* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download 25. HIV and Pulmonary Diseases

Survey

Document related concepts

Neonatal infection wikipedia , lookup

Hygiene hypothesis wikipedia , lookup

Globalization and disease wikipedia , lookup

Management of multiple sclerosis wikipedia , lookup

Sjögren syndrome wikipedia , lookup

Infection control wikipedia , lookup

Transcript

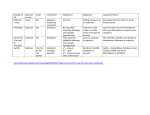

References and Internet addresses 639 25. HIV and Pulmonary Diseases Sven Philip Aries, Bernhard Schaaf The spectrum of lung diseases in HIV-infected patients encompasses complications typical for HIV such as tuberculosis, bacterial pneumonia, lymphomas and HIVassociated pulmonary hypertension, but also includes typical everyday pulmonary problems like acute bronchitis, asthma, COPD and bronchial carcinomas (Table 1). Classical diseases such as PCP have become rarer as a result of HAART and chemoprophylaxis, so that other complications are on the increase (Grubb 2006). None other than acute bronchitis is the most common cause of pulmonary problems in HIV patients (Wallace 1997). However, particularly in patients with advanced immune deficiency, it is vital to take all differential diagnoses into consideration. Anamnestic and clinical appearance are often essential clues when it comes to telling the difference between the banal and the dangerous. Table 1: Pulmonary complications in patients with an HIV infection Infections Neoplasia Other Pneumocystis jiroveci Kaposi sarcoma Lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia Bacterial pneumonia S. pneumoniae S. aureus H. influenzae B. catarrhalis P. aeruginosa Rhodococcus equi Nocardia asteroides Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma Hodgkin’s lymphoma Non-specific interstitial pneumonia Bronchial carcinoma Pulmonary hypertension COPD Bronchial hyperreactivity Mycobacteria M. tuberculosis Atypical mycobacteria Other Cytomegalovirus Aspergillus spp. Cryptococcus neoform. Histoplasma capsulatum Toxoplasma gondii This chapter presents an outline of differential diagnoses in patients with respiratory complaints. PCP, mycobacterioses and pulmonary hypertension are covered in detail in chapters elsewhere. 640 HIV and Pulmonary Diseases Anamnesis What are the previous illnesses of the patient? Someone who has suffered from a PCP once is at a higher risk of having another one. A patient with hyperlipidaemia and carotid stenosis might have coronary heart disease. What medication does the patient take? Taking cotrimoxazol regularly makes a PCP unlikely, and the risk of bacterial pneumonia may also be reduced (Beck 2001). In the case of PCP prophylaxis with Pentamidine inhalation, however, atypical, often apically pronounced manifestations of a PCP are to be expected. Has the patient recently started HAART? Particularly HAART can induce pulmonary problems: During a newly begun course of treatment with abacavir, asthma could also be due to hypersensitivity. Dyspnea (13 %), cough (27 %) and pharyngitis (13 %) are common symptoms (Keiser 2003). Some patients even develop pulmonary infiltrates. T-20 seems to increase the risk of bacterial pneumonia, at least among smokers. Dyspnea and tachypnea are also seen in lactic acidosis secondary to nuke therapy. In addition, pulmonary symptoms after institution of HAART might result from the Immune Reconstitution and Inflammatory Syndrome (IRIS). The list of etiologies includes a number of infective and non-infective causes (Grubb 2006). Low CD4+ T-cell count and high viral load are risk factors. In a retrospective analysis, IRIS was seen in 30 % of patients with TB, atypical mycobacteriosis and cryptococcosis (Shelburn 2005). Does the patient smoke? Although smoking is more harmful to HIV-positive than to HIV-negative persons, it is still more common among HIV-positives (Royce 1990). All HIV-associated and HIV-independent pulmonary diseases are more common in smokers than in non-smokers. This starts with bacterial pneumonia and PCP, but also applies to asthma, COPD and pulmonary carcinomas (Hirschtick 1996). Smoking promotes the formation of a local immune deficit in the pulmonary compartment: it reduces the number of alveolar CD4+ cells and the production of important proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1 and TNF-α (Wewers 1998). Furthermore, smoking suppresses the phagocytosis capacity of alveolar macrophages. This effect is more pronounced in HIV patients than in HIV-negative patients. HIV infection itself, however, does not seem to have any direct influence on the capability for bacterial killing (Elssner 2004). Motivating the patient to restrict nicotine intake is thus an important medical task, particularly in HIV consultation. Strategies which promise success and are supported by the evidence of studies include participation in motivational groups, nicotine substitutes and taking Buproprion, whereby interactions, particularly with Ritonavir, should be taken into consideration. Anamnesis 641 Where does the patient come from? Another important question is that of the travelling history and/or the origin of the patient. There are places where disease such as histoplasmosis and coccidiomycosis occur endemically. Histoplasmosis, for example, is more widespread in certain parts of the USA and in Puerto Rico than PCP, while it is rare in Europe. Tuberculosis plays a greater role among immigrants. How did the patient become infected with HIV? Intravenous drug users suffer more often from bacterial pneumonia or tuberculosis (Hirschtick 1995). Pulmonary Kaposi’s sarcomas are almost exclusively found in MSM (men who have sex with men). What are the symptoms? Occasionally, some valuable information can be gained above the more uniform symptoms such as coughing and shortness of breath, which might be useful for differentiation between PCP and bacterial pneumonia. Thus, for example, it is typical for the onset of bacterial pneumonia to be more acute. Patients usually go to the doctor after only 3-5 days of discomfort, whereas patients with PCP suffer from symptoms for an average of 28 days (Kovasc 1984). PCP patients typically have dyspnea and a non-productive cough. A large quantity of discoloured sputum is more likely to indicate a bacterial cause or a combination of infections. What does the chest X-ray look like? Table 2: Chest X-ray findings and differential diagnosis Chest X-ray Typical differential diagnosis Without pathological findings Focal infiltrates Multifocal infiltrates Diffuse infiltrates PCP, asthma, KS of the trachea Bacterial pneumonia, mycobateriosis, lymphoma, fungi Bacterial pneumonia, mycobacteriosis, PCP, KS PCP (centrally pronounced), CMV, KS, LIP, cardiac insufficiency, fungi Mycobacteriosis, fungi PCP Mycobacteriosis (CD4 > 200), bacterial abcess (Staph., Pseudomonas) PCP, fungi Bacterial pneumonia, mycobacteriosis, KS, lymphoma, cardiac insufficiency Mycobacteriosis, KS, sarcoidosis Miliary image Pneumothorax Cavernous lesions Cystic lesions Pleural effusion Bihilar lymphadenopathy The most important question: What is the immune status? The number of CD4+ T-cells provides an excellent indication of the individual risk of a patient to suffer from specific opportunistic infections. More important than the nadir is the current CD4+ T-cell count. In patients with more than 200/µl, infection with typical opportunistic HIV-associated diseases is very unlikely. Here, as with HIV-negative patients, one generally tends to expect more „normal“ problems like acute bronchitis and bacterial pneumonia. However, tuberculosis should always be considered. Although the risk of becoming infected with tuberculosis grows along 642 HIV and Pulmonary Diseases with increasing immunodeficiency, more than half of all tuberculosis infections in HIV patients occur at a CD4+ T-cell count of above 200/µl (Lange 2004, Wood 2000). At less than 200 CD4+ T-cells/µl, PCP and, more rarely, pneumonia/pneumonitis with cryptococci, occurs. At this stage too, however, bacterial pneumonia is the most common pulmonary disease overall. Below 100 CD4+ T-cells/µl, there is an increase in the number of pulmonary Kaposi sarcomas and toxoplasma gondii infections. At a cell count of under 50/µl, infections with endemic fungi (histoplasma capsulatum, Coccidioides immitis), non-endemic fungi (Aspergillus, Candida species), atypical mycobacteria and different viruses (mostly CMV) occur. Especially in patients with advanced immunodeficiency, it must be remembered that pulmonary illness may only represent an organ manifestation of a systemic infection. Rapid, invasive diagnostic procedure is thus advisable in such patients. Pulmonary complications Bacterial pneumonia Bacterial pneumonia occurs more often in HIV-positive than in HIV-negative patients, and, like PCP, leaves scars in the lung. This often results in a restriction of pulmonary function which goes on for years (Alison 2000). Although bacterial pneumonia occurs in the early stages of HIV infection, the risk grows along with increasing immunosuppression. A case of bacterial pneumonia significantly worsens the long-term prognosis of the patient (Osmond 1999). Thus, contracting bacterial pneumonia more than once a year is regarded as AIDS defining. The introduction of HAART went hand in hand with a significant reduction in the occurrence of bacterial pneumonia (Jeffrey 2000). Clinically and prognostically speaking, there is no great difference between bacterial pneumonia in HIV-infected patients and pneumonia in an immunocompetent host. However, the HIV-patient more often presents with less symptoms and a normal leucocyte count (Feldman 1999). Etiologically, pneumococci and haemophilus infections are most common. In comparison with immunocompetent patients, infections with Staphylococcus aureus, Branhamella catarrhalis, and in the later stages (< 100 CD4+ T-cells/µl) Pseudomonas spp. occur more often. In the case of slow-growing, cavitating infiltrates, there is also the possibility of rare pathogens such as Rhodococcus equi and nocardiosis. Polymicrobial infections and co-infections with Pneumocystis jiroveci are common (10-30 %), which makes clinical assessment difficult (Miller 1994). What is also important for the risk stratification of the patient, in addition to the usual criteria (pO2, extent of infiltrate, effusion, circulatory condition, extrapulmonary involvement and confusion of the patient) is the CD4+ T-cell count. The mortality of patients with < 100 cells/µl is increased more than sixfold. Therefore it probably makes sense when dealing with patients with a pronounced immune defect not to rely on the risk scores validated for immunocompetent patients and to admit apparently less severely ill patients to the hospital for treatment (Cordero 2000). Pulmonary complications 643 Should there be no suspicion of mycobacteriosis, a calculated antibacterial treament of patients with a CD4+ T-cell count of > 200/µl with medication effective against S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae und S. aureus is indicated. However, there are no controlled studies available to support this. In accordance with recommended therapies for community acquired pneumonia with co-morbidity, the prescription of a Group 2 Cephalosporin such as Cefuroxim or group 3a such as Cefotaxim/Ceftriaxon, or an aminopenicillin with betalactamase inhibitor (Ampicillin/Sulbactam or Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, e.g. Augmentan™ 875/125 mg, twice daily) can be recommended. In the case of regionally increased incidence of legionella infection, combination with a macrolide is advisable (e.g. Klacid™ 500 mg twice daily). Once positive culture results have been obtained, the patient should receive further specific treatment. With advanced immunodeficiency (CD4+ T-cells < 200/µl), primary consideration should be given to bronchoscopic diagnostics, due to the broader spectrum of pathogens (Dalhoff 2002). In patients with a high risk of pseudomonas infection (low CD4 count, nosocomial infection, sepsis) initial therapy should include antibiotics active against pseudomonas. Pneumococcus vaccination is recommended. At a CD4+ T-cell count lower than 200/µl, however, there is no proof of vaccination benefit. Due to the frequency of secondary bacterial infections, an annual influenza vaccination is also advisable. Which diagnostic strategy makes sense with pulmonary infiltrates? The intensity of the diagnostic workup in a patient with pulmonary infiltrates is based on the HIV stage and the expected spectrum of pathogens. With a CD4+ Tcell count of > 200/µl, non-invasive basic diagnostics and a calculated antibiotic therapy are justified. This basic diagnostic investigation includes taking two blood cultures and a microscopic and cultural sputum examination. The bacteremia rate seems to be higher than in immunocompetent patients (Miller 1994). The main value of sputum culture is the demarcation of mycobacterial and aspergillus infections. In individual cases the possibility of antigen detection in the urine should be considered (e.g. pneumococcus, legionella. cryptococcus, histoplasma). The determination of the cryptococcus antigen in serum has a high predictive value for the detection of invasive cyptococcosis (Saag 2000). A chest CT is sometimes helpful in the diagnostic workup (high-resolution CT, HR-CT). A PCP, for example, might be depicted in an HR-CT, but might be missed in a conventional chest X-ray. In advanced stages (< 200 CD4+ T-cells/µl), bronchoscopic investigation is primarily recommended (Dalhoff 2002). The diagnostic success rate of a bronchoscopy in HIV-infected patients with pulmonary infiltrates is 55-70 % and rises to 8990 % when all techniques including the transbronchial biopsy are combined (Cadranel 1995). The sensitivity of a bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) amounts to 60-70 % in bacterial pneumonia (patients without previous antibiotic treatment), and 85-100 % in PCP (Baughman 1994). Due to the high sensitivity of the BAL, transbronchial biopsy with possible complications is only recommended in the diagnosis of PCP if there is a negative initial diagnostic workup and in patients taking chemoprophylaxis (Dalhoff 2002). If invasive pulmonary aspergillosis or CMV is considered, a transbronchial biopsy should be the preferred method in order to differentiate be- 644 HIV and Pulmonary Diseases tween colonisation and tissue invasion. Surgical open biopsies and CT-controlled trans-thoracic pulmonary biopsies are rarely necessary. Asthma bronchiale One would think that an immunosuppressing disease like HIV infection would at least protect patients from manifestations of exaggerated immune reaction such as allergies and asthma. However, the opposite is the case: in a study from Canada concerning HIV-infected men, more than 50 % had suffered an episode of wheezing within the previous 12 months, and nearly half of those showed evidence of bronchial hyperreactivity. These findings were particularly distinct among smokers (Poirer 2001). As the disease progresses, it probably comes to an imbalance between too few „good“ TH1 cells producing interferon and Interleukin 2, and too many „allergy-mediating“ TH2 cells with an increased total IgE. In cases of unclear coughing, dyspnoea or recurrent bronchitis, the possibility of bronchial hyperreactivity, asthma or emphysema should be kept in mind. Emphysema Smokers with HIV infection develop pulmonary emphysema more often than noninfected smokers. It is possible that a pathogenetic synergy arises from smoking and the pulmonary infiltration with cytotoxic T-cells due to HIV infection (Diaz 2000). Smoking crack increases the risk of pulmonary emphysema even more. Here, it seems that superficial epithelial and mucosal structures are destroyed (Fliegil 1997). Furthermore, cocaine can lead to unusual manifestations with pneumothorax or alveolar infiltrates. Lymphoid interstitial pneumonia (LIP): LIP is a form of pneumonia which takes a chronic or subacute course and is extremely rare in adults. Radiologically, its reticulonodular pattern makes it similar to PCP. This illness occurs paraneoplastic, rarely, idiopathic and as in HIV and EBV disease parainfectious. In contrast to PCP, patients with LIP usually have a CD4+ T-cell count of > 200/µl and normal LDH values. A CD8-dominated lymphocytic alveolitis with no pathogen detection is characteristic. Definite diagnosis often calls for an open pulmonary biopsy. LIP is considered sensitive to steroids. The role played by HAART is unclear, especially as LIP has occasionally been observed in the context of immune reconstitution during HAART. Bronchial carcinoma HIV patients are at considerably higher risk of bronchial carcinoma. A retrospective analysis covering 8,400 patients from the years 1986-2001 showed an eightfold increased incidence of bronchial carcinoma in the period after 1996 than that for the normal smoking population. Interestingly, the majority of bronchial carcinomas are, histologically, adenocarcinomas, which results in discussion of whether HIV infection itself leads to a genetic instability (Bower 2003). Patients with bronchial carcinomas and HIV are younger, the disease is often more advanced at presentation and takes a more aggressive course than in HIV-negative patients (White 1996, Karp 1993). Whether to treat with chemotherapy, and what kind, has to be decided for References 645 each case individually. A small cohort study has shown that HIV-infected patients with advanced bronchial carcinoma have a similarly bad prognosis to that of HIV negative patients, regardless of immune status during HAART and chemotherapy (Powles 2003). Less common opportunistic infections The detection of CMV in BAL repeatedly gives rise to discussion regarding clinical relevance. Seroprevalence is high (90 %), and colonisation of the respiratory tract is common. CMV pneumonia is the primary reason for 3.5 % of pulmonary infiltrates in AIDS patients. The significance of the pathogen in the later stages may well be underestimated, since histological examination of autopsy material showed pulmonary CMV infections in up to 17 % (Afessa 1998, Waxman 1997). Regarding invasive pulmonary aspergillosis, which only occurs in the late stages and usually in conjunction with additional risk factors such as neutropenia or steroid therapy (Mylonakis 1998), please refer to the OI-Chapter. References 1. Afessa B, Green W, Chiao J, et al. Pulmonary complications of HIV infection: autopsy findings.Chest. 1998;113:1225-1229. http://amedeo.com/lit.php?id=9596298 2. Baughman R, Dohn M, Frame P. The continuing utility of bronchoalveolar lavage to diagnose opportunistic infection in AIDS patients. Am J Med 1994;97:515-522. http://amedeo.com/lit.php?id=7985710 3. Beck JM, Rosen MJ, Peavy H. Pulmonary Complications of HIV. Report of the fourth NHLBI Workshop. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001; 164: 2120-2126. http://amedeo.com/lit.php?id=11739145 4. Bower M, Powles T, Nelson M, et al. HIV-related lung cancer in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. AIDS 2003;17:371-375. http://amedeo.com/lit.php?id=12556691 5. Cadranel J, Gillet-Juvin K, Antoine M, et al. Site-directed bronchoalveolar lavage and transbronchial biopsy in HIV-infected patients with pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1995;152:1103-1106. http://amedeo.com/lit.php?id=7663791 6. Conley LJ, Bush TJ, Buchbinder SP, et al. The association between cigarette smoking and selected HIV-related medical conditions. AIDS 1996; 10:1121–1126. http://amedeo.com/lit.php?id=7651475 7. Cordero E, Pachon J, Rivero A, et al. Community-acquired bacterial pneumonia in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients: validation of severity criteria. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162:2063-8. http://amedeo.com/lit.php?id=11112115 8. Dalhoff K, Ewig S, Hoffken G, et al. Recommendations for the diagnosis, therapy and prevention of pneumonia in the immunocompromised host. Pneumologie 2002;56:807-831. http://amedeo.com/lit.php?id=12486620 9. Diaz P, King M, Pacht E, et al. Increased susceptibility to pulmonary emphysema among HIVseropositive smokers. Ann Intern Med 2000;132:369–372. http://amedeo.com/lit.php?id=10691587 10. Elssner A, Carter J, Yunger T, Wewers M. HIV-1 infection does not impair human alveolar macrophage phagocytic function unless combined with cigarette smoking. Chest 2004;125:1071-1076. http://amedeo.com/lit.php?id=15006971 11. Feldman C, Glatthaar M, Morar R, et al. Bacteremic pneumococcal pneumonia in HIV-seropositive and HIV-seronegative adults. Chest 1999;116:107-14. http://amedeo.com/lit.php?id=10424512 12. Fligiel S, Roth M, Kleerup E, et al. Tracheobronchial histopathology in habitual smokers of cocaine, marijuana, and/or tobacco. Chest 1997;112:319-326. http://amedeo.com/lit.php?id=9266864 13. Grubb JR, Moorman AC, Baker RK, Masur H. The changing spectrum of pulmonary disease in patients with HIV infection on antiretroviral therapy. AIDS 2006, 12:1095-1107. http://amedeo.com/lit.php?id=16691060 14. Hirschtick R, Glassroth J, Jordan M, et al. Bacterial pneumonia in persons infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. N Engl J Med 1995; 333:845–851. 15. Hirschtick R, Glassroth J, Jordan M, et al. Bacterial pneumonia in patients with HIV infection. N Engl J Med 1995;333:845–851. http://amedeo.com/lit.php?id=7651475 646 HIV and Pulmonary Diseases 16. Karp J, Profeta G, Marantz P, et al. Lung cancer in patients with immunodeficiency syndrome. Chest. 1993;103:410-413. http://amedeo.com/lit.php?id=8432128 17. Keiser P, Nassar N, Skiest D, et al. Comparison of symptoms of influenza A with abacavir-associated hypersensitivity reaction. Int J STD AIDS. 2003;14:478-481. http://amedeo.com/lit.php?id=12869229 18. Kovacs JA, Hiemenz JW, Macher AM, et al. Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia: A comparison between patients with the AIDS and patients with other immunodeficiencies. Ann Intern Med 1984, 100:663671. http://amedeo.com/lit.php?id=6231873 19. Lange C, Schaaf B, Dalhoff K. HIV and lung. Pneumologie 2004; 58:416-427. http://amedeo.com/lit.php?id=15216435 20. Miller R, Foley N, Kessel D, et al. Community acquired lobar pneumonia in patients with HIV infection and AIDS. 1994 Thorax; 49:367-368. http://amedeo.com/lit.php?id=8202910 21. Morris A, Huang L, Bacchetti P, et al. Permanent declines in pulmonary function following pneumonia in HIV-infected persons. Am J Resp Crit Care Med 2000, 162: 612–6. http://amedeo.com/lit.php?id=10934095 22. Mylonakis E, Barlam TF, Flanigan T, et al. Pulmonary aspergillosis and invasive disease in AIDS: review of 342 cases. Chest. 1998;114:251-262. http://amedeo.com/lit.php?id=9674477 23. Osmond D, Chin D, Glassroth J, et al. Impact of bacterial pneumonia and Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia on HIV disease progression. Clin Infect Dis 1999;29:536–543. http://amedeo.com/lit.php?id=10530443 24. Poirer C, Inhaber N, Lalonde R, et al. Prevalence of bronchial hyperresponsiveness among HIVinfected men. Am J Resp Crit Care Med 2001; 164: 542–5. http://amedeo.com/lit.php?id=11520712 25. Powles T, Thirwell C, Newsom-Davis T, et al. HIV adversely influence the outcome in advanced nonsmall-cell lung cancer in the era of HAART? Br J Cancer 2003; 89:457-459. http://amedeo.com/lit.php?id=12888811 26. Royce R, Winkelstein W Jr. HIV infection, cigarette smoking and CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts: preliminary results from the San Francisco Men's Health Study. AIDS 1990;4:327-333. http://amedeo.com/lit.php?id=1972021 27. Saag M, Graybill R, Larsen R, et al. Practice guidelines for the management of cryptococcal disease. IClin Infect Dis. 2000 30:710-718. http://amedeo.com/lit.php?id=10770733 28. Shelburne SA, Visnegarwala F, Darcourt J, et al. Incidence and risk factors for immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome during highly active antiretroviral therapy. AIDS 2005;19:399-406. http://amedeo.com/lit.php?id=15750393 29. Sullivan J, Moore R, Keruly J, et al. Effect of antiretroviral therapy on the incidence of bacterial pneumonia in patients with advanced HIV infection. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000; 162: 64–7. http://amedeo.com/lit.php?id=10903221 30. Wallace J, Hansen N, Lavange L, et al. Respiratory disease trends in the pulmonary complications of HIV Infection Study cohort. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1997;155:72-80. http://amedeo.com/lit.php?id=9001292 31. Waxman A, Goldie S, Brett-Smith H, et al. Cytomegalovirus as a primary pulmonary pathogen in AIDS. Chest 1997;111:128-134. http://amedeo.com/lit.php?id=8996006 32. Wewers M, Diaz P, Wewers M, et al. Cigarette Smoking in HIV Infection Induces a Suppressive Inflammatory Environment in the Lung. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1998;158:1543–1549. http://amedeo.com/lit.php?id=9817706 33. White DA. Pulmonary complications of HIV-associated malignancies. Clin Chest Med. 1996;17:755761. http://amedeo.com/lit.php?id=9016376 34. Wood R, Maartens G, Lombard C. Risk factors for developing tuberculosis in HIV-1-infected adults from communities with a low or very high incidence of tuberculosis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2000; 23:75-80. http://amedeo.com/lit.php?id=10708059