* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Guide to Native and Invasive Streamside Plants

Survey

Document related concepts

Habitat conservation wikipedia , lookup

Mission blue butterfly habitat conservation wikipedia , lookup

Renewable resource wikipedia , lookup

Plant defense against herbivory wikipedia , lookup

Plant breeding wikipedia , lookup

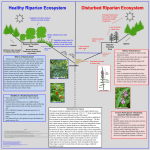

Riparian-zone restoration wikipedia , lookup

Transcript