* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download 5.3 Ideals and Factor Rings

Factorization of polynomials over finite fields wikipedia , lookup

Fundamental theorem of algebra wikipedia , lookup

Eisenstein's criterion wikipedia , lookup

Congruence lattice problem wikipedia , lookup

Birkhoff's representation theorem wikipedia , lookup

System of linear equations wikipedia , lookup

Gröbner basis wikipedia , lookup

Ring (mathematics) wikipedia , lookup

Dedekind domain wikipedia , lookup

Algebraic number field wikipedia , lookup

5.3

5.3

J.A.Beachy

1

Ideals and Factor Rings

from A Study Guide for Beginner’s by J.A.Beachy,

a supplement to Abstract Algebra by Beachy / Blair

27. Give an example to show that the set of all zero divisors of a commutative ring need

not be an ideal of the ring.

Solution: The elements (1, 0) and (0, 1) of Z×Z are zero divisors, but if the set of zero

divisors were closed under addition it would include (1, 1), an obvious contradiction.

28. Show that in R[x] the set of polynomials whose graph passes through the origin and

is tangent to the x-axis at the origin is an ideal of R[x].

Solution: We can characterize the given set as I = {f (x)R[x] | f (0) = 0 and f ′ (x) =

0}. Using this characterization of I, it is easy to check that if f (x), g(x) ∈ I, then

f (x) ± g(x) ∈ I. If g(x) ∈ R[x] and f (x) ∈ I, then g(0)f (0) = g(0) · 0 = 0, and

Dx (g(x)f (x)) = g ′ (x)f (x) + g(x)f ′ (x), and so evaluating at x = 0 gives g′ (0)f (0) +

g(0)f ′ (0) = g′ (0) · 0 + g(0) · 0 = 0. This shows that I is an ideal of R[x].

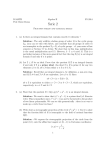

29. To illustrate Proposition 5.3.7 (b), give the lattice diagram of ideals of Z100 = Z/ h100i,

and the lattice diagram of ideals of Z that contain h100i.

Solution: Since multiplication in Z100 corresponds to repeated addition, each subgroup of Z100 is an ideal, and the lattice diagram is the same as that of the subgroups

of Z100 , given in the following diagram.

Z100

@

5Z100

2Z100

@

4Z100

@

@

10Z100

@

25Z100

50Z100

20Z100

@

h0i

The ideals of Z that contain h100i correspond to the positive divisors of 100.

Z

@

h2i

h5i

@

@

h4i

h10i

@

@

h20i

@

h50i

h100i

30. Let R be the ring Z2 [x]/ x3 + 1 .

h25i

5.3

J.A.Beachy

2

Comment: Table 5.1 gives the multiplication table, though it is not necessary to

compute it in order to solve the problem.

Table 5.1: Multiplication in Z2 [x]/ x3 + 1

x2 +x x+1 x2 +1 x2 +x+1

1

x

x2

2

2

2

2

x +x x+1 x +1

0

x +x

x +1

x+1

2

2

2

x+1 x +1 x +x

0

x+1

x +x

x2 +1

x+1

2

2

2

2

x +1

x +1 x +x x+1

0

x +1

x+1

x2 +x

0

0

0

x2 +x+1 x2 +x+1 x2 +x+1 x2 +x+1

x2 +x+1

2

2

1

x +x x+1 x +1 x2 +x+1

1

x

x2

2

2

2

2

x +1 x +x x+1 x +x+1

x

x

1

x

2

2

2

2

2

x

x+1 x +1 x +x x +x+1

x

1

x

×

x2 +x

(a) Find all ideals of R.

Solution: By

Proposition

5.3.7 (b), the ideals of R correspond to the ideals of Z2 [x]

3

that contain x + 1 . We have the factorization x3 + 1 = x3 − 1 = (x − 1)(x2 + x + 1),

so the only proper, nonzero ideals are the principal ideals given below.

A = h[x + 1]i = {[0], [x2 + x], [x + 1], [x2 + 1]}

B = [x2 + x + 1] = {[0], [x2 + x + 1]}

Comment: We note that R = A ⊕ B, accounting for its 8 elements.

(b) Find the units of R.

Solution: We have [x]3 = [1], so [x] and [x2 ] are units. To show that the only units are

1, [x], and [x2 ], note that [x + 1][x2 + x + 1] = [x3 + 1] = [0], so [x + 1] and [x2 + x + 1]

cannot be units. This also excludes [x2 + x] = [x][x + 1] and [x2 + 1] = [x2 ][1 + x].

(c) Find the idempotent elements of R.

Solution: Using the general fact that (a + b)2 = a2 + 2ab + b2 = a2 + b2 (since Z2 [x]

has characteristic 2) and the identities [x3 ] = [1] and [x4 ] = [x], it is easy to see that

the idempotent elements of R are [0], [1], [x2 + x + 1], and [x2 + x].

31. Let S be the ring Z2 [x]/ x3 + x .

Comment: It isn’t necessary to construct Table 5.2 in order to answer (a) and (b).

(a) Find all ideals of S.

Solution: Over Z2 we have the factorization x3 + x = x(x2 + 1) = x(x + 1)2 , so by

Proposition 5.3.7 (b) the proper nonzero ideals of S are the principal ideals generated

by [x], [x + 1], [x2 + 1] = [x + 1]2 , and [x2 + x] = [x][x + 1].

A = h[x]i = {[0], [x2 ], [x], [x2 + x]} ⊇ C = [x2 + x] = {[0], [x2 + x]}

B = [x2 + 1] = {[0], [x2 + 1]}

B + C = h[x + 1]i = {[0], [x + 1], [x2 + 1], [x2 + x]}

Comment: We note that S = A ⊕ B.

5.3

J.A.Beachy

3

Table 5.2: Multiplication in Z2 [x]/ x3 + x

x2

×

x2

x2

x

x

2

2

x +x

x +x

0

x2 +1

x+1

x2 +x

x2

1

2

x +x+1 x2

x

x

x2

x2 +x

0

x2 +x

x

x

x2 +x

x2 +x

x2 +x

0

0

0

x2 +x

x2 +x

x2 +1

0

0

0

x2 +1

x2 +1

x2 +1

x2 +1

x+1

x2 +x

x2 +x

0

x2 +1

x2 +1

x+1

x+1

1

x2 +x+1

x2

x2

x

x

2

2

x +x

x +x

x2 +1

x2 +1

x+1

x+1

2

1

x +x+1

x2 +x+1

1

(b) Find the units of S.

Solution: Since no unit can belong to a proper ideal, it follows from part (a) that we

only need to check [x2 + x + 1]. This is a unit since [x2 + x + 1]2 = [1].

(c) Find the idempotent elements of S.

Solution: Since [x3 ] = [x], we have [x2 ]2 = [x2 ], and then [x2 + 1]2 = [x2 + 1]. These,

together with [0] and [1], are the only idempotents.

32. Show that the rings R and S in Problems 30 and 31 are isomorphic as abelian groups,

but not as rings.

Solution: Both R and S are isomorphic to Z2 × Z2 × Z2 , as abelian groups. They

cannot be isomorphic as rings since S has a nonzero nilpotent element, [x2 + x], but R

does not. We can also prove this by noting that the given multiplication tables show

that R has 3 units, while S has only 2.

33. Let I, J be ideals of the commutative ring R, and for r ∈ R, define the function

φ : R → R/I ⊕ R/J by φ(r) = (r + I, r + J).

(a) Show that φ is a ring homomorphism, with ker(φ) = I ∩ J.

Solution: The fact that φ is a ring homomorphism follows immediately from the

definitions of the operations in a direct sum and in a factor ring. Since the zero

element of R/I ⊕ R/J is (0 + I, 0 + J), we have r ∈ ker(φ) if and only if r ∈ I and

r ∈ J, so ker(φ) = I ∩ J.

(b) Show that if I + J = R, then φ is onto, and thus R/(I ∩ J) ∼

= R/I ⊕ R/J.

Solution: If I + J = R, then we can write 1 = x + y, for some x ∈ I and y ∈ J.

Given any element (a + I, b + J) ∈ R/I ⊕ R/J, consider r = bx + ay, noting that

a = ax + ay and b = bx + by. We have a − r = a − bx − ay = ax − bx ∈ I, and

b − r = b − bx − ay = by − ay ∈ J. Thus φ(r) = (a + I, b + J), and φ is onto. The

isomorphism follows from the fundamental homomorphism theorem.

Comment: This result is sometimes called the Chinese remainder theorem for commutative rings. It is interesting to compare this proof with the one given for Theorem 1.3.6.

5.3

J.A.Beachy

4

34. Let I, J be ideals of the commutative ring R. Show that if I +J = R, then I 2 +J 2 = R.

Solution: If I + J = R, then there exist a ∈ I and b ∈ J with a + b = 1. Cubing both

sides gives us a3 + 3a2 b + 3ab2 + b3 = 1. Then we only need to note that a3 + 3a2 b ∈ I 2

and 3ab2 + b3 ∈ J 2 .

35. Show that x2 + 1 is a maximal ideal of R[x].

2

Solution:

R,

2 Since

x + 1 is irreducible

over

it follows from results in Chapter 4 that

2

R[x]/ x + 1 is a field. Therefore x + 1 is a maximal ideal.

36. Is x2 + 1 a maximal ideal of Z2 [x]?

Solution:

Since x2 + 1 is not irreducible over Z2 , the ideal it generates is not a

maximal ideal. In fact, x + 1 generates a larger ideal since it is a factor of x2 + 1.

37. Let R and S be commutative rings, and let φ : R → S be a ring homomorphism.

(a) Show that if I is an ideal of S, then φ−1 (I) = {a ∈ R | φ(a) ∈ I} is an ideal of R.

Solution: If a, b ∈ φ−1 (I), then φ(a) ∈ I and φ(b) ∈ I, so φ(a ± b) = φ(a) ± φ(b) ∈ I,

and therefore a ± b ∈ φ−1 (I). If r ∈ R, then φ(ra) = φ(r)φ(a) ∈ I, and therefore

ra ∈ φ−1 (I). By Definition 5.3.1, this shows that φ−1 (I) is an ideal of R.

(b) Show that if P is a prime ideal of S, then φ−1 (P ) is a prime ideal of R.

Solution: Suppose that P is a prime ideal of R and ab ∈ φ−1 (P ) for a, b ∈ R. Then

φ(a)φ(b) = φ(ab) ∈ P , so φ(a) ∈ P or φ(b) ∈ P since P is prime. Thus a ∈ φ−1 (P ) or

b ∈ φ−1 (P ), showing that φ−1 (P ) is prime in R.

38. Prove that in a Boolean ring every prime ideal is maximal.

Solution: We will prove a stronger result: if R is a Boolean ring and P is a prime

ideal of R, then R/P ∼

= Z2 . Since Z2 is a field, Proposition 5.3.9 (a) implies that P

is a maximal ideal.

If a ∈ R, then a2 = a, and so a(a − 1) = 0. Since P is an ideal, it contains 0, and

then a(a − 1) ∈ P implies a ∈ P or a − 1 ∈ P , since P is prime. Thus each element

of R is in either P or 1 + P , so there are only two cosets of P in R/P , and therefore

R/P must be the ring Z2 .

39. In R = Z[i], let I = {m + ni | m ≡ n (mod 2)}.

(a) Show that I is an ideal of R.

Solution: Let a + bi and c + di belong to I. Then a ≡ b (mod 2) and c ≡ d (mod 2),

so a + c ≡ b + d (mod 2) and a − c ≡ b − d (mod 2), and therefore (a + bi) ± (c + di) ∈ I.

For m + ni ∈ R, we have (m + ni)(a + bi) = (ma − nb) + (na + mb)i. Then ma − nb ≡

na + mb (mod 2) since n ≡ m (mod 2) and −nb ≡ nb (mod 2). This completes the

proof that I is an ideal of R.

(b) Find a familiar commutative ring isomorphic to R/I.

Solution: Note that m + ni ∈ I if and only if m − n ≡ 0 (mod 2). Furthermore,

m + ni ∈ 1 + I if and only if 1 − (m + ni) ∈ I, and this occurs if and only if

5.3

J.A.Beachy

5

1 − m ≡ −n (mod 2) if and only if m − n ≡ 1 (mod 2). Since any element of m + ni

R satisfies either m − n ≡ 0 (mod 2) or m − n ≡ 1 (mod 2), the only cosets in R/I

are 0 + I and 1 + I. Therefore R/I ∼

= Z2 .

ANSWERS AND HINTS

45. Let P and Q be maximal ideals of the commutative ring R. Show that

R/(P ∩ Q) ∼

= R/P ⊕ R/Q.

Hint: If you can show that P + Q = R, then you can use Problem 33 (b).

√

√

by 2 is a maximal ideal.

48. Show that in Z[ 2] the principal ideal generated

√

Hint: Define a ring homomorphism from Z[ 2] onto Z2 .