4.0 4.4 Turkey 1992 15.32 42.08 6.1 3.9 8.4 4.6 Venezuela 1995 9.51 28.91 9.7 3.5 8.3 7.3 Developed and Emerging countries categorized as such by MSCI as of December 31, 2009. *Trailing 12-month EPS as recorded on the final calendar day of each year †GDP is expressed in current US dollars per person. Data are derived by first converting GDP in national currency to US dollars and then dividing it by total population. ‡Start dates were determined by the earliest year earnings data became available for each country by MSCI. Countries with less than 12 years of EPS data were omitted from this analysis to preserve statistical integrity. All periods end in 2009, except for Venezuela which ends in 2007. Source: IMF, MSCI, and AllianceBernstein 11 © 2010 AllianceBernstein L.P. Note to All Readers: The information contained herein reflects, as of the date hereof, the views of AllianceBernstein L.P. (or its applicable affiliate providing this publication) (“AllianceBernstein”) and sources believed by AllianceBernstein to be reliable. No representation or warranty is made concerning the accuracy of any data compiled herein. In addition, there can be no guarantee that any projection, forecast, or opinion in these materials will be realized. Past performance is neither indicative of, nor a guarantee of, future results. The views expressed herein may change at any time subsequent to the date of issue hereof. This material is provided for informational purposes only, and under no circumstances may any information contained herein be construed as investment advice. AllianceBernstein does not provide tax, legal, or accounting advice. The information contained herein does not take into account your particular investment objectives, financial situation, or needs, and you should, in considering this material, discuss your individual circumstances with professionals in those areas before making any decisions. Any information contained herein may not be construed as any sales or marketing materials in respect of, or an offer or solicitation for the purchase or sale of, any financial instrument, product, or service sponsored or provided by AllianceBernstein L.P. or any affiliate or agent thereof. References to specific securities are presented solely in the context of industry analysis and are not to be considered recommendations by AllianceBernstein. AllianceBernstein and its affiliates may have positions in, and may effect transactions in, the markets, industry sectors, and companies described herein. Bernstein Global Wealth Management is a unit of AllianceBernstein L.P. Note to UK Readers: AllianceBernstein Global Wealth Management is a unit of AllianceBernstein Limited. AllianceBernstein Limited (FRN147956) is authorised and regulated in the United Kingdom by the Financial Services Authority. Issued by AllianceBernstein Limited, Devonshire House, 1 Mayfair Place, London W1J 8AJ. Bernstein Global Wealth Management and AllianceBernstein Global Wealth Management do not offer tax, legal, or accounting advice. In considering this material, you should discuss your individual circumstances with professionals in those areas before making any decisions. BER–6233–0310 www.bernstein.com | 212.486.5800