* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download ADVISORS TO THE UMAYYAD CALIPH

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

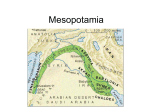

Umayyad Caliphate Simulation Introduction: You are a team of advisors to the Umayyad Caliph in the year 742CE. The Umayyad Empire is in turmoil with 50,000 formerly loyal warriors who have settled in the Persian part of the empire rallying around the rebel al-Abbas (an uncle of Muhammad, praise his name). As advisors, you must help the Caliph make important policy changes to avoid a disastrous civil war and the possible fall of the Caliphate! Overview of the Process & Timeline: Step 1 – determine what problems the Caliphate is facing. (15 minutes) Each member of your group will research one aspect of the empire and identify problems: political, economic, religious, and social. To do so, you will consult the latest intelligence report of the condition of the empire. Step 2 – Consult the book of ancient wisdom. (20 minutes) Your team of advisors will consult the famous Book of Classical Wisdom to determine why empires appear to fall. You will use the book’s model for the fall of empires known as the “Conrad-Demarest” model, identify how the model applied to the fall of Rome and Han China, and figure out whether the problems identified in step 1 are likely to result in an imperial collapse. Step 3 – Advise the Caliph!(15 minutes) Your team will create a list of policy recommendations for the caliph addressing all of the existing problems in the Ummayad Caliphate. In order to convince the Caliph that the problems are significant, you will use the historical examples from the classical period you found in step 2. Good luck and Allah be with you! Remember – the consequences for failure are the fall of the Caliphate and your death at the hands of the rebel Abbasids! BRIEFING - ADVISORS TO THE UMAYYAD CALIPH STEP 1 – identify the problems the Caliphate is facing. Divide your research responsibilities up into the following categories, with one group member taking a category: Political problems, Economic problems, Religious problems, and Social Problems. Your problem area for research_______________________________________ 1. According to the latest intelligence reports, what issues does the caliphate face in your problem area? Issue A: Issue B: Issue C: STEP 2 – Consult the book of wisdom. The Book of Classical Wisdom says that, according to Conrad Demarest, Empires fall due to the following factors: 1. Failure of leadership: a focus on wealth and luxury, personal glory, etc. instead of the needs to the state by those in power. 2. A belief in continuous military expansion and conquest leading to “imperial overstretch” of the bureaucracy, military, resources, communications. 3. A lack of new conquests that erodes the economic base and reduces faith in the beliefs (in this case religion) that supported the empire. 4. Rebellions from within or challenges from without. Conrad Demarest from the Book of Classical Wisdom1 As a group look at the histories and find examples of how the Han and Roman Empires fell because of these factors. You will need examples to give the Caliph to convince him to change Umayyad policies and practices! Factor leading to collapse In Han China? Failure of leadership: a focus on wealth and luxury, personal glory, etc. instead of the needs to the state by those in power. 1 Just kidding. There is no “Book of Classical Wisdom”. In Roman Empire? A belief in continuous military expansion and conquest leading to “imperial overstretch” of the bureaucracy, military, resources, communication. A lack of new conquests that erodes the economic base and reduces faith in the beliefs (in this case religion) that supported the empire. Rebellions from within or challenges from without Step 3 – What an ideal empire looks like. According to Conrad Demarest in the Book of Classical Wisdom, successful empires have the following attributes. Your solutions should be inspired by this vision of the “ideal” empire: Good roads & transportation canals, ports, etc High volume of trade Cosmopolitan cities – art & education flourish Effective bureaucracy to ensure communication, collect taxes, oversee coinage, and ensure the emperor’s laws are enforced A common official language A system of justice, law for the entire empire Citizenship or rights are extended in some degree to the conquered Economic reward to the elite “trickle down” to the other classes Step 4 – Problems in the Umayyad Caliphate. Identify problems and provide solutions for the Caliph. Based on your research into the historical record, make your recommendations to the Caliph. PROBLEMS YOU SEE IN THE UMAYYAD CALIPHATE & HISTORICAL PARALLELS: Sign of imperial decline/problem Historical example (as in Rome or Han China) Step 5 – YOUR PROPOSALS TO THE CALIPH 1. 2. 3. INTELLIGENCE BRIEFING The Umayyad Imperium By the early 700s, the Umayyads ruled an empire that extended from Spain in the west to the steppes of central Asia in the east. Not since the Romans had there been an empire to match it; never had an empire of its size been built so rapidly. Although Mecca remained the holy city of Islam, under the Umayyads the political center of community shifted to Damascus in Syria, where the Umayyads chose to live after the murder of Uthman The empire was very much an Arab conquest state. Except in the Arabian peninsula and in parts of the Fertile Crescent, a small Arab and Muslim aristocracy ruled over peoples who were neither Arab nor Muslim. Only Muslim Arabs were first- class citizens of this great empire. They made up the core of the army and imperial administration, and only they received a share of the booty derived from the ongoing conquests. They could be taxed only for charity. The Umayyads sought to keep the Muslim warrior elite concentrated in garrison towns and separated from the local population. It was hoped that isolation would keep them from assimilating to the subjugated cultures, because intermarriage meant conversion and the loss of taxable subjects. Converts and “People of the Book” Umayyad attempts to block extensive interaction between the Muslim warrior elite and their non-Muslim subjects had little chance of succeeding. The citified bedouin tribes were soon interacting intensively with the local populations of the conquered areas and intermarrying with them. Equally critical, increasing numbers of these peoples were voluntarily converting to Islam, despite the fact that conversion did little to advance them socially or politically in the Umayyad period. In this era Muslim converts, mawali, still had to pay property taxes and in some cases the head tax, levied on nonbelievers. They received no share of the booty and found it difficult, if not impossible, to get important positions in the army or bureaucracy. They were not even considered full members of the umma but were accepted only as clients of the powerful Arab clans. As a result, the number of conversions in the Umayyad era was low. Umayyad Decline and Fall The ever-increasing size of the royal harem was just one manifestation of the Umayyad caliphs’ growing addiction to luxury and soft living. Their legitimacy had been disputed by various Muslim factions since their seizure of the caliphate. But the Umayyads further alienated the Muslim faithful as they became more aloof in the early 8th century and retreated from the dirty business of war into their pleasure gardens and marble palaces. Their abandonment of the frugal, simple lifestyle followed by Muhammad and the earliest caliphs—including Abu Bakr, who made a trip to the market the day after he was selected to succeed the prophet—enraged the dissenting sects and sparked revolts throughout the empire. The uprising that proved fatal to the short-lived dynasty began among the frontier warriors who had fought and settled in distant Iran. By the mid-8th century, more than 50,000 warriors had settled near the oasis town of Merv in the eastern Iranian borderlands of the empire. Many of them had married local women, and over time they had come to identify with the region and to resent the dictates of governors sent from distant Damascus. The warrior settlers were also angered by the fact that they were rarely given the share of the booty, now officially tallied in the account books of the royal treasury,that they had earned by fighting the wars of expansion and defending the frontiers. They were contemptuous of the Umayyads and the Damascus elite, whom they saw as corrupt and decadent. In the early 740s, an attempt by Umayyad palace officials to introduce new troops into the Merv area touched off a revolt that soon spread over much of the eastern portions of the empire. On the Decline of the Roman Empire: SELECTION A Historians use the expression “third-century crisis” to refer to the period from 235 to 284 CE., in which political, military, and economic problems beset and nearly destroyed the Roman Empire. The most visible symptom of the crisis was the frequent change of rulers. It has been estimated that twenty or more men claimed the office of emperor during this period. Most reigned for only a few months or years before being overthrown by a rival or killed by their own troops. Germanic tribesmen on the Rhine/Danube frontier took advantage of the frequent civil wars and periods of anarchy to raid deep into the empire. For the first time in centuries, Roman cities began to erect walls for protection. Several regions, feeling that the central government in Rome was not adequately protecting them, turned power over to a man on the spot who promised to put their interests first. These political and military emergencies had a devastating impact on the empire’s economy. The cost of paying large rewards to the troops to win their support and of subsidizing the defense of the increasingly permeable frontiers drained the imperial treasury. In turn, the unending demands of the central government for more tax revenues from the provinces, as well as the interruption of commerce by fighting, eroded the towns’ prosperity. Shortsighted emperors, desperate for cash, secretly cut back the amount of precious metal in Roman coins and pocketed the excess. But the public quickly caught on, and the devalued coinage became less and less acceptable as a medium for exchange. Indeed, the empire reverted to a barter economy, a far less efficient system that further curtailed large-scale and long-distance commerce. The municipal aristocracy, once the most vital and public-spirited class in the empire, was slowly crushed out of existence. As town councilors, its members were personally liable to make up any shortfall in the tax revenues owed to the state. But the decline in trade eroded their wealth, which often was based on manufacture and commerce. Many began to evade their civic duties and even go into hiding. There was an overall shift of population out of the cities and into the countryside. Many people sought employment and protection—from raiders and from government officials—on the estates of wealthy and powerful country landowners. In the shrinking of cities and the movement of the population to the country estates, we can see the roots of the social and economic structures of the European Middle Ages—a roughly seven-hundred-year period in which wealthy rural lords dominated a peasant population tied to the land. …government regulation of prices and vocations … had unforeseen consequences. One was the creation of a “black market” among buyers and sellers who chose to ignore the government’s price controls and establish their own prices for goods and services. Another was a growing tendency among the inhabitants of the empire to consider the government an oppressive entity that no longer deserved their loyalty. SELECTION B On the decline of the Roman Empire: …the quality of political and economic life in the Roman Empire began to shift after about 180 c.e. Political confusion produced a series of weak emperors and many disputes over succession to the throne. Intervention by the army in the selection of emperors complicated political life and contributed to the deterioration of rule from the top More important in initiating the process of decline was a series of plagues that swept over the empire. As in China, the plagues’ source was growing international trade, which brought diseases endemic in southern Asia to new areas like the Mediterranean, where no resistance had been established even to contagions such as the measles. The resulting diseases decimated the population. The population of Rome decreased from a million people to 250,000. Economic life worsened in consequence. Recruitment of troops became more difficult, so the empire was increasingly reduced to hiring Germanic soldiers to guard its frontiers. The need to pay troops added to the demands on the state’s budget, just as declining production cut into tax revenues. Rome’s upper classes became steadily more pleasure-seeking, turning away from the political devotion and economic vigor that had characterized the republic and early empire. Cultural life decayed. Aside from some truly creative Christian writers—the fathers of Western theology— there was very little sparkle to the art or literature of the later empire. Many Roman scholars contented themselves with writing textbooks that rather mechanically summarized earlier achievements in science, mathematics, and literary style. Writing textbooks is not, of course, proof of absolute intellectual incompetence—at least, not in all cases— but the point was that new knowledge or artistic styles were not being generated, and even the levels of previous accomplishment began to slip. The later Romans wrote textbooks about rhetoric instead of displaying rhetorical talent in actual political life. And they wrote simple compendiums, for example, about animals or geometry, that barely captured the essentials of what earlier intellectuals had known, and often added superstitious beliefs that previous generations would have scorned. This cultural decline, finally, was not clearly due to disease or economic collapse, for it began in some ways before these larger problems surfaced. Something was happening to the Roman elite, perhaps because of the deadening effect of authoritarian political rule, perhaps because of a new interest in luxuries and sensual indulgence. Revealingly, the upper classes no longer produced many offspring, for bearing and raising children seemed incompatible with a life of pleasureseeking. Rome’s fall, in other words, can be blamed on large, impersonal forces that would have been hard for any society to control or a moral and political decay that reflected growing corruption among society’s leaders. Probably elements of both were involved. Thus, the plagues would have weakened even a vigorous society, but they would not necessarily have produced an irreversible downward spiral had not the morale of the ruling classes already been sapped by an unproductive lifestyle and superficial values. On the Decline of the Han Empire: SELECTION A For the Han government, as for the Romans, maintaining the security of the frontiers particularly the North and North West frontiers—was a primary concern. Yet, in the end, the pressure of non-Chinese peoples raiding from across the frontier or moving into the prosperous lands of the empire led to the decline of Han authority In general, the Han Empire was able to consolidate its hold over lands occupied by sedentary farming peoples, but nearby were nomadic tribes whose livelihood depended on their horses and herds. The very different ways of life of farmers and herders gave rise to suspicions and insulting stereotypes on both sides. The settled Chinese tended to think of nomads as “barbarians—rough, uncivilized peoples—much as the inhabitants of the Roman Empire looked down on the Germanic tribes living beyond their frontier. …The nomads sought the food commodities and crafted goods produced by the farmers and townsfolk, and the settled peoples depended on the nomads for horses and other herd animals and products. Sometimes, however, contact took the form of raids on the settled lands by nomad bands, which seized what they needed or wanted. Tough and warlike because of the demands of their way of life, mounted nomads could strike swiftly and just as swiftly disappear. In the end, the cost of continuous military vigilance along the frontier imposed a crushing burden on Han finances and worsened the economic troubles of later Han times. And, despite the earnest efforts of Qin and Early Han emperors to reduce the power and wealth of the aristocracy and to turn land over to a free peasantry, by the end of the first century B.C.E. nobles and successful merchants again were beginning to acquire control of huge tracts of land, and many peasants were seeking their protection against the exactions of the imperial government. This trend became widespread in the next two centuries. Strongmen largely independent of imperial control emerged, and the central government was deprived of tax revenues and manpower. The system of military conscription broke down, forcing the government to hire more and more foreign soldiers and officers. These men were willing to serve for pay, but their loyalty to the Han state was weak. Several factors combined to weaken and eventually bring down the Han dynasty in 220 CE.: factional intrigues within the ruling clan, official corruption and inefficiency, uprisings of desperate and hungry peasants, the spread of banditry unsuccessful reform movements, attacks by nomadic groups on the northwest frontier, and the ambitions of rural warlords. After 220 C.E. China entered a period of political fragmentation and economic and cultural regression … On the Decline of the Han Empire: SELECTION B By about 100 C.E., the Han dynasty in China entered a serious decline. Confucian intellectual activity gradually became less creative. Politically, the central government’s control diminished, bureaucrats became more corrupt, and local landlords took up much of the slack, ruling their neighborhoods according to their own wishes. The free peasants, long heavily taxed, were burdened with new taxes and demands of service by these same landlords. Many lost their farms and became day laborers on the large estates. Some had to sell their children into service. Social unrest increased, producing a great revolutionary effort led by Daoists in 184 G.E. Daoism now gained new appeal, shifting toward a popular religion and adding healing practices and magic to earlier philosophical beliefs. The Daoist leaders, called the Yellow Turbans, promised a golden age that was to be brought about by divine magic. The Yellow Turbans attacked the weakness of the emperor but also the selfindulgence of the current bureaucracy. As many as 30,000 students demonstrated against the decline of government morality. However, their protests failed, and Chinese population growth and prosperity spiraled further downward. The imperial court was mired in intrigue and civil war. This dramatic decline … explained China’s inability to push back invasions from borderland nomads, who finally overthrew the Han dynasty outright…growing political ineffectiveness formed part of the decline. Another important factor was the spread of devastating new epidemics, which may have killed up to half of the population. These combined blows not only toppled the Han but led to almost three centuries of chaos... Conrad-Demarest Model of Empires 1. Necessary preconditions for the rise of empires—the region must have: a) State-level government b) High agricultural potential of the environment c) An environmental mosaic d) Several small states with no clear dominant state (power vacuum) e) Mutual antagonism among those states f) Adequate military resources (or a military or technological advantage) 2. States succeed in empire building if they have an ideology that promotes personal identification with the state, empire, leader, conquest, and/or militarism 3. Characteristics of well-run empires a) Build roads and transportation systems, canals, ports, etc. b) Trade increases c) Cosmopolitan cities—art and education flourish d) Effective bureaucracy to ensure communication, collect taxes, oversee coinage, ensure the emperor’s laws are enforced e) Common official language (communication) f) System of justice, law for entire empire g) Citizenship or rights extend in some degree to conquered; must be some buy-in 4. Major results of empire: a) Economic rewards, especially in the early years, redistributed to elite and trickles down to other classes (esp. merchants, scribes, etc.) b) Relative stability and prosperity c) Population increase 5. Empires fall because: a) Failure or leadership; focus on wealth, etc. not the needs of the state b) Ideology of expansion and conquest leads to attempting new conquests beyond a practical limit: overstretching of bureaucracy, military, resources, communications c) Lack of new conquests erodes economic base and lessens faith in ideology that supported the empire d) Rebellions from within/ challenges from without