* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Text - ACT on Alzheimer`s

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

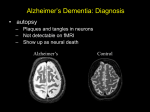

Running head: EFFECTIVE INTERACTIONS 1 ACT on Alzheimer’s Alzheimer’s Disease Curriculum Module IV - Effective Interactions GUIDELINES AND RESTRICTIONS ON USE OF DEMENTIA CURRICULUM MODULES This curriculum was created for faculty across multiple disciplines to use in existing coursework and/or to develop as a stand-alone course in dementia. Because not all module topics will be used within all disciplines, each of the ten modules can be used alone or in combination with other modules. Users may reproduce, combine, and/or customize any module text and accompanying slides to meet their course needs. Use restriction: The ACT on Alzheimer's®-developed dementia curriculum cannot be sold in its original form or in a modified/adapted form. NOTE: Recognizing that not all modules will be used with all potential audiences, there is some duplication across the modules to ensure that key information is fully represented (e.g., the screening module appears in total within the diagnosis module because the diagnosis module will not be used for all audiences). © 2016 7/2016 EFFECTIVE INTERACTIONS 2 Acknowledgement We gratefully acknowledge the funding organizations that made this curriculum development possible: the Alzheimer’s Association MN/ND and the Minnesota Area Geriatric Education Center (MAGEC), which is housed in the University of MN School of Public Health and is funded by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA). We specifically acknowledge the principal drafters of one or more curriculum modules, including Mike Rosenbloom, MD; Olivia Mastry, MPH, JD; Gregg Colburn, MBA; and the Alzheimer’s Association. In addition, we would like to thank the following contributors and peer review team: Michelle Barclay, MA Terry Barclay, PhD Marsha Berry, MA, CAEd Erin Hussey, DPT, MS, NCS Sue Field, DNP, RN, CNE Julie Fields, PhD, LP Jane Foote EdD, MSN, RN Helen Kivnik, PhD Kenndy Lewis, MS Riley McCarten, MD Teresa McCarthy, MD, MS Lynne Morishita, GNP, MSN Becky Olson-Kellogg, PT, DPT, GCS Jim Pacala, MD, MS Patricia Schaber, PhD, OTR/L John Selstad Ericka Tung, MD, MPH Jean Wyman, PhD., RN, GNP-BC, FAAN, FGSA This project is/was supported by funds from the Bureau of Health Professions (BHPr), Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) under Grant Number UB4HP19196 to the Minnesota Area Geriatric Education Center (MAGEC) for $2,192,192 (7/1/2010—6/30/2015). This information or content and conclusions are those of the author and should not be construed as the official position or policy of, nor should any endorsements be inferred by the BHPr, HRSA, DHHS or the U.S. Government. Minnesota Area Geriatric Education Center (MAGEC) Grant #UB4HP19196 Director: Robert L. Kane, MD Associate Director: Patricia A. Schommer, MA 7/2016 EFFECTIVE INTERACTIONS Overview of Alzheimer’s Disease Curriculum This is a module within the Dementia Curriculum developed by ACT on Alzheimer’s. ACT on Alzheimer’s is a statewide, volunteer-driven collaboration seeking large-scale social change and community capacity-building to transform Minnesota’s response to Alzheimer’s disease. An overarching focus is health care practice change to ensure quality dementia care for all. All of the dementia curriculum modules can be found online at www.ACTonALZ.org. Module I: Disease Description Module II: Demographics Module III: Societal Impact Module IV: Effective Interactions Module V: Cognitive Assessment and the Value of Early Detection Module VI: Screening Module VII: Disease Diagnosis Module VIII: Dementia as an Organizing Principle of Care Module IX: Quality Interventions Module X: Caregiver Support Module XI: Alzheimer’s Disease Research Module XII: Glossary 7/2016 3 EFFECTIVE INTERACTIONS ACT on Alzheimer's has developed a number of practice tools and resources to assist providers in their work with patients and clients who have memory concerns and to support their care partners. Among these tools are a protocol practice tool for cognitive impairment, a decision support tool for dementia care, a protocol practice tool for mid- to late-stage dementia, care coordination practice tools, and tips and action steps to share with a person diagnosed with Alzheimer's. These best practice tools incorporate the expertise of multiple community stakeholders, including clinical and community-based service providers: • • • • • • Clinical Provider Practice Tool Electronic Medical Record (EMR) Decision Support Tool Managing Dementia Across the Continuum Care Coordination Practice Tool Community Based Service Provider Practice Tool After A Diagnosis While the recommended practices in these tools are not location-specific, many of the resources referenced are specific to Minnesota. The resource sections can be adapted to reflect resources specific to your geographic area. To access ACT practice tools and resources, as well as video tutorials on screening, assessment, diagnosis, and care coordination, visit: http://actonalz.org/provider-practice-tools 7/2016 4 EFFECTIVE INTERACTIONS 5 Module IV: Learning Objectives Upon completion of this module the student should: • Understand the principle of person-centered care and the importance of recognizing each person as a unique individual. • Articulate verbal and non-verbal communication that people with cognitive impairment may display. • Reframe what is traditionally labeled difficult behaviors to expressions of needs, desires, and distress and understand how those expressions are manifested in specific behaviors. Module IV Effective Interactions Case Study: Mr. Johnson, a 71 year-old man with a history of diabetes who currently lives alone, is brought into the clinic by his son, Dave. Mr. Johnson does not believe he has any significant memory problems, yet Dave describes 2.5 years of progressive memory deficits characterized by increasing late fees while paying bills and difficulty maintaining the household. Over the past three months, Dave has received repeated phone calls from his father in which he complains repeatedly about losing items around the household. At one point, he wondered whether somebody was stealing his keys and reading glasses. Originally, Dave suspected that his father was fixated on this topic but, over time, it became clear that he had forgotten about the original conversations. His cognitive review of systems is remarkable for forgetting appointments and becoming lost while driving in familiar neighborhoods. Dave mentions that he is worried about his dad’s driving as well. He denied any specific symptoms for depression. The past medical history includes diabetes and hypertension. He was previously on a more complicated medication regimen aiming for “tighter” blood sugar control. He is now taking metformin, which is taken two times a day, and lisinopril, and a baby aspirin, which can be taken once a day. He will occasionally take Tylenol PM (with diphenhydramine) at night for sleep. The primary provider is hoping that simplifying the medication regimen will make it easier for Mr. Johnson to follow instructions accurately. Mr. Johnson is a retired janitor with a high school education. No active smoking or drinking. There is a family history of Alzheimer’s disease in his father who developed symptoms at age 81. 7/2016 EFFECTIVE INTERACTIONS 6 Neurological exam was non focal. Neuropsychological screening showed a MoCA=21 (losing points for cube copy, 1/5 words after 5 minutes [could not recognize when given a list], orientation to date, clock draw). Laboratory studies showed normal complete blood count, electrolytes, LFTs, glucose, thyroid stimulating hormone, and B12 levels. A referral was made for neuropsychological testing: Mr. Johnson showed severe deficits in learning and memory, moderate deficits in visuospatial function, and mild executive impairments. The Geriatric Depression Scale score was 2 and within normal limits. Brain MRI was positive for bilateral hippocampal and parietal atrophy, but no evidence for stroke or focal lesions. Mr. Johnson was diagnosed by his primary provider with probable Alzheimer’s disease. Dave inquired about any interventions that can possibly slow or treat the disease process. It is clear that Dave is distressed about his father’s new diagnosis. He has many questions about his father’s safety and how he can proactively take steps to ensure his dad’s well being. Providing care for a person with dementia presents its own set of unique challenges. At the core of effective care is honoring the humanity of the person dealing with dementia. This module also provides suggestions for effective communication, appropriate physical interaction, and assessment and understanding of behaviors exhibited by an individual with dementia. Dementia Care Overview Before addressing specific suggestions, there are basic understandings that are important for formal and informal caregivers to consider. First, it is critical to acknowledge that the individual with dementia is a human being and one must respect that person’s humanity. Second, the changes in this person are the result of a disease in the brain over which the individual has no control. Last, the person may exhibit strange or difficult behaviors, which are best viewed as expressions of needs, desires, and distress. This is especially true when traditional modes of communication are no longer viable. This module includes tips and suggestions for positive interactions with persons with dementia. Three core principles guide interactions with person with dementia. First, always affirm the person’s feelings and show empathy. This advice can be applied in many caregiving settings and is very important in dementia care. Second, bring curiosity to challenging situations and solve problems whenever possible. A lack of problem identification and resolution can lead to anxiety for people with dementia. Third, if other strategies are not working, examine one’s own actions and, if needed, distract the individual, and/or relocate him/her in order to shift the circumstances that may be creating the problem (Alzheimer’s Association, 2011). A model for caregivers to consider is person-centered care. The idea behind person-centered care is that each person is unique and the care of that person should be tailored to the unique personal attributes of that individual. This tailored care can be more challenging in a person with dementia 7/2016 EFFECTIVE INTERACTIONS 7 because it may be more difficult for the caregiver to interpret what characteristics are core to the person’s personality and what the underlying needs and desires may be (Spencer, et al.), (Michigan Dementia Coalition, 2006). To provide person-centered care, a caregiver needs to understand the following personal characteristics of the individual. The questions include (Spencer, Robinson & Curtin): What makes this person unique? What is his or her personality? What core qualities define this person? Once the caregiver answers these questions, s/he may develop care that is more appropriate for this individual. For example, if the individual has a great love for music and the arts, it would be appropriate to include these passions into the care plan for this individual. The Michigan Dementia Coalition (2006) states, “Providing person-centered care means taking the time and making the effort needed to know the person as an individual so that her unique individuality is honored” (p. 8). As one begins the process of gathering individual-specific information, one can consider the following sources. One can interview staff members who have worked with the individual in the past. One can develop a family questionnaire that provides details on the person’s life as well as family stories that might be relevant. A caregiver can also utilize photographs or biographical information to better understand details about the individual’s life. Effective Communication Effective communication with a person with dementia can be a challenge for family members and caregivers. To complicate matters, the individual’s communication patterns may change as the disease progresses. Caregivers need to be aware of these changing communication patterns and adjust their own communication methods to meet the needs of individuals. Regardless of the stage of the disease, developing a healthy and productive relationship with an individual will greatly enhance one’s ability to effectively communicate with a person with dementia (Spencer, Robinson & Curtin). The following is a list of communication challenges faced by individuals with dementia. The intensity of these challenges will vary by individual and the stage of the disease. Frequent communication challenges may include (Alzheimer’s Association, 2011): Difficulty in finding or remembering words Repetition Loss of reading or writing ability Reversion to a native language Loss of ability to speak in clear sentences 7/2016 EFFECTIVE INTERACTIONS Loss of ability to understand oral communication Inability to use words effectively In response to the communication challenges listed above, a family member or caregiver should keep the following communications guidelines in mind. Utilizing these tips may enable a caregiver to improve his/her communication with an individual which will allow for improved and more personalized care (Robinson et al., 2007): Eliminate potential distractions when speaking with a person with dementia (no TV, music, etc.); Provide orienting information at the beginning of a conversation (name, relationship, etc.); Look directly at the person when speaking and ensure that you have the person’s attention; Position oneself at eye level with the individual; Speak clearly and slowly; Use short, simple sentences; Ask simple yes/no or either/or type questions; Use concrete terms and familiar words; Talk in an easy-going, pleasant manner; Allow sufficient time for the person to respond; and/or When discussing tasks, break the task up into smaller, easier steps. There will be times when the tips listed above will be utilized, but the person with dementia is still not understanding or being understood. This can be a difficult and frustrating situation. While there is no cure-all, the following suggestions may help (Robinson et al., 2007): Be sure that you are allowing sufficient time for the individual to process what you are saying and to respond. Demonstrate visually (using non-verbal communication) what you are trying to say. Think about the complexity of what you are saying and rephrase in a more simplistic manner if possible. If all else fails, give the person a reassurance cue such as a hug, pat on the knee or back, and then change the subject. Another communication challenge for a caregiver is the inability to understand what the individual is expressing. This is a particularly difficult circumstance because it can lead to frustration for the individual. The following are suggestions to help the caregiver manage this situation (Robinson et al., 2007): Listen actively and carefully; Try to focus on a word or phrase that makes sense; 7/2016 8 EFFECTIVE INTERACTIONS 9 Respond to the emotional, or non-verbal, tone of the statement; Always stay calm; and/or Ask family members about possible meanings of what is being said. Regardless of what challenges a caregiver faces, there are certain actions that should always be avoided. The following list will hopefully help the caregiver avoid a negative interaction with an individual (Robinson et al., 2007): Don’t argue with the person. Don’t order the person around. Don’t tell people what they can’t do. Don’t be condescending. Don’t ask lots of questions that rely on good memory. Don’t talk about people in front of them. Lastly, there are other forms of communication besides verbal communication. It is important for a caregiver to consider other forms of communication, particularly when verbal communication has not produced the desired results. The following is a list of suggestions when verbal communication fails (Robinson et al., 2007): Try distracting the person. Ignore a verbal outburst if you can’t think of a positive response. Try other non-verbal forms of communication. Learn your own body language and identify whether it is triggering negative responses. Learn the body language of the other person to better understand his/her needs and desires. Physical Interaction As outlined above, developing a meaningful and trusting relationship is critical to effective care for persons with dementia. One important element of developing that relationship is to determine how to approach the individual physically in a way that does not create anxiety. All of the communication skills discussed earlier can be far less effective if the individual has become scared or anxious based on the physical approach of the caregiver. The following is a list of actions for a positive physical approach (Alzheimer’s Association, 2011): Approach the individual from the front so that he/she can see you coming. Move slowly; a rapid approach might alarm the individual. Once you have approached the individual, assume a position at the individual’s side. Position yourself at the same level as the individual; talking down to an individual can be intimidating. Offer your hand with your palm facing up, this is a non-threatening motion. Use the person’s preferred name. 7/2016 EFFECTIVE INTERACTIONS 10 Wait for a response before moving into a conversation or into direct care. Reframing, Assessing, and Managing Actions A person with dementia may exhibit many actions that may cause concern for family members and caregivers which can include (Alzheimer’s Association, 2011): Wandering Exiting or trying to leave Wanting to go home Showing fatigue as the day progresses Sleep disturbances Looking or searching for things Gathering or hoarding Expressing discomfort Having hallucinations or delusions Being suspicious or paranoid Repetitive actions Loud verbalizations that may not be coherent A unique but effective approach to view and address a person’s actions is to reframe the actions not as “problem behaviors to manage,” but as expressions or communications of needs, desires, or distress. Reframing in this manner allows one to be curious and observe a person’s actions to discover the root cause of a person’s actions. An individual may be unable to communicate frustration verbally, so he/she may resort to other means of expression. For example, a new home, a new room, furniture changes, temperature changes, and changes in lighting could all trigger expressions of need, desires, or distress. Past behavior patterns of an individual or a new task or an unpopular task may trigger expressions or communication of need, desires, or distress (Spencer, Robinson & Curtin). Reframing may enable a caregiver to respond more productively to that behavior in the future. For example, one might view wandering as a demonstration of mobility rather than simply aimless movement. Hoarding, a common behavior among person with dementias, could instead be viewed as shopping, a daily activity of life (Alzheimer’s Association, 2011). Reframing also allows for opportunities to explore new approaches to meeting needs. There are times when certain expressions, communications, or acts become a problem for the caregiver, the individual, or other people living in proximity to the individual. A caregiver needs to understand when a behavior has crossed the line and needs to be addressed or modified. If an action violates the rights of others, then caregivers must intervene. The individual may not be able to properly assess their own actions, so it is important for the caregiver to provide such oversight. A second circumstance that should lead to intervention is if the health of the 7/2016 EFFECTIVE INTERACTIONS 11 individual, or someone else, is at risk as a result of a certain action (Alzheimer’s Association, 2011). Research has also developed strategies for addressing actions, expressions, and communication often seen in persons with Alzheimer’s disease. Guerriero, et al., (2004) provides protocols to manage the common actions associated with Alzheimer’s disease. The integration of behavioral interventions and primary care has been successful. The behavioral disturbances addressed by Guerriero are: Depression/anxiety Aggression/agitation Repetitive behavior Delusions and hallucinations Managing personal care Mobility Sleep disturbances Brauner, Muir, and Sachs (2000) address the common challenge of providing primary care for individuals with Alzheimer’s disease. Traditional primary care management techniques may not apply to individuals with Alzheimer’s disease. As a result, the primary care provider needs to consider the cognitive abilities of the person with dementia as well as the common actions demonstrated by people with Alzheimer’s disease before suggesting primary care treatment. Even basic concerns of adherence to therapy need to be addressed; “Any time clinicians consider adding a new drug or performing a procedure for an individual with dementia, they need to appreciate the potential difficulties individuals may have in correctly following instructions” (Brauner, 2000, p. 3231). Brauner, Muir, and Sachs (2000) summarize that primary care treatment decisions need to consider all of the following factors: decision-making capacity of the individual, altered benefits and burdens of treatment, the ability of the individual to adhere to a treatment regimen, the ability of caregivers, and mechanisms to compensate for communication and other deficits. ACT on Alzheimer’s Tools: Tool for coordinating overall care and supporting behavioral expressions are available to assist providers and care coordination. See http://www.actonalz.org/provider-practice-tools Case Study Continued: Pharmacological Intervention: Mr. Johnson is started on Donepezil 5 mg daily for 1 month, increasing to 10 mg daily thereafter. The primary provider explains that this medication only provides symptomatic treatment and does not slow the disease process. It is recommended that 7/2016 EFFECTIVE INTERACTIONS 12 the patient avoid taking Tylenol PM due to the diphenhydramine’s anticholinergic effects, and he is prescribed trazodone 50 mg at night for insomnia. Since the patient had no evidence for depression by history and score on the Geriatric Depression Scale, there is no role for an antidepressant. Non-Pharmacological Intervention The primary provider has a Family Meeting where he counsels Mr. Johnson and Dave about healthy lifestyle, safety concerns, maximizing his function, socialization, and ongoing education and support of Mr. Johnson and Dave, his care partner. This is the first time that Dave realizes that he is a “care partner.” Physical activity is the priority, given Mr. Johnson’s diabetes and literature supporting favorable impact of this intervention upon cognition. The patient was recommended to use his home exercise bike for 30 minutes at a time for 3 days weekly. After discussing options for increasing cognitive activity, the patient decides to meet friends to play cards at the senior center twice a week in addition to daily reading. He is also enrolled in a Brain & Body Wellness Program. He is provided a calendar to write down his appointments and activities. At the Brain and Body Wellness program, the health educators stress the importance of a daily routine. The primary provider has numerous safety concerns about Mr. Johnson’s living situation. In the setting of newly diagnosed Alzheimer’s disease, Mr. Johnson has an increased risk for mediation non-adherence. The primary provider recommends that he utilize a pillbox with daily reminders from his son. Dave feels he is able to visit his father once a week and set up two pillboxes indicating the days of the week, one marked “morning” and one marked “evening”; when he makes reminder calls, he can tell his father to take the pills from the appropriate box and indicate the day of the week so that the correct medications are taken. When Dave calls to remind Mr. Johnson about his medication, he will also review the day’s activities with him and write them on a white board on the back of his front door. Mr. Johnson and his son get along well. The primary provider discusses the importance of the care partner; Dave will accompany his father to follow-up appointments so that he will also hear the treatment plan, when the next appointment should be, and symptoms and signs to look for that would indicate a need for a more urgent visit. A home care nurse is arranged to go to the home to assess Mr. Johnson’s home situation for safety, assess if he is able to follow phone instructions from his son accurately, ensure that he is eating regularly, and ensure adequate housekeeping. 7/2016 EFFECTIVE INTERACTIONS 13 Mr. Johnson and Dave decide that it might be a good idea to try putting a small table by the front door where he can leave his keys and a stand up glasses case can be placed next to his favorite reading chair. They will put a white board on the back of the front door indicating where the keys and reading glasses might be. If this doesn’t work, they will try another plan. In addition, it is suggested that Dave and his father discuss the possibility of Dave obtaining power of attorney and beginning to manage the patient’s finances. All bills are subsequently placed on autopay. Mr. Johnson has been responsible for his own meals. There have been no problems thus far with forgetting to shut off stove burners. The family is counseled about other options that include prepared meals and microwave meals as well as Meals on Wheels. Mr. Johnson’s primary provider shares Dave’s concerns about Mr. Johnson’s driving safety. Due to symptoms of disorientation in familiar places, the primary provider recommends a formal driving evaluation through occupational therapy. Mr. Johnson is instructed not to drive until this evaluation has been completed. Dave sets up transportation to and from the Senior Center for the card game sessions. They will find out if this senior center has meals, and if so, he may eat a warm lunch with his friends on card game days. The primary provider makes a referral to the Alzheimer’s Association to provide additional education regarding Alzheimer’s disease and information relating to community resources. Mr. Johnson and Dave begin care consultation to learn about the disease, what they might expect as a course of progression, and how to prepare to manage at later stages of the disease. The primary provider sees Mr. Johnson and Dave in follow-up appointments to see how they are coping at home with the new diagnosis. He is tolerating the donepezil without difficulty and adjusting well to his new schedule. His primary provider uses the opportunity to discuss Mr. Johnson’s overall healthcare goals, hopes, and fears about the future. Mr. Johnson would like both of his sons to be his joint health care proxies. He mentions his fears about losing his independence and goal of staying in his own home as long as possible. Given this information, they discuss the importance of identifying a health care proxy and writing an advance directive. They make a plan to see each other in three months for follow-up. 7/2016 EFFECTIVE INTERACTIONS 14 Module IV: Questions for Review 1. Behaviors associated with Alzheimer’s disease are most effectively managed with medication therapy. T/F 2. Disruptive behavior in patients with Alzheimer’s disease is best interpreted as: A. A deliberate attempt to upset caregivers B. Anger about the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s dementia C. An attempt to communicate D. A mechanism to control the environment 3. Effective interactions with an Alzheimer’s patient are facilitated by A. Speaking loudly B. Recognizing the person as a unique individual C. Avoiding physical contact D. Giving detailed instructions about what you want the patient to do 4. Mrs. L is a 75-year-old woman living in a dementia care AL because she is no longer able to perform her IADLs without help. She is often irritable with the staff and threatens to “call the police” when they attempt to help her shower. She can become physically aggressive especially with male caregivers. When staff ask her why she is upset she consistently replies “none of your damn business”. To provide the most effective care to this patient, the AL staff should first: A. Insist Mrs. L take a shower or bath at least weekly B. Provide only female aides to help Mrs. L in the shower C. Avoid showers in this resident as it is too upsetting 7/2016 EFFECTIVE INTERACTIONS 15 D. Review Mrs. L’s life history with family/friends to determine if there is a reason why she is fearful of the shower and particularly male caregivers 5. Breakfast in the large dining room of the nursing home is interrupted when Mr. B accidentally knocks his plate off the table and it breaks on the floor. 3 staff members quickly move to his side, pull his wheelchair out to clean up the mess, and have a discussion about how frequently “he” needs more supervision at meals. Mr. B begins to shout loudly and shake his fist. He strikes out at the person seated next to him and needs to be removed from the dining room without finishing breakfast. What mistake did staff make in managing this care situation? A. Not demonstrating empathy B. Rapidly approaching him C. Discussing his “faults” in his presence D. All the above. 6. The Unites States is training adequate number of professional health care workers to take care of the growing aging population T/F 7/2016 EFFECTIVE INTERACTIONS 16 References Alzheimer’s Association. (2011). Understanding memory loss: A personal and public Imperative. Brauner, D.J., Muir, J.C., Sachs, G.A. (2000).Treating nondementia illnesses in Individuals with dementia. JAMA, 283, 3230-3235. Guerriero Austrom, M., Damush, T.M., Hartwell, C.W., Perkins, T., Unverzagt, F., Boustani, M., Hendrie, H.C., & Callahan, C.M., (2004). Development and implementation of Nonpharmacologic protocols for the management of individuals with Alzheimer's disease and their families in a multiracial primary care setting. Gerontologist. 44(4), 548-553. Michigan Dementia Coalition. (2006). Knowledge and skills needed for dementia care. Robinson, A., Spencer, B., & White, L. (2007). Understanding Difficult Behaviors: Some Practical Suggestions for Coping With Alzheimer's Disease and Related Illnesses. Ypsilanti, Michigan: Eastern Michigan University. Spencer, B., Robinson, A., & Curtin, C. (n.d.). Developing Meaningful Connections with People with Dementia: A Training Manual. Retrieved from http://www.dementiacoalition.org/resources/ 7/2016