* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Historical Experience with Low Inflation

Edmund Phelps wikipedia , lookup

Real bills doctrine wikipedia , lookup

Economic bubble wikipedia , lookup

Fear of floating wikipedia , lookup

Full employment wikipedia , lookup

Business cycle wikipedia , lookup

Post–World War II economic expansion wikipedia , lookup

Long Depression wikipedia , lookup

Nominal rigidity wikipedia , lookup

Monetary policy wikipedia , lookup

Interest rate wikipedia , lookup

Phillips curve wikipedia , lookup

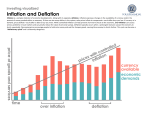

America's Historical Experience with Low Inflation I. Introduction The inflation that struck the United States in the 1970s still shapes a large chunk of our thought about macroeconomic policy. The inflation of the 1970s was high enough to potentially induce significant distortions in investment as a result of the interaction of inflation with our tax system (unable as it is to adequately adjust for the difference between nominal and real income). It transferred substantial wealth from creditors to debtors. It rendered accounting statements constructed according to standard accounting principles thoroughly untrustworthy. And the inflation of the 1970s has cast its shadow upon forecasts of the likely future of the American economy--practically everyone's expectation of what inflation might be is influenced by the experience of the 1970s. Yet our inflation rate is now quite low--we seem to think that there is a greater chance that inflation will average one percent than that it will average five percent over the next decade. The last experience we had with 2 First, a look back at history reveals that the sustained inflation of the 1970s was an anomaly in American history. There had been previous peaks of inflation higher than or as high as was reached in the 1970s--during total war and during the bounce-back from the deflation of the early 1930s. But these three episodes aside, for the entire century between the end of the Civil War and the late 1960s GDP-deflator inflation in the United States had always been less than five percent per year, and had usually been less than three percent per year. In peacetime the United States was a hard-money country. This is the first lesson from history: William Jennings Bryan, after all, lost the election of 1896 when he campaigned on the platform of free coinage of silver at a rate of 16-to-1--and the free-silver inflationists framed their issue not as causing inflation but reversing the deflation caused by the Crime of 1873. Neither the Republican nor the Democratic Party sought at the end of 1970s to run on a platform of tolerating inflation in order to achieve the benefits of a high-pressure economy. Both political parties today fall over themselves to praise the current leadership of the Federal Reserve. Thus anyone forecasting the future from today has to be willing to give long odds that the low levels of inflation America has experienced since the early 1980s will continue. 3 A second lesson from history is that perhaps we have less to fear from deflation in times of low inflation than we fear--but also that we have more to fear from deflation in general than we fear. We today think that deflation was so dangerous in previous eras (and perhaps in Japan today) because of the principal-agent problem that confronts investors who commit their funds to enterprises. The economy has and has long had a lot of nominal debt contracts. Deflation destroys the ability of entrepreneurs to service their nominal debt obligations. The existence of nominal debt contracts means that to the financial system deflation appears to be a signal that entrepreneurs have failed, and that their enterprises need to be liquidated. This makes deflation destructive: valuable organizations are liquidated and webs of intermediation are torn for no fundamental purpose. Monetary policy is the stabilization policy tool of choice. But the ability of the Federal Reserve to offset shocks to the price level at any horizon of less than three or four years is limited. If you assume a symmetrical distribution of price shocks, and if you take your estimates of the effectiveness of 4 monetary policy from recent work by Christiano, Eichenbaum, and Evans, you can reach the conclusion that there is a one-in-twenty chance that the price level two-and-a-half years hence will be eight percentage points or more below today's best forecast. But the joker in the debt is the assumption of symmetry. The high variance of the price level about its forecast is driven in large part by upward spikes in prices during the inflation of the 1970s. However, credit-channel analyses suggest that large-scale asset price declines set in motion the same potential contractionary forces as do goods and services price declines. In the past such large-scale asset price declines have been more likely--and looking ahead to the future they appear more likely--than large-scale declines in broad goods and services price indexes. And the most damaging effects of deflation--at least of asset-price deflation-may well be set up by a previous period of inflation. Inflation leads to an increasing degree of leverage in the financial system: more debt contracts, thus a greater chance for declines in asset prices to tear the web of financial intermediation. Low trend inflation does raise the chance that a contractionary shock might push goods-and-services price indexes down. But what we fear about 5 deflation is generated more easily by asset price "deflations" than by goodsand-services price index "deflations." A third lesson deals with the Fisher effect. All economists believe deep in their bones in the theory of the Fisher effect: theory tells us that if one changes the average trend rate of inflation, and if one then waits long enough, nominal interest rates will adjust point-for-point (or possibly more than point-for-point given the interaction of inflation and the tax system) to the change in the rate of inflation, and real interest rates will return to equilibrium. The end of moderate inflation in the United States in the early 1980s also saw a substantial increase in real interest rates--an increase that has not yet been reversed: real interest rates are still higher today than they were in the 1950s or 1960s. Back in 1984 when economists first noted this rise in interest rates, Olivier Blanchard and Lawrence Summers attributed it to an increase in the return on capital springing from deregulation and reductions in marginal tax rates. But the increase in economic growth over the following decade that one would have expected to result from an investment boom driven by an increase in the return on capital did not happen. 6 Thus today it seems much more likely that relatively high real interest rates in financial markets are a result of some failure of the Fisher effect: investors appear to believe that there is a significant chance of a renewal of inflation like that of the 1970s. Historical experience tells us that such failures of the Fisher effect for prolonged periods of time--generations--are not at all uncommon. In an assiduous close reading of Irving Fisher's The Rate of Interest, Robert Barsky found that Irving Fisher in the end concluded that participants in financial markets back at the turn of the last century were not competent to apply his theory: "The inrushing streams of gold [after 1896] caught merchants napping." Fisher wrote. "They should have stemmed the tide by putting up [nominal] interest… two or three percent[age] points higher…" Long-run historical experience gives us no reason to be confident that the Fisher effect will hold, at least not in any time shorter than a generation. Yet the lesson of history for the effect of an age of low inflation on the real interest rate is double-edged. For the failure of the Fisher effect does not seem to have any of the feared effect on the level of investment: the failure 7 of expectations to adjust fully to a changed trend inflation environment appears to be present on both sides of the market, and to have few consequences other than to redistribute wealth from creditors to debtors. The fourth and least lesson concerns inflation and productivity growth. The idea behind low inflation is to remove some sand from the wheels of the price mechanism. In an effectively-zero-inflation climate, people can have more trust that the real prices they see are likely to persist near their current levels rather than being always in motion as one of the (s, S) mechanisms elegantly modeled by Andrew Caplin and others recurrently ratchets real prices of individual commodities to levels that are temporarily high and then temporarily low. With one fewer thing to worry about, the organizational time and effort that had gone into forecasting inflation and interpreting news in an inflationary environment can be devoted to analyzing other things instead--and at least some of those other things should raise economic productivity. In the absence of convincing evidence to the contrary, economists' priors will remain centered on the belief that low inflation is a source of stronger economic growth. 8 But does low inflation in fact produce faster productivity growth? Glenn Rudebusch and David Wilcox, among others, have found striking correlations between productivity growth and inflation, but could not convincingly show causation. After all, if total nominal demand is predetermined then a strong correlation between high productivity and low inflation is guaranteed by the identity that quantity times price equals expenditure. In the last analysis, confidence that low inflation is a goal worth pursuing has to rest on (i) the theoretical prior that removing managers' and workers' need to focus attention on the problem of forecasting inflation must be worthwhile, and (ii) the expressed preference--documented in studies by Robert Shiller and others--that voters' and citizens' appear to have for low rates of inflation.